Diagnosis of hearing loss

Identification of a hearing loss is usually conducted by a general practitioner medical doctor, otolaryngologist, certified and licensed audiologist, school or industrial audiometrist, or other audiometric technician. Diagnosis of the cause of a hearing loss is carried out by a specialist physician (audiovestibular physician) or otorhinolaryngologist.

Case history

A case history (usually a written form, with questionnaire) can provide valuable information about the context of the hearing loss, and indicate what kind of diagnostic procedures to employ. Case history will include such items as:

- major concern

- birth and pregnancy information

- medical history

- development history

- family history

- workplace environment

- home environment

Examination

- otoscopy, visual examination of the outer ear, ear canal, eardrum, and middle ear (through the translucent eardrum) using an optical instrument inserted into the ear canal called an otoscope

- tympanometry

- differential testing – the Weber, Rinne, Bing and Schwabach tests are simple manual tests of auditory function conducted with a low frequency (usually 512 Hz) tuning fork that can provide a quick indication of type of hearing loss: unilateral/bilateral, conductive, or other

Laboratory testing

In case of infection or inflammation, blood or other body fluids may be submitted for laboratory analysis.

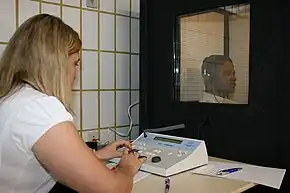

Hearing tests

Hearing loss is generally measured by playing generated or recorded sounds, and determining whether the person can hear them. Hearing sensitivity varies according to the frequency of sounds. To take this into account, hearing sensitivity can be measured for a range of frequencies and plotted on an audiogram.

Other method for quantifying hearing loss is a hearing test using a mobile application or hearing aid application, which includes a hearing test.[1][2] Hearing diagnosis using mobile application is similar to the audiometry procedure. As a result of hearing test, hearing thresholds at different frequencies (audiogram) are determined. Despite the errors in the measurements, application can help to diagnose hearing loss.[1] Audiogram, obtained using mobile application, can be used to adjust hearing aid application.[2]

Another method for quantifying hearing loss is a speech-in-noise test. As the name implies, a speech-in-noise test gives an indication of how well one can understand speech in a noisy environment. A person with a hearing loss will often be less able to understand speech, especially in noisy conditions. This is especially true for people who have a sensorineural loss – which is by far the most common type of hearing loss. As such, speech-in-noise tests can provide valuable information about a person's hearing ability, and can be used to detect the presence of a sensorineural hearing loss. A recently developed digit-triple speech-in-noise test may be a more efficient screening test.[3]

Otoacoustic emissions test is an objective hearing test that may be administered to toddlers and children too young to cooperate in a conventional hearing test. The test is also useful in older children and adults and is an important measure in diagnosing auditory neuropathy described above.

Auditory brainstem response testing is an electrophysiological test used to test for hearing deficits caused by pathology within the ear, the cochlear nerve and also within the brainstem. This test can be used to identify delay in the conduction of neural impulses due to tumours or inflammation but can also be an objective test of hearing thresholds. Other electrophysiological tests, such as cortical evoked responses, can look at the hearing pathway up to the level of the auditory cortex.

Scans

MRI and CT scans can be useful to identify the pathology of many causes of hearing loss. They are only needed in selected cases.

Classification

Hearing loss is categorized by type, severity, and configuration. Furthermore, a hearing loss may exist in only one ear (unilateral) or in both ears (bilateral). Hearing loss can be temporary or permanent, sudden or progressive.

Severity

The severity of a hearing loss is ranked according to ranges of nominal thresholds in which a sound must be so it can be detected by an individual. It is measured in decibels of hearing loss, or dB HL. The measurement of hearing loss in an individual is conducted over several frequencies, mostly 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz. The hearing loss of the individual is the average of the hearing loss values over the different frequencies. Hearing loss can be ranked differently according to different organisations; and so, in different countries different systems are in use.

Hearing loss may be ranked as slight, mild, moderate, moderately severe, severe or profound as defined below:

- Slight: between 16 and 25 dB HL

- Mild:

- for adults: between 26 and 40 dB HL

- for children: between 20 and 40 dB HL[4]

- Moderate: between 41 and 54 dB HL[4]

- Moderately severe: between 55 and 70 dB HL[4]

- Severe: between 71 and 90 dB HL[4]

- Profound: 91 dB HL or greater[4]

- Totally deaf: Have no hearing at all. This is called anacusis.

The 'Audiometric Classifications of Hearing Impairment' according to the International Bureau Audiophonology (BIAP) in Belgium is as follows:[5]

- Normal or subnormal hearing: average tone loss is equal or below 20 dB HL

- Mild hearing loss: average tone loss between 21 and 40 dB HL

- Moderate hearing loss

- First degree: average tone loss between 41 and 55 dB HL

- Second degree: average tone loss between 56 and 70 dB HL

- Severe hearing loss

- First degree: average tone loss between 71 and 80 dB HL

- Second degree: average tone loss between 81 and 90 dB HL

- Very severe hearing loss

- First degree: average tone loss between 91 and 100 dB HL

- Second degree: average tone loss between 101 and 110 dB HL

- Third degree: average tone loss between 111 and 119 dB HL

- Total hearing loss or Cophosis: average tone loss is equal or more than 120 dB HL

Hearing loss may affect one or both ears. If both ears are affected, then one ear may be more affected than the other. Thus it is possible, for example, to have normal hearing in one ear and none at all in the other, or to have mild hearing loss in one ear and moderate hearing loss in the other.

For certain legal purposes such as insurance claims, hearing loss is described in terms of percentages. Given that hearing loss can vary by frequency and that audiograms are plotted with a logarithmic scale, the idea of a percentage of hearing loss is somewhat arbitrary, but where decibels of loss are converted via a legally recognized formula, it is possible to calculate a standardized "percentage of hearing loss", which is suitable for legal purposes only.

Type

There are three main types of hearing loss, conductive hearing loss, sensorineural hearing loss. Combinations of conductive and sensorineural hearing losses are called a mixed hearing loss.[4] An additional problem which is increasingly recognised is auditory processing disorder which is not a hearing loss as such but a difficulty perceiving sound.

- Conductive hearing loss

Conductive hearing loss is present when the sound is not reaching the inner ear, the cochlea. This can be due to external ear canal malformation, dysfunction of the eardrum or malfunction of the bones of the middle ear. The eardrum may show defects from small to total resulting in hearing loss of different degree. Scar tissue after ear infections may also make the eardrum dysfunction as well as when it is retracted and adherent to the medial part of the middle ear.

Dysfunction of the three small bones of the middle ear – malleus, incus, and stapes – may cause conductive hearing loss. The mobility of the ossicles may be impaired for different reasons including a boney disorder of the ossicles called otosclerosis and disruption of the ossicular chain due to trauma, infection or ankylosis may also cause hearing loss.

- Sensorineural hearing loss

Sensorineural hearing loss is one caused by dysfunction of the inner ear, the cochlea or the nerve that transmits the impulses from the cochlea to the hearing centre in the brain. The most common reason for sensorineural hearing loss is damage to the hair cells in the cochlea. Depending on the definition it could be estimated that more than 50% of the population over the age of 70 has impaired hearing.[6]

- Central deafness

Damage to the brain can lead to a central deafness. The peripheral ear and the auditory nerve may function well but the central connections are damaged by tumour, trauma or other disease and the patient is unable to process speech information.

- Mixed hearing loss

Mixed hearing loss is a combination of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. Chronic ear infection (a fairly common diagnosis) can cause a defective ear drum or middle-ear ossicle damages, or both. In addition to the conductive loss, a sensory component may be present.

- Central auditory processing disorder

This is not an actual hearing loss but gives rise to significant difficulties in hearing. One kind of auditory processing disorder is King-Kopetzky syndrome, which is characterized by an inability to process out background noise in noisy environments despite normal performance on traditional hearing tests. An auditory processing disorders is sometimes linked to language disorders in persons of all ages.

Configuration

The shape of an audiogram shows the relative configuration of the hearing loss, such as a Carhart notch for otosclerosis, 'noise' notch for noise-induced damage, high frequency rolloff for presbycusis, or a flat audiogram for conductive hearing loss. In conjunction with speech audiometry, it may indicate central auditory processing disorder, or the presence of a schwannoma or other tumor. There are four general configurations of hearing loss:

1. Flat: thresholds essentially equal across test frequencies.

2. Sloping: lower (better) thresholds in low-frequency regions and higher (poorer) thresholds in high-frequency regions.

3. Rising: higher (poorer) thresholds in low-frequency regions and lower (better) thresholds in higher-frequency regions.

4. Trough-shaped ("cookie-bite" or "U" shaped): greatest hearing loss in the mid-frequency range, with lower (better) thresholds in low- and high-frequency regions.

Unilateral and bilateral

People with unilateral hearing loss or single-sided deafness (SSD) have difficulty in:

- hearing conversation on their impaired side

- localizing sound

- understanding speech in the presence of background noise.

In quiet conditions, speech discrimination is approximately the same for normal hearing and those with unilateral deafness; however, in noisy environments speech discrimination varies individually and ranges from mild to severe.

One reason for the hearing problems these patients often experience is due to the head shadow effect. Newborn children with no hearing on one side but one normal ear could still have problems.[7] Speech development could be delayed and difficulties to concentrate in school are common. More children with unilateral hearing loss have to repeat classes than their peers. Taking part in social activities could be a problem. Early aiding is therefore of utmost importance.[8][9]

References

- 1 2 Shojaeemend H, Ayatollahi H (October 2018). "Automated Audiometry: A Review of the Implementation and Evaluation Methods". Healthcare Informatics Research. 24 (4): 263–275. doi:10.4258/hir.2018.24.4.263. PMC 6230538. PMID 30443414.

- 1 2 Keidser G, Convery E (April 2016). "Self-Fitting Hearing Aids: Status Quo and Future Predictions". Trends in Hearing. 20: 233121651664328. doi:10.1177/2331216516643284. PMC 4871211. PMID 27072929.

- ↑ Jansen S, Luts H, Dejonckere P, van Wieringen A, Wouters J (2013). "Efficient hearing screening in noise-exposed listeners using the digit triplet test" (PDF). Ear and Hearing. 34 (6): 773–8. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e318297920b. PMID 23782715. S2CID 11858630.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Elzouki AY (2012). Textbook of clinical pediatrics (2 ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 602. ISBN 9783642022012. Archived from the original on 2015-12-14.

- ↑ "BIAP Recommendation 02/1 bis - AUDIOMETRIC CLASSIFICATION OF HEARING IMPAIRMENTS". biap.org. International Bureau Audiophonology. 26 October 1996. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ↑ Russell JL, Pine HS, Young DL (August 2013). "Pediatric cochlear implantation: expanding applications and outcomes". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 60 (4): 841–63. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2013.04.008. PMID 23905823.

- ↑ Lieu JE (May 2004). "Speech-language and educational consequences of unilateral hearing loss in children". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 130 (5): 524–30. doi:10.1001/archotol.130.5.524. PMID 15148171.

- ↑ Kitterick PT, O'Donoghue GM, Edmondson-Jones M, Marshall A, Jeffs E, Craddock L, Riley A, Green K, O'Driscoll M, Jiang D, Nunn T, Saeed S, Aleksy W, Seeber BU (Aug 11, 2014). "Comparison of the benefits of cochlear implantation versus contra-lateral routing of signal hearing aids in adult patients with single-sided deafness: study protocol for a prospective within-subject longitudinal trial". BMC Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders. 14 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1472-6815-14-7. PMC 4141989. PMID 25152694.

- ↑ Riss D, Arnoldner C, Baumgartner WD, Blineder M, Flak S, Bachner A, Gstoettner W, Hamzavi JS (December 2014). "Indication criteria and outcomes with the Bonebridge transcutaneous bone-conduction implant". The Laryngoscope. 124 (12): 2802–6. doi:10.1002/lary.24832. PMID 25142577. S2CID 206202070.