Heat exhaustion

| Heat exhaustion | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Heat stress[1] | |

| |

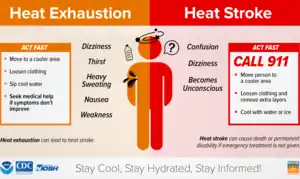

| Differentiation between heat exhaustion and heat stroke | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Headache, nausea, lightheadedness, sweating, increased body temperature[2] |

| Complications | Heat stroke[3] |

| Causes | High temperatures with not enough fluids[3] |

| Risk factors | Older age, high blood pressure, intense exercise[2][1] |

| Treatment | Moving to a cool environment, drinking fluids, putting cool water on the body[2] |

| Frequency | 4 per 10,000 ER visits (USA)[4] |

Heat exhaustion is the body’s response to an excessive loss of water and salt, usually through excessive sweating.[2] Symptoms include headache, nausea, lightheadedness, sweating, and increased body temperature but not more than 40.5°C (104°F).[2][1] Onset may be rapid or over several days.[5][2] Without treatment, heat stroke may occur.[3]

The cause is typically being in high temperatures with not enough fluids.[3] Risk factors include older age, younger, high blood pressure, and intense exercise.[2][1][5] It is a type of heat illness of moderate severity.[2][5] Unlike heat stroke, it is not associated with confusion.[4]

Management involves moving to a cool environment, drinking cool fluids, and putting cool water on the body.[2] Exercise should be stopped and direct sun exposure should be avoided.[5] Assessment in an emergency department is recommended.[4] Heat acclimatization and fitness training can decrease the risk.[5]

Heat exhaustion affects millions of people a year.[5] It represents about 4 per 10,000 emergency department visits in the United States.[4] Heat illness is predicted to become significantly more common over the next few decades.[5] Recommended planning for heat waves, including the availability of air conditioned spaces, is recommended.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of heat exhaustion include skin tingling, nausea, dizziness, irritability, headache, thirst, weakness, vomiting, high body temperature, excessive sweating, pupil dilation, and decreased urine output.[6]

Causes

Common risk factors include:[7]

- Hot, sunny, humid weather

- Physical exertion, especially in hot, humid weather

- Due to impaired thermoregulation, elderly people and infants can get serious heat illness even at rest, if the weather outside is hot and humid, and they are not getting enough cool air.

- Some drugs, such as diuretics, antihistamines, beta-blockers, alcohol, MDMA ('Ecstasy', 'Molly'), and other amphetamines can cause an increase in the risk of heat exhaustion.[8]

Especially during physical exertion, risk factors for heat exhaustion include:[7]

- Wearing dark, padded, or insulated clothing; hats; and/or helmets (for example, football pads, turnout gear, etc.)

- Having a higher percentage of body fat

- Dehydration

- Fever

- Some medications, like beta blockers and antipsychotic medicines[8]

Diagnosis

The evaluation of an individual with heat exhaustion is consistent with the following:[9]

- Physical exam

- CBC

- EKG

- Urinalysis

Treatment

First aid for heat exhaustion includes:[6][8]

- Moving the person to a cool place

- Having the patient take off extra layers of clothes

- Cooling the patient down by fanning them and/or putting wet towels on their body

- Having them lie down and put their feet up if they are feeling dizzy

- Having them drink water or "sports drinks" unless they are unconscious, too disoriented to drink, or vomiting

- Turning the patient on their side if they are vomiting

Other measures may include:[10]

- Provide supplemental oxygen

- Administer intravenous fluids and electrolytes if they are too confused to drink or are vomiting

Prognosis

If left untreated, heat exhaustion may progress to heat stroke.[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Leiva, DF; Church, B (January 2022). "Heat Illness". PMID 31971756.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Heat Stress Related Illness | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 18 May 2022. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Heat Illness". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Gauer, R; Meyers, BK (15 April 2019). "Heat-Related Illnesses". American family physician. 99 (8): 482–489. PMID 30990296.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kenny, Glen P.; Wilson, Thad E.; Flouris, Andreas D.; Fujii, Naoto (2018). "Heat exhaustion". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 157: 505–529. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64074-1.00031-8. PMID 30459023.

- 1 2 3 Jacklitsch, Brenda L. (June 29, 2011). "Summer Heat Can Be Deadly for Outdoor Workers". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- 1 2 "Heat Injury and Heat Exhaustion". www.orthoinfo.aaos.org. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. July 2009. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Heat Exhaustion and Heatstroke". www.nhs.uk. National Health Service of the United Kingdom. June 11, 2015. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ↑ Leiva, Daniel F.; Church, Ben (2023). "Heat Illness". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- ↑ Mistovich, Joseph J.; Karren, Keith J.; Hafen, Brent (July 18, 2013). Prehospital Emergency Care (10 ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0133369137.