Medical education

Medical education is education related to the practice of being a medical practitioner, including the initial training to become a physician (i.e., medical school and internship) and additional training thereafter (e.g., residency, fellowship, and continuing medical education).

Medical education and training varies considerably across the world. Various teaching methodologies have been used in medical education, which is an active area of educational research.[1]

Medical education is also the subject-didactic academic field of educating medical doctors at all levels, including entry-level, post-graduate, and continuing medical education. Specific requirements such as entrustable professional activities must be met before moving on in stages of medical education.

Common techniques and evidence base

Medical education applies theories of pedagogy specifically in the context of medical education. Medical education has been a leader in the field of evidence-based education, through the development of evidence syntheses such as the Best Evidence Medical Education collection, formed in 1999, which aimed to "move from opinion-based education to evidence-based education".[2] Common evidence-based techniques include the Objective structured clinical examination (commonly known as the 'OSCE) [3] to assess clinical skills, and reliable checklist-based assessments to determine the development of soft skills such as professionalism.[4] However there is a persistence of ineffective instructional methods in medical education, such as the matching of teaching to Learning styles[5] and Edgar Dales 'Cone of Learning'[6]

Entry-level education

Entry-level medical education programs are tertiary-level courses undertaken at a medical school. Depending on jurisdiction and university, these may be either undergraduate-entry (most of Europe, Asia, South America and Oceania), or graduate-entry programs (mainly Australia, Philippines and North America). Some jurisdictions and universities provide both undergraduate entry programs and graduate entry programs (Australia, South Korea).

In general, initial training is taken at medical school. Traditionally initial medical education is divided between preclinical and clinical studies. The former consists of the basic sciences such as anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, pathology. The latter consists of teaching in the various areas of clinical medicine such as internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, general practice and surgery.

There has been a proliferation of programmes that combine medical training with research (M.D./Ph.D.) or management programmes (M.D./ MBA), although this has been criticised because extended interruption to clinical study has been shown to have a detrimental effect on ultimate clinical knowledge.[7]

The LCME and the "Function and Structure of a Medical School"

The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) is a committee of educational accreditation for schools of medicine leading to an MD in the United States and Canada. In order to maintain accreditation, medical schools are required to ensure that students meet a certain set of standards and competencies, defined by the accreditation committees. The "Function and Structure of a Medical School" article is a yearly published article from the LCME that defines 12 accreditation standards.[8]

Entrustable Professional Activities for entering residency

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has recommended thirteen Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) that medical students should be expected to accomplish prior to beginning a residency program.[9][10][11] EPAs are based on the integrated core competencies developed over the course of medical school training. Each EPA lists its key feature, associated competencies, and observed behaviors required for completion of that activity. The students progress through levels of understanding and capability, developing with decreasing need for direct supervision.[9][10][11] Eventually students should be able to perform each activity independently, only requiring assistance in situations of unique or uncommon complexity.[9][10][11]

The list of topics that EPAs address include:

- History and physical exam skills

- Differential diagnosis

- Diagnostic/screening tests

- Orders and prescriptions

- Patient encounter documentation

- Oral presentations of patient encounters

- Clinical questioning/using evidence

- Patient handovers/transitions of care

- Teamwork

- Urgent/Emergency care

- Informed consent

- Procedures

- Safety and improvement

Postgraduate education

Following completion of entry-level training, newly graduated doctors are often required to undertake a period of supervised practice before full registration is granted; this is most often of one-year duration and may be referred to as an "internship" or "provisional registration" or "residency".

Further training in a particular field of medicine may be undertaken. In the U.S., further specialized training, completed after residency is referred to as "fellowship". In some jurisdictions, this is commenced immediately following completion of entry-level training, while other jurisdictions require junior doctors to undertake generalist (unstreamed) training for a number of years before commencing specialization.

Each residency and fellowship program is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), a non-profit organization led by physicians with the goal of enhancing educational standards among physicians. The ACGME oversees all MD and DO residency programs in the United States. As of 2019, there were approximately 11,700 ACGME accredited residencies and fellowship programs in 181 specialties and subspecialties.[12]

Education theory itself is becoming an integral part of postgraduate medical training. Formal qualifications in education are also becoming the norm for medical educators, such that there has been a rapid increase in the number of available graduate programs in medical education.[13][14]

Continuing medical education

In most countries, continuing medical education (CME) courses are required for continued licensing.[15] CME requirements vary by state and by country. In the USA, accreditation is overseen by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). Physicians often attend dedicated lectures, grand rounds, conferences, and performance improvement activities in order to fulfill their requirements. Additionally, physicians are increasingly opting to pursue further graduate-level training in the formal study of medical education as a pathway for continuing professional development.[16][17]

Online learning

Medical education is increasingly utilizing online teaching, usually within learning management systems (LMSs) or virtual learning environments (VLEs).[18][19] Additionally, several medical schools have incorporated the use of blended learning combining the use of video, asynchronous, and in-person exercises.[20][21] A landmark scoping review published in 2018 demonstrated that online teaching modalities are becoming increasingly prevalent in medical education, with associated high student satisfaction and improvement on knowledge tests. However, the use of evidence-based multimedia design principles in the development of online lectures was seldom reported, despite their known effectiveness in medical student contexts.[22] To enhance variety in an online delivery environment, the use of serious games, which have previously shown benefit in medical education,[23] can be incorporated to break the monotony of online-delivered lectures.[24]

Research areas into online medical education include practical applications, including simulated patients and virtual medical records (see also: telehealth).[25] When compared to no intervention, simulation in medical education training is associated with positive effects on knowledge, skills, and behaviors and moderate effects for patient outcomes.[26] However, data is inconsistent on the effectiveness of asynchronous online learning when compared to traditional in-person lectures.[27][28] Furthermore, studies utilizing modern visualization technology (i.e. virtual and augmented reality) have shown great promise as means to supplement lesson content in physiological and anatomical education.[29][30]

Telemedicine/telehealth education

With the advent of telemedicine (aka telehealth), students learn to interact with and treat patients online, an increasingly important skill in medical education.[31][32][33][34] In training, students and clinicians enter a "virtual patient room" in which they interact and share information with a simulated or real patient actors. Students are assessed based on professionalism, communication, medical history gathering, physical exam, and ability to make shared decisions with the patient actor.[35][36]

Medical education systems by country

At present, in the United Kingdom, a typical medicine course at university is 5 years or 4 years if the student already holds a degree. Among some institutions and for some students, it may be 6 years (including the selection of an intercalated BSc—taking one year—at some point after the pre-clinical studies). All programs culminate in the Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery degree (abbreviated MBChB, MBBS, MBBCh, BM, etc.). This is followed by 2 clinical foundation years afterward, namely F1 and F2, similar to internship training. Students register with the UK General Medical Council at the end of F1. At the end of F2, they may pursue further years of study. The system in Australia is very similar, with registration by the Australian Medical Council (AMC).

In the US and Canada, a potential medical student must first complete an undergraduate degree in any subject before applying to a graduate medical school to pursue an (M.D. or D.O.) program. U.S. medical schools are almost all four-year programs. Some students opt for the research-focused M.D./Ph.D. dual degree program, which is usually completed in 7–10 years. There are certain courses that are pre-requisite for being accepted to medical school, such as general chemistry, organic chemistry, physics, mathematics, biology, English, labwork, etc. The specific requirements vary by school.

In Australia, there are two pathways to a medical degree. Students can choose to take a five- or six-year undergraduate medical degree Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS or BMed) as a first tertiary degree directly after secondary school graduation, or first complete a bachelor's degree (in general three years, usually in the medical sciences) and then apply for a four-year graduate entry Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) program.[37][38]

See:

|

|

Norms and values

Along with training individuals in the practice of medicine, medical education will influence the norms and values of those people who pass through it. This occur through explicit training in medical ethics, or implicitly through "hidden curriculum" a body of norms and values that students will come to understand implicitly but is not formally taught.[lower-alpha 1] The hidden curriculum and formal ethics curriculum will often contradict one another.

