Follicular hyperplasia

| Follicular hyperplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Reactive follicular hyperplasia, Lymphoid nodular hyperplasia |

| |

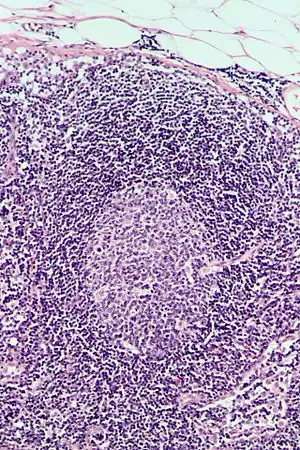

Follicular hyperplasia (FH) is a type of lymphoid hyperplasia and is classified as a lymphadenopathy, which means a disease of the lymph nodes. It is caused by a stimulation of the B cell compartment and by abnormal cell growth of secondary follicles. This typically occurs in the cortex without disrupting the lymph node capsule.[1] The follicles are pathologically polymorphous, are often contrasting and varying in size and shape.[2] Follicular hyperplasia is distinguished from follicular lymphoma in its polyclonality and lack of bcl-2 protein expression, whereas follicular lymphoma is monoclonal, and expresses bcl-2.[3]

Signs & Symptoms

Lymphadenopathies such as follicular hyperplasia can show various symptoms such as fever, chills, night sweats, unexplained weight loss and prominent localizing symptoms are non age and non-gender specific.[4]

Although human lymph nodes cannot be seen with the naked eye, if you press against the skin you can sometimes feel for swelling and pressure. Swelling of lymph nodes can range from pea sized to golf ball sized depending on the given condition. A person can have reactive lymph nodes throughout multiple areas of the body which can cause swelling, pain, warmth and tenderness.[5]

Causes

The following are examples of potential causes for reactive lymphadenopathies, all of which have predominantly follicular patterns:[1]

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Sjögren syndrome

- IgG4-related disease (IgG4-related lymphadenopathy) [6]

- Kimura disease

- Toxoplasmosis

- Syphilis

- Castleman disease

- Progressive transformation of germinal centers (PTGC)

Microorganisms can infect lymph nodes by causing pain and inflammation including redness and tenderness. Bacterial, fungal and viral infections including Bartonella, Staphylococcal, Granulomatous, Adenoviral and Lyme disease are all associated with follicular hyperplasia.[7]

Other autoimmune related diseases that are associated are rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus, dermatomyositis and Sjögren syndrome. Immunoglobulin G- related diseases are immune-mediated fibroinflammatory conditions that affect many organs in the body. Chronic inflammatory disorders such as Kimura disease are also the outcome of inflamed or enlarged lymph nodes. Parasitic bacterias such as Toxoplasma gondii or Treponema pallidum can cause enlargement of the lymph nodes as well. Other related causes such as lymphoproliferative conditions known as Castleman disease, or progressive transformation of germinal centers cause lymph node enlargement. Environmental conditions that may also play a role are animal or insect exposure, chronic medication usage and immunization status. The patient's occupational history such as metal work or coal mining may expose them to silicon or beryllium.[7]

Follicular hyperplasia is common in children and young adults, but is not limited to any age; it is also common among the elderly and is non-sex specific.[1] Children often experience reactive lymph nodes when they are younger due to new exposure of environmental pathogens, even without development of an infection.[5] Clinically, follicular hyperplasia lymphadenopathy is usually restricted to a single area on the body, but can also be on several parts of the body as well. Follicular hyperplasia is one of the most common types of lymphadenopathies and can be associated with paracortical and sinus hyperplasia.[1]

Mechanism

The specific pathology of follicular hyperplasia has not been fully understood yet. It is known, however, that a stimulation of the B cell compartment and by abnormal cell growth of secondary follicles are key factors to the pathology of follicular hyperplasia. This typically occurs in the cortex without disrupting the lymph node capsule.[1] It has also been described that the condition may stem from primary reactive lymphoid proliferations that may be triggered by an unidentified antigens or some sort of chronic irritation by ultimately causing lymph node enlargement.[8]

Lymph node enlargement can occur for many reasons. First of all, the lymph nodes function to act as a filter for the reticuloendothelial system. They contain multi-layered sinus by exposing B and T cell lymphocytes and macrophages and are found within the blood. When the immune system recognizes foreign proteins in order to mount an attack, it requires help from these blood cells. During this reaction the responding cell lines become duplicated in response to a foreign attack, and therefore increase in size. Node size is considered abnormal when it exceeds 1 cm, however this differs from children to adults.[4]

