Cranial ultrasound

| Cranial ultrasound | |

|---|---|

| Purpose | technique to scan brain |

Cranial ultrasound is a technique for scanning the brain using high-frequency sound waves. It is used almost exclusively in babies because their fontanelle (the soft spot on the skull) provides an "acoustic window". A different form of ultrasound-based brain scanning, transcranial Doppler, can be used in any age group. This uses Doppler ultrasound to assess blood flow through the major arteries in the brain, and can scan through bone. It is not usual for this technique to be referred to simply as "cranial ultrasound". Additionally, cranial ultrasound can be used for intra-operative imaging in adults undergoing neurosurgery once the skull has been opened, for example to help identify the margins of a tumour.[1]

Indications

Most neonatal units in the developed world routinely perform serial cranial ultrasound scans on babies who are born significantly premature. A typical regimen might involve performing a scan on the first, third and seventh day of a premature baby's life, and then at regular intervals until the baby reaches term.[2]

Premature babies are especially vulnerable to certain conditions involving the brain. These include intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), which often occurs during the first few days,[3] and periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), which tends to occur later on.[4] One of the main purposes of routine cranial ultrasound scanning in neonatal units is to identify these problems as they develop. If severe intraventricular haemorrhage is noted then the baby will need to be scanned more frequently in case post-haemorrhagic hydrocephalus (swelling of the ventricles as the natural flow of the cerebrospinal fluid is blocked by blood-clots) develops.

Many other conditions can also be identified by cranial ultrasound. These include:

- Subdural haemorrhage (although this is usually only visible on ultrasound if quite large)

- Abnormalities of brain development such as agenesis of the corpus callosum

- Unexpected cysts or areas of calcification, which could indicate a problem such as infection of the foetus during pregnancy.

- Brain tumours

Therefore unwell mature babies often undergo cranial ultrasound as well as premature babies.

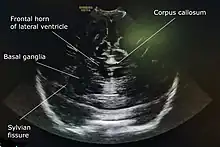

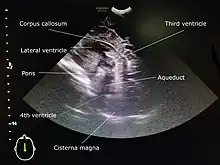

Technique

A water-based gel is applied to the infant's head, over the anterior fontanelle, to aid conduction of ultrasound waves. Ideally scans are performed during sleep or when the infant is calm. The operator then uses an ultrasound probe to examine the baby's brain, viewing the images on a computer screen and recording them as necessary.

A standard cranial ultrasound examination usually involves recording approximately 10 views of the brain from different angles, five in the coronal plane and five in the sagittal or parasaggital planes.[5] This allows all parts of the ventricles and most of the rest of the brain to be visualised.

Who performs the scans varies between different health systems. In many hospitals in the United Kingdom paediatricians or neonatologists usually perform cranial ultrasound; in other systems advanced nurse practitioners, radiologists or sonographers may perform most scans.

While the anterior fontanelle is the most commonly used acoustic window for cranial ultrasounds, more advanced operators may gain additional views, especially of posterior fossa structures, by using the mastoid fontanelle, the posterior fontanelle and/or the temporal window.[6]

Other refinements of cranial ultrasound technique include serial measurement of the width of the lateral ventricles ("ventricular index") to monitor suspected ventricular dilatation and colour Doppler to assess blood flow.

Limitations

Cranial ultrasound is a very safe technique as it is non-invasive and does not involve any kind of ionising radiation. However, it is subject to certain limitations.

- Operator dependency: the quality of images obtained relies on the skill of the person performing sonography.

- Some brain structures are poorly visualised, notably posterior fossa structures such as the cerebellum if only the anterior fontanelle is used.[7]

- If the fontanelle is very small, for example is post-mature infants, scanning may be technically difficult.

- Damage to the brain soft tissue (parenchyma), for example resulting from ischaemia or abnormal myelination, may be hard to see.[8]

Therefore many neonatal services prefer to perform an MRI scan when the infant is near term, as well as routine cranial ultrasound, to avoid missing more subtle abnormalities.

References

- ↑ Cranial Ultrasound article on the WedMD website http://www.webmd.com/brain/cranial-ultrasound

- ↑ NHS Forth Valley Cranial Ultrasound guideline http://www.nhsforthvalley.com/__documents/qi/ce_guideline_wcdneonatal/cranialuss.pdf

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Intraventricular hemorrhage of the newborn

- ↑ Pediatric Periventricular Leukomalacia at eMedicine

- ↑ Auckland District Health Board Neonatal Cranial Ultrasound training resource "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-12-07. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Lissauer T, Fanaroff AA, Miall L, Fanaroff J, "Neonatology at a Glance", p187, John Wiley & Sons, 2015

- ↑ van Wezel-Meijler, G, "Neonatal Cranial Ultrasonography" pp85-90, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007

- ↑ van Wezel-Meijler G, Seggerda SJ, Leijser LM, "Cranial ultrasonography in neonates: role and limitations, Seminars in Perinatology, 34(1):28-38, 2010