The aims of medical ethics training are to give medical doctors the ability to recognise ethical issues, reason about them morally and legally when making clinical decisions, and be able to interact to obtain the information necessary to do so.[lower-alpha 2]

The hidden curriculum may include the use of unprofessional behaviours for efficiency[lower-alpha 3] or viewing the academic hierarchy as more important than the patient.[lower-alpha 4] The concept of "professionalism" may be used as a device to ensure obedience, with complaints about ethics and safety being labelled as unprofessional.

Integration with health policy

As medical professional stakeholders in the field of health care (i.e. entities integrally involved in the health care system and affected by reform), the practice of medicine (i.e. diagnosing, treating, and monitoring disease) is directly affected by the ongoing changes in both national and local health policy and economics.[41]

There is a growing call for health professional training programs to not only adopt more rigorous health policy education and leadership training,[42][43][44] but to apply a broader lens to the concept of teaching and implementing health policy through health equity and social disparities that largely affect health and patient outcomes.[45][46] Increased mortality and morbidity rates occur from birth to age 75, attributed to medical care (insurance access, quality of care), individual behavior (smoking, diet, exercise, drugs, risky behavior), socioeconomic and demographic factors (poverty, inequality, racial disparities, segregation), and physical environment (housing, education, transportation, urban planning).[46] A country’s health care delivery system reflects its “underlying values, tolerances, expectations, and cultures of the societies they serve”,[47] and medical professionals stand in a unique position to influence opinion and policy of patients, healthcare administrators, & lawmakers.[42][48]

In order to truly integrate health policy matters into physician and medical education, training should begin as early as possible – ideally during medical school or premedical coursework – to build “foundational knowledge and analytical skills” continued during residency and reinforced throughout clinical practice, like any other core skill or competency.[44] This source further recommends adopting a national standardized core health policy curriculum for medical schools and residencies in order to introduce a core foundation in this much needed area, focusing on four main domains of health care: (1) systems and principles (e.g. financing; payment; models of management; information technology; physician workforce), (2) quality and safety (e.g. quality improvement indicators, measures, and outcomes; patient safety), (3) value and equity (e.g. medical economics, medical decision making, comparative effectiveness, health disparities), and (4) politics and law (e.g. history and consequences of major legislations; adverse events, medical errors, and malpractice).

However limitations to implementing these health policy courses mainly include perceived time constraints from scheduling conflicts, the need for an interdisciplinary faculty team, and lack of research / funding to determine what curriculum design may best suit the program goals.[44][45] Resistance in one pilot program was seen from program directors who did not see the relevance of the elective course and who were bounded by program training requirements limited by scheduling conflicts and inadequate time for non-clinical activities.[49] But for students in one medical school study,[50] those taught higher-intensity curriculum (vs lower-intensity) were “three to four times as likely to perceive themselves as appropriately trained in components of health care systems”, and felt it did not take away from getting poorer training in other areas. Additionally, recruiting and retaining a diverse set of multidisciplinary instructors and policy or economic experts with sufficient knowledge and training may be limited at community-based programs or schools without health policy or public health departments or graduate programs. Remedies may include having online courses, off-site trips to the capitol or health foundations, or dedicated externships, but these have interactive, cost, and time constraints as well. Despite these limitations, several programs in both medical school and residency training have been pioneered.[45][49][51][52][53]

Lastly, more national support and research will be needed to not only establish these programs but to evaluate how to both standardize and innovate the curriculum in a way that is flexible with the changing health care and policy landscape. In the United States, this will involve coordination with the ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education), a private NPO that sets educational and training standards[54] for U.S. residencies and fellowships that determines funding and ability to operate.

Medical education as a subject-didactic field

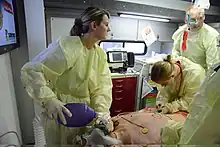

Medical education is also the subject-didactic field of educating medical doctors at all levels, applying theories of pedagogy in the medical context, with its own journals, such as Medical Education. Researchers and practitioners in this field are usually medical doctors or educationalists. Medical curricula vary between medical schools, and are constantly evolving in response to the need of medical students, as well as the resources available.[55] Medical schools have been documented to utilize various forms of problem-based learning, team-based learning, and simulation.[56][57][58][59] The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) publishes standard guidelines regarding goals of medical education, including curriculum design, implementation, and evaluation.[8]

The objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) are widely utilized as a way to assess health science students' clinical abilities in a controlled setting.[60][61] Although used in medical education programs throughout the world, the methodology for assessment may vary between programs and thus attempts to standardize the assessment have been made.[62][63]

Cadaver laboratory

Medical schools and surgical residency programs may utilize cadavers to identify anatomy, study pathology, perform procedures, correlate radiology findings, and identify causes of death.[64][65][66][67][68] With the integration of technology, traditional cadaver dissection has been debated regarding it's effectiveness in medical education, but remains a large component of medical curriculum around the world.[64][68] Didactic courses in cadaver dissection are commonly offered by certified anatomists, scientists, and physicians with a background in the subject.[64]

Medical curriculum and evidence-based medical education journals

Medical curriculum vary widely among medical schools and residency programs, but generally follow an evidence based medical education (EBME) approach.[69] These evidence based approaches are published in medical journals. The list of peer-reviewed medical education journals includes, but is not limited to:

- Academic Medicine

- Medical Education

- Advances in Health Science Education

- Medical Teacher

Open access medical education journals:

- BMC Medical Education

- MedEDPORTAL[70]

- Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Graduate Medical Education and Continuing Medical Education focused journals:

- Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions

- Journal of Graduate Medical Education

This is not a complete list of medical education journals. Each medical journal in this list has a varying impact factor, or mean number of citations indicating how often it is used in scientific research and study.

See also

- Doctors to Be (an occasional series on BBC television)

- INMED

- List of medical schools

- List of medical education agencies

- Objective Structured Clinical Examination

- Progress testing

- Validation of foreign studies and degrees

- Virtual patient

- Perspectives on Medical Education, a journal

Notes

- ↑ See the section "What are the aims of medical ethics" in [40] this lists the five aims of "1 To teach doctors to recognize the humanistic and ethical aspects of medical careers. 2 To enable doctors to examine and affirm their own personal and professional moral commitments. 3 To equip doctors with a foundation of philosophical, social and legal knowledge. 4 To enable doctors to employ this knowledge inclinical reasoning. 5 To equip doctors with the interactional skills needed to apply this insight, knowledge and reasoning to human clinical care"

- ↑ "As in any crisis, the environment has evolved to accept substandard professional behavior in exchange for efficiency or productivity" [39]

- ↑ "In Coulehan’s view, the hidden curriculum places the academic hierarchy—not the patient—at the center of medical education."[39]

References

- ↑ Flores-Mateo G, Argimon JM (July 2007). "Evidence based practice in postgraduate healthcare education: a systematic review". BMC Health Services Research. 7: 119. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-119. PMC 1995214. PMID 17655743.

- ↑ Harden RM, Grant J, Buckley G, Hart IR (1999-01-01). "BEME Guide No. 1: Best Evidence Medical Education". Medical Teacher. 21 (6): 553–62. doi:10.1080/01421599978960. PMID 21281174.

- ↑ Daniels VJ, Pugh D (December 2018). "Twelve tips for developing an OSCE that measures what you want". Medical Teacher. 40 (12): 1208–1213. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1390214. PMID 29069965.

- ↑ Wilkinson TJ, Wade WB, Knock LD (May 2009). "A blueprint to assess professionalism: results of a systematic review". Academic Medicine. 84 (5): 551–8. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819fbaa2. PMID 19704185.

- ↑ Newton PM, Najabat-Lattif HF, Santiago G, Salvi A (2021). "The Learning Styles Neuromyth Is Still Thriving in Medical Education". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 15: 708540. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2021.708540. PMC 8385406. PMID 34456698.

- ↑ Masters K (January 2020). "Edgar Dale's Pyramid of Learning in medical education: Further expansion of the myth". Medical Education. 54 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1111/medu.13813. PMID 31576610.

- ↑ Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Natt N, Rohren CH (August 2007). "Prolonged delays for research training in medical school are associated with poorer subsequent clinical knowledge". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 22 (8): 1101–6. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0200-x. PMC 2305740. PMID 17492473.

- 1 2 "Standards, Publications, & Notification Forms". LCME.org. March 31, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Obeso V (2017). "Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency" (PDF). Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 Ten Cate O (March 2013). "Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities". Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 5 (1): 157–8. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1. PMC 3613304. PMID 24404246.

- 1 2 3 Cate OT (March 2018). "A primer on entrustable professional activities". Korean Journal of Medical Education. 30 (1): 1–10. doi:10.3946/kjme.2018.76. PMC 5840559. PMID 29510603.

- ↑ "Data Resource Book". Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 19: 13–19. 2019.

- ↑ Tekian A, Artino AR (September 2013). "AM last page: master's degree in health professions education programs". Academic Medicine. 88 (9): 1399. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829decf6. PMID 23982511.

- ↑ Tekian A, Artino AR (September 2014). "AM last page. Overview of doctoral programs in health professions education". Academic Medicine. 89 (9): 1309. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000421. PMID 25006714.

- ↑ Ahmed K, Ashrafian H, Hanna GB, Darzi A, Athanasiou T (October 2009). "Assessment of specialists in cardiovascular practice". Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 6 (10): 659–67. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2009.155. PMID 19724254. S2CID 21452983.

- ↑ Cervero RM, Artino AR, Daley BJ, Durning SJ (2017). "Health Professions Education Graduate Programs Are a Pathway to Strengthening Continuing Professional Development". The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 37 (2): 147–151. doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000155. PMID 28562504. S2CID 13954832.

- ↑ Artino AR, Cervero RM, DeZee KJ, Holmboe E, Durning SJ (April 2018). "Graduate Programs in Health Professions Education: Preparing Academic Leaders for Future Challenges". Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 10 (2): 119–122. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00082.1. PMC 5901787. PMID 29686748.

- ↑ Ellaway R, Masters K (June 2008). "AMEE Guide 32: e-Learning in medical education Part 1: Learning, teaching and assessment". Medical Teacher. 30 (5): 455–73. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.475.1660. doi:10.1080/01421590802108331. PMID 18576185. S2CID 13793264.

- ↑ Masters K, Ellaway R (June 2008). "e-Learning in medical education Guide 32 Part 2: Technology, management and design". Medical Teacher. 30 (5): 474–89. doi:10.1080/01421590802108349. PMID 18576186. S2CID 43473920.

- ↑ Evans KH, Thompson AC, O'Brien C, Bryant M, Basaviah P, Prober C, Popat RA (May 2016). "An Innovative Blended Preclinical Curriculum in Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics: Impact on Student Satisfaction and Performance". Academic Medicine. 91 (5): 696–700. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001085. PMID 26796089.

- ↑ Villatoro T, Lackritz K, Chan JS (2019-01-01). "Case-Based Asynchronous Interactive Modules in Undergraduate Medical Education". Academic Pathology. 6: 2374289519884715. doi:10.1177/2374289519884715. PMC 6823976. PMID 31700991.

- ↑ Tang B, Coret A, Qureshi A, Barron H, Ayala AP, Law M (April 2018). "Online Lectures in Undergraduate Medical Education: Scoping Review". JMIR Medical Education. 4 (1): e11. doi:10.2196/mededu.9091. PMC 5915670. PMID 29636322.

- ↑ Birt J, Stromberga Z, Cowling M, Moro C (2018-01-31). "Mobile Mixed Reality for Experiential Learning and Simulation in Medical and Health Sciences Education". Information. 9 (2): 31. doi:10.3390/info9020031. ISSN 2078-2489.

- ↑ Moro C, Stromberga Z (December 2020). "Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences". Medical Education. 54 (12): 1180–1181. doi:10.1111/medu.14251. PMID 32438478.

- ↑ Favreau A. "Minnesota Virtual Clinic Medical Education Software". Regents of the University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- ↑ Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, Zendejas B, Szostek JH, Wang AT, et al. (September 2011). "Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 306 (9): 978–88. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1234. PMID 21900138.

- ↑ Jordan J, Jalali A, Clarke S, Dyne P, Spector T, Coates W (August 2013). "Asynchronous vs didactic education: it's too early to throw in the towel on tradition". BMC Medical Education. 13 (1): 105. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-105. PMC 3750828. PMID 23927420.

- ↑ Wray A, Bennett K, Boysen-Osborn M, Wiechmann W, Toohey S (2017-12-11). "Efficacy of an asynchronous electronic curriculum in emergency medicine education in the United States". Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions. 14: 29. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2017.14.29. PMC 5801323. PMID 29237247.

- ↑ Moro C, Štromberga Z, Raikos A, Stirling A (November 2017). "The effectiveness of virtual and augmented reality in health sciences and medical anatomy". Anatomical Sciences Education. 10 (6): 549–559. doi:10.1002/ase.1696. PMID 28419750. S2CID 25961448.

- ↑ Moro C, Štromberga Z, Stirling A (2017-11-29). "Virtualisation devices for student learning: Comparison between desktop-based (Oculus Rift) and mobile-based (Gear VR) virtual reality in medical and health science education". Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. 33 (6). doi:10.14742/ajet.3840. ISSN 1449-5554.

- ↑ Kononowicz AA, Woodham LA, Edelbring S, Stathakarou N, Davies D, Saxena N, et al. (July 2019). "Virtual Patient Simulations in Health Professions Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 21 (7): e14676. doi:10.2196/14676. PMC 6632099. PMID 31267981.

- ↑ Kovacevic P, Dragic S, Kovacevic T, Momcicevic D, Festic E, Kashyap R, et al. (June 2019). "Impact of weekly case-based tele-education on quality of care in a limited resource medical intensive care unit". Critical Care. 23 (1): 220. doi:10.1186/s13054-019-2494-6. PMC 6567671. PMID 31200761.

- ↑ van Houwelingen CT, Moerman AH, Ettema RG, Kort HS, Ten Cate O (April 2016). "Competencies required for nursing telehealth activities: A Delphi-study". Nurse Education Today. 39: 50–62. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2015.12.025. PMID 27006033.

- ↑ "indigenous-law-bulletin-vol7-issue-16-editorial-jan-feb-2010". doi:10.1163/2210-7975_hrd-1758-0046.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Cantone RE, Palmer R, Dodson LG, Biagioli FE (December 2019). "Insomnia Telemedicine OSCE (TeleOSCE): A Simulated Standardized Patient Video-Visit Case for Clerkship Students". MedEdPORTAL. 15 (1): 10867. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10867. PMC 7012306. PMID 32051850.

- ↑ Shortridge A, Steinheider B, Ciro C, Randall K, Costner-Lark A, Loving G (June 2016). "Simulating Interprofessional Geriatric Patient Care Using Telehealth: A Team-Based Learning Activity". MedEdPORTAL. 12 (1): 10415. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10415. PMC 6464453. PMID 31008195.

- ↑ "Medicine - Find My Pathway". Find My Pathway. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- ↑ (RACS), Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. "Pathways through specialty medical training". www.surgeons.org. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- 1 2 3 Brainard AH, Brislen HC (November 2007). "Viewpoint: learning professionalism: a view from the trenches". Academic Medicine. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 82 (11): 1010–4. doi:10.1097/01.acm.0000285343.95826.94. PMID 17971682.

- ↑ Goldie J (February 2000). "Review of ethics curricula in undergraduate medical education". Medical Education. Wiley. 34 (2): 108–19. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00607.x. PMID 10652063. S2CID 35027051.

- ↑ Steinberg ML (July 2008). "Introduction: health policy and health care economics observed". Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 18 (3): 149–51. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.01.001. PMID 18513623.

- 1 2 Schwartz RW, Pogge C (September 2000). "Physician leadership: essential skills in a changing environment". American Journal of Surgery. 180 (3): 187–92. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.579.8091. doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00481-5. PMID 11084127.