Localized or specific adenopathy often occur in clusters or groups of lymph nodes that can migrate to various areas of the body. Lymph nodes are distributed within all areas of the body and when enlarged, reflect the location of lymphatic drainage. The node appearance can range from tender, fixed or mobile and discrete or matted together.[4] It is important to note that reactive lymph nodes are not necessarily a bad thing, in fact they are a good indication that the lymphatic system is working hard. Lymph fluids can build up in lymph nodes as a way to trap harmful bacteria and other harmful pathogens in the body to prevent it from spreading to other areas.[5]

Substances that are present within the interstitial fluids such as microorganisms, antigens or even cancer can enter lymphatic vessels by forming the lymphatic fluids. Lymph nodes help filter these fluids by removing material towards the direction of blood circulation. When antigens are presented, the lymphocytes inside of the node trigger a response which can cause proliferation or cell enlargement. This is also referred to as reactive lymphadenopathy.[9]

Diagnosis

Follicular hyperplasia can be distinguished among other diseases by observing the density of a lymph follicle on low magnification. Lymph nodes with reactive follicles contain extensions outside its capsule, follicles present throughout the entire node, obvious centroblasts and the absence or diminishing mantle zones. Immunohistochemistry can help distinguish a difference between a patient with follicular lymphoma to follicular hyperplasia.[1] Reactive follicular hyperplasia does not express BCL2 proteins in B cell germinal centers and are absent light chain reaction in immunostaining and flow cytometry as well as absent IG rearrangements.[1]

Localized, or specific lymphadenopathies should be evaluated for etiologies that are associated with lymphatic drainage patterns. During a complete lymphatic physical examination, generalized lymphadenopathy may or may not be ruled out.[7]

BCL2 protein expression is usually absent in follicular hyperplasia but prominent in follicular lymphomas. A comparison with other stains that include germinal center markers such as BCL-6 or CD10 is useful to compare when determining a proper diagnosis.[1] CD10 positive cells are metalloproteinase which activate or deactivate peptides through proteolytic cleavage.[10]

An official diagnosis of follicular hyperplasia might include imagining such as a PET scan and a tissue biopsy, depending on the clinical location and also the location of lymphadenopathy.[7] A common blood panel test may help rule out other possible diagnosis, such as lymphomas based on the number of red, white and platelet cells found in the blood. If the patient has low blood cell counts, this can be an indication of lymphoma. Another indication of lymphoma compared to follicular hyperplasia is high levels of lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) and C-reactive proteins (CRP).[11] A lymph node biopsy may reveal an official diagnosis for lymphoma, by ruling out follicular hyperplasia which can be determined by the rate of proliferation.[11]

Treatment

Factors that identify etiology of the patient include age, duration of lymphadenopathy, external exposures, associated symptoms and location on the body.[1]

| Atenolol | Hydralazine | Penicillins | Pyrimethamine (Daraprim) |

| Captopril | Allopurinol | Phenytoin (Dilantin) | Quinidine |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | Primidone (Mysoline | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

Beta blockers such as Atenolol or ACE inhibitors like Captopril, can cause certain lymphadenopathies for some individuals. Captopril is an analog to proline and completely inhibits angiotensin converting enzymes (ACE) and as a result decreases angiostatin II production. It can also inhibit tumor angiogenesis through MMPs and endothelial cell migration, which can ultimately cause lymph node enlargement.[12]

Carbamazepine is an anticonvulsant that works by decreasing nerve impulses that are brought on by seizures. Some of the more serious side effects are allergic skin reactions and low blood cell counts. Other anticonvulsant medications, Phenytoin and Primidone, can also cause lymph node enlargement due to changes in the blood after drug administration.[13] Other medications such as Pyrimethamine, Quinidine and Trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole antibiotics also change blood chemistry after administration and can cause lymph node enlargement. Hydralazine and Allopurinol are medications that are prescribed to patients to lower their blood pressure and are vasodilators causing the blood cells to dilate.

A family history, regional exam and epidemiological cues are usually the most useful information to utilize for treatment options because it can help classify the patient's condition as either low risk, or high risk. Low risk, meaning the patient is not exposed to malignancy or serious disease and high risk means that they are. If the patient is not at risk for malignancy or serious illness, it is recommended for the physician to observe any changes or symptom resolutions within 3- 4 weeks. If the lymphadenopathy does not resolve the next step would be getting a biopsy.[4] Proceeding a tissue sample, an effective treatment for follicular hyperplasia is surgical removal of the lesion after an initial conformation of the disease based on the patients biopsy results.[8]

Prognosis

Typically follicular hyperplasia is categorized as a benign lymphadenopathy. This is usually almost always treatable, but only until it progresses into malignancy.[9] Therefore, follicular hyperplasia patients tend to live a long life until their condition is either treated or goes away on its own. Follicular hyperplasia becomes problematic when left untreated by increasing the risks for developing various types of cancers.[9]

