High-frequency ventilation

| High-frequency ventilation | |

|---|---|

| MeSH | D006612 |

High-frequency ventilation is a type of mechanical ventilation which utilizes a respiratory rate greater than four times the normal value.[1] (>150 (Vf) breaths per minute) and very small tidal volumes.[2][3] High frequency ventilation is thought to reduce ventilator-associated lung injury (VALI), especially in the context of ARDS and acute lung injury.[2] This is commonly referred to as lung protective ventilation.[4] There are different types of high-frequency ventilation.[2] Each type has its own unique advantages and disadvantages. The types of HFV are characterized by the delivery system and the type of exhalation phase.

High-frequency ventilation may be used alone, or in combination with conventional mechanical ventilation. In general, those devices that need conventional mechanical ventilation do not produce the same lung protective effects as those that can operate without tidal breathing. Specifications and capabilities will vary depending on the device manufacturer.

Physiology

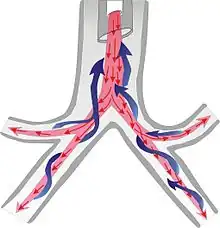

With conventional ventilation where tidal volumes (VT) exceed dead space(VDEAD), gas exchange is largely related to bulk flow of gas to the alveoli. With high-frequency ventilation, the tidal volumes used are smaller than anatomical and equipment dead space and therefore alternative mechanisms of gas exchange occur.

Procedure

- Supraglottic Approach—The supraglottic approach is advantageous as it allows a completely tubeless surgical field.

- Subglottic Approach

- Transtracheal Approach

High-frequency jet ventilation (passive)

In the UK, the Mistral or Monsoon jet ventilator (Acutronic Medical Systems) is most commonly used. In the United States the Bunnell LifePulse jet ventilator is most commonly used.

HFJV minimizes movement of the thorax and abdomen and facilitates surgical procedures where even slight motion artifact from spontaneous or intermittent positive pressure ventilation may significantly affect the duration and success of the procedure (for example atrial fibrillation ablation). HFJV does NOT allow: setting specific tidal volume, sampling ETCO2 (and because of this, frequent ABGs are required to measure PaCO2). In HFJV a jet is applied with a set driving pressure, followed by passive exhalation for a very short period before the next jet is delivered, creating "auto-PEEP" (called pause pressure by the jet ventilator).[3] The risk of excessive breath-stacking leading to barotrauma and pneumothorax is low but not zero.

In HFJV exhalation is passive (depends on passive lung and chest-wall recoil) whereas in HFOV gas movement is caused by in-and-out movement of the “loudspeaker” oscillator membrane. Thus in HFOV both inspiration and expiration are actively caused by the oscillator, and passive exhalation is not allowed.

Bunnell LifePulse jet ventilator

_Delivery_with_High-frequency_Jet_Ventilation_(HFJV).jpg.webp)

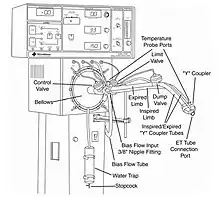

High-frequency jet ventilation (HFJV) is provided by the Bunnell Life Pulse High-Frequency Ventilator. HFJV employs an endotracheal tube adaptor in place for the normal 15 mm ET tube adaptor. A high pressure "jet" of gas flows out of the adaptor and into the airway. This jet of gas occurs for a very brief duration, about 0.02 seconds, and at high-frequency: 4-11 hertz. Tidal volumes ≤ 1 ml/Kg are used during HFJV. This combination of small tidal volumes delivered for very short periods of time creates the lowest possible distal airway and alveolar pressures produced by a mechanical ventilator. Exhalation is passive. Jet ventilators utilize various I:E ratios—between 1:1.1 and 1:12—to help achieve optimal exhalation. Conventional mechanical breaths are sometimes used to aid in reinflating the lung. Optimal PEEP is used to maintain alveolar inflation and promote ventilation-to-perfusion matching. Jet ventilation has been shown to reduce ventilator induced lung injury by as much as 20%. Usage of high-frequency jet ventilation is recommended in neonates and adults with severe lung injury.[5]

Indications for use

The Bunnell Life Pulse High-Frequency Ventilator is indicated for use in ventilating critically ill infants with pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE). Infants studied ranged in birth weight from 750 to 3529 grams and in gestation age from 24 to 41 weeks.

The Bunnell Life Pulse High-Frequency Ventilator is also indicated for use in ventilating critically ill infants with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) complicated by pulmonary air leaks who are, in the opinion of their physicians, failing on conventional ventilation. Infants of this description studied ranged in birth weight from 600 to 3660 grams and in gestational age from 24 to 38 weeks.

