Paralytic shellfish poisoning

| Paralytic shellfish poisoning | |

|---|---|

| |

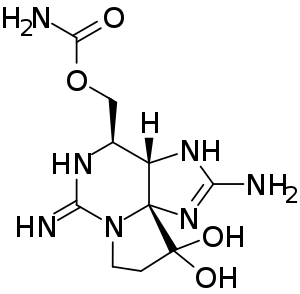

| The saxitoxin molecule shown in its unionized state. |

Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) is one of the four recognized syndromes of shellfish poisoning, which share some common features and are primarily associated with bivalve mollusks (such as mussels, clams, oysters and scallops). These shellfish are filter feeders and accumulate neurotoxins, chiefly saxitoxin, produced by microscopic algae, such as dinoflagellates, diatoms, and cyanobacteria.[1] Dinoflagellates of the genus Alexandrium are the most numerous and widespread saxitoxin producers and are responsible for PSP blooms in subarctic, temperate, and tropical locations.[2] The majority of toxic blooms have been caused by the morphospecies Alexandrium catenella, Alexandrium tamarense, Gonyaulax catenella and Alexandrium fundyense,[3] which together comprise the A. tamarense species complex.[4] In Asia, PSP is mostly associated with the occurrence of the species Pyrodinium bahamense.[5]

Also some pufferfish, including the chamaeleon puffer, contain saxitoxin, making their consumption hazardous.[6]

Pathophysiology

The toxins responsible for most shellfish poisonings are water insoluble, heat and acid-stable, and ordinary cooking methods do not eliminate the toxins. The principal toxin responsible for PSP is saxitoxin. Some shellfish can store this toxin for several weeks after a harmful algal bloom passes, but others, such as butter clams, are known to store the toxin for up to two years. Additional toxins are found, such as neosaxitoxin and gonyautoxins I to IV. All of them act primarily on the nervous system.

PSP can be fatal in extreme cases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Children are more susceptible. PSP affects those who come into contact with the affected shellfish by ingestion.[1] Symptoms can appear ten to 30 minutes after ingestion, and include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, tingling or burning lips, gums, tongue, face, neck, arms, legs, and toes.[1] Shortness of breath, dry mouth, a choking feeling, confused or slurred speech, and loss of coordination are also possible.

PSP in wild marine mammals

PSP has been implicated as a possible cause of sea otter mortality and morbidity in Alaska, as one of its primary prey items, the butter clam (Saxidonus giganteus) bioaccumulates saxitoxin as a chemical defense mechanism.[7] In addition, ingestion of saxitoxin-containing mackerel has been implicated in the death of humpback whales.[8]

Additional cases where PSP was suspected as the cause of death in Mediterranean monk seals (Monachus monachus) in the Mediterranean Sea[9] have been questioned due to lack of additional testing to rule out other causes of mortality.[10]

See also

- Amnesic shellfish poisoning

- Diarrheal shellfish poisoning

- Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning

- Harmful algal blooms (see "toxins")

- Ciguatera

- Cyanotoxin

- Dinoflagellate ecology and physiology (see "neurotoxins", "red tide", and "phosphate")

References

- 1 2 3 Clark, RF; Williams, SR; Nordt, SP; Manoguerra, AS (1999). "A review of selected seafood poisonings" (PDF). Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 26 (3): 175–84. PMID 10485519.

- ↑ Taylor, F. J. R.; Fukuyo, Y.; Larsen, J.; Hallegraeff, G. M. (2003). "Taxonomy of harmful dinoflagellates". In Hallegraeff, G.M.; Anderson, D.M.; Cembella, A.D. (eds.). Manual on Harmful Marine Microalgae. pp. 389–432. ISBN 92-3-103948-2.

- ↑ Cembella, A. D. (1998). "Ecophysiology and Metabolism of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins in Marine Microalgae". In Anderson, D. M.; Cembella, A. D.; Hallegraeff, G. M. (eds.). Physiological Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms. NATO ASI. Berlin: Springer. pp. 381–403. ISBN 978-3-662-03584-9.

- ↑ Balech, Enrique (1985). "The genus Alexandrium or Gonyaulax of the Tamarensis Group". In Anderson, Donald M.; White, Alan W.; Baden, Daniel G. (eds.). Toxic Dinoflagellates. New York: Elsevier. pp. 33–8. ISBN 978-0-444-01030-8.

- ↑ Azanza, Rhodora V.; Max Taylor, F. J. R. (2001). "Are Pyrodinium Blooms in the Southeast Asian Region Recurring and Spreading? A View at the End of the Millennium". AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment. 30 (6): 356–64. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-30.6.356. PMID 11757284. S2CID 20837132.

- ↑ Ngy, Laymithuna; Tada, Kenji; Yu, Chun-Fai; Takatani, Tomohiro; Arakawa, Osamu (2008). "Occurrence of paralytic shellfish toxins in Cambodian Mekong pufferfish Tetraodon turgidus: Selective toxin accumulation in the skin". Toxicon. 51 (2): 280–8. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.10.002. hdl:10069/22351. PMID 17996918.

- ↑ DeGange, Anthony R.; Vacca, M. Michele (November 1989). "Sea Otter Mortality at Kodiak Island, Alaska, during Summer 1987". Journal of Mammalogy. 70 (4): 836–8. doi:10.2307/1381723. JSTOR 1381723.

- ↑ Geraci, Joseph R.; Anderson, Donald M.; Timperi, Ralph J.; St. Aubin, David J.; Early, Gregory A.; Prescott, John H.; Mayo, Charles A. (1989). "Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) Fatally Poisoned by Dinoflagellate Toxin". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 46 (11): 1895–8. doi:10.1139/f89-238.

- ↑ Hernández, Mauro; Robinson, Ian; Aguilar, Alex; González, Luis Mariano; López-Jurado, Luis Felipe; Reyero, María Isabel; Cacho, Emiliano; Franco, José; López-Rodas, Victoria; Costas, Eduardo (1998). "Did algal toxins cause monk seal mortality?". Nature. 393 (6680): 28–9. Bibcode:1998Natur.393...28H. doi:10.1038/29906. hdl:10261/58748. PMID 9590687. S2CID 4425648.

- ↑ Van Dolah, Frances M. (2005). "Effects of Harmful Agal Blooms". In Reynolds, John E. (ed.). Marine Mammal Research: Conservation Beyond Crisis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 85–101. ISBN 978-0-8018-8255-5.