Neuroendocrine adenoma middle ear

Neuroendocrine adenoma middle ear (NAME) is a tumor which arises from a specific anatomic site: middle ear.[1] NAME is a benign glandular neoplasm of middle ear showing histologic and immunohistochemical neuroendocrine and mucin-secreting differentiation (biphasic or dual differentiation).[2][3]

Classification

Neuroendocrine adenoma of the middle ear has gone by several different names, including middle ear adenoma, carcinoid tumor,[4] amphicrine adenoma,[5] adenocarcinoid, and adenomatoid tumor of middle ear.[6] The various names have created some confusion about this uncommon middle ear tumor. Regardless of the name applied, the middle ear anatomic site must be known or confirmed.

Signs and symptoms

This uncommon tumor accounts for less than 2% of all ear tumors. While patients present with symptoms related to the middle ear cavity location of the tumor, the tumor may expand into the adjacent structures (external auditory canal, mastoid bone, and eustachian tube).[7][8] Patients come to clinical attention with unilateral (one sided) hearing loss, usually associated with decreased auditory acuity, and particularly conductive hearing loss if the ossicular bone chain (middle ear bones) is involved.[2] Tinnitus (ringing), otitis media, pressure or occasionally ear discharge are seen. At the time of otoscopic exam, the tympanic membrane is usually intact, with a fluid level or mass noted behind the ear drum. Even though this is a "neuroendocrine" type tumor, there is almost never evidence of neuroendocrine function clinically or by laboratory examination.

Imaging findings

In general, an axial and coronal bone computed tomography study without contrast will yield the most information for this tumor. The tumor appears as a soft tissue mass usually within a well-aerated mastoid bone. The features of chronic otitis media are not usually seen. Bone invasion and destruction are usually not seen in this tumor which expands within the mesotympanum (middle ear cavity). Encasement of the ossicles is usually present. There may be an irregular margin at the periphery, especially if the tumor has been present for a long time, with associated bone remodeling.[2][7]

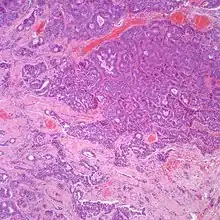

Pathology findings

At the time of surgery, the tumor tends to peel away from the adjacent bones, although not the ossicles. It is usually fragmented, soft, rubbery and white to gray-tan. Due to the anatomic confines of the region, tumors are usually <1 cm.[8] The tumors arise below the surface, are unencapsulated, and have an infiltrative pattern of growth, composed of many different patterns (glandular, trabecular, cords, festoons, single cells). The tumor shows duct-like structures with inner luminal, flattened cells and outer, basal, cuboidal cells. The cells may have an eccentrically placed nucleus. The nuclear chromatin distribution is "salt-and-pepper", giving a delicate, fine appearance. Nucleoli are small with inconspicuous mitoses. There may be secretions in the gland tumor. It is possible to see a concurrent cholesteatoma.[2]

Histochemistry

It is possible to see intracytoplasmic as well as luminal mucinous material highlighted by a Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) or Alcian blue stain.[9][10]

Immunohistochemistry

The tumor cells differential stain with markers for epithelial and neuroendocrine immunohistochemistry markers.

Electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy shows two distinct cell types:

- Type A: Apical dark cells with elongated microvilli and secretory mucus granules;

- Type B: Basal cells with cytoplasmic, solid, dense-core neurosecretory granules.

In a few areas, transitional forms with features of both cell types may be present.[12]

Diagnosis

From a pathology perspective, several tumors need to be considered in the differential diagnosis, including paraganglioma, ceruminous adenoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma, and meningioma.[2]

Management

The tumor must be removed with as complete a surgical excision as possible. In nearly all cases, the ossicular chain must be included if recurrences are to be avoided. Due to the anatomic site of involvement, facial nerve paralysis and/or paresthesias may be seen or develop; this is probably due to mass effect rather than nerve invasion. In a few cases, reconstructive surgery may be required. Since this is a benign tumor, no radiation is required. Patients experience an excellent long term outcome, although recurrences can be seen (up to 15%),[2] especially if the ossicular chain is not removed. Although controversial,[13] metastases are not seen in this tumor. There are reports of disease in the neck lymph nodes, but these patients have also had other diseases or multiple surgeries, such that it may represent iatrogenic disease.[2]

Epidemiology

Most individuals come to clinical attention during the 5th decade, although the age range is broad (20 to 80 years). There is an equal gender distribution.[7]

References

- 1 2 Devaney, Kenneth O.; Ferlito, Alfio; Rinaldo, Alessandra (2003). "Epithelial Tumors of the Middle Ear--Are Middle Ear Carcinoids Really Distinct from Middle Ear Adenomas?". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 123 (6): 678–682. doi:10.1080/00016480310001862. ISSN 0001-6489. PMID 12953765. S2CID 24772063.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Torske KR, Thompson LD (May 2002). "Adenoma versus carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: a study of 48 cases and review of the literature". Mod. Pathol. 15 (5): 543–55. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3880561. PMID 12011260.

- ↑ Hale, R J; McMahon, R F; Whittaker, J S (1991). "Middle ear adenoma: tumour of mixed mucinous and neuroendocrine differentiation". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 44 (8): 652–654. doi:10.1136/jcp.44.8.652. ISSN 0021-9746. PMC 496756. PMID 1890199.

- ↑ Stanley MW, Horwitz CA, Levinson RM, Sibley RK (1987). "Carcinoid tumors of the middle ear". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 87 (5): 592–600. doi:10.1093/ajcp/87.5.592. PMID 3578133.

- ↑ Ketabchi S, Massi D, Franchi A, Vannucchi P, Santucci M (2001). "Middle ear adenoma is an amphicrine tumor: why call it adenoma?". Ultrastruct Pathol. 25 (1): 73–8. doi:10.1080/019131201300004717. PMID 11297323. S2CID 218868445.

- ↑ Amble FR, Harner SG, Weiland LH, McDonald TJ, Facer GW (1993). "Middle ear adenoma and adenocarcinoma". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 109 (5): 871–6. doi:10.1177/019459989310900516. PMID 8247568. S2CID 23006159.

- 1 2 3 Leong K, Haber MM, Divi V, Sataloff RT (2009). "Neuroendocrine adenoma of the middle ear (NAME)". Ear Nose Throat J. 88 (4): 874–9. doi:10.1177/014556130908800412. PMID 19358129. S2CID 35987188.

- 1 2 Thompson L.D. (Sep 2005). "Neuroendocrine adenoma of the middle ear". Ear Nose Throat J. 84 (9): 560–1. doi:10.1177/014556130508400908. PMID 16261754. S2CID 13251769.

- ↑ Wassef M, et al. (Oct 1989). "Middle ear adenoma. A tumor displaying mucinous and neuroendocrine differentiation". Am J Surg Pathol. 13 (10): 838–47. doi:10.1097/00000478-198910000-00003. PMID 2782545. S2CID 6515115.

- ↑ Davies JE, Semeraro D, Knight LC, Griffiths GJ (1989). "Middle ear neoplasms showing adenomatous and neuroendocrine components". J Laryngol Otol. 103 (4): 404–7. doi:10.1017/S0022215100109065. PMID 2715695.

- ↑ Bold EL, Wanamaker JR, Hughes GB, Rhee CK, Sebek BA, Kinney SE (1995). "Adenomatous lesions of the temporal bone immunohistochemical analysis and theories of histogenesis". Am J Otol. 16 (2): 146–52. PMID 8572112.

- ↑ McNutt MA, Bolen JW (1985). "Adenomatous tumor of the middle ear. An ultrastructural and immunocytochemical study". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 84 (4): 541–7. doi:10.1093/ajcp/84.4.541. PMID 4036884.

- ↑ Ramsey MJ, Nadol JB, Pilch BZ, McKenna MJ (2005). "Carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: clinical features, recurrences, and metastases". Laryngoscope. 115 (9): 1660–6. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000175069.13685.37. PMID 16148713. S2CID 22056068.

Further reading

- Lester D. R. Thompson; Bruce M. Wenig (2011). Diagnostic Pathology: Head and Neck: Published by Amirsys. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 7:46–51. ISBN 978-1-931884-61-7.