Adverse effects

The adverse side effects noted during the use of high-frequency ventilation include those commonly found during the use of conventional positive pressure ventilators. These adverse effects include:

Contraindications

High-frequency jet ventilation is contraindicated in patients requiring tracheal tubes smaller than 2.5 mm ID.

Settings and parameters

Settings that can be adjusted in HFJV include 1) inspiratory time, 2) driving pressure, 3) frequency, 4) FiO2, and 5) humidity. Increases in FiO2, inspiratory time, and frequency improve oxygenation (by increasing "auto-PEEP" or pause pressure), while an increase in driving pressure and a decrease in frequency improve ventilation.

Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP)

The peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) window displays the average PIP. During startup a PIP sample is taken with every inhalation cycle and is averaged with all other samples taken over the most recent ten-second period. After regular operation begins, samples are averaged over the most recent twenty-second period.

ΔP (Delta P)

The value displayed in the ΔP (pressure difference) window represents the difference between the PIP value and the PEEP value.

Servo pressure

The servo pressure display indicates the amount of pressure the machine must generate internally in order to achieve the PIP appearing in the servo-display. Its value can range from 0—20 psi (0—137.9 kPa). If the PIP sensed or approximated at the distal tip of the tracheal tube deviates from the desired PIP, the machine automatically generates more or less internal pressure in an attempt to compensate for the change. The servo-pressure display keeps the operator informed.

The servo display is a general clinical indicator of changes in the compliance or resistance of the patient's lungs, as well as loss of lung volume due to tension pneumothorax.

High-frequency oscillatory ventilation

In HFOV the airway is pressurized to a set mean airway pressure (called continuous lung-distending pressure) through an adjustable expiratory valve. Small pressure oscillations delivered at a very high rate are superimposed by the action of a “loudspeaker” oscillator membrane. HFOV is often used in premature neonates with respiratory distress syndrome who fail to oxygenate appropriately with lung-protective settings of conventional ventilation. It has also been used in ARDS in adults, but two studies (the OSCAR and OSCILLATE trials) showed negative results for this indication.

Parameters that can be set in HFOV includes the continuous lung-distending pressure, oscillation amplitude and frequency, I:E ratio (positive-oscillation/negative-oscillation ratio), fresh gas flow (called bias flow), and FiO2. Increases in continuous lung-distending pressure and FiO2 will improve oxygenation. Increases in amplitude or fresh gas flow and decreases in frequency will improve ventilation.

High-frequency percussive ventilation

HFPV — High-frequency percussive ventilation combines HFV plus time cycled, pressure-limited controlled mechanical ventilation (i.e., pressure control ventilation, PCV).

High-frequency positive pressure ventilation

HFPPV — High-frequency positive pressure ventilation is rarely used anymore, having been replaced by high-frequency jet, oscillatory and percussive types of ventilation. HFPPV is delivered through the endotracheal tube using a conventional ventilator whose frequency is set near its upper limits. HFPV began to be used in selected centres in the 1980s. It is a hybrid of conventional mechanical ventilation and high-frequency oscillatory ventilation. It has been used to salvage patients with persistent hypoxemia when on conventional mechanical ventilation or, in some cases, used as a primary modality of ventilatory support from the start.[6][7]

High-frequency flow interruption

HFFI — High Frequency Flow Interruption is similar to high-frequency jet ventilation but the gas control mechanism is different. Frequently a rotating bar or ball with a small opening is placed in the path of a high pressure gas. As the bar or ball rotates and the opening lines-up with the gas flow, a small, brief pulse of gas is allowed to enter the airway. Frequencies for HFFI are typically limited to maximum of about 15 hertz.

High-frequency ventilation (active)

High-frequency ventilation (active) — HFV-A is notable for the active exhalation mechanic included. Active exhalation means a negative pressure is applied to force volume out of the lungs. The CareFusion 3100A and 3100B are similar in all aspects except the target patient size. The 3100A is designed for use on patients up to 35 kilograms and the 3100B is designed for use on patients larger than 35 kilograms.

CareFusion 3100A and 3100B

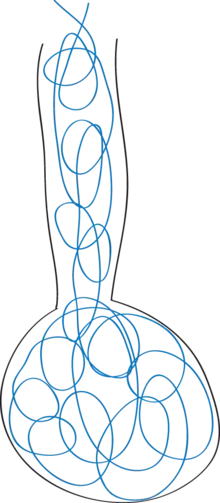

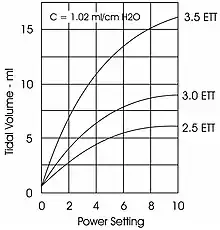

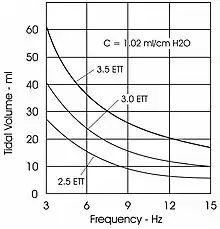

High-frequency oscillatory ventilation was first described in 1972[8] and is used in neonates and adult patient populations to reduce lung injury, or to prevent further lung injury.[9] HFOV is characterized by high respiratory rates between 3.5 and 15 hertz (210 - 900 breaths per minute) and having both inhalation and exhalation maintained by active pressures. The rates used vary widely depending upon patient size, age, and disease process. In HFOV the pressure oscillates around the constant distending pressure (equivalent to mean airway pressure [MAP]) which in effect is the same as positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Thus gas is pushed into the lung during inspiration, and then pulled out during expiration. HFOV generates very low tidal volumes that are generally less than the dead space of the lung. Tidal volume is dependent on endotracheal tube size, power and frequency. Different mechanisms (direct bulk flow - convective, Taylorian dispersion, Pendelluft effect, asymmetrical velocity profiles, cardiogenic mixing and molecular diffusion) of gas transfer are believed to come into play in HFOV compared to normal mechanical ventilation. It is often used in patients who have refractory hypoxemia that cannot be corrected by normal mechanical ventilation such as is the case in the following disease processes: severe ARDS, ALI and other oxygenation diffusion issues. In some neonatal patients HFOV may be used as the first-line ventilator due to the high susceptibility of the premature infant to lung injury from conventional ventilation.

Breath delivery

The vibrations are created by an electromagnetic valve that controls a piston. The resulting vibrations are similar to those produced by a stereo speaker. The height of the vibrational wave is the amplitude. Higher amplitudes create greater pressure fluctuations which move more gas with each vibration. The number of vibrations per minute is the frequency. One Hertz equals 60 cycles per minute. The higher amplitudes at lower frequencies will cause the greatest fluctuation in pressure and move the most gas.

Altering the % inspiratory time (T%i) changes the proportion of the time in which the vibration or sound wave is above the baseline versus below it. Increasing the % Inspiratory Time will also increase the volume of gas moved or tidal volume. Decreasing the frequency, increasing the amplitude, and increasing the % inspiratory time will all increase tidal volume and eliminate CO2. Increasing the tidal volume will also tend to increase the mean airway pressure.

Settings and measurements

Bias flow

The bias flow controls and indicates the rate of continuous flow of humidified blended gas through the patient circuit. The control knob is a 15-turn pneumatic valve which increases flow as it is turned.

Mean pressure adjust

The mean pressure adjust setting adjusts the mean airway pressure (PAW) by controlling the resistance of the airway pressure control valve. The mean airway pressure will change and requires the mean pressure adjust to be adjusted when the following settings are changed:

- Frequency (Hertz)

- % Inspiratory time

- Power and Δp change

- Piston centering

During high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV), PAW is the primary variable affecting oxygenation and is set independent of other variables on the oscillator. Because distal airway pressure changes during HFOV are minimal,[10][11] the PAW during HFOV can be viewed in a manner similar to the PEEP level in conventional ventilation.[12] The optimal PAW can be considered as a compromise between maximal lung recruitment and minimal overdistention.

Mean pressure limit

The mean pressure limit controls the limit above which proximal PAW cannot be increased by setting the control pressure of the pressure limit valve. The mean pressure limit range is 10-45 cmH2O.

ΔP and amplitude

The power setting is set as amplitude to establish a measured change of pressure (ΔP). Amplitude/Power is a setting which determines the amount of power that is driving the oscillator piston forward and backward resulting in an air volume (tidal volume) displacement. The effect of the amplitude on the ΔP that it is changed by the displacement of the oscillator piston and hence the oscillatory pressure (ΔP). The power setting interacts with PAW conditions existing within the patient circuit to produce the resulting ΔP.

% Inspiratory time

The percent of inspiratory time is a setting which determines the percent of cycle time the piston is traveling toward (or at its final inspiratory position). The inspiratory percent range is 30—50%.

Frequency

The frequency setting is measured in hertz (hz). The control knob is a 10-turn clockwise-increasing potentiometer covering a range of 3 Hz to 15 Hz. The set frequency is displayed on a digital meter on the face of the ventilator. One Hertz is (-/+5%) equal to 1 breath per second, or 60 breaths per minute (e.g., 10 Hz = 600 breaths per minute). Changes in frequency are inversely proportional to the amplitude and thus delivered tidal volume.

- Breaths per minute (f)

Oscillation trough pressure

Oscillation trough pressure is the instantaneous pressure within the HFOV circuit following the oscillating piston reaching its complete negative deflection.

