Foreign body in alimentary tract

| Foreign body in alimentary tract | |

|---|---|

| |

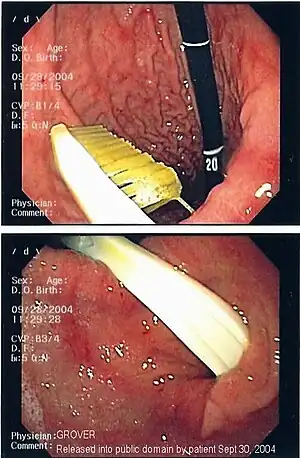

| A foreign body - in this case a swallowed toothbrush - located in the stomach cavity by using an endoscope. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, gastroenterology |

One of the most common locations for a foreign body is the alimentary tract. It is possible for foreign bodies to enter the from the mouth,[1] or from the rectum.[2]

The objects most commonly swallowed by children are coins.[3] Meat impaction, resulting in esophageal food bolus obstruction is more common in adults.[4] Swallowed objects are more likely to lodge in the esophagus or stomach than in the pharynx or duodenum.[5]

Diagnosis

If the person who swallowed the foreign body is doing well, usually an x-ray image will be taken which will show any metal objects, and this will be repeated a few days later to confirm that the object has passed all the way through the digestive system. Also it needs to be confirmed that the object is not stuck in the airways, in the bronchial tree.

Abdominal X-ray showing small packages of cocaine swallowed by a trafficker.

Abdominal X-ray showing small packages of cocaine swallowed by a trafficker. Vibrator stuck in the rectum can be seen on this abdominal X-ray.

Vibrator stuck in the rectum can be seen on this abdominal X-ray. Chest radiograph showing a Venezuelan 25 cent coin lodged in the upper esophagus of a 9-year-old girl.

Chest radiograph showing a Venezuelan 25 cent coin lodged in the upper esophagus of a 9-year-old girl. A coin seen on AP CXR in the esophagus

A coin seen on AP CXR in the esophagus A coin seen on lateral CXR in the esophagus

A coin seen on lateral CXR in the esophagus Fishbone pierced in the upper esophagus.Left image during swallowing contrast medium, right image after swallow only dimly visible.

Fishbone pierced in the upper esophagus.Left image during swallowing contrast medium, right image after swallow only dimly visible.

Treatment

Most objects that are swallowed will, if they have passed the pharynx, pass all the way through the gastrointestinal tract unaided.[6] However, sometimes an object becomes arrested (usually in the terminal ileum or the rectum) or a sharp object penetrates the bowel wall. If the foreign body causes problems like pain, vomiting or bleeding it must be removed.

Swallowed batteries can be associated with additional damage,[7][8] with mercury poisoning (from mercury batteries) and lead poisoning (from lead batteries) presenting important risks.

While swallowed coins typically traverse the alimentary tract without further incident, care must be taken to monitor patients, as reaction of the metals in the coin with gastric acid and other digestive juices may produce various toxic compounds if the coin remains within the alimentary tract for a prolonged period of time.[9]

Endoscopic foreign body retrieval is the first-line treatment for removal of a foreign body from the alimentary tract.[10]

Glucagon has been used to treat esophageal foreign bodies, with the intent that it relaxes the smooth muscle of the lower esophageal spincter to allow the foreign body to pass into the stomach.[10] However, evidence does not support a benefit of treatment with glucagon, and its use may result in side effects.[11]

See also

- 101 Things Removed from the Human Body, 2003 British documentary detailing unusual foreign objects located and removed from patients

- Bezoar

- Rectal foreign body

References

- ↑ "Pediatrics, Foreign Body Ingestion: Overview - eMedicine". Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Koornstra JJ, Weersma RK (July 2008). "Management of rectal foreign bodies: description of a new technique and clinical practice guidelines". World J. Gastroenterol. 14 (27): 4403–6. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4403. PMC 2731197. PMID 18666334. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19.

- ↑ Arana A, Hauser B, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Vandenplas Y (August 2001). "Management of ingested foreign bodies in childhood and review of the literature". Eur. J. Pediatr. 160 (8): 468–72. doi:10.1007/s004310100788. PMID 11548183. S2CID 7550183. Archived from the original on 2001-11-22. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Conway WC, Sugawa C, Ono H, Lucas CE (March 2007). "Upper GI foreign body: an adult urban emergency hospital experience". Surg Endosc. 21 (3): 455–60. doi:10.1007/s00464-006-9004-z. PMID 17131048. S2CID 30134627.

- ↑ Li ZS, Sun ZX, Zou DW, Xu GM, Wu RP, Liao Z (October 2006). "Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper-GI tract: experience with 1088 cases in China". Gastrointest. Endosc. 64 (4): 485–92. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.059. PMID 16996336.

- ↑ Lin CH, Chen AC, Tsai JD, Wei SH, Hsueh KC, Lin WC (September 2007). "Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies in children". Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 23 (9): 447–52. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70052-4. PMID 17766213.

- ↑ "Battery Ingestion". Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Yardeni D, Yardeni H, Coran AG, Golladay ES (July 2004). "Severe esophageal damage due to button battery ingestion: can it be prevented?" (PDF). Pediatr. Surg. Int. 20 (7): 496–501. doi:10.1007/s00383-004-1223-6. hdl:2027.42/47164. PMID 15221361. S2CID 2672727.

- ↑ Puig, S.; Scharitzer, M.; Cengiz, K.; Jetzinger, E.; Rupprecht, L. (2004-09-01). "Effects of gastric acid on euro coins: chemical reaction and radiographic appearance after ingestion by infants and children". Emergency Medicine Journal. 21 (5): 553–556. doi:10.1136/emj.2002.004879. ISSN 1472-0205. PMC 1726428. PMID 15333527.

- 1 2 Grimes, Ian; Pfau, Patrick R. (2011). "Ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions". In Ginsberg, Gregory G.; Kochman, Michael L.; Norton, Ian D.; Gostout, Christopher J. (eds.). Clinical Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (2nd ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 232. ISBN 9781437735703.

- ↑ Peksa, Gary D.; DeMott, Joshua M.; Slocum, Giles W.; Burkins, Jaxson; Gottlieb, Michael (April 2019). "Glucagon for relief of acute esophageal foreign bodies and food impactions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis". Pharmacotherapy. 39 (4): 463–472. doi:10.1002/phar.2236. PMID 30779190. S2CID 73457663.