Patellar dislocation

| Patellar dislocation | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Kneecap dislocation, dislocated kneecap | |

| |

| X-ray showing a patellar dislocation, with the patella out to the side. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Knee is partly bent, painful and swollen[1][2] |

| Complications | Patella fracture, arthritis[3] |

| Usual onset | 10 to 17 years old[4] |

| Duration | Recovery within 6 weeks[5] |

| Causes | Bending the lower leg outwards when the knee is straight, direct blow to the patella when the knee is bent[1][2] |

| Risk factors | High riding patella, family history, loose ligaments[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, X-rays[2] |

| Treatment | Reduction, splinting, physical therapy, surgery[1] |

| Medication | Pain medication[3] |

| Prognosis | ~30% risk of recurrence[4] |

| Frequency | 6 per 100,000 per year[4] |

A patellar dislocation is a knee injury in which the patella (kneecap) slips out of its normal position.[5] Often the knee is partly bent, painful and swollen.[1][2] The patella is also often felt and seen out of place.[1] Complications may include a patella fracture or arthritis.[3]

A patellar dislocation typically occurs when the knee is straight and the lower leg is bent outwards when twisting.[1][2] Occasionally it occurs when the knee is bent and the patella is hit.[1] Commonly associated sports include soccer, gymnastics, and ice hockey.[2] Dislocations nearly always occur away from the midline.[2] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and supported by X-rays.[2]

Reduction is generally done by pushing the patella towards the midline while straightening the knee.[1] After reduction the leg is generally splinted in a straight position for a few weeks.[1] This is then followed by physical therapy.[1] Surgery after a first dislocation is generally of unclear benefit.[6][4] Surgery may be indicated in those who have broken off a piece of bone within the joint or in which the patella has dislocated multiple times.[4][5][3]

Patellar dislocations occur in about 6 per 100,000 people per year.[4] They make up about 2% of knee injuries.[1] It is most common in those 10 to 17 years old.[4] Rates in males and females are similar.[4] Recurrence after an initial dislocation occurs in about 30% of people.[4]

Signs and symptoms

People often describe pain as being "inside the knee cap." The leg tends to flex even when relaxed. In some cases, the injured ligaments involved in patellar dislocation do not allow the leg to flex almost at all.[2]

Risk factors

A predisposing factor is tightness in the tensor fasciae latae muscle and iliotibial tract in combination with a quadriceps imbalance between the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis muscles can play a large role, found, mainly, in women with higher level the physical activity.[7] Moreover, women with patellofemoral pain may show increased Q-angle compared with women without patellofemoral pain.

Another cause of patellar symptoms is lateral patellar compression syndrome, which can be caused from lack of balance or inflammation in the joints.[8] The pathophysiology of the kneecap is complex, and deals with the osseous soft tissue or abnormalities within the patellofemoral groove. The patellar symptoms cause knee extensor dysplasia, and sensitive small variations affect the muscular mechanism that controls the joint movements.[9]

24% of people whose patellas have dislocated have relatives who have experienced patellar dislocations.[2]

Athletic population

Patellar dislocation occurs in sports that involve rotating the knee. Direct trauma to the knee can knock the patella out of joint.

Anatomical factors

People who have larger Q angles tend to be more prone to having knee injuries such as dislocations, due to the central line of pull found in the quadriceps muscles that run from the anterior superior iliac spine to the center of the patella. The range of a normal Q angle for men ranges from <15 degrees and for females <20 degrees, putting females at a higher risk for this injury.[10] An angle greater than 25 degrees between the patellar tendon and quadriceps muscle can predispose a person to patellar dislocation.[11]

In patella alta, the patella sits higher on the knee than normal.[11] Normal function of the VMO muscle stabilizes the patella. Decreased VMO function results in instability of the patella.[2]

Forces

When there is too much tension on the patella, the ligaments will weaken and be susceptible to tearing ligaments or tendons due to shear force or torsion force, which then displaces the kneecap from its origination. Another cause that patellar dislocation can occur is when the trochlear groove that has been completely flattened is defined as trochlear dysplasia.[12] Not having a groove because the trochlear bone has flattened out can cause the patella to slide because nothing is holding the patella in place.

Mechanism of injury

Patellar dislocations occur by:

- A direct impact that knocks the patella out of joint

- A twisting motion of the knee, or ankle

- A sudden lateral cut [2]

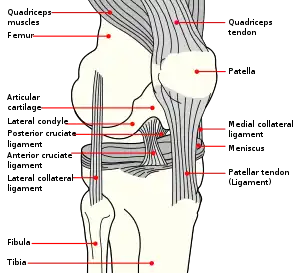

Anatomy of the knee

The patella is a triangular sesamoid bone which is embedded in tendon. It rests in the patellofemoral groove, an articular cartilage-lined hollow at the end of the thigh bone (femur) where the thigh bone meets the shin bone (tibia). Several ligaments and tendons hold the patella in place and allow it to move up and down the patellofemoral groove when the leg bends. The top of the patella attaches to the quadriceps muscle via the quadriceps tendon,[2] the middle to the vastus medialis obliquus and vastus lateralis muscles, and the bottom to the head of the tibia (tibial tuberosity) via the patellar tendon, which is a continuation of the quadriceps femoris tendon.[13] The medial patellofemoral ligament attaches horizontally in the inner knee to the adductor magnus tendon and is the structure most often damaged during a patellar dislocation. Finally, the lateral collateral ligament and the medial collateral ligament stabilize the patella on either side.[2] Any of these structures can sustain damage during a patellar dislocation.

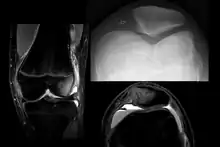

Diagnosis

To assess the knee, a clinician can perform the patellar apprehension test by moving the patella back and forth while the people flexes the knee at approximately 30 degrees.[14]

The people can do the patella tracking assessment by making a single leg squat and standing, or by lying on his or her back with knee extended from flexed position. A patella that slips laterally on early flexion is called the J sign, and indicates imbalance between the VMO and lateral structures.[15]

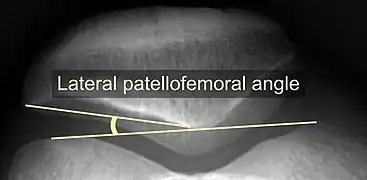

On X-ray, with skyline projections, dislocations are readily diagnosed. In borderline cases of subluxation, the following measurements can be helpful:

- The lateral patellofemoral angle, formed by:[16]

- A line connecting the most anterior points of the medial and lateral facets of the trochlea.

- A tangent to the lateral facet of the patella.

- With the knee in 20° flexed, this angle should normally open laterally.[16]

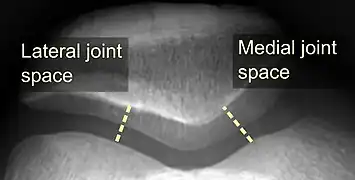

- The patellofemoral index is the ratio between the thickness of the medial joint space and the lateral joint space (L). With the knee 20° flexed, it should measure 1.6 or less.[16]

Prevention

The patella is a floating sesamoid bone held in place by the quadriceps muscle tendon and patellar tendon ligament. Exercises should strengthen quadriceps muscles such as rectus femoris, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis. However, tight and strong lateral quadriceps can be an underlying cause of patellar dislocation. If this is the case, it is advisable to strengthen the medial quadriceps, vastus medialis (VMO), and stretch the lateral muscles.[17] Exercises to strengthen quadriceps muscles include, but are not limited to, squats and lunges. Adding extra external support around the knee by using devices such as knee [orthotics] or athletic tape can help to prevent patellar dislocation and other knee-related injuries.[18] External supports, such as knee braces and athletic tape, work by providing movement in only the desired planes and help hinder movements that can cause abnormal movement and injuries. Women who wear high heels tend to develop short calf muscles and tendons. Exercises to stretch and strengthen calf muscles are recommended on a daily basis.[19]

Treatment

Two types of treatment options are typically available:

- Surgery

- Conservative treatment (rehabilitation and physical therapy)

Surgery may impede normal growth of structures in the knee, so doctors generally do not recommend knee operations for young people who are still growing.[20][21] There are also risks of complications, such as an adverse reaction to anesthesia or an infection.[20][21]

When designing a rehabilitation program, clinicians consider associated injuries such as chipped bones or soft tissue tears. Clinicians take into account the person's age, activity level, and time needed to return to work and/or athletics. Doctors generally only recommend surgery when other structures in the knee have sustained severe damage, or specifically when there is:[20]

- Concurrent osteochondral injury

- Continued gross instability

- Palpable disruption of the medial patellofemoral ligament and the vastus medialis obliquus

- High-level athletic demands coupled with mechanical risk factors and an initial injury mechanism not related to contact

Supplements like glucosamine and NSAIDs can be used to minimize bothersome symptoms.[14]

Rehabilitation

An effective rehabilitation program reduces the chances of re-injury and of other knee-related problems such as patellofemoral pain syndrome and osteoarthritis. Most patella dislocations are initially immobilized for the first 2–3 weeks to allow the stretched structures to heal. Rehabilitation focuses on maintaining strength and range of motion to reduce pain and maintain the health of the muscles and tissues around the knee joint.[14] The objective to any good rehabilitation program is to reduce pain, swelling and stiffness as well as increase range of motion. A common rehabilitation plan is to strengthen both the hip abductors, hip external rotators and the quadricep muscles. Commonly used exercises include isometric quadricep sets, side lying clamshells, leg dips with internal tibial rotation, etc. The idea is that because the medial side is most often stretched by the more common lateral dislocation, medial strengthening will add more stabilizing support. With progression more intense range of motion exercises are incorporated.[22]

Epidemiology

Rate in the United States are estimated 2.3 per 100,000 per year.[23] Rates for ages 10–17 were found to be about 29 per 100,000 persons per year, while the adult population average for this type of injury ranged between 5.8 and 7.0 per 100,000 persons per year.[24] The highest rates of patellar dislocation were found in the youngest age groups, while the rates declined with increasing ages. Females are more susceptible to patellar dislocation. Race is a significant factor for this injury, where Hispanics, African-Americans and Caucasians had slightly higher rates of patellar dislocation due to the types of athletic activity involved in: basketball (18.2%), soccer (6.9%), and football (6.9%), according to Brian Waterman.[23]

Lateral Patellar dislocation is common among the child population. Some studies suggest that the annual patellar dislocation rate in children is 43/100,000.[25] The treatment of the skeletally immature is controversial due to the fact that they are so young and are still growing. Surgery is recommended by some experts in order to repair the medial structures early, while others recommend treating it non operatively with physical therapy. If re-dislocation occurs then reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) is the recommended surgical option.[26]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ramponi, D (2016). "Patellar Dislocations and Reduction Procedure". Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal. 38 (2): 89–92. doi:10.1097/TME.0000000000000104. PMID 27139130.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dath, R; Chakravarthy, J; Porter, KM (2006). "Patella dislocations". Trauma. 8 (1): 5–11. doi:10.1191/1460408606ta353ra. ISSN 1460-4086.

- 1 2 3 4 Duthon, VB (February 2015). "Acute traumatic patellar dislocation". Orthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research : OTSR. 101 (1 Suppl): S59-67. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.12.001. PMID 25592052.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jain, NP; Khan, N; Fithian, DC (March 2011). "A treatment algorithm for primary patellar dislocations". Sports Health. 3 (2): 170–4. doi:10.1177/1941738111399237. PMC 3445142. PMID 23016004.

- 1 2 3 "Patellar Dislocation and Instability in Children (Unstable Kneecap)". OrthoInfo - AAOS. March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Toby O.; Donell, Simon; Song, Fujian; Hing, Caroline B. (26 February 2015). "Surgical versus non-surgical interventions for treating patellar dislocation" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD008106. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008106.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25716704. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ name=Ronaldovaldirbriani(2018)>Briani RV, De Oliveira SD, Pazzinatto MF, Ferreira AS, Ferrari D, de Azevedo FM (2016). "Delayed onset of electromyographic activity of the vastus medialis relative to the vastus lateralis may be related to physical activity levels in females with patellofemoral pain". Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 26: 137–142. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2015.10.012. hdl:11449/168461. PMID 26617182.

- ↑ Ficat, R. Paul.; Hungerford, David S. (1977). Disorders of the patello-femoral join. Baltimore: Williams Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-683-03200-0.

- ↑ Zaffagnini, Stefano.; Dejour, David.; Arendt, Elizabeth A. (Elizabeth Anne) (2010). Patellofemoral pain, instability, and arthritis : clinical presentation, imaging, and treatment. Heidelberg; New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-05423-5.

- ↑ Floyd, R. T. (2009). Manual of Structural Kinesiology. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-337643-1.

- 1 2 Buchner M, Baudendistel B, Sabo D, Schmitt H (March 2005). "Acute traumatic primary patella dislocation: long-term results comparing conservative and surgical treatment". Clin J Sport Med. 15 (2): 62–6. doi:10.1097/01.jsm.0000157315.10756.14. PMID 15782048.

- ↑ Dejour, H.; Walch, G.; Nove-Josserand, L.; Guier, C. (1994). "Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study". Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1007/bf01552649. PMID 7584171.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2012). Anatomy & physiology : the unity of form and function (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-07-337825-1.

- 1 2 3 Brukner, P.; Khan, K. (2006). Clinical Sports Medicine (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Family Practice Notebook > Patella Tracking Assessment Archived 18 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Scott Moses, last revised before 5/10/08

- 1 2 3 Saggin, Paulo Renato Fernandes; Saggin, Jose Idílio; Dejour, David (2012). "Imaging in Patellofemoral Instability". Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 20 (3): 145–151. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e3182553cfe. ISSN 1062-8592. PMID 22878655. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ Nomura, E.; Horiuchi, Y.; Kihara, M. (April 2000). "Medial patellofemoral ligament restraint in lateral patellar translation and reconstruction". Knee. 7 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1016/s0968-0160(00)00038-7. PMID 10788776.

- ↑ Gerrard, DF. (May 1998). "External knee support in rugby union. Effectiveness of bracing and taping". Sports Med. 25 (5): 313–7. doi:10.2165/00007256-199825050-00002. PMID 9629609.

- ↑ Abdulla, A. (December 2006). "Holiday review. Pills". CMAJ. 175 (12): 1575. doi:10.1503/cmaj.061382. PMC 1660600. PMID 17146100.

- 1 2 3 Shea KG, Nilsson K, Belzer J (2006). "Patellar dislocation in skeletally immature athletes". Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine. 14 (3): 188–196. doi:10.1053/j.otsm.2006.08.001.

- 1 2 Nikku R, Nietosvaara Y, Kallio PE, Aalto K, Michelsson JE (October 1997). "Operative versus closed treatment of primary dislocation of the patella. Similar 2-year results in 125 randomized patients". Acta Orthop Scand. 68 (5): 419–23. doi:10.3109/17453679708996254. PMID 9385238.

- ↑ Smith TO, Chester R, Cross J, Hunt N, Clark A, Donell ST. Rehabilitation following first-time patellar dislocation: a randomized controlled trial of purported vastus medialis obliquus muscle versus general quadriceps strengthening exercises. The Knee. 2015; 22: 313-320.

- 1 2 Waterman, BR.; Belmont, PJ.; Owens, BD. (March 2012). "Patellar dislocation in the United States: role of sex, age, race, and athletic participation". J Knee Surg. 25 (1): 51–7. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1286199. PMID 22624248. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ Fithian, DC.; Paxton, EW.; Stone, ML.; Silva, P.; Davis, DK.; Elias, DA.; White, LM. (2004). "Epidemiology and natural history of acute patellar dislocation". Am J Sports Med. 32 (5): 1114–21. doi:10.1177/0363546503260788. PMID 15262631.

- ↑ Sillanpää, Petri. "Treatment of Patellar Dislocation in Children" (PDF). patellofemoral.org. Patellofemoral Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Palmu, Sauli; Kallio, Pentti E.; Donell, Simon T.; Helenius, Ilkka; Nietosvaara, Yrjänä (1 March 2008). "Acute Patellar Dislocation in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized Clinical Trial". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 90 (3): 463–470. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00072. ISSN 1535-1386. PMID 18310694. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

- University of Connecticut: New England Musculoskeletal Institute – site concerning knee injury treatment options Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine