Hydrazoic acid

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Hydrogen azide | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.059 |

| EC Number |

|

Gmelin Reference |

773 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

HN3 |

| Molar mass | 43.03 g/mol |

| Appearance | colorless, highly volatile liquid |

| Density | 1.09 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −80 °C (−112 °F; 193 K) |

| Boiling point | 37 °C (99 °F; 310 K) |

Solubility in water |

highly soluble |

| Solubility | soluble in alkali, alcohol, ether |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.6 [1] |

| Conjugate base | Azide |

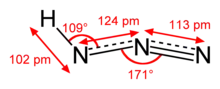

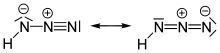

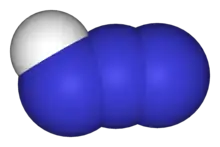

| Structure | |

Molecular shape |

approximately linear |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Highly toxic, explosive, reactive |

| GHS labelling: | |

Pictograms |

|

Signal word |

Danger |

Hazard statements |

H200, H319, H335, H370 |

Precautionary statements |

P201, P202, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P280, P281, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P307+P311, P312, P321, P337+P313, P372, P373, P380, P401, P403+P233, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations |

Sodium azide |

Related nitrogen hydrides |

Ammonia Hydrazine |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Hydrazoic acid, also known as hydrogen azide or azoimide,[2] is a compound with the chemical formula HN3.[3] It is a colorless, volatile, and explosive liquid at room temperature and pressure. It is a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen, and is therefore a pnictogen hydride. It was first isolated in 1890 by Theodor Curtius.[4] The acid has few applications, but its conjugate base, the azide ion, is useful in specialized processes.

Hydrazoic acid, like its fellow mineral acids, is soluble in water. Undiluted hydrazoic acid is dangerously explosive[5] with a standard enthalpy of formation ΔfHo (l, 298K) = +264 kJmol−1.[6] When dilute, the gas and aqueous solutions (<10%) can be safely handled.

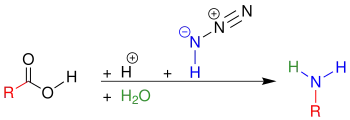

Production

The acid is usually formed by acidification of an azide salt like sodium azide. Normally solutions of sodium azide in water contain trace quantities of hydrazoic acid in equilibrium with the azide salt, but introduction of a stronger acid can convert the primary species in solution to hydrazoic acid. The pure acid may be subsequently obtained by fractional distillation as an extremely explosive colorless liquid with an unpleasant smell.[2]

- NaN3 + HCl → HN3 + NaCl

Its aqueous solution can also be prepared by treatment of barium azide solution with dilute sulfuric acid, filtering the insoluble barium sulfate.[7]

It was originally prepared by the reaction of aqueous hydrazine with nitrous acid:

- N2H4 + HNO2 → HN3 + 2 H2O

With the hydrazinium cation (N

2H+

5) this reaction is written as:

- N

2H+

5 + HNO2 → HN3 + H2O + H3O+

Other oxidizing agents, such as hydrogen peroxide, nitrosyl chloride, trichloramine or nitric acid, can also be used to produce hydrazoic acid from hydrazine.[8]

Destruction prior to disposal

The hydrazoic acid reacts with nitrous acid:

- HN3 + HNO2 → N2O + N2 + H2O

This reaction is unusual in that it involves compounds with nitrogen in four different oxidation states.[9]

Azides also decompose with sodium nitrite when acidified. This is a method of destroying residual azides, prior to disposal.[10]

- 2 NaN3 + 2 HNO2 → 3 N2 + 2 NO + 2 NaOH

Reactions

In its properties hydrazoic acid shows some analogy to the halogen acids, since it forms poorly soluble (in water) lead, silver and mercury(I) salts. The metallic salts all crystallize in the anhydrous form and decompose on heating, leaving a residue of the pure metal.[2] It is a weak acid (pKa = 4.75.[6]) Its heavy metal salts are explosive and readily interact with the alkyl iodides. Azides of heavier alkali metals (excluding lithium) or alkaline earth metals are not explosive, but decompose in a more controlled way upon heating, releasing spectroscopically-pure N

2 gas.[11] Solutions of hydrazoic acid dissolve many metals (e.g. zinc, iron) with liberation of hydrogen and formation of salts, which are called azides (formerly also called azoimides or hydrazoates).

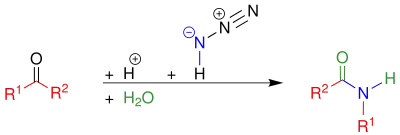

Hydrazoic acid may react with carbonyl derivatives, including aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids, to give an amine or amide, with expulsion of nitrogen. This is called Schmidt reaction or Schmidt rearrangement.

