Polycythemia vera

| Polycythaemia vera | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Polycythaemia vera, erythremia, primary polycythemia, Vaquez disease, Osler-Vaquez disease, polycythemia rubra vera[1] | |

| |

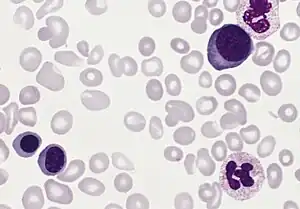

| Blood smear from a person with polycythemia vera | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Itchiness, headaches, blurry vision, burning pain in the hands or feet, reddish skin[2] |

| Complications | Thrombosis, myelofibrosis, hyperviscosity syndrome, leukemia[2] |

| Usual onset | 60 years[2] |

| Duration | Long-term[3] |

| Diagnostic method | CBC, bone marrow biopsy, genetic testing after ruling out other causes of polycythemia[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other causes of polycythemia, essential thrombocythemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia[2] |

| Treatment | Removing blood, aspirin[2] |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy ~14 years with treatment[2] |

| Frequency | 5 per 10,000[3] |

Polycythemia vera (PCV) is a disorder in which the bone marrow makes too many red blood cells, and occasionally white blood cells and platelets.[2] Symptoms may include itchiness, headaches, blurry vision, burning pain in the hands or feet, and reddish skin.[2] Complications can include blood clots, myelofibrosis, hyperviscosity syndrome, and leukemia.[2]

More than 90% of cases are due to a mutation of the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) gene in a group of blood forming cells.[2] This occurs after birth and for an unclear reason.[3] This results in increased sensitivity to growth factors.[2] It is a type of myeloproliferative neoplasm.[2] Diagnosis is based based on a complete blood cell count, bone marrow biopsy, and genetic testing after ruling out other causes of polycythemia.[2]

Treatment consists removing blood and aspirin.[2] Other measures include a healthy lifestyle.[2] In older people or those with a higher risk of blood clots hydroxyurea, interferon, busulfan may be recommended.[2] Occationally removal of the spleen is required.[2] Life expectancy is around 18 months without treatment and 14 years with treatment.[2]

The condition is uncommon, affected about 5 per 10,000.[3] The typical age of onset is 60 and the condition is rare under the age of 20.[2][3] Males and females are affected with similar frequency.[2] The condition was first described in 1892.[3]

Signs and symptoms

People with polycythemia vera can be asymptomatic.[4] A classic symptom of polycythemia vera is pruritus or itching, particularly after exposure to warm water (such as when taking a bath),[5] which may be due to abnormal histamine release[6][7] or prostaglandin production.[8] Such itching is present in approximately 40% of people.[9] Gout may be present in up to 20%.[9] Peptic ulcer disease is also common; most likely due to increased histamine from mast cells, but may be related to an increased susceptibility to infection with the ulcer-causing bacterium H. pylori.[10] Another possible mechanism for the development for peptic ulcer is increased histamine release and gastric hyperacidity related with polycythemia vera.

A classic symptom of polycythemia vera (and the related myeloproliferative disease essential thrombocythemia) is erythromelalgia.[11] This is a burning pain in the hands or feet, usually accompanied by a reddish or bluish coloration of the skin. Erythromelalgia is caused by an increased platelet count or increased platelet "stickiness" (aggregation), resulting in the formation of tiny blood clots in the vessels of the extremity; it responds rapidly to treatment with aspirin.[12][13]

People are prone to the development of blood clots (thrombosis). A major thrombotic complication (e.g. heart attack, stroke, deep venous thrombosis, or Budd-Chiari syndrome) may sometimes be the first symptom or indication that a person has polycythemia vera. Headaches, lack of concentration and fatigue are common symptoms as well.

Pathophysiology

Polycythemia vera, being a primary polycythemia, is caused by neoplastic proliferation and maturation of erythroid, megakaryocytic and granulocytic elements to produce what is referred to as panmyelosis. In contrast to secondary polycythemias, PCV is associated with a low serum level of the hormone erythropoietin (EPO). Instead, PCV cells often carry activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase (JAK2) gene, which acts in signaling pathways of the EPO-receptor, making those cells proliferate independent from EPO.[14]

Diagnosis

Physical exam findings are non-specific, but may include enlarged liver or spleen, plethora, or gouty nodules. The diagnosis is often suspected on the basis of laboratory tests. Common findings include an elevated hemoglobin level and hematocrit, reflecting the increased number of red blood cells; the platelet count or white blood cell count may also be increased. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is decreased due to an increase in zeta potential. Because polycythemia vera results from an essential increase in erythrocyte production, patients have normal blood oxygenation and a low erythropoietin (EPO) level.

In primary polycythemia, there may be 8 to 9 million and occasionally 11 million erythrocytes per cubic millimeter of blood (a normal range for adults is 4-6), and the hematocrit may be as high as 70 to 80%. In addition, the total blood volume sometimes increases to as much as twice normal. The entire vascular system can become markedly engorged with blood, and circulation times for blood throughout the body can increase up to twice the normal value. The increased numbers of erythrocytes can cause the viscosity of the blood to increase as much as five times normal. Capillaries can become plugged by the very viscous blood, and the flow of blood through the vessels tends to be extremely sluggish.

As a consequence of the above, people with untreated polycythemia vera are at a risk of various thrombotic events (deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism), heart attack and stroke, and have a substantial risk of Budd-Chiari syndrome (hepatic vein thrombosis),[15] or myelofibrosis. The condition is considered chronic; no cure exists. Symptomatic treatment (see below) can normalize the blood count and most can live a normal life for years.

The disease appears more common in Jews of European extraction than in most non-Jewish populations. Some familial forms of polycythemia vera are noted, but the mode of inheritance is not clear.

A mutation in the JAK2 kinase (V617F) is strongly associated with polycythemia vera.[16][17] JAK2 is a member of the Janus kinase family and makes the erythroid precursors hypersensitive to erythropoietin (EPO). This mutation may be helpful in making a diagnosis or as a target for future therapy.

Following history and examination, the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH) recommend the following tests are performed:

- full blood count/film (raised haematocrit; neutrophils, basophils, platelets raised in half of people)

- JAK2 mutation

- serum ferritin

- renal and liver function tests

If the JAK2 mutation is negative and there is no obvious secondary causes the BCSH suggest the following tests:

- red cell mass

- arterial oxygen saturation

- abdominal ultrasound

- serum erythropoietin level

- bone marrow aspirate and trephine

- cytogenetic analysis

- erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E) culture

Other features that may be seen in polycythemia vera include a low ESR and a raised leukocyte alkaline phosphatase.

The diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera have recently been updated by the BCSH. This replaces the previous Polycythemia Vera Study Group criteria.

JAK2-positive polycythaemia vera - diagnosis requires both criteria to be present:

| Criteria | Notes |

|---|---|

| A1 | High erythrocyte volume fraction (EVF or haematocrit) (>0.52 in men, >0.48 in women) OR raised red cell mass (>25% above predicted) |

| A2 | Mutation in JAK2 |

JAK2-negative polycythemia vera - diagnosis requires A1 + A2 + A3 + either another A or two B criteria:

| Criteria | Notes |

|---|---|

| A1 | Raised red cell mass (>25% above predicted) OR haematocrit >0.60 in men, >0.56 in women |

| A2 | Absence of mutation in JAK2 |

| A3 | No cause of secondary erythrocytosis |

| A4 | Palpable splenomegaly |

| A5 | Presence of an acquired genetic abnormality (excluding BCR-ABL) in the haematopoietic cells |

| B1 | Thrombocytosis (platelet count >450 * 109/l) |

| B2 | Neutrophil leucocytosis (neutrophil count > 10 * 109/l in non-smokers; > 12.5*109/l in smokers) |

| B3 | Radiological evidence of splenomegaly |

| B4 | Endogenous erythroid colonies or low serum erythropoietin |

Treatment

Untreated, polycythemia vera can be fatal.[18][19] Research has found that the "1.5-3 years of median survival in the absence of therapy has been extended to at least 10-20 years because of new therapeutic tools."[20]

As the condition cannot be cured, treatment focuses on treating symptoms and reducing thrombotic complications by reducing the erythrocyte levels.

Phlebotomy is one form of treatment, which often may be combined with other therapies. The removal of blood from the body induces iron deficiency, thereby decreasing the haemoglobin / hematocrit level, and reducing the risk of blood clots. Phlebotomy is typically performed to bring their hematocrit (red blood cell percentage) down below 45 for men or 42 for women.[21] It has been observed that phlebotomy also reduces cognitive impairment (improves cognition).[22]

Low dose aspirin (75–81 mg daily) is often prescribed. Research has shown that aspirin reduces the risk for various thrombotic complications.

Chemotherapy for polycythemia may be used, either for maintenance, or when the rate of bloodlettings required to maintain normal hematocrit is not acceptable, or when there is significant thrombocytosis or intractable pruritus. This is usually with a "cytoreductive agent" (hydroxyurea, also known as hydroxycarbamide).

The tendency of some practitioners to avoid chemotherapy if possible, especially in young people, is a result of research indicating possible increased risk of transformation to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). While hydroxyurea is considered safer in this aspect, there is still some debate about its long-term safety.[23]

In the past, injection of radioactive isotopes (principally phosphorus-32) was used as another means to suppress the bone marrow. Such treatment is now avoided due to a high rate of AML transformation.

Other therapies include interferon injections, and in cases where secondary thrombocytosis (high platelet count) is present, anagrelide may be prescribed.

Bone marrow transplants are rarely undertaken in people with polycythemia; since this condition is non-fatal if treated and monitored, the benefits rarely outweigh the risks involved in such a procedure.

There are indications that with certain genetic markers, erlotinib may be an additional treatment option for this condition.[24]

The JAK2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, is also used to treat polycythemia.[25]

Epidemiology

Polycythemia vera occurs in all age groups,[26] although the incidence increases with age. One study found the median age at diagnosis to be 60 years,[9] while a Mayo Clinic study in Olmsted County, Minnesota found that the highest incidence was in people aged 70–79 years.[27] The overall incidence in the Minnesota population was 1.9 per 100,000 person-years, and the disease was more common in men than women.[27] A cluster around a toxic site was confirmed in northeast Pennsylvania in 2008. [28]

See also

References

- ↑ "polycythemia vera." at Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived 2010-08-13 at the Wayback Machine 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 21 Sep. 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Lu, X; Chang, R (January 2020). "Polycythemia Vera". PMID 32491592.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Polycythemia Vera". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ↑ [Polycythemia vera EBSCO database] verified by URAC; accessed from Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- ↑ Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A (2010). "Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management". Eur J Clin Invest. 40 (9): 828–34. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x. PMID 20597963.

- ↑ Steinman H, Kobza-Black A, Lotti T, Brunetti L, Panconesi E, Greaves M (1987). "Polycythaemia rubra vera and water-induced pruritus: blood histamine levels and cutaneous fibrinolytic activity before and after water challenge". Br J Dermatol. 116 (3): 329–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05846.x. PMID 3567071.

- ↑ Jackson N, Burt D, Crocker J, Boughton B (1987). "Skin mast cells in polycythaemia vera: relationship to the pathogenesis and treatment of pruritus". Br J Dermatol. 116 (1): 21–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb05787.x. PMID 3814512.

- ↑ Fjellner B, Hägermark O (1979). "Pruritus in polycythemia vera: treatment with aspirin and possibility of platelet involvement". Acta Derm Venereol. 59 (6): 505–12. PMID 94209.

- 1 2 3 Berlin NI (1975). "Diagnosis and classification of polycythemias". Semin Hematol. 12 (4): 339–51. PMID 1198126.

- ↑ Torgano G, Mandelli C, Massaro P, Abbiati C, Ponzetto A, Bertinieri G, Bogetto S, Terruzzi E, de Franchis R (2002). "Gastroduodenal lesions in polycythaemia vera: frequency and role of Helicobacter pylori". Br J Haematol. 117 (1): 198–202. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03380.x. PMID 11918555.

- ↑ van Genderen P, Michiels J (1997). "Erythromelalgia: a pathognomonic microvascular thrombotic complication in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera". Semin Thromb Hemost. 23 (4): 357–63. doi:10.1055/s-2007-996109. PMID 9263352.

- ↑ Michiels J (1997). "Erythromelalgia and vascular complications in polycythemia vera". Semin Thromb Hemost. 23 (5): 441–54. doi:10.1055/s-2007-996121. PMID 9387203.

- ↑ Landolfi R, Ciabattoni G, Patrignani P, Castellana M, Pogliani E, Bizzi B, Patrono C (1992). "Increased thromboxane biosynthesis in patients with polycythemia vera: evidence for aspirin-suppressible platelet activation in vivo". Blood. 80 (8): 1965–71. doi:10.1182/blood.V80.8.1965.1965. PMID 1327286.

- ↑ Kumar, et al.: Robbin's Basic Pathology, 8th edition, Saunders, 2007

- ↑ Thurmes PJ, Steensma DP (July 2006). "Elevated serum erythropoietin levels in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome secondary to polycythemia vera: clinical implications for the role of JAK2 mutation analysis". Eur. J. Haematol. 77 (1): 57–60. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2006.00667.x. PMID 16827884.

- ↑ Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, Vassiliou GS, Bench AJ, Boyd EM, Curtin N, Scott MA, Erber WN, Green AR (2005). "Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders". Lancet. 365 (9464): 1054–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. PMID 15781101. S2CID 24419497.

- ↑ Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, Ebert BL, Wernig G, Huntly BJ, Boggon TJ, Wlodarska I, Clark JJ, Moore S, Adelsperger J, Koo S, Lee JC, Gabriel S, Mercher T, D'Andrea A, Frohling S, Dohner K, Marynen P, Vandenberghe P, Mesa RA, Tefferi A, Griffin JD, Eck MJ, Sellers WR, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Lee SJ, Gilliland DG (2005). "Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis". Cancer Cell. 7 (4): 387–97. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. PMID 15837627.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic staff. "Polycythemia vera - MayoClinic.com". Polycythemia vera: Definition. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2011-08-24. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "What Is Polycythemia Vera?". National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "Polycythemia Vera Follow-up". Archived from the original on 2012-05-18. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ Streiff MB, Smith B, Spivak JL (2002). "The diagnosis and management of polycythemia vera in the era since the Polycythemia Vera Study Group: a survey of American Society of Hematology members' practice patterns". Blood. 99 (4): 1144–9. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.4.1144. PMID 11830459.

- ↑ Di Pollina L, Mulligan R, Juillerat Van der Linden A, Michel JP, Gold G (2000). "Cognitive impairment in polycythemia vera: partial reversibility upon lowering of the hematocrit". Eur. Neurol. 44 (1): 57–9. doi:10.1159/000008194. PMID 10894997. S2CID 40928145.

- ↑ Björkholm, M; Derolf, AR; Hultcrantz, M; et al. (10 June 2011). "Treatment-related risk factors for transformation to acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in myeloproliferative neoplasms". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (17): 2410–5. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7542. PMC 3107755. PMID 21537037.

- ↑ Li Z, Xu M, Xing S, Ho W, Ishii T, Li Q, Fu X, Zhao Z (2007). "Erlotinib Effectively Inhibits JAK2V617F Activity and Polycythemia Vera Cell Growth". J Biol Chem. 282 (6): 3428–32. doi:10.1074/jbc.C600277200. PMC 2096634. PMID 17178722.

- ↑ Tefferi, A; Vannucchi, AM; Barbui, T (10 January 2018). "Polycythemia vera treatment algorithm 2018". Blood Cancer Journal. 8 (1): 3. doi:10.1038/s41408-017-0042-7. PMC 5802495. PMID 29321547.

- ↑ Passamonti F, Malabarba L, Orlandi E, Baratè C, Canevari A, Brusamolino E, Bonfichi M, Arcaini L, Caberlon S, Pascutto C, Lazzarino M (2003). "Polycythemia vera in young patients: a study on the long-term risk of thrombosis, myelofibrosis and leukemia". Haematologica. 88 (1): 13–8. PMID 12551821.

- 1 2 Anía B, Suman V, Sobell J, Codd M, Silverstein M, Melton L (1994). "Trends in the incidence of polycythemia vera among Olmsted County, Minnesota residents, 1935-1989". Am J Hematol. 47 (2): 89–93. doi:10.1002/ajh.2830470205. PMID 8092146.

- ↑ MICHAEL RUBINKAM (2008). "Cancer cluster confirmed in northeast Pennsylvania". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 2, 2008.

External links

- Voices of MPN: Polycythemia Vera Archived 2019-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- 11-141d. at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |