LRBA deficiency

| LRBA deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

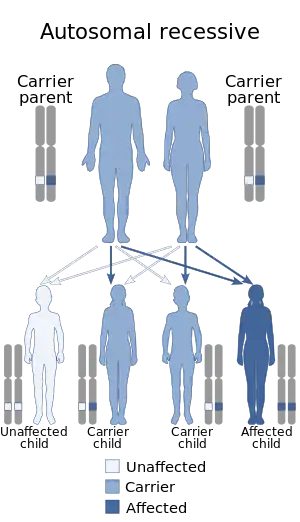

| Two unaffected parents each carry one copy of a gene mutation for an autosomal recessive disorder. They have one affected child and three unaffected children, two of which carry one copy of the gene mutation. | |

LRBA deficiency is a rare genetic disorder of the immune system. This disorder is caused by a mutation in the gene LRBA. LRBA stands for “lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-responsive and beige-like anchor protein”. This condition is characterized by autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, and immune deficiency. It was first described by Gabriela Lopez-Herrera from University College London in 2012.[1] Investigators in the laboratory of Dr. Michael Lenardo Archived 2015-09-09 at the Wayback Machine at National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health and Dr. Michael Jordan Archived 2020-05-19 at the Wayback Machine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center later described this condition and therapy in 2015.[2]

Signs and symptoms

LRBA deficiency presents as a syndrome of autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, and humoral immune deficiency. Predominant clinical problems include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), and an autoimmune enteropathy.[1] Before the discovery of these gene mutations, patients were diagnosed with common variable immune deficiency (CVID), which is characterized by low antibody levels and recurrent infections. Infections mostly affect the respiratory tract, as many patients suffer from chronic lung disease, pneumonias, and bronchiectasis. Lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (ILD) is also observed, which complicates breathing and leads to impairment of lung function and mortality.[2] Infections can also occur at other sites, such as the eyes, skin and gastrointestinal tract. Many patients suffer from chronic diarrhea and inflammatory bowel disease. Other clinical features can include hepatosplenomegaly, reoccurring warts, growth retardation, allergic dermatitis, and arthritis.[1] Notably, LRBA deficiency has also been associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus.[2] There is significant clinical phenotypic overlap with disease caused by CTLA4 haploinsufficiency. Since LRBA loss results in a loss of CTLA4 protein, the immune dysregulation syndrome of LRBA deficient patients can be attributed to the secondary loss of CTLA4. Because the predominant features of the disease include autoantibody-mediated disease (AIHA, ITP), Treg defects (resembling those found in CTLA4 haploinsufficient patients), autoimmune infiltration (of non-lymphoid organs, also resembling that found in CTLA4 haploinsufficient patients), and enteropathy, the disease has been termed LATAIE for LRBA deficiency with autoantibodies, Treg defects, autoimmune infiltration, and enteropathy.

Genetics

LRBA deficiency is caused by biallelic loss-of-function mutations in the gene LRBA. LRBA maps to human chromosome 4q31.3, has 58 exons, and encodes for one of the largest intracellular proteins, LRBA.[2][3][4] The LRBA protein belongs to a distinct sub-family of proteins characterized by a “beige and CHS”, or BEACH, domain followed by repeated WD40 domains at the carboxy terminus.[5] These related BEACH-containing proteins have been found to regulate trafficking of intracellular vesicles. These loss-of-function LRBA mutations decrease or eradicate LRBA protein in patients with this disorder.[2]

Although the function of LRBA is not fully understood, it was recently reported that this protein plays a major immuno-regulatory role in the expression, function, and trafficking of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4). CTLA4 is an immune effector molecule that acts as an inhibitory checkpoint for the immune response. CTLA4 resides in intracellular vesicles, or endosomes, of regulatory T cells (Tregs) that are released and mobilize to the cell surface after T cell receptor stimulation.[2]

It is hypothesized that LRBA deficiency sufficiently impairs post-translational CTLA4 expression, as the abundance of CTLA4 protein in patients is significantly lower than normal. Knockdown of LRBA in wildtype cells, also leads to a post-translational loss of CTLA4 protein. Co-immunopreciptation studies suggest that LRBA binds to the cytoplasmic tail of CTLA4. By binding to the tail, LRBA may protect and regulate the degradation of CTLA4 by blocking its trafficking to lysosomes for degradation.[2]

Inheritance

LRBA deficiency is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. In autosomal recessive inheritance, two copies of an abnormal gene must be present in order for the disease to develop. Typically, this means both parents of an affected child silently carry one abnormal gene. This also explains why reported cases of LRBA deficiency have often involved homozygosity via consanguinity or geographically isolated communities.

Parents of a child with LRBA deficiency have a 25% chance of having another affected child with each pregnancy. This risk is independent of prior children’s status. For example, if the first two children in a family are affected, the next child has the same 25% risk of inheriting the mutation. All affected individuals have two abnormal copies of LRBA. Children who inherit only one abnormal copy of LRBA will not develop LRBA deficiency although they may have affected children, particularly if they marry within the family.

Diagnosis

Individuals show markedly low immunoglobulin levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM.

Treatment

A new investigation has identified a seemingly successful treatment for LRBA deficiency by targeting CTLA4. Abatacept, an approved drug for rheumatoid arthritis, mimics the function of CTLA4 and has found to reverse life-threatening symptoms.[2]

The study included nine patients that exhibited improved clinical status and halted inflammatory conditions with minimal infectious or autoimmune complications. The study also suggests that therapies like chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, which inhibit lysosomal degradation, may prove to be effective, as well.[2]

Larger cohorts are required to further validate these therapeutic approaches as effective long-term treatments for this disorder.

References

- 1 2 3 Lopez-Herrera, Gabriela; Tampella, Giacomo; Pan-Hammarström, Qiang; Herholz, Peer; Trujillo-Vargas, Claudia M.; Phadwal, Kanchan; Simon, Anna Katharina; Moutschen, Michel; Etzioni, Amos; Mory, Adi; Srugo, Izhak; Melamed, Doron; Hultenby, Kjell; Liu, Chonghai; Baronio, Manuela; Vitali, Massimiliano; Philippet, Pierre; Dideberg, Vinciane; Aghamohammadi, Asghar; Rezaei, Nima; Enright, Victoria; Du, Likun; Salzer, Ulrich; Eibel, Hermann; Pfeifer, Dietmar; Veelken, Hendrik; Stauss, Hans; Lougaris, Vassilios; Plebani, Alessandro; Gertz, E. Michael; Schäffer, Alejandro A.; Hammarström, Lennart; Grimbacher, Bodo (June 2012). "Deleterious Mutations in LRBA Are Associated with a Syndrome of Immune Deficiency and Autoimmunity". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 90 (6): 986–1001. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.015. PMC 3370280. PMID 22608502.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lo, B.; Zhang, K.; Lu, W.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Kanellopoulou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Fritz, J. M.; Marsh, R.; Husami, A.; Kissell, D.; Nortman, S.; Chaturvedi, V.; Haines, H.; Young, L. R.; Mo, J.; Filipovich, A. H.; Bleesing, J. J.; Mustillo, P.; Stephens, M.; Rueda, C. M.; Chougnet, C. A.; Hoebe, K.; McElwee, J.; Hughes, J. D.; Karakoc-Aydiner, E.; Matthews, H. F.; Price, S.; Su, H. C.; Rao, V. K.; Lenardo, M. J.; Jordan, M. B. (23 July 2015). "Patients with LRBA deficiency show CTLA4 loss and immune dysregulation responsive to abatacept therapy". Science. 349 (6246): 436–440. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..436L. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1663. PMID 26206937.

- ↑ "OMIM# 606453". Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ↑ "Genecards - LRBA gene". Archived from the original on 2020-10-17. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ↑ de Souza, N; Vallier, LG; Fares, H; Greenwald, I (February 2007). "SEL-2, the C. elegans neurobeachin/LRBA homolog, is a negative regulator of lin-12/Notch activity and affects endosomal traffic in polarized epithelial cells". Development. 134 (4): 691–702. doi:10.1242/dev.02767. PMID 17215302.