Dissolution in the strongest acids produces explosive salts containing the H

2N=N=N+

ion, for example:[11]

- HN=N=N + HSbCl

6 → [H

2N=N=N]+

[SbCl

6]−

The ion H

2N=N=N+

is isoelectronic to diazomethane.

The decomposition of hydrazoic acid, triggered by shock, friction, spark, etc. goes as follows:

- 2 HN

3 → H

2 + 3 N

2

Hydrazoic acid undergoes unimolecular decomposition at sufficient energy:

- HN

3 → NH + N

2

The lowest energy pathway produces NH in the triplet state, making it a spin-forbidden reaction. This is one of the few reactions whose rate has been determined for specific amounts of vibrational energy in the ground electronic state, by laser photodissociation studies. [12] In addition, these unimolecular rates have been analyzed theoretically, and the experimental and calculated rates are in reasonable agreement. [13]

Toxicity

Hydrazoic acid is volatile and highly toxic. It has a pungent smell and its vapor can cause violent headaches. The compound acts as a non-cumulative poison.

Applications

2-Furonitrile, a pharmaceutical intermediate and potential artificial sweetening agent has been prepared in good yield by treating furfural with a mixture of hydrazoic acid (HN3) and perchloric acid in the presence of magnesium perchlorate in the benzene solution at 35 °C.[14][15]

The all gas-phase iodine laser (AGIL) mixes gaseous hydrazoic acid with chlorine to produce excited nitrogen chloride, which is then used to cause iodine to lase; this avoids the liquid chemistry requirements of COIL lasers.

References

- ↑ Pradyot Patnaik. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill, 2002, ISBN 0-07-049439-8

- 1 2 3 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–83. This also contains a detailed description of the contemporaneous production process.

- ↑ Dictionary of Inorganic and Organometallic Compounds. Chapman & Hall.

- ↑ Curtius, Theodor (1890). "Ueber Stickstoffwasserstoffsäure (Azoimid) N3H" [On hydrazoic acid (azoimide) N3H]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 23 (2): 3023–3033. doi:10.1002/cber.189002302232.

- ↑ Furman, David; Dubnikova, Faina; van Duin, Adri C. T.; Zeiri, Yehuda; Kosloff, Ronnie (2016-03-10). "Reactive Force Field for Liquid Hydrazoic Acid with Applications to Detonation Chemistry". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 120 (9): 4744–4752. Bibcode:2016APS..MARH20013F. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b10812. ISSN 1932-7447.

- 1 2 Catherine E. Housecroft; Alan G. Sharpe (2008). "Chapter 15: The group 15 elements". Inorganic Chemistry, 3rd Edition. Pearson. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ↑ L . F. Audrieth, C. F. Gibbs Hydrogen Azide in Aqueous and Ethereal Solution" Inorganic Syntheses 1939, vol. 1, pp. 71-79.

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ↑ Greenwood, pp. 461–464.

- ↑ Committee on Prudent Practices for Handling, Storage, and Disposal of Chemicals in Laboratories, Board on Chemical Sciences and Technology, Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications, National Research Council (1995). Prudent practices in the laboratory: handling and disposal of chemicals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. ISBN 0-309-05229-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Egon Wiberg; Nils Wiberg; Arnold Frederick Holleman (2001). "The Nitrogen Group". Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press. p. 625. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ↑ Foy, B.R.; Casassa, M.P.; Stephenson, J.C.; King, D.S. (1990). "Overtone-excited HN

3 (X1A') - Anharmonic resonance, homogeneous linewidths, and dissociation rates". Journal of Chemical Physics. 92: 2782–2789. doi:10.1063/1.457924. - ↑ Besora, M.; Harvey, J.N. (2008). "Understanding the rate of spin-forbidden thermolysis of HN

3 and CH

3N

3". Journal of Chemical Physics. 129 (4): 044303. doi:10.1063/1.2953697. PMID 18681642. - ↑ P. A. Pavlov; Kul'nevich, V. G. (1986). "Synthesis of 5-substituted furannitriles and their reaction with hydrazine". Khimiya Geterotsiklicheskikh Soedinenii. 2: 181–186.

- ↑ B. Bandgar; Makone, S. (2006). "Organic reactions in water. Transformation of aldehydes to nitriles using NBS under mild conditions". Synthetic Communications. 36 (10): 1347–1352. doi:10.1080/00397910500522009. S2CID 98593006.

External links

Media related to Hydrogen azide at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hydrogen azide at Wikimedia Commons- OSHA: Hydrazoic Acid