Löfgren syndrome

| Löfgren syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Löfgren syndrome includes some of the same symptoms as traditional sarcoidosis, and presents with erythema nodosum (especially of the lower extremities), bilateral arthritis of the ankle joints, and hilar lymphadenopathy. (Note: Other symptoms are classically not present in Löfgren syndrome.) | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

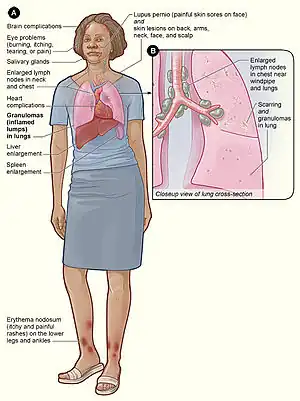

Löfgren syndrome is a type of acute sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disorder characterized the formation of granulomas.[1] Common symptoms include rapid onset of swollen lymph nodes in the chest (hilar lymphadenopathy), tender red nodules on the shins (erythema nodosum), fever, and arthritis.[2] Some have considered the condition to be imprecisely defined.[3]

The exact cause is poorly understood, but is thought to be influenced by genetic and environmental factors.[1] Recent studies have demonstrated a strong association with the HLA-DRB1*03 gene[4].

The treatment of choice for Löfgren syndrome are NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). However, the prognosis of Löfgren syndrome is favorable and most cases resolve on their own.[1]

Löfgren syndrome was first described in 1953 by Sven Halvar Löfgren, a Swedish physician.[5][6] It is more common in women than men, and is more frequent in those of Scandinavian, Irish, African and Puerto Rican heritage.[7]

Signs and symptoms

Löfgren syndrome is characterized by enlargement of the lymph nodes near the inner border of the lungs (called "hilar lymphadenopathy") as seen on x-ray. Tender red nodules (erythema nodosum) are classically present on the shins, predominantly in women. It may also be accompanied by arthritis (more prominent in men) and fever. The arthritis is often acute and involves the lower extremities, particularly the ankles.[2]

Löfgren syndrome consists of the three primary symptoms of erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on chest radiograph, and joint pain.

Cause

The cause of Löfgren syndrome is complex and poorly understood.[1] Both environmental and genetic factors likely contribute to disease onset.[1][4] It is theorized that individuals with genetic susceptibility are exposed to a certain environmental trigger, causing immune activation and disease onset.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the HLA-DRB1*03 is strongly associated with Löfgren syndrome.[4] Moreover, the onset of Löfgren syndrome varies depending on season, with most cases appearing during the springtime.[1][4] Others have identified insecticides, agricultural employment, and microbial bioaerosols as possible environmental triggers.[8]

The exaggerated immune response characteristic of Löfgren syndrome is mediated by macrophages, which stimulate granuloma formation after exposure to an environmental trigger. CD4+ T cells also play a critical role in this process by releasing inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, IL-18, and interferon (IFN)-gamma.

Diagnosis

The triad of erythema nodosum, acute arthritis, and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy is highly specific (>95%) for the diagnosis of Löfgren syndrome. When the triad is present, further testing with additional imaging and laboratory testing is unnecessary.

Treatment

NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are the usual recommended treatment for Löfgren syndrome. Colchicine or low-dose prednisone may also be used.

Epidemiology

Löfgren syndrome is more common in women than men.[1] Age of onset typically occurs between between 30 and 40 years of age, with a second peak between 45 and 60 years of age in females only.[4] It also occurs more frequently in individuals of Scandinavian, Irish, African and Puerto Rican heritage[7].

Prognosis

Löfgren syndrome is associated with a good prognosis, with > 90% of patients experiencing spontaneous disease resolution within 2 years. In contrast, patients with the disfiguring skin condition lupus pernio or cardiac or neurologic involvement rarely experience disease remission.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mitwirkender, Karakaya, Bekir Mitwirkender Kaiser, Ylva Mitwirkender van Moorsel, Coline H. M. Mitwirkender Grunewald, Johan. Löfgren's Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Disease Pathogenesis. OCLC 1187651671. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- 1 2 Sam, Amir H.; James T.H. Teo (2010). Rapid Medicine. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405183239.

- ↑ Grunewald J, Eklund A (January 2007). "Sex-specific manifestations of Löfgren's syndrome". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175 (1): 40–44. doi:10.1164/rccm.200608-1197OC. PMC 1899259. PMID 17023727.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grunewald J, Eklund A (February 2009). "Löfgren's syndrome: human leukocyte antigen strongly influences the disease course". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 179 (4): 307–312. doi:10.1164/rccm.200807-1082OC. PMID 18996998.

- ↑ Löfgren S (1953). "Primary pulmonary sarcoidosis. I. Early signs and symptoms". Acta Med Scand. 145 (6): 424–431. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1953.tb07039.x. PMID 13079656.

- ↑ "Sven Halvar Löfgren biography". Archived from the original on 2018-02-09. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- 1 2 Newman, Lee S.; Rose, Cecile S.; Maier, Lisa A. (1997-04-24). "Sarcoidosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (17): 1224–1234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199704243361706. ISSN 0028-4793. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ↑ Newman, Lee S.; Rose, Cecile S.; Bresnitz, Eddy A.; Rossman, Milton D.; Barnard, Juliana; Frederick, Margaret; Terrin, Michael L.; Weinberger, Steven E.; Moller, David R.; McLennan, Geoffrey; Hunninghake, Gary (2004-12-15). "A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis: Environmental and Occupational Risk Factors". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 170 (12): 1324–1330. doi:10.1164/rccm.200402-249OC. ISSN 1073-449X. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

External links

| Classification |

|---|