Dyspareunia

| Dyspareunia | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Gynecology |

Dyspareunia is pain with sexual intercourse.[1] It can be recurrent or persistent in nature.[1] It is often associated with involuntary muscle spasms which prevent vaginal penetration, known as vaginismus.[1] It may result in poor self-esteem.[1]

Risk factors include young age, poor knowledge regarding sex, relationship problems, and physical abuse.[1] Other causes may include injury, vaginal atrophy, endometriosis, prolapse, vaginal yeast infections, herpes, lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and Behçet's.[1] Often multiple factors are involved.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on examination and medical history.[1]

Treatment depends on the primary underlying cause.[1] Generally it begins with education regarding the problem.[1] Either individual or couple counselling may help.[1] Anesthetic cream or estrogen cream may be useful in certain cases.[1]

Dyspareunia affects most women who have sex at some point in time.[1] It has been estimated to affect about 22% of women 6 to 12 months after having a baby.[2] The term is from the Greek for "difficult mating".[1]

Signs and symptoms

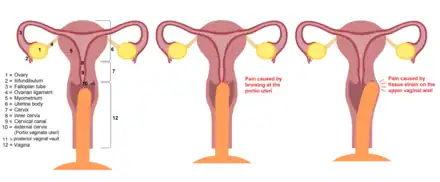

Those who experience pelvic pain upon attempted vaginal intercourse describe their pain in many ways. This reflects how many different and overlapping causes there are for dyspareunia.[3] The location, nature, and time course of the pain help to understand potential causes and treatments.[4]

Some describe superficial pain at the opening of the vagina or surface of the genitalia when penetration is initiated. Others feel deeper pain in the vault of the vagina or deep within the pelvis upon deeper penetration. Some feel pain in more than one of these places. Determining whether the pain is more superficial or deep is important in understanding what may be causing the pain.[5] Some patients have always experienced pain with intercourse from their very first attempt, while others begin to feel pain with intercourse after an injury or infection or cyclically with menstruation. Sometimes the pain increases over time.

Pain may distract from feeling pleasure and excitement. Both vaginal lubrication and vaginal dilation decrease. When the vagina is dry and undilated, penetration is more painful. Fear of being in pain can make the discomfort worse. Pain may continue despite the original source being removed, due to the learned expectation of pain. Fear, avoidance, and psychological distress around attempting intercourse can become large parts of the experience of dyspareunia.[6]

Physical examination of the vulva (external genitalia) may reveal clear reasons for pain including lesions, thin skin, ulcerations or discharge associated with vulvovaginal infections or vaginal atrophy. An internal pelvic exam may also reveal physical reasons for pain including lesions on the cervix or anatomic variation.[7]

When there are no visible findings on vulvar exam that would suggest a cause for superficial dyspareunia, a cotton-swab test may be performed. This is a test to assess for localized provoked vulvodynia.[6] A cotton tip applicator is applied at several points around the opening of the vagina; the patient reports the resulting pain on a scale from 0–10.

Causes

Women

The cause of the pain may be anatomic or physiologic, including but not limited to lesions of the vagina, retroversion of the uterus, urinary tract infection, lack of lubrication, scar tissue, abnormal growths, or tender pelvic sites.[8] Some cases may be psychosomatic, which can include fear of pain or injury, feelings of guilt or shame, ignorance of sexual anatomy and physiology, and fear of pregnancy.[9]

Common causes for discomfort on penetration include:

- Infections. Infections that mostly affect the labia, vagina, or lower urinary tract like yeast infections, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, urinary tract infections, or herpes tend to cause more superficial pain. Infections of the cervix, or fallopian tubes like pelvic inflammatory disease[10] tend to cause deeper pain.

- Cancer of the reproductive tract, including the ovaries, cervix, uterus, or vagina.

- Tissue Injury. Pain after trauma to the pelvis from injury, surgery or childbirth.[11]

- Anatomic variations. Hymenal remnants, vaginal septa,[12] thickened undilatable hymen,[12] hypoplasia of the introitus,[12] retroverted uterus[10] or uterine prolapse[10] can contribute to discomfort.

- Hormonal causes:

- Endometriosis[13] and adenomyosis

- Estrogen deficiency is a particularly common cause of sexual pain complaints related to vaginal atrophy among postmenopausal patients, and may be a result of similar changes in menstruating patients on hormonal birth control.[14] Estrogen deficiency is associated with lubrication inadequacy, which can lead to painful friction during intercourse. Vaginal dryness is often also reported alongside lactation.[15] Patients undergoing radiation therapy for pelvic malignancy often experience severe dyspareunia due to the atrophy of the vaginal walls and their susceptibility to trauma.

- Pelvic masses, including ovarian cysts,[16] tumors,[17] and uterine fibroids can cause deep pain.[10]

- Pain from bladder irritation: Dyspareunia is a symptom of interstitial cystitis (IC). Patients may struggle with bladder pain and discomfort during or after sex. For an IC patient with a penis, pain occurs at the moment of ejaculation and is focused at the tip of the penis. If the IC patient has a vagina, pain usually occurs the following day and is the result of painful, spasming pelvic floor muscles. Interstitial cystitis patients also struggle with urinary frequency and/or urinary urgency.

- Vulvodynia: Vulvodynia is a diagnosis of exclusion involving either generalized or localized vulvar pain most often described as burning without physical evidence of other causes on exam. Pain can be constant or only when provoked (as with intercourse). Localized provoked vulvodynia is the most recent terminology for what used to be called vulvar vestibulitis when the pain is localized to the vaginal opening.

- Conditions that affect the surface of the vulva including LSEA (lichen sclerosus et atrophicus), or xerosis (dryness, especially after the menopause). Vaginal dryness is sometimes seen in Sjögren's syndrome, an autoimmune disorder that characteristically attacks the exocrine glands that produce saliva and tears.

- Muscular dysfunction: For example, levator ani myalgia

- Psychological, such as vaginismus. Most vaginal pain disorders were officially discovered or coined during a time when rape was more normalized than it is now[18] (marital rape was only recognized as non-consensual by all 50 US states in 1993[19]). Some in the medical community are now starting to take into account factors like rape/sexual assault/ fear of rape/sexual harassment as strong enough psychological stressors to cause such pain disorders.[20]

Men

There are a number of physical factors that may cause sexual discomfort. Pain is sometimes experienced in the testicular or glans area of the penis immediately after ejaculation. Infections of the prostate, bladder, or seminal vesicles can lead to intense burning or itching sensations following ejaculation. Patients with interstitial cystitis may experience intense penis pain at the moment of ejaculation. Gonorrheal infections are sometimes associated with burning or sharp penile pains during ejaculation. Urethritis or prostatitis can make genital stimulation painful or uncomfortable. Anatomic deformities of the penis, such as exist in Peyronie's disease, may also result in pain during coitus. One cause of painful intercourse is due to the painful retraction of a too-tight foreskin, occurring either during the first attempt at intercourse or subsequent to tightening or scarring following inflammation or local infection.[17] Another cause of painful intercourse is due to tension in a short and slender frenulum, frenulum breve, as the foreskin retracts on entry to the vagina irrespective of lubrication. In one study frenulum breve was found in 50% of patients who presented with dyspareunia.[21] During vigorous or deep or tight intercourse or masturbation, small tears may occur in the preputial frenulum and can bleed and be very painful and induce anxiety, which can become chronic if left unresolved. If stretching fails to ease the condition, and uncomfortable levels of tension remain, a frenuloplasty procedure may be recommended. Frenuloplasty is an effective procedure, with a high chance of avoiding circumcision, giving good functional results and patient satisfaction.[22] The psychological effects of these conditions, while little understood, are real, and are visible in literature and art.[23]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

Dyspareunia is a condition that has many causes and is not a diagnosis of itself. It is combined with vaginismus into genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder in the DSM-5. Criteria for genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder include multiple episodes of difficulty with vaginal penetration, pain associated with intercourse attempts, anticipation of pain due to attempted intercourse, and tensing of the pelvis in response to attempted penetration. To meet criteria for this disorder, a patient must experience the symptoms for at least six months and experience "significant distress".[24]

The differential diagnosis for dyspareunia is long because of its complicated and multifactorial nature. Often there are physiologic conditions underlying the pain, as well as psychosocial components that must be assessed to find appropriate treatment. A differential diagnosis of underlying physical causes can be guided by whether the pain is deep or superficial:

- Superficial dyspareunia or vulvar pain: infection, inflammation, anatomic causes, tissue destruction, psychosocial factors, muscular dysfunction

- Superficial dyspareunia without visible exam findings: When no other physical cause is found the diagnosis of vulvodynia should be considered. Vaginal atrophy may also not be seen clearly on exam but commonly affects postmenopausal patients and is generally associated with estrogen deficiency.

- Deep dyspareunia or pelvic pain: endometriosis, ovarian cysts, pelvic adhesions, inflammatory diseases (interstitial cystitis, pelvic inflammatory disease), infections, congestion, psychosocial factors,

Treatment

The treatment for pain with intercourse depends on what is causing the pain. After proper diagnosis one or more treatments for specific causes may be necessary.

For example:

- For pain due to yeast or fungal infections, a clinician may prescribe mycogen cream (nystatin and triamcinolone acetonide), which treats both a yeast infection and associated painful inflammation and itching because it contains both an antifungal and a steroid.

- For pain that is likely due to post-menopausal vaginal dryness, estrogen treatment can be used.[25]

- For patients with diagnostic criteria for endometriosis, medications or surgery are possible options.[26]

In addition, the following may reduce discomfort with intercourse:

- Clearly explain to the patient what has happened, including identifying sites and causes of pain. Make clear that the pain, in almost all cases, disappears over time, or at least greatly lessens. If there is a partner, explain the causes and treatment and encourage them to be supportive.

- Encourage the patient to learn about her body, explore her own anatomy and learn how she likes to be caressed and touched.

- Encourage the couple to add pleasant, sexually exciting experiences to their regular interactions, such as bathing together (in which the primary goal is not cleanliness), or mutual caressing without intercourse. Such activities tend to increase both natural lubrication and vaginal dilation, both of which decrease friction and pain. Prior to intercourse, oral sex may relax and lubricate the vagina (provided both partners are comfortable with it).

- For those who have pain on deep penetration because of pelvic injury or disease, recommend a change in coital position to one with less penetration, such as missionary position. A device has also been described for limiting penetration.[27]

- Recommend water-soluble sexual or surgical lubricant during intercourse. Discourage petroleum jelly. Lubricant should be liberally applied (two tablespoons full) to both the penis and the orifice. A folded bath towel under the receiving partner's hips helps prevent spillage on bedclothes.

- Instruct the receiving partner to take the penis of the penetrating partner in their hand and control insertion themselves, rather than let the penetrating partner do it.

History

Etymology

The word "dyspareunia" comes from Greek δυσ-, dys- "bad" and πάρευνος, pareunos "bedfellow", meaning "badly mated".[12][28]

Classification

The previous Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the DSM-IV,[29] stated that the diagnosis of dyspareunia is made when the patient complains of recurrent or persistent genital pain before, during, or after sexual intercourse that is not caused exclusively by lack of lubrication or by vaginal spasm (vaginismus). After the text revision of the fourth edition of the DSM, a debate arose, with arguments to recategorize dyspareunia as a pain disorder instead of a sex disorder,[30] with Charles Allen Moser, a physician, arguing for the removal of dyspareunia from the manual altogether.[31] The most recent version, the DSM 5,[32] has grouped dyspareunia under the diagnosis of Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Lamont, John A. (2011). "Dyspareunia and Vaginismus". The Global Library of Women's Medicine. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10430.

- ↑ Banaei, Mojdeh; Kariman, Nourossadat; Ozgoli, Giti; Nasiri, Maliheh; Ghasemi, Vida; Khiabani, Azam; Dashti, Sareh; Mohamadkhani Shahri, Leila (2020-12-27). "Prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia: A systematic review and meta‐analysis". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 153 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13523. ISSN 0020-7292. PMID 33300122. S2CID 228088155. Archived from the original on 2023-10-22. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ Boyer, SC; Goldfinger, C; Thibault-Gagnon, S; Pukall, CF (2011). Management of female sexual pain disorders. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine. Vol. 31. pp. 83–104. doi:10.1159/000328810. ISBN 978-3-8055-9825-5. PMID 22005206.

- ↑ Katz, PT, PhD, Dr. Ditza (2020). "Painful Sex (Dyspareunia) Treatment | Women's Therapy Center". Archived from the original on 2021-01-18. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Boardman, Lori (2009). "Sexual Pain". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 52 (4): 682–90. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181bf4a7e. PMID 20393420.

- 1 2 Flanagan, E; Herron, KA; O'Driscoll, C; Williams, AC (20 October 2014). "Psychological Treatment for Vaginal Pain: Does Etiology Matter? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 12 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1111/jsm.12717. PMID 25329756.

- ↑ Boardman, Lori A.; Stockdale, Colleen K. (Dec 2009). "Sexual pain". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 52 (4): 682–90. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181bf4a7e. PMID 20393420.

- ↑ Yong, Paul J.; Williams, Christina; Yosef, Ali; Wong, Fontayne; Bedaiwy, Mohamed A.; Lisonkova, Sarka; Allaire, Catherine (2017-08-01). "Anatomic Sites and Associated Clinical Factors for Deep Dyspareunia". Sexual Medicine. 5 (3): e184–e195. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2017.07.001. ISSN 2050-1161. PMC 5562494. PMID 28778678.

- ↑ Tamparo, Carol (2011). Fifth Edition: Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- 1 2 3 4 familydoctor.org editorial staff. "Dyspareunia: Painful Sex for Women". Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ McDonald, Ea; Gartland, D; Small, R; Brown, Sj (2015-04-01). "Dyspareunia and childbirth: a prospective cohort study". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 122 (5): 672–679. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13263. ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 25605464.

- 1 2 3 4 Agnew AM (June 1959). "Surgery in the alleviation of dyspareunia". British Medical Journal. 1 (5136): 1510–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5136.1510. PMC 1993727. PMID 13651780.

- ↑ Denny E, Mann CH (July 2007). "Endometriosis-associated dyspareunia: the impact on women's lives". The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 33 (3): 189–93. doi:10.1783/147118907781004831. PMID 17609078.

- ↑ Smith, NK; Jozkowski, KN; Sanders, SA (February 2014). "Hormonal contraception and female pain, orgasm and sexual pleasure". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 11 (2): 462–70. doi:10.1111/jsm.12409. PMID 24286545.

- ↑ Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR, Kemmann E, Colburn DW, Swartzman L, Shelden R (July 1984). "Sexual expression and its determinants in the post-menopausal woman". Maturitas. 6 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(84)90062-8. PMID 6433154.

- ↑ David Delvin (23 October 2019). "Painful intercourse (dyspareunia)". Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- 1 2 Bancroft J (1989). Human sexuality and its problems (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-03455-8.

- ↑ "Vulvodynia: A Common and Under-Recognized Pain Disorder in Women and Female Adolescents -- Integrating Current Knowledge into Clinical Practice | Dannemiller Education Center". Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ Bergen, Raquel Kennedy, "Marital Rape" Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine on the site of the Applied Research Forum, National Electronic Network on Violence Against Women. Article dated March 1999. (Retrieved September 3, 2020.)

- ↑ McLean SA, Soward AC, Ballina LE, Rossi C, Rotolo S, Wheeler R, Foley KA, Batts J, Casto T, Collette R, Holbrook D, Goodman E, Rauch SA, Liberzon I (2012). "Acute severe pain is a common consequence of sexual assault". J Pain. 13 (8): 736–41. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2012.04.008. PMC 3437775. PMID 22698980.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Whelan. "Male dyspareunia due to short frenulum: an indication for adult circumcision". BMJ 1977; 24–31: 1633-4

- ↑ Dockray J, Finlayson A, Muir GH (May 2012). "Penile frenuloplasty: a simple and effective treatment for frenular pain or scarring". BJU International. 109 (10): 1546–50. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10678.x. PMID 22176714. S2CID 42381244.

- ↑ Douglas E. "JQuad". Archived from the original on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2023-10-18.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ Krychman, ML (March 2011). "Vaginal estrogens for the treatment of dyspareunia". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (3): 666–74. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02114.x. PMID 21091878.

- ↑ Vercellini P, Frattaruolo MP, Somigliana E, et al. (May 2013). "Surgical versus low-dose progestin treatment for endometriosis-associated severe deep dyspareunia II: effect on sexual functioning, psychological status and health-related quality of life". Human Reproduction. 28 (5): 1221–30. doi:10.1093/humrep/det041. PMID 23442755.

- ↑ Kompanje, EJ (October 2006). "Painful sexual intercourse caused by a disproportionately long penis: an historical note on a remarkable treatment devised by Guilhelmius Fabricius Hildanus (1560-1634)". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 35 (5): 603–5. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9057-z. PMID 17031589. S2CID 37484326.

- ↑ From δυσ-, dys- "bad" and πάρευνος, pareunos "bedfellow".

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994. ISBN 978-0-89042-062-1.

- ↑ Binik, YM (February 2005). "Should dyspareunia be retained as a sexual dysfunction in DSM-V? A painful classification decision". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 34 (1): 11–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.528.189. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-0998-4. PMID 15772767. S2CID 28497075.

- ↑ Moser, C (February 2005). "Dyspareunia: Another argument for removal". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 34 (1): 44–6, 57–61, author reply 63–7. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-7473-z. PMID 16092029. S2CID 12297902.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- The original text for this article is taken from a public domain CDC document PDF).

External links

- Sandra Risa Leiblum Sexual Pain Disorders - Dyspareunia Archived 2023-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Binik YM, Bergeron S, Khalifé S (2000). "Dyspareunia". In Leiblum SR, Rosen RC (eds.). Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 154–80. ISBN 978-1-57230-574-8.

| Look up dyspareunia in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Classification |

|---|