Transtracheal jet ventilation

Transtracheal jet ventilation refers to a type of high-frequency ventilation, low tidal volume ventilation provided via a laryngeal catheter by specialized ventilators that are usually only available in the operating room or intensive care unit. This procedure is occasionally employed in the operating room when a difficult airway is anticipated. Such as Treacher Collins syndrome, Robin sequence, head and neck surgery with supraglottic or glottic obstruction).[13][14][15][16]

Adverse effects

The adverse side effects noted during the use of high-frequency ventilation include those commonly found during the use of conventional positive pressure ventilators. These adverse effects include:

See also

References

- ↑ BRISCOE WA, FORSTER RE, COMROE JH (1954). "Alveolar ventilation at very low tidal volumes". J Appl Physiol. 7 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1152/jappl.1954.7.1.27. PMID 13174467.

- 1 2 3 Krishnan JA, Brower RG (2000). "High-frequency ventilation for acute lung injury and ARDS". Chest. 118 (3): 795–807. doi:10.1378/chest.118.3.795. PMID 10988205. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06.

- 1 2 Standiford TJ, Morganroth ML (December 1989). "High-frequency ventilation". Chest. 96 (6): 1380–9. doi:10.1378/chest.96.6.1380. PMID 2510975.

- ↑ Bollen CW, Uiterwaal CS, van Vught AJ (February 2006). "Systematic review of determinants of mortality in high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome". Crit Care. 10 (1): R34. doi:10.1186/cc4824. PMC 1550858. PMID 16507163.

- ↑ D. P. Schuster; M. Klain; J. V. Snyder (October 1982). "Comparison of high-frequency jet ventilation to conventional ventilation during severe acute respiratory failure in humans". Critical Care Medicine. 10 (10): 625–630. doi:10.1097/00003246-198210000-00001. PMID 6749433.

- ↑ Eastman A, Holland D, Higgins J, Smith B, Delagarza J, Olson C, Brakenridge S, Foteh K, Friese R (August 2006). "High-frequency percussive ventilation improves oxygenation in trauma patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective review". American Journal of Surgery. 192 (2): 191–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.021. PMID 16860628.

- ↑ Rimensberger PC (October 2003). "ICU cornerstone: high-frequency ventilation is here to stay". Critical Care. 7 (5): 342–4. doi:10.1186/cc2327. PMC 270713. PMID 12974963.

- ↑ Lunkenheimer PP, Rafflenbeul W, Keller H, Frank I, Dickhut HH, Fuhrmann C (1972). "Application of transtracheal pressure oscillations as a modification of "diffusing respiration"". Br J Anaesth. 44 (6): 627–628. doi:10.1093/bja/44.6.627. PMID 5045565.

- ↑ P. Fort; C. Farmer; J. Westerman; J. Johannigman; W. Beninati; S. Dolan; S. Derdak (June 1997). "High-frequency oscillatory ventilation for adult respiratory distress syndrome--a pilot study". Critical Care Medicine. 25 (6): 937–947. doi:10.1097/00003246-199706000-00008. PMID 9201044.

- ↑ Gerstmann DR, Fouke JM, Winter DC, Taylor AF, deLemos RA (October 1990). "Proximal, tracheal, and alveolar pressures during high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in a normal rabbit model". Pediatric Research. 28 (4): 367–73. doi:10.1203/00006450-199010000-00013. PMID 2235135.

- ↑ Easley RB, Lancaster CT, Fuld MK, et al. (January 2009). "Total and regional lung volume changes during high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) of the normal lung". Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 165 (1): 54–60. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2008.10.010. PMC 2637463. PMID 18996228.

- ↑ Ono K, Koizumi T, Nakagawa R, Yoshikawa S, Otagiri T (2009). "Comparisons of different mean airway pressure settings during high-frequency oscillation in inflammatory response to oleic acid-induced lung injury in rabbits". Journal of Inflammation Research. 2: 21–8. doi:10.2147/jir.s4491. PMC 3218723. PMID 22096349.

- ↑ Ravussin P, Bayer-Berger M, Monnier P, Savary M, Freeman J (1987). "Percutaneous transtracheal ventilation for laser endoscopic procedures in infants and small children with laryngeal obstruction: report of two cases". Can J Anaesth. 34 (1): 83–6. doi:10.1007/BF03007693. PMID 3829291.

- ↑ Benumof JL, Scheller MS (1989). "The importance of transtracheal jet ventilation in the management of the difficult airway". Anesthesiology. 71 (5): 769–78. doi:10.1097/00000542-198911000-00023. PMID 2683873.

- ↑ Weymuller EA, Pavlin EG, Paugh D, Cummings CW (1987). "Management of difficult airway problems with percutaneous transtracheal ventilation". Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 96 (1 Pt 1): 34–7. doi:10.1177/000348948709600108. PMID 3813383.

- ↑ Boyce JR, Peters GE, Carroll WR, Magnuson JS, McCrory A, Boudreaux AM (2005). "Preemptive vessel dilator cricothyrotomy aids in the management of upper airway obstruction". Can J Anaesth. 52 (7): 765–9. doi:10.1007/BF03016567. PMID 16103392.