Nerve block

| Nerve block | |

|---|---|

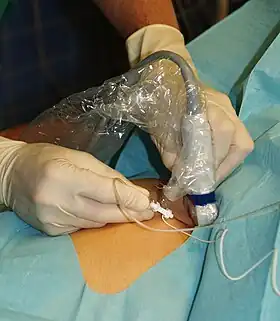

Ultrasound guided femoral nerve block | |

| ICD-9-CM | 04.81 |

| MeSH | D009407 |

Nerve block or regional nerve blockade is any deliberate interruption of signals traveling along a nerve, often for the purpose of pain relief. Local anesthetic nerve block (sometimes referred to as simply "nerve block") is a short-term block, usually lasting hours or days, involving the injection of an anesthetic, a corticosteroid, and other agents onto or near a nerve. Neurolytic block, the deliberate temporary degeneration of nerve fibers through the application of chemicals, heat, or freezing, produces a block that may persist for weeks, months, or indefinitely. Neurectomy, the cutting through or removal of a nerve or a section of a nerve, usually produces a permanent block. Because neurectomy of a sensory nerve is often followed, months later, by the emergence of new, more intense pain, sensory nerve neurectomy is rarely performed.

The concept of nerve block sometimes includes central nerve block, which includes epidural and spinal anaesthesia.[1]

Local anesthetic nerve block

Local anesthetic is often combined with other drugs to potentiate or prolong the analgesia produced by the nerve block. These adjuvants may include epinephrine, corticosteroids, opioids, ketamine, or alpha-adrenergic agonists. These blocks can be either single treatments, multiple injections over a period of time, or continuous infusions. A continuous peripheral nerve block can be introduced into a limb undergoing surgery – for example, a femoral nerve block to prevent pain in knee replacement.[2]

Local anesthetic nerve blocks are sterile procedures that are usually performed in an outpatient facility or hospital. The procedure can be performed with the help of ultrasound, fluoroscopy, or CT to guide the practitioner in the placement of the needle. A probe positioning system can be used to hold the ultrasound transducer steady. Electrical stimulation can provide feedback on the proximity of the needle to the target nerve. Historically, nerve blocks were performed blind or with electrical stimulation alone, but in contemporary practice, ultrasound or ultrasound with electrical stimulation is most commonly used.

It is unclear if the use of epinephrine in addition to lidocaine is safe for nerve blocks of fingers and toes due to insufficient evidence.[3] Another 2015 review states that it is safe in those who are otherwise healthy.[4] The addition of dexamethasone to a nerve block or if given intravenously for surgery can prolong the duration of an upper limb nerve block leading to reduction in postoperative opioid consumption[5]

Complications of nerve blocks most commonly include infection, bleeding, and block failure.[6] Nerve injury is a rare side effect occurring roughly 0.03-0.2% of the time.[7] The most significant complication of nerve blocks is local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) which can include neurologic and cardiovascular symptoms including cardiovascular collapse and death. Other side effects can result from the specific medications used; for example, transient tachycardia may result if epinephrine is administered in the block. It is important to note that despite these complications, procedures done under regional anesthesia (nerve block with or without intravenous sedation) carry a lower anesthetic risk than general anesthesia.

Neurolytic block

A neurolytic block is a form of nerve block involving the deliberate injury of a nerve by freezing or heating ("neurotomy") or the application of chemicals ("neurolysis").[8] These interventions cause degeneration of the nerve's fibers and temporary (a few months, usually) interference with the transmission of nerve signals. In these procedures, the thin protective layer around the nerve fiber, the basal lamina, is preserved so that, as a damaged fiber regrows, it travels within its basal lamina tube and connects with the correct loose end, and function may be restored. Surgical cutting of a nerve (neurectomy), severs these basal lamina tubes, and without them to channel the regrowing fibers to their lost connections, over time a painful neuroma or deafferentation pain may develop. This is why the neurolytic is usually preferred over the surgical block.[9]

The neurolytic block is sometimes used to temporarily reduce or eliminate pain in part of the body. Targets include[10]

- the celiac plexus, most commonly for cancer of the gastrointestinal tract up to the transverse colon, and pancreatic cancer, but also for stomach cancer, gall bladder cancer, adrenal mass, common bile duct cancer, chronic pancreatitis and active intermittent porphyria

- the splanchnic nerve, for retroperitoneal pain, and similar conditions to those addressed by the celiac plexus block but, because of its higher rate of complications, used only if the celiac plexus block is not producing adequate relief

- the hypogastric plexus, for cancer affecting the descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum, as well as cancers of the bladder, prostatic urethra, prostate, seminal vesicles, testicles, uterus, ovary and vaginal fundus

- the ganglion impar, for the perinium, vulva, anus, distal rectum, distal urethra, and distal third of the vagina

- the stellate ganglion, usually for head and neck cancer, or sympathetically mediated arm and hand pain

- the triangle of auscultation for pain from rib fractures and post thoracotomy using a rhomboid intercostal block

- the intercostal nerves, which serve the skin of the chest and abdomen

- and a dorsal root ganglion may be treated by targeting the root inside the subarachnoid cavity, most effective for pain in the chest or abdominal wall, but also used for other areas including arm/hand or leg/foot pain.

Neurectomy

Neurectomy is a surgical procedure in which a nerve or section of a nerve is severed or removed. Cutting a sensory nerve severs its basal lamina tubes, and without them to channel the regrowing fibers to their lost connections, over time a painful neuroma or deafferentation pain may develop. This is why the neurolytic is usually preferred over the surgical sensory nerve block.[9] This surgery is performed in rare cases of severe chronic pain where no other treatments have been successful, and for other conditions such as involuntary twitching and excessive blushing or sweating.[11]

A brief "rehearsal" local anesthetic nerve block is usually performed before the actual neurectomy to determine efficacy and detect side effects. The patient is typically under general anesthetic during the neurectomy, which is performed by a neurosurgeon.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Portable Pathophysiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. p. 149. ISBN 9781582554556.

- ↑ UCSD. Regional anesthesia

- ↑ Prabhakar, H; Rath, S; Kalaivani, M; Bhanderi, N (19 March 2015). "Adrenaline with lidocaine for digital nerve blocks". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD010645. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010645.pub2. PMC 7173752. PMID 25790261.

- ↑ Ilicki, J (4 August 2015). "Safety of Epinephrine in Digital Nerve Blocks: A Literature Review". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 49 (5): 799–809. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.05.038. PMID 26254284.

- ↑ Pehora, Carolyne; Pearson, Annabel ME; Kaushal, Alka; Crawford, Mark W; Johnston, Bradley (2017-11-09). "Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD011770. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011770.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6486015. PMID 29121400.

- ↑ Miller's anesthesia. Miller, Ronald D., 1939- (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 978-0-7020-5283-5. OCLC 892338436.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Hardman, David. "Nerve Injury After Peripheral Nerve Block: Best Practices and Medical-Legal Protection Strategies". Anethesiology news. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ↑ Scott Fishman; Jane Ballantyne; James P. Rathmell (January 2010). Bonica's Management of Pain. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1458. ISBN 978-0-7817-6827-6. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- 1 2 Williams JE (2008). "Nerve blocks: Chemical and physical neurolytic agents". In Sykes N, Bennett MI & Yuan C-S (ed.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 225–35. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- ↑ Atallah JN (2011). "Management of cancer pain". In Vadivelu N, Urman RD, Hines RL (eds.). Essentials of pain management. New York: Springer. pp. 597–628. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-87579-8. ISBN 978-0-387-87578-1.

- 1 2 McMahon, M. (2012, November 6). What is a Neurectomy? (O. Wallace, Ed.) Retrieved from wise GEEK: http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-a-neurectomy.htm#