Dislocated jaw

| Dislocated jaw | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Temporal mandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation, dislocated mandible | |

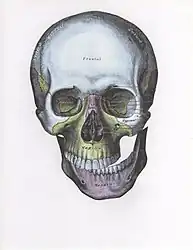

| |

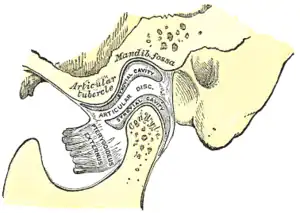

| Sagittal section of the articulation of the mandible. | |

| Specialty | ENT surgery |

| Symptoms | Inability to close the mouth, problems speaking and chewing, pain in front of the ear[1] |

| Complications | |Broken bones, injury to the external auditory canal, cranial nerve injuries[1] |

| Types | Anterior, posterior, superior, lateral[1] |

| Causes | Physical injury, over opening the jaw, connective tissue disorders[1] |

| Risk factors | Prior loss of teeth[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Mandible fracture, peritonsillar abscess, TMJ dysfunction, tetanus[1] |

| Treatment | Reduction[1] |

| Medication | Local anesthesia, procedural sedation, muscle relaxants[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally good[1] |

| Frequency | 2.5 per 10,000 per year[2] |

A dislocated jaw is when the condyle of the jaw bone is displaced from the joint surface of the temporal bone.[1] Symptoms may include inability to close the mouth, problems speaking and chewing, and pain in front of the ear.[1] Both sides are affected more commonly than a single side.[1] Associated complications may include |broken bones, injury to the external auditory canal, and cranial nerve injuries.[1]

It may occur due to physical injury, over opening of the jaw such as with yawning, and underlying structural problems such as connective tissue disorders.[1] Risk factors include prior loss of teeth.[1] Diagnosis is often based on symptoms, though may be supported by medical imaging.[1] Types include anterior (most common), posterior, superior, and lateral.[1]

Most commonly they can be treated with closed reduction.[1] This may require local anesthesia, procedural sedation, or muscle relaxants.[1] A number of techniques exist, including pushing down on the molars and than pushing backwards on the jaw.[1] If the dislocation has been long standing, open reduction may be required.[1] That with recurrent issues may have botulinum toxin injected.[1]

A dislocated jaw affects about 2 to 3 per 10,000 people per year and about 5% of the population at some point in time.[2] Techniques to reduce jaw locations have been documented as far back as 1500 BC.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms depend on the severity of injury and how long the person has been affected. Symptoms include a bite that feels “off” or abnormal, hard time talking or moving jaw, not able to close mouth completely, drooling due to not being able to shut mouth completely, teeth feel they are out of alignment, and a pain that becomes unbearable[3]

The immediate symptom can be a loud crunch noise occurring right up against the eardrum. This is rapidly followed by excruciating pain, particularly in the side where the dislocation occurred. Short-term symptoms can range from mild to chronic headaches, muscle tension or pain in the face, jaw and neck.

Long-term symptoms can result in sleep deprivation, tiredness/lethargy, frustration, bursts of anger or short fuse, difficulty performing everyday tasks, depression, social issues relating to difficulty talking, hearing sensitivity (particularly to high pitched sounds), tinnitus and pain when seated associated with posture while at a computer and reading books from general pressure on the jaw and facial muscles when tilting head down or up. And possible causing subsequent facial asymmetry.

In contrast, symptoms of a fractured jaw include bleeding coming from the mouth, unable to open the mouth wide without pain, bruising and swelling of the face, difficulty eating due to the constant pain, loss of feeling in the face (more specifically the lower lip) and lacks full range of motion of the jaw.[3]

Pathophysiology

There are four different positions of jaw dislocation: posterior, anterior, superior and lateral. The most common position is anterior, while the other types are rare. Anterior dislocation shifts the lower jaw forward if the mouth excessively opens. This type of dislocation may happen bilaterally or unilaterally after yawning. The muscles that are affected during anterior jaw dislocation are the masseter and temporalis which pull up on the mandible and the lateral pterygoid which relaxes the mandibular condyle. The condyle can get locked in front of the articular eminence. Posterior dislocation is possible for people who get injured by being punched in the chin. This dislocation will push the jaw back affecting the alignment of the mandibular condyle and mastoid. The external auditory canal may be fractured. Superior dislocations occur after being punched below the mandibular ramus as the mouth remains half-open. Since great force occurs in a punch, the angle of the jaw will be forced upward moving towards the condylar head. This can result in a fracture of the glenoid fossa and displacement of the condyle into the middle cranial fossa, potentially injuring the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves and the temporal lobe. Lateral dislocations move the mandibular condyle away from the skull and are likely to happen together with jaw fractures.[4][5]

Posterior, superior and lateral dislocations are uncommon injuries and usually result from high-energy trauma to the chin. By contrast, anterior dislocations are more often the result of low-energy trauma (e.g. tooth extraction) or secondary to a medical condition that affects the stability of the joint (e.g. seizures, ligamentous laxity, degeneration of joint capsule).

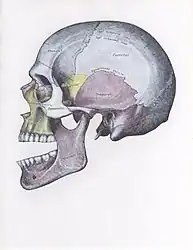

Side view of the skull with anterior dislocation of jaw.

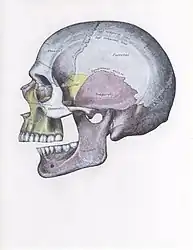

Side view of the skull with anterior dislocation of jaw. Side view of the skull with posterior dislocation of jaw.

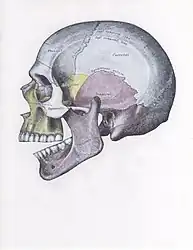

Side view of the skull with posterior dislocation of jaw. Side view of the skull with superior dislocation of jaw.

Side view of the skull with superior dislocation of jaw. Front view of the skull with lateral dislocation of jaw.

Front view of the skull with lateral dislocation of jaw.

Anatomy

The joint involved with jaw dislocation is the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). This joint is located where the mandibular condyles and the temporal bone meet.[6][4] Membranes that surround the bones help during the hinging and gliding of jaw movement. For the mouth to close it requires the following muscles: the masseter, temporalis, and medial pterygoid muscle. For the jaw to open it requires the lateral pterygoid muscle.[4]

Diagnosis

As with other joint dislocations, clinical history and examination are important for diagnosis. Commonly, plain and panoramic X-rays are used to determine the relative position of the mandibular condyle. If a complex or unusual injury is suspected, computed tomography is most reliable in diagnosing dislocation and possibly associated fractures or soft tissue injuries.

In case of dislocations resulting from high-energy trauma, attention must also be paid to possible other injuries, particularly blunt or indirect trauma to the skull and cervical spine. Acutely life-threatening conditions need to be ruled out or treated in first line. For superior jaw dislocation in particular, serious intracranial complications such as epidural hematoma are possible and must be recognized and managed to prevent disability or even death. Therefore, neurological status has to be examined in patients with complex dislocations involving temporal bone fractures. Hearing deficits on the injured side may indicate damage to structures of the ear.[7][8]

Bilateral anterior dislocation of the jaw

Bilateral anterior dislocation of the jaw.png.webp) Jaw dislocation following relocation

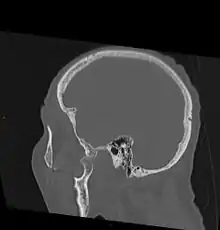

Jaw dislocation following relocation CT image demonstrating jaw dislocation

CT image demonstrating jaw dislocation

Treatment

As with most dislocated joints, a dislocated jaw can usually be successfully positioned into its normal position by a medical professional. The health care provider may be able to set it back into the correct position by manipulating the area back into its proper position. Local anesthetics, muscle relaxants, or in some cases sedation, may be needed to relax the strong jaw muscle. In more severe cases, surgery may be needed to reposition the jaw, particularly if repeated jaw dislocations have occurred.[9]

Techniques

A number of techniques exist, including pushing down on the molars and than pushing backwards on the jaw.[1] One technique which can be arrived out by the patient themselves is called the syringe method.[2] This is performed by placing an empty 5 or 10 mL syringe, oriented crosswise, on one side in the posterior portion of the patient's mouth, between the upper and lower molars.[1] The patient than bites down softly and roll the syringe backward and forward.[1]

Ongoing care

Following reduction a rigid cervical collar may be used to prevent reoccurrence.[1] The person should not open their mouth more than 2 cm for one to three weeks.[1] A soft diet is recommended for a few days to weeks.[1]

Epidemiology

Jaw dislocation is common for people who are in car, motorcycle or related accidents and also sports related activities. This injury does not pin point specific ages or genders because it could happen to anybody.[10] People who dislocate their jaw do not usually seek emergency medical care.[10] In most cases, jaw dislocations are acute and can be altered by minor manipulations.[5][11] It was reported from one study that over a seven-year period at an emergency medical site, with 100,000 yearly visits, there were only 37 patients that were seen for a dislocated jaw.[4]

See also

- Curb stomp

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Hillam, J; Isom, B (January 2022). "Mandible Dislocation". PMID 31747216.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Gottlieb, M; Long, B (13 July 2022). "Managing Temporomandibular Joint Dislocations". Annals of emergency medicine. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.05.031. PMID 35842342.

- 1 2 "Jaw - Broken or Dislocated". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- 1 2 3 4 Mandible Dislocation at eMedicine

- 1 2 Huang, I-Y.; Chen, C.-M.; Kao, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-M.; Wu, C.-W. (2011). "Management of long-standing mandibular dislocation". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 40 (8): 810–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2011.02.031. PMID 21474286.

- ↑ Parida, Satyen; Allampalli, Varshad; Krishnappa, Sudeep (2011). "Catatonia and jaw dislocation in the postoperative period with epidural morphine". Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 55 (2): 184–6. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.79904. PMC 3106396. PMID 21712880.

- ↑ Sharma, N. K., Singh, A. K., Pandey, A., Verma, V., & Singh, S. (2015). Temporomandibular joint dislocation. National Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery, 6(1), 16–20. http://doi.org/10.4103/0975-5950.168212 Archived 2022-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Management of Traumatic Dislocation of the Mandibular Condyle into the Middle Cranial Fossa" (PDF). www.cda-adc.ca. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2018-03-23.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Jaw - broken or dislocated

- 1 2 "Dislocated jaw symptoms, diagnosis & treatment". Intuition Communication. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2012-02-09.

- ↑ Mayer, Leo (1933). "Recurrent dislocation of the jaw". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 15 (4): 889–96. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26.

External links

- 7 relocation techniques Archived 2022-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |