Glucagon

Glucagon ball and stick model, with the carboxyl terminus above and the amino terminus below | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | GlucaGen, Baqsimi, Gvoke, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Glycogenolytic[1] |

| Main uses | Low blood sugar, beta blocker overdose, calcium channel blocker overdose, anaphylaxis who do not improve with epinephrine[1] |

| Side effects | Vomiting, low blood potassium, low blood pressure[2][1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | Nasal, intravenous (IV), intramuscular injection (IM), subcutaneous injection |

| Defined daily dose | 1 mg[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682480 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C153H225N43O49S |

| Molar mass | 3482.747314 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Glucagon is a medication and hormone.[2] As a medication it is used to treat low blood sugar, beta blocker overdose, calcium channel blocker overdose, and those with anaphylaxis who do not improve with epinephrine.[1] It is given by injection into a vein, muscle, or under the skin.[1] A version given in the nose is also available.[6]

Common side effects include vomiting.[1] Other side effects include low blood potassium and low blood pressure.[2] It is not recommended in people who have a pheochromocytoma or insulinoma.[1] Use in pregnancy has not be found to be harmful to the baby.[7] Glucagon is in the glycogenolytic family of medications.[1] It works by causing the liver to break down glycogen into glucose.[1]

Glucagon was approved for medical use in the United States in 1960.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$25.75 a dose.[9] In the United Kingdom that dose costs the NHS about £11.52.[2] In the United States the wholesale cost of a dose is US$247.32.[10] It is a manufactured form of the glucagon hormone.[1]

Medical uses

Low blood sugar

An injectable form of glucagon may be used in low blood sugar when the person is unconscious or for other reasons cannot take glucose by mouth or by intravenous. The glucagon is given by intramuscular, intravenous or subcutaneous injection, and quickly raises blood glucose levels. To use the injectable form, it must be reconstituted prior to use, a step that requires a sterile diluent to be injected into a vial containing powdered glucagon, because the hormone is highly unstable when dissolved in solution. When dissolved in a fluid state, glucagon can form amyloid fibrils, or tightly woven chains of proteins made up of the individual glucagon peptides, and once glucagon begins to fibrilize, it becomes useless when injected, as the glucagon cannot be absorbed and used by the body. The reconstitution process makes using glucagon cumbersome, although there are a number of products now in development from a number of companies that aim to make the product easier to use.

Beta blocker overdose

Some evidence suggests a benefit of higher doses of glucagon in the treatment of beta blocker overdose; the likely mechanism of action is the increase of cAMP in the myocardium, in effect bypassing the β-adrenergic second messenger system.[11]

Anaphylaxis

Some people who have anaphylaxis and are on beta blockers are resistant to epinephrine. In this situation glucagon intravenously may be useful to treat their low blood pressure.[12]

Impacted food bolus

Glucagon has been used in those with an impacted food bolus in the esophagus.[13] There is little evidence for effectiveness in this condition,[14][15][16] and glucagon may induce nausea and vomiting,[16] but considering the safety of glucagon this is still considered an acceptable option as long it does not lead to delays in arranging other treatments.[17][18]

ERCP

Glucagon's effect of increasing cAMP causes relaxation of splanchnic smooth muscle, allowing cannulation of the duodenum during the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedure.

Dosage

In anaphylaxis it may be used at an initial dose of 20 to 30 ug/kg to a maximum of 1 mg followed by an infusion at 5 to 15 ug per minute.[19]

The defined daily dose is 1 mg by injection.[4]

Side effects

Glucagon acts very quickly; common side-effects include headache and nausea.

Drug interactions: Glucagon interacts only with oral anticoagulants, increasing the tendency to bleed.[20]

Contraindications

While glucagon can be used clinically to treat various forms of hypoglycemia, it is contraindicated in patients with pheochromocytoma, as it can induce the tumor to release catecholamines, leading to a sudden elevation in blood pressure.[21] Likewise, glucagon is contraindicated in patients with an insulinoma, as its hyperglycemic effect can induce the tumor to release insulin, leading to rebound hypoglycemia.[21]

Mechanism of action

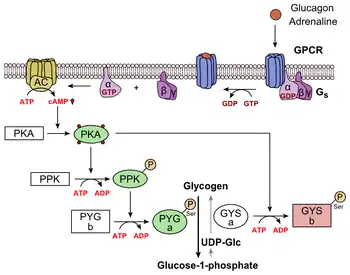

Glucagon binds to the glucagon receptor, a G protein-coupled receptor, located in the plasma membrane. The conformation change in the receptor activates G proteins, a heterotrimeric protein with α, β, and γ subunits. When the G protein interacts with the receptor, it undergoes a conformational change that results in the replacement of the GDP molecule that was bound to the α subunit with a GTP molecule. This substitution results in the releasing of the α subunit from the β and γ subunits. The alpha subunit specifically activates the next enzyme in the cascade, adenylate cyclase.

Adenylate cyclase manufactures cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cyclic AMP or cAMP), which activates protein kinase A (cAMP-dependent protein kinase). This enzyme, in turn, activates phosphorylase kinase, which then phosphorylates glycogen phosphorylase b, converting it into the active form called phosphorylase a. Phosphorylase a is the enzyme responsible for the release of glucose-1-phosphate from glycogen polymers.

Additionally, the coordinated control of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in the liver is adjusted by the phosphorylation state of the enzymes that catalyze the formation of a potent activator of glycolysis called fructose-2,6-bisphosphate.[22] The enzyme protein kinase A that was stimulated by the cascade initiated by glucagon will also phosphorylate a single serine residue of the bifunctional polypeptide chain containing both the enzymes fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase and phosphofructokinase-2. This covalent phosphorylation initiated by glucagon activates the former and inhibits the latter. This regulates the reaction catalyzing fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (a potent activator of phosphofructokinase-1, the enzyme that is the primary regulatory step of glycolysis)[23] by slowing the rate of its formation, thereby inhibiting the flux of the glycolysis pathway and allowing gluconeogenesis to predominate. This process is reversible in the absence of glucagon (and thus, the presence of insulin).

Glucagon stimulation of PKA also inactivates the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase.[24]

History

In the 1920s, Kimball and Murlin studied pancreatic extracts, and found an additional substance with hyperglycemic properties. They described glucagon in 1923.[25] The amino acid sequence of glucagon was described in the late 1950s.[26] A more complete understanding of its role in physiology and disease was not established until the 1970s, when a specific radioimmunoassay was developed.

A nasal version was approved for use in the United States and Canada in 2019.[27][28][29][30][31]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Glucagon". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 487. ISBN 9780857111562.

- 1 2 "Glucagon Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ↑ "GlucaGen Hypokit 1 mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 15 June 2015. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (24 March 2020). "FDA approves first treatment for severe hypoglycemia that can be administered without an injection". FDA. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ "Glucagon (GlucaGen) Use During Pregnancy". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Glucagon". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "NADAC as of 2016-12-21 | Data.Medicaid.gov". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ↑ White CM (May 1999). "A review of potential cardiovascular uses of intravenous glucagon administration". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 39 (5): 442–7. PMID 10234590.

- ↑ Tang AW (October 2003). "A practical guide to anaphylaxis". American Family Physician. 68 (7): 1325–32. PMID 14567487.

- ↑ Ko HH, Enns R (October 2008). "Review of food bolus management". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 22 (10): 805–8. doi:10.1155/2008/682082. PMC 2661297. PMID 18925301.

- ↑ Arora S, Galich P (March 2009). "Myth: glucagon is an effective first-line therapy for esophageal foreign body impaction". Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 11 (2): 169–71. doi:10.1017/s1481803500011143. PMID 19272219.

- ↑ Leopard D, Fishpool S, Winter S (September 2011). "The management of oesophageal soft food bolus obstruction: a systematic review". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 93 (6): 441–4. doi:10.1308/003588411X588090. PMC 3369328. PMID 21929913.

- 1 2 Weant KA, Weant MP (April 2012). "Safety and efficacy of glucagon for the relief of acute esophageal food impaction". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 69 (7): 573–7. doi:10.2146/ajhp100587. PMID 22441787.

- ↑ Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher LR, Fukami N, Harrison ME, Jain R, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Maple JT, Sharaf R, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA (June 2011). "Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions" (PDF). Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 73 (6): 1085–1091. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.010. PMID 21628009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2013.

- ↑ Chauvin A, Viala J, Marteau P, Hermann P, Dray X (July 2013). "Management and endoscopic techniques for digestive foreign body and food bolus impaction". Digestive and Liver Disease. 45 (7): 529–42. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2012.11.002. PMID 23266207.

- ↑ Society, Canadian Paediatric. "Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis in infants and children | Canadian Paediatric Society". cps.ca. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ↑ Koch-Weser J (March 1970). "Potentiation by glucagon of the hypoprothrombinemic action of warfarin". Annals of Internal Medicine. 72 (3): 331–5. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-72-3-331. PMID 5415418.

- 1 2 "Information for the Physician: Glucagon for Injection (rDNA origin)" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ↑ Hue L, Rider MH (July 1987). "Role of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate in the control of glycolysis in mammalian tissues". The Biochemical Journal. 245 (2): 313–24. doi:10.1042/bj2450313. PMC 1148124. PMID 2822019.

- ↑ Claus TH, El-Maghrabi MR, Regen DM, Stewart HB, McGrane M, Kountz PD, Nyfeler F, Pilkis J, Pilkis SJ (1984). The role of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate in the regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Current Topics in Cellular Regulation. Vol. 23. pp. 57–86. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-152823-2.50006-4. ISBN 9780121528232. PMID 6327193.

- ↑ Feliú JE, Hue L, Hers HG (August 1976). "Hormonal control of pyruvate kinase activity and of gluconeogenesis in isolated hepatocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 73 (8): 2762–6. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.2762F. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.8.2762. PMC 430732. PMID 183209.

- ↑ Kimball C, Murlin J (1923). "Aqueous extracts of pancreas III. Some precipitation reactions of insulin". J. Biol. Chem. 58 (1): 337–348. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ↑ Bromer W, Winn L, Behrens O (1957). "The amino acid sequence of glucagon V. Location of amide groups, acid degradation studies and summary of sequential evidence". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79 (11): 2807–2810. doi:10.1021/ja01568a038.

- ↑ "FDA approves first treatment for severe hypoglycemia that can be administered without an injection". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 24 July 2019. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Baqsimi". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 25 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ "Ready for rescue: new nasally administered glucagon for severe hypoglycemia approved in Canada!". Diabetes Canada. 12 December 2019. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ "GLUCAGON NASAL POWDER (BAQSIMI — ELI LILLY CANADA INC)" (PDF). CADTH. 22 January 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ↑ "glucagon". CADTH.ca. 25 June 2019. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Glucagon". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Glucagon hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Glucagon Nasal Powder". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.