Epidemiology

Follicular hyperplasia is one of the most common types of benign lymphadenopathies.[1] It can be typically found in children and young adults however all ages are subject to follicular hyperplasia, including the elderly. Lymphadenopathies such as follicular hyperplasia, are usually localized but can also be generalized and are non gender specific. Over 75% of all lymphadenopathies are observed as local, usually involving specifically the head and neck regions.[4] It has been estimated that patients who present lymphadenopathy has an estimated 1.1% chance of developing malignancy.[14]

The rate of childhood malignancy associated with lymphadenopathy is low, however this increases with age. A majority of reported cases in children are usually caused by infections or benign etiologies. In one study, 628 patients underwent a nodal biopsy and resulted benign or self-limited causes found in nearly 79% in patients younger than 30 years of age. This was also the case for nearly 59% of patients between the ages of 31-59 years old and 39% in patients that were older than 50 years of age. Lymphadenopathies that last more than 2 weeks or over one year and does not develop progression of cancer cells have a low chance of neoplastic effects.[14]

Current Research

During a recent 2019 study, a 51 year old woman was examined by medical professionals at the department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery, Tokyo Medical University Hospital, to treat an existing condition which was an inflamed mass of cells noted in patient's bottom left gum line. A sample biopsy was obtained from the patient's mouth and the indicated results showed benign lymphoid tissues. Further investigation under a microscope revealed lymphocytic tissues composed of scattered lymphoid follicles with obvious germinal centers and well differentiated lymphocytes surrounded by defiant mantle zones. Immunochemical staining revealed positivity for lymphoid particles CD20 and CD79. This study was significant because they were able to diagnose a very rare case of follicular lymphoid hyperplasia derived from an unusual origin site of the mouth, however they were unable to determine the onset of her condition. It is important to note that after the mass was removed there was no signs of recurrence after the first year of removal.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Weiss, L. M.; O'Malley, D (2013). "Benign lymphadenopathies". Modern Pathology. 26 Suppl 1: S88–96. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.176. PMID 23281438.

- ↑ Drew, Torigan; et al. (2001). "Lymphoid hyperplasia of stomach". American Journal of Roentgenology. 177 (1): 71–75. doi:10.2214/ajr.177.1.1770071. PMID 11418401.

- ↑ Sattar, Husain (2016). Fundamentals of Pathology. Chicago. ISBN 9780983224624.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Freeman, Andrew M.; Matto, Patricia (2020), "Adenopathy", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020622, retrieved 2020-11-06

- 1 2 3 "Reactive Lymph Node: Definition, Symptoms, Causes, and Diagnosis". Healthline. 2018-05-09. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ John H. Stone; Arezou Khosroshahi; Vikram Deshpande; et al. (October 2012). "Recommendations for the nomenclature of IgG4-related disease and its individual organ system manifestations". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 64 (10): 3061–3067. doi:10.1002/art.34593. PMC 5963880. PMID 22736240.

- 1 2 3 4 Gaddey, Heidi L.; Riegel, Angela M. (2016-12-01). "Unexplained Lymphadenopathy: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis". American Family Physician. 94 (11): 896–903. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 27929264.

- 1 2 3 Watanabe, Masato; Enomoto, Ai; Yoneyama, Yuya; Kohno, Michihide; Hasegawa, On; Kawase-Koga, Yoko; Satomi, Takafumi; Chikazu, Daichi (2019). "Follicular lymphoid hyperplasia of the posterior maxillary site presenting as uncommon entity: a case report and review of the literature". BMC Oral Health. 19 (1): 243. doi:10.1186/s12903-019-0936-9. ISSN 1472-6831. PMC 6849200. PMID 31711493.

- 1 2 3 "What is Lymphadenopathy?". News-Medical.net. 2017-01-08. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ Watanabe, Masato; Enomoto, Ai; Yoneyama, Yuya; Kohno, Michihide; Hasegawa, On; Kawase-Koga, Yoko; Satomi, Takafumi; Chikazu, Daichi (2019-11-11). "Follicular lymphoid hyperplasia of the posterior maxillary site presenting as uncommon entity: a case report and review of the literature". BMC Oral Health. 19 (1): 243. doi:10.1186/s12903-019-0936-9. ISSN 1472-6831. PMC 6849200. PMID 31711493.

- 1 2 "Lymphoma Diagnosis Using Blood Panels, Imaging Tests, and Biopsies". Healthline. 2019-12-18. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- ↑ PubChem. "Captopril". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- ↑ "Carbamazepine | Side Effects, Dosage, Uses, and More". Healthline. 2017-11-08. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- 1 2 Bazemore, Andrew; Smucker, Douglas R. (2002-12-01). "Lymphadenopathy and Malignancy". American Family Physician. 66 (11): 2103–10. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 12484692.