Lomentospora prolificans

| Lomentospora prolificans | |

|---|---|

| |

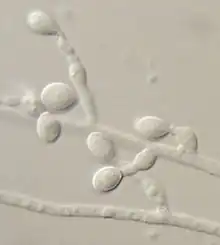

| Photomicrograph of colony growing on Modified Leonian's agar | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Sordariomycetes |

| Order: | Microascales |

| Family: | Microascaceae |

| Genus: | Lomentospora |

| Species: | L. prolificans |

| Binomial name | |

| Lomentospora prolificans Hennebert & B.G.Desai(1974) | |

| Type strain | |

| CBS 467.74; UAMH 7149 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Lomentospora prolificans is an emerging opportunistic fungal pathogen that causes a wide variety of infections in immunologically normal and immunosuppressed people and animals.[1][2][3] It is resistant to most antifungal drugs and infections are often fatal.[3] Drugs targeting the Class II dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) proteins of L. prolificans, Scedosporium, Aspergillus and other rare moulds are the basis for at least one new therapy, Olorofim, which is currently in phase 2b clinical trials and has received breakthrough status by FDA.[4] For information on all DHODH proteins, please see Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase.

Morphology

Lomentospora prolificans produces small, delicate annellides with a distinct basal swelling peculiar to this species and absent in the closely related species, Scedosporium apiospermum. Annellides necks become long and distinctly annellated with age. Annellides occur individually or in clusters irregularly along undifferentiated hyphae, frequently exhibiting a pronounced penicillate arrangement in older cultures. Conidia are smooth-walled, light to dark brown, 3–7 x 2–3 μm, accumulating in slime droplets at annelide apices. Colonies of Lomentospora prolificans are grey to brownish, spreading, with scant, cobweb-like aerial mycelium recalling a moth-eaten woolen garment. This species is sensitive to cycloheximide. As this species may be slow to emerge from clinical materials, specimens in which this agent is suspected often require an extended period of culture incubation (e.g., up to 4 weeks).[5]

Ecology

Lomentospora prolificans is a soil fungus, and has been found in the soils of ornamental plants[lower-alpha 1] and greenhouse plants.[lower-alpha 2] Along with other fungi, Lomentospora prolificans has been isolated from soils of Ficus benjamina and Heptapleurum actinophyllum plantings in hospitals, suggesting that these materials have potential to serve as reservoirs of nosocomial fungal pathogens.[7]

Drug resistance

Infections caused by Lomentospora prolificans are recognized to be difficult to treat due to the tendency of this species to exhibit resistance to many commonly used antifungal agents.[5][8][9][10] Successful control of disseminated Lomentospora prolificans infection can be obtained with a combination of voriconazole and terbinafine,[11] but some strains are resistant to this treatment. Drugs that might also be of help are posaconazole, miltefosine and albaconazole. Albaconazole is in phase III clinical trials.

History

The genus Lomentospora was erected by G. Hennebert and B.G. Desai in 1974 to accommodate a culture obtained from greenhouse soil originating from a forest in Belgium.[12] The fungus, which they named Lomentospora prolificans, was thought incorrectly to be related to the genus Beauveria - a group of insect-pathogenic soil fungi affiliated with the order Hypocreales.[12][13] The genus name "Lomentospora" referred to the shape of the apex of the spore-bearing cell, which the authors interpreted to be a rachis resembling a bean pod of the sort constricted at each seed. The species epithet "prolificans" derived from the prolific nature of the mold's sporulation. The fungus was later independently described as Scedosporium inflatum by Malloch and Salkin in 1984 from a bone biopsy of the foot of a boy who had stepped on a nail.[lower-alpha 3][14] The species epithet "inflatum" referred to the characteristically swollen base of the spore-bearing cell which they recognized correctly to be an annelide. Malloch and Salkin did not observe a sexual state, however they recognized the fungus to be associated with the family Microascaceae, and suspected it to be allied with the genus Pseudallescheria.[14] In 1991, Guého and De Hoog re-examined a set of cultures of Scedosporium-like fungi from clinical cases by careful morphological examination and the evaluation of DNA-DNA reassociation complementarity. Along with two strains from their own work, they found the cultures of Hennebert & Desai and Malloch & Salkin to constitute a single species which they confirmed to belong in the genus Scedosporium.[15] Lomentospora prolificans was then transferred to Scedosporium as S. prolificans, and Scedosporium inflatum became a synonym. This synonymy has since been confirmed by phylogenetic analysis of the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer regions.[16] Despite this change, and even as recently as 2012, the name Scedosporium inflatum has continued to appear in the medical literature.[17][18]

In 2014 Lackner et al. proposed a move back to L. prolificans.[19]

Human disease

Lomentospora prolificans has been recognized as an agent of opportunistic human disease since the 1990s. This species is primarily associated with subcutaneous lesions arising from injury following traumatic implantation of the agent via contaminated splinters or plant thorns. The majority of Lomentospora prolificans infections in immunologically normal people remain localized, characteristically with bone or joint involvement.[8]

Disseminated infections from Lomentospora prolificans are largely limited to people with pre-existing immune impairment. Notably, Lomentospora prolificans exhibits varying tolerance to all currently available antifungal agents. This is particularly true of strains recovered from disseminated infections, and these infections carry a high mortality. Lomentospora prolificans has also been known to cause disseminated disease secondary to myeloblastic leukemia[9] and following lung transplant.[20] In otherwise healthy people, it was recorded as a cause of corneal infection following a lawn trimmer mishap,[lower-alpha 4] and bone infection following trauma.[14]

Notes

References

- ↑ Cortez KJ, Roilides E, Quiroz-Telles F, et al. (2008). "Infections caused by Scedosporium spp". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (1): 157–97. doi:10.1128/CMR.00039-07. PMC 2223844. PMID 18202441.

