Eisenmenger syndrome

| Eisenmenger syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: ES, Eisenmenger's reaction, Eisenmenger physiology, or Tardive cyanosis | |

| |

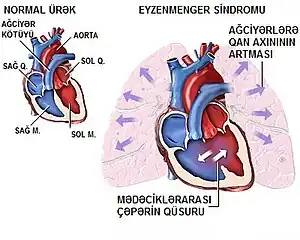

| Schematic drawing showing the principles of Eisenmenger's syndrome | |

Eisenmenger syndrome or Eisenmenger's syndrome is defined as the process in which a long-standing left-to-right cardiac shunt caused by a congenital heart defect (typically by a ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, or less commonly, patent ductus arteriosus) causes pulmonary hypertension[1][2] and eventual reversal of the shunt into a cyanotic right-to-left shunt. Because of the advent of fetal screening with echocardiography early in life, the incidence of heart defects progressing to Eisenmenger syndrome has decreased.

Eisenmenger syndrome in a pregnant mother can cause serious complications,[3] though successful delivery has been reported.[4] Maternal mortality ranges from 30% to 60%, and may be attributed to fainting spells, blood clots forming in the veins and traveling to distant sites, hypovolemia, coughing up blood or preeclampsia. Most deaths occur either during or within the first weeks after delivery.[5] Pregnant women with Eisenmenger syndrome should be hospitalized after the 20th week of pregnancy, or earlier if clinical deterioration occurs.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of Eisenmenger syndrome include the following:[6]

- Cyanosis (a blue tinge to the skin resulting from lack of oxygen)

- High red blood cell count

- Swollen or clubbed fingertips (clubbing)

- Fainting (also known as syncope)

- Heart failure

- Abnormal heart rhythms

- Bleeding disorders

- Coughing up blood

- Iron deficiency

- Infections (endocarditis and pneumonia)

- Kidney problems

- Stroke

- Gout (rarely) due to increased uric acid resorption and production with impaired excretion[7]

- Gallstones

One of the most severe and common complications of Eisenmenger syndrome is cardiac arrhythmia, especially supraventricular arrhythmias. Approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with Eisenmenger syndrome were also found to have these arrhythmias during routine ECG screenings. These arrhythmias have worse prognosis in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome, compared to the general population, and can be a source of sudden cardiac death.[8]

Causes

A number of congenital heart defects can cause Eisenmenger syndrome, including atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and more complex types of acyanotic heart disease.[1]

Pathogenesis

The reason Eisenmenger syndrome often presents later in life can be explained by alterations of the normal physiology of the heart and the maladaptive responses that occur over time. The larger and more muscular left side of the heart must generate the high pressure required to supply blood to the extensive, high-resistance systemic circulation. In contrast, the smaller, right side of the heart must generate a much lower pressure in order to pass blood through the low-resistance, high compliance circulation of the lungs. The lungs are able to accomplish this low-resistance circulation largely due to the fact that the length of the pulmonary circulation is smaller, and because much of the circuitry is in parallel rather than in series.

If a significant anatomic defect (i.e. a hole or breach) exists between the two sides of the heart, a shunt will occur, causing blood to flow down the normal pressure gradient from the left side to the right side. The amount of blood shunted is proportional to the size of the defect, and the beat-to-beat volume of blood pumped through a left-to-right breach is a percentage of anticipated cardiac output (CO) of the left ventricle. Clinically a low index or percentage of CO ejected through a shunt is harmless; a high index or percentage of CO ejected through a left-to-right shunt heralds Eisenmenger's physiology.

The left-to-right shunting of blood results in abnormally high blood flow and pressure directed to the right heart circulation, gradually leading to maladaptive changes that ultimately result in pulmonary hypertension. Increased right-sided blood volume and pressure causes a cascade of pathologic damage to the delicate pulmonary capillaries, causing them to be incrementally replaced with scar tissue. Scar (dead lung tissue) does not contribute to oxygen transfer, therefore decreasing the useful volume of the pulmonary vasculature. The scar tissue also provides less flexibility and compliance than normal lung tissue, causing further increases in pulmonary blood pressure, and the weakened heart must pump harder to continue supplying the lungs, leading to damage of more capillaries. It is because of this maladaptive response that at the onset of Eisenmenger syndrome, the damage is considered irreversible, even if the underlying heart defect is corrected after the fact.

Eventually, due to increased resistance and decreased compliance of the pulmonary vessels, elevated pulmonary pressures cause the myocardium of the right heart to hypertrophy (RVH). The onset of Eisenmenger syndrome begins when right ventricular hypertrophy causes right heart pressures to exceed that of the left heart, leading to reversal of blood flow through the shunt (i.e., blood moves from the right side of the heart to the left side). As a consequence, deoxygenated blood returning from the body bypasses the lungs through the reversed shunt and proceeds directly to systemic circulation, leading to cyanosis and resultant organ damage.

The defect, now a right-to-left shunt, causes reduced oxygen saturation in the arterial blood due to mixing of oxygenated blood returning from the lungs with the deoxygenated blood returning from systemic circulation. This decreased saturation is sensed by the kidneys, resulting in a compensatory increase in erythropoietin production and an increased production of red blood cells in an attempt to increase oxygen delivery. As the bone marrow increases erythropoiesis, the systemic reticulocyte count and the risk for hyperviscosity syndrome increases. Reticulocytes are less efficient at carrying oxygen as mature red cells, and they are less deformable, causing impaired transit through capillary beds. This contributes to the death of pulmonary capillary beds.

A person with Eisenmenger syndrome is paradoxically subject to the possibility of both uncontrolled bleeding due to damaged capillaries and high pressure, as well as spontaneous clots due to hyperviscosity and stasis of blood.

Diagnosis

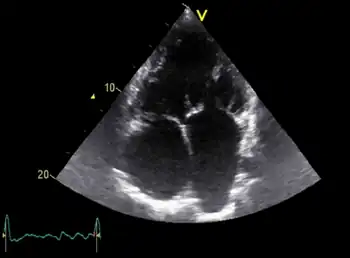

Diagnosis of Eisenmenger syndrome is typically conducted via transthoracic echocardiography, which facilitates the identification and evaluation of shunts, anatomical defects, and ventricular function. Following diagnosis, or in some cases of inconclusive diagnosis, a cardiac catheter may be used to both confirm the diagnosis and to assess the patient's pulmonary arterial pressure, an important predictive value for prognosis and treatment.[8]

Treatment

If the inciting defect in the heart is identified before it causes significant pulmonary hypertension, it can normally be repaired through surgery, preventing the disease.[9] After pulmonary hypertension is sufficient to reverse the blood flow through the defect, however, the maladaptation is considered irreversible, and a heart–lung transplant or a lung transplant with repair of the heart is the only curative option. Transplantation is the final therapeutic option and only for patients with poor prognosis and quality of life. Timing and appropriateness of transplantation remain difficult decisions.[5] 5-year and 10-year survival ranges between 70% and 80%, 50% and 70%, 30% and 50%, respectively.[10][11][12] Since the average life expectancy of patients after lung transplantation is as low as 30% at 5 years, patients with reasonable functional status related to Eisenmenger syndrome have improved survival with conservative medical care compared with transplantation.[13]

Various medicines and therapies for pulmonary hypertension are under investigation for treatment of the symptoms.[14] Air filters for intravenous lines are recommended for persons with Eisenmenger syndrome who have been hospitalized to reduce the risk of accidental introduction of air into the veins due to the increased risk for paradoxical air embolism. If air is introduced into the veins and travels through the ventricular septal defect into the arterial circulation, a stroke may occur.

Antiarrhythmic drugs are important for many patients with Eisenmenger syndrome, as evidence suggests that arrhythmia-induced sudden cardiac death may be the leading cause of death among patients with the disease. These therapies generally aim to restore and maintain sinus rhythm, but the specific interventions chosen will depend on the nature of the patient's arrhythmia.[8]

Etymology

Eisenmenger syndrome was named[15] by Paul Wood after Victor Eisenmenger, who first described[16] the condition in 1897.[17]

References

- 1 2 Jensen AS, Iversen K, Vejlstrup NG, Hansen PB, Søndergaard L (April 2009). "[Eisenmenger syndrome]". Ugeskrift for Laeger (in dansk). 171 (15): 1270–5. PMID 19416617.

- ↑ "Eisenmenger syndrome" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Siddiqui S, Latif N (2008). "PGE1 nebulisation during caesarean section for Eisenmenger's syndrome: a case report". J Med Case Rep. 2 (1): 149. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-149. PMC 2405798. PMID 18466628.

- ↑ Makaryus AN, Forouzesh A, Johnson M (November 2006). "Pregnancy in the patient with Eisenmenger's syndrome". Mt. Sinai J. Med. 73 (7): 1033–6. PMID 17195894. Archived from the original on 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- 1 2 Curr Cardiol Rev. 2010 November; 6(4): 363–372.The Adult Patient with Eisenmenger Syndrome: A Medical Update after Dana Point Part III: Specific Management and Surgical Aspects Erwin Oechslin, Siegrun Mebus, Ingram Schulze-Neick, Koichiro Niwa, Pedro T Trindade, Andreas Eicken, Alfred Hager, Irene Lang, John Hess, and Harald Kaemmerer PMC 3083818

- ↑ "Eisenmenger syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ↑ Braunwald E. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. P 1617-1618. Ann Intern Med 1998; 128:745-755

- 1 2 3 Diller, Gerhard-Paul; Gatzoulis, Michael A. (2007-02-27). "Pulmonary Vascular Disease in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease". Circulation. 115 (8): 1039–1050. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592386. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 17325254. S2CID 10479313. Archived from the original on 2023-01-06. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ "Eisenmenger syndrome". NIH MedLine Plus. 2010-02-05. Archived from the original on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Goerler H, Simon A, Gohrbandt B, et al. Heart-lung and lung transplantation in grown-up congenital heart disease: long-term single centre experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32(6):926–31. [PubMed]

- ↑ Waddell TK, Bennett L, Kennedy R, Todd TR, Keshavjee SH. Heart-lung or lung transplantation for Eisenmenger syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21(7):731–7. [PubMed]

- ↑ Heart-lung transplantation for Eisenmenger syndrome: early and long-term results. Stoica SC, McNeil KD, Perreas K, Sharples LD, Satchithananda DK, Tsui SS, Large SR, Wallwork J Ann Thorac Surg. 2001 Dec; 72(6):1887-91.

- ↑ Beghetti, Maurice; Galiè, Nazzareno (Mar 2009). "Eisenmenger Syndrome". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 53 (9): 733–740. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.025. PMID 19245962. Archived from the original on 2022-06-20. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ "Eisenmenger Syndrome Treatment & Management". MedScape Reference. 2008-06-05. Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Wood, P (1958). "Pulmonary hypertension with special reference to the vasoconstrictive factor". British Heart Journal. 20 (4): 557–70. doi:10.1136/hrt.20.4.557. PMC 491807. PMID 13584643.

- ↑ Eisenmenger V. Die angeborenen Defekte der Kammerscheidewände des Herzens. The condition was first mentioned by Hippocrates, the Greek physician. Zeitschr Klin Med 1897;32(Supplement):1-28.

- ↑ synd/3034 at Who Named It?

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|