- ↑ Gee RE, Lockwood CJ (January 2013). "Medical education and health policy: what is important for me to know, how do I learn it, and what are the gaps?". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 121 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31827a099d. PMID 23262923. S2CID 35826385.

- 1 2 3 Patel MS, Davis MM, Lypson ML (February 2011). "Advancing medical education by teaching health policy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (8): 695–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1009202. PMID 21345098.

- 1 2 3 Heiman HJ, Smith LL, McKool M, Mitchell DN, Roth Bayer C (December 2015). "Health Policy Training: A Review of the Literature". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (1): ijerph13010020. doi:10.3390/ijerph13010020. PMC 4730411. PMID 26703657.

- 1 2 Avendano M, Kawachi I (2014-01-01). "Why do Americans have shorter life expectancy and worse health than do people in other high-income countries?". Annual Review of Public Health. 35: 307–25. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182411. PMC 4112220. PMID 24422560.

- ↑ Williams TR (July 2008). "A cultural and global perspective of United States health care economics". Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 18 (3): 175–85. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.01.005. PMID 18513627.

- ↑ Beyer DC, Mohideen N (July 2008). "The role of physicians and medical organizations in the development, analysis, and implementation of health care policy". Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 18 (3): 186–93. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.01.006. PMID 18513628.

- 1 2 Greysen SR, Wassermann T, Payne P, Mullan F (December 2009). "Teaching health policy to residents--three-year experience with a multi-specialty curriculum". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 24 (12): 1322–6. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1143-1. PMC 2787946. PMID 19862580.

- ↑ Patel MS, Lypson ML, Davis MM (September 2009). "Medical student perceptions of education in health care systems". Academic Medicine. 84 (9): 1301–6. doi:10.1097/acm.0b013e3181b17e3e. PMID 19707077.

- ↑ Catalanotti J, Popiel D, Johansson P, Talib Z (December 2013). "A pilot curriculum to integrate community health into internal medicine residency training". Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 5 (4): 674–7. doi:10.4300/jgme-d-12-00354.1. PMC 3886472. PMID 24455022.

- ↑ Rovner J (June 9, 2016). "This Med School Teaches Health Policy Along With The Pills". Retrieved December 13, 2016 – via NPR and Kaiser Health News (KHN).

- ↑ Shah SH, Clark MD, Hu K, Shoener JA, Fogel J, Kling WC, Ronayne J (October 2017). "Systems-Based Training in Graduate Medical Education for Service Learning in the State Legislature in the United States: Pilot Study". JMIR Medical Education. 3 (2): e18. doi:10.2196/mededu.7730. PMC 5663953. PMID 29042343.

- ↑ The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) (July 5, 2012). "ACGME Core Competencies". www.ecfmg.org. The Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ↑ Thomas P (2016). Curriculum Development for Medical Education-A Six Step Approach. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1421418520.

- ↑ Yew EH, Goh K (2016-12-01). "Problem-Based Learning: An Overview of its Process and Impact on Learning". Health Professions Education. 2 (2): 75–79. doi:10.1016/j.hpe.2016.01.004.

- ↑ Burgess A, Haq I, Bleasel J, Roberts C, Garsia R, Randal N, Mellis C (October 2019). "Team-based learning (TBL): a community of practice". BMC Medical Education. 19 (1): 369. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1795-4. PMC 6792232. PMID 31615507.

- ↑ Scalese RJ, Obeso VT, Issenberg SB (January 2008). "Simulation technology for skills training and competency assessment in medical education". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 23 (1): 46–9. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0283-4. PMC 2150630. PMID 18095044.

- ↑ Kilkie S, Harris P (2019-11-01). "P25 Using simulation to assess the effectiveness of undergraduate education". BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning. 5 (Suppl 2). doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2019-aspihconf.130.

- ↑ Majumder MA, Kumar A, Krishnamurthy K, Ojeh N, Adams OP, Sa B (2019-06-05). "An evaluative study of objective structured clinical examination (OSCE): students and examiners perspectives". Advances in Medical Education and Practice. 10: 387–397. doi:10.2147/amep.s197275. PMC 6556562. PMID 31239801.

- ↑ Onwudiegwu U (2018). "Osce: Design, Development and Deployment". Journal of the West African College of Surgeons. 8 (1): 1–22. PMC 6398515. PMID 30899701.

- ↑ Cömert M, Zill JM, Christalle E, Dirmaier J, Härter M, Scholl I (2016-03-31). Hills RK (ed.). "Assessing Communication Skills of Medical Students in Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE)--A Systematic Review of Rating Scales". PLOS ONE. 11 (3): e0152717. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1152717C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152717. PMC 4816391. PMID 27031506.

- ↑ Yazbeck Karam V, Park YS, Tekian A, Youssef N (December 2018). "Evaluating the validity evidence of an OSCE: results from a new medical school". BMC Medical Education. 18 (1): 313. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1421-x. PMC 6302424. PMID 30572876.

- 1 2 3 Memon I (2018). "Cadaver Dissection Is Obsolete in Medical Training! A Misinterpreted Notion". Medical Principles and Practice. 27 (3): 201–210. doi:10.1159/000488320. PMC 6062726. PMID 29529601.

- ↑ Tabas JA, Rosenson J, Price DD, Rohde D, Baird CH, Dhillon N (August 2005). "A comprehensive, unembalmed cadaver-based course in advanced emergency procedures for medical students". Academic Emergency Medicine. 12 (8): 782–5. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.004. PMID 16079434.

- ↑ Pais D, Casal D, Mascarenhas-Lemos L, Barata P, Moxham BJ, Goyri-O'Neill J (March 2017). "Outcomes and satisfaction of two optional cadaveric dissection courses: A 3-year prospective study" (PDF). Anatomical Sciences Education. 10 (2): 127–136. doi:10.1002/ase.1638. hdl:10400.17/3529. PMID 27483443. S2CID 24795098.

- ↑ Tavares MA, Dinis-Machado J, Silva MC (1 May 2000). "Computer-based sessions in radiological anatomy: one year's experience in clinical anatomy". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 22 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1007/s00276-000-0029-z. PMID 10863744. S2CID 24564960.

- 1 2 Korf HW, Wicht H, Snipes RL, Timmermans JP, Paulsen F, Rune G, Baumgart-Vogt E (1 February 2008). "The dissection course - necessary and indispensable for teaching anatomy to medical students". Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 190 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2007.10.001. PMID 18342138.

- ↑ Harden RM, Grant J, Buckley G, Hart IR (1 January 1999). "BEME Guide No. 1: Best Evidence Medical Education". Medical Teacher. 21 (6): 553–62. doi:10.1080/01421599978960. PMID 21281174.

- ↑ "MedEDPORTAL Author Handbook" (PDF). Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). 2009. pp. 2–4.

Further reading

- Bonner TN (2000). Becoming a physician: medical education in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, 1750-1945. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6482-7.

- Dunn MB, Jones C (March 2010). "Institutional logics and institutional pluralism: The contestation of care and science logics in medical education, 1967–2005". Administrative Science Quarterly. 55 (1): 114–49. doi:10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.114. hdl:2152/29317. S2CID 38016621.

- Gevitz N (2019). The DOs: osteopathic medicine in America. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2962-5.

- Holloway SW (1964). "Medical education in England, 1830–1858: A sociological analysis". History. 49 (167): 299–324. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1964.tb01104.x. JSTOR 24404427.

- Ludmerer KM (1999). Time to heal: American medical education from the turn of the century to the era of managed care. Oxford Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-19-535341-9.

- Papa FJ, Harasym PH (1999). Medical curriculum reform in North America, 1765 to the present: a cognitive science perspective (PDF). Vol. 74. Philadelphia: Academic Medicine. pp. 154–164. PMID 10065057.

- Parry N, Parry J (1976). The rise of the medical profession: a study of collective social mobility. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429400926. ISBN 978-0-429-40092-6.

- Porter R (1995). Disease, medicine and society in England, 1550-1860. Cambridge Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-521-55791-7.

- Rothstein WG (1987). American medical schools and the practice of medicine: A history. Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-19-536471-2.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Medical Education". |