- ↑ Elad, Daniel (1 January 2011). "Infections caused by fungi of the Scedosporium/Pseudallescheria complex in veterinary species". The Veterinary Journal. 187 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.05.028. PMID 20580291.

- 1 2 Rodriguez-Tudela, Juan Luis; Rodriguez-Tudela, Juan Luis; Berenguer, Juan; Guarro, Josep; Kantarcioglu, A. Serda; Horre, Regine; Sybren De Hoog, G.; Cuenca-Estrella, Manuel (1 January 2009). "Epidemiology and outcome of Scedosporium prolificans infection, a review of 162 cases". Medical Mycology. 47 (4): 359–370. doi:10.1080/13693780802524506. PMID 19031336.

- ↑ "Evaluate F901318 Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections in Patients Lacking Treatment Options - Tabular View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- 1 2 Sigler, L (2003). "Chapter 11: Miscellaneous opportunistic fungi: Microascaceae and other Ascomycetes, Hyphomycetes, Coelomycetes and Basidiomycetes". In Howard DH (ed.). Pathogenic fungi in humans and animals (2nd ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 637–676. ISBN 978-0824706838.

- 1 2 3 4 Sigler, L. "UAMH Culture Collection Catalogue". UAMH Centre for Global Microfungal Biodiversity. University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ↑ Summerbell, RC; Krajden S; Kane J (1989). "Potted plants in hospitals as reservoirs of pathogenic fungi". Mycopathologia. 106 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1007/bf00436921. PMID 2671744.

- 1 2 Matlani, M; Kaur, R; Shweta (January 2013). "A case of Scedosporium prolificans osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent child, misdiagnosed as tubercular osteomyelitis". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 58 (1): 80–1. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.105319. PMC 3555384. PMID 23372223.

- 1 2 Roberto, Reinoso; et al. (2013). "Fatal disseminated Scedosporium prolificans infection initiated by ophthalmic involvement in a patient with acute myeloblastic leukemia". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 76 (3): 375–378. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.03.006. PMID 23602787.

- ↑ Salkin, I. F.; McGinnis, M. R.; Dykstra, M. J.; Rinaldi, M. G. (1988). "Scedosporium inflatum, an emerging pathogen". J Clin Microbiol. 26 (3): 498–503. doi:10.1128/JCM.26.3.498-503.1988. PMC 266320. PMID 3356789.

- ↑ Howden, BP; Slavin, MA; Schwarer, AP; Mijch, AM (February 2003). "Successful control of disseminated Scedosporium prolificans infection with a combination of voriconazole and terbinafine". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 22 (2): 111–113. doi:10.1007/s10096-002-0877-z. PMID 12627286.

- 1 2 Hennebert, G. L.; Desai, B.G. (1974). "Lomentospora prolificans, a new hyphomycete from greenhouse soil". Mycotaxon. 1 (1): 45–50. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ↑ MycoBank. "Beauveria". Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 Malloch, D; Salkin IF (1984). "A new species of Scedosporium associated with osteomyelitis in humans". Mycotaxon. 21: 247–255. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ↑ Guého E; de Hoog GS (1991). "Taxonomy of the medical species of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium". Journal de Mycologie Médicale. 1: 3–9.

- ↑ Lennon, PA; Cooper CR; Salkin IF; Lee SB (1994). "Ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer analysis supports synonymy of Scedosporium inflatum and Lomentospora prolificans". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 32 (10): 2413–2416. doi:10.1128/JCM.32.10.2413-2416.1994.

- ↑ Cetrulo, Curtis L.; Barone, Angelo A. Leto; Jordan, Kathleen; Chang, David S.; Louie, Kevin; Buntic, Rudolf F.; Brooks, Darrell (1 February 2012). "A multi-disciplinary approach to the management of fungal osteomyelitis: Current concepts in post-traumatic lower extremity reconstruction: A case report". Microsurgery. 32 (2): 144–147. doi:10.1002/micr.20956. PMID 22389900.

- ↑ Taylor, Alexandra; Wiffen, Steven J; Kennedy, Christopher J (1 February 2002). "Post-traumatic Scedosporium inflatum endophthalmitis". Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 30 (1): 47–48. doi:10.1046/j.1442-9071.2002.00475.x. PMID 11885796.

- ↑ Lackner, Michaela; de Hoog, G. Sybren; Yang, Liyue; Ferreira Moreno, Leandro; Ahmed, Sarah A.; Andreas, Fritz; Kaltseis, Josef; Nagl, Markus; Lass-Flörl, Cornelia; Risslegger, Brigitte; Rambach, Günter (1 July 2014). "Proposed nomenclature for Pseudallescheria, Scedosporium and related genera". Fungal Diversity. 67 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s13225-014-0295-4. ISSN 1878-9129.

- ↑ Sayah, D.M.; Schwartz, B.S.; Kukreja, J.; Singer, J.P.; Golden, J.A.; Leard, L.E. (1 April 2013). "Scedosporium prolificans pericarditis and mycotic aortic aneurysm in a lung transplant recipient receiving voriconazole prophylaxis". Transplant Infectious Disease. 15 (2): E70–E74. doi:10.1111/tid.12056. PMID 23387799.

External links

- Photos of Scedosporium prolificans on MycoBank Archived 2 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine