Picoplankton

Picoplankton is the fraction of plankton composed by cells between 0.2 and 2 μm that can be either prokaryotic and eukaryotic phototrophs and heterotrophs:

- photosynthetic

- heterotrophic

They are prevalent amongst microbial plankton communities of both freshwater and marine ecosystems. They have an important role in making up a significant portion of the total biomass of phytoplankton communities.

Classification

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

In general, plankton can be categorized on the basis of physiological, taxonomic, or dimensional characteristics. Subsequently, a generic classification of a plankton includes:

- Bacterioplankton

- Phytoplankton

- Zooplankton

However, there is a simpler scheme that categorizes plankton based on a logarithmic size scale:

- Macroplankton (200–2000 μm)

- Micro-plankton (20–200 μm)

- Nanoplankton (2–20 μm)

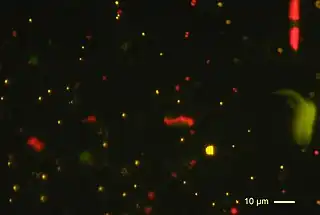

This was even further expanded to include picoplankton (0.2-2 μm) and fem-toplankton (0.02-0.2 μm), as well as net plankton, ultraplankton. Now that picoplankton have been characterized, they have their own further subdivisions such as prokaryotic and eukaryotic phototrophs and heterotrophs that are spread throughout the world in various types of lakes and tropic states. In order to differentiate between autotrophic picoplankton and heterotrophic picoplankton, the autotrophs could have photosynthetic pigments and the ability to show autofluorescence, which would allow for their enumeration under epifluorescence microscopy. This is how minute eukaryotes first became known.[1]

Overall, picoplankton play an essential role in oligotrophic dimicitc lakes because they are able to produce and then accordingly recycle dissolved organic matter (DOM) in a very efficient manner under circumstance when competition of other phytoplankters is disturbed by factors such as limiting nutrients and predators. Picoplankton are responsible for the most primary productivity in oligotrophic gyres, and are distinguished from nanoplankton and microplankton.[2] Because they are small, they have a greater surface to volume ratio, enabling them to obtain the scarce nutrients in these ecosystems. Furthermore, some species can also be mixotrophic. The smallest of cells (200 nm) are on the order of nanometers, not picometers. The SI prefix pico- is used quite loosely here, as nanoplankton and microplankton are only 10 and 100 times larger, respectively, although it is somewhat more accurate when considering the volume rather than the length.

Role in ecosystems

Picoplankton contribute greatly to the biomass and primary production in both marine and freshwater lake ecosystems. In the ocean, the concentration of picoplankton is 105–107 cells per millilitre of ocean water.[3] Algal picoplankton is responsible for up to 90 percent of the total carbon production daily and annually in oligotrophic marine ecosystems.[4] The amount of total carbon production by picoplankton in oligotrophic freshwater systems is also high, making up 70 percent of total annual carbon production.[4] Marine picoplankton make up a higher percentage of biomass and carbon production in zones that are oligotrophic, like the open ocean, versus regions near the shore that are more nutrient rich.[4][5] Their biomass and carbon production percentage also increases as the depth into the euphotic zone increases. This is due to their use of photopigments and efficiency at using blue-green light at these depths.[4] Picoplankton population densities do not fluctuate throughout the year except in a few cases of smaller lakes where their biomass increases as the temperature of the lake water increases.[5]

Picoplankton also play an important role in the microbial loop of these systems by aiding in providing energy to higher trophic levels.[4] They are grazed by a various number of organisms such as flagellates, ciliates, rotifers and copepods. Flagellates are their main predator due to their ability to swim towards picoplankton in order to consume them.[5]

Oceanic picoplankton

Picoplankton are important in nutrient cycling in all major oceans, where they exist in their highest abundances. They have many features that allow them to survive in these oligotrophic (low-nutrient) and low-light regions, such as the use several nitrogen sources, including nitrate, ammonium, and urea.[6] Their small size and large surface area allows for efficient nutrient acquisition, incident light absorption, and organism growth.[7] A small size also allows for minimal metabolic maintenance.[8]

Picoplankton, specifically phototrophic picoplankton, play a significant role in the carbon production of open oceanic environments, which largely contributes to the global carbon production.[6] Their carbon production contributes to at least 10% of global aquatic net primary productivity.[7] High primary productivity contributions are made in both oligotrophic and deep zones in oceans.[6] Picoplankton are dominant in biomass in open ocean regions.[9]

Picoplankton also form the base of aquatic microbial food webs and are an energy source in the microbial loop. All trophic levels in a marine food web are affected by picoplankton carbon production and the gain or loss of picoplankton in the environment, especially in oligotrophic conditions.[8] Marine predators of picoplankton include heterotrophic flagellates and ciliates.[6] Protozoa are a dominant predator of picoplankton.[8] Picoplankton are often lost through processes such as grazing, parasitism, and viral lysis.[8]

Measurement

Marine scientists have slowly begun to understand in the last 10 or 15 years the importance of even the smallest subdivisions of plankton and their role in aquatic food webs and in organic and inorganic nutrient recycling. Therefore, being able to accurately measure the biomass and size distribution of picoplankton communities has now become rather essential. Two of the prevalent methods used to identify and enumerate picoplankton are fluorescence microscopy and visual counting. However, both methods are outdated because of their time-consuming and inaccurate nature. As a result, newer, faster, and more accurate methods have emerged lately, including flow cytometry and image-analyzed fluorescence microscopy. Both techniques are efficient in measuring nano plankton and auto-fluorescing phototrophic picoplankton. However, measuring very minute size ranges of picoplankton has often proven to be difficult to measure, which is why Charge-coupled devices (CCD) and video cameras are now being used to measure small picoplankton, although a slow-scan CCD-based camera is more effective at detecting and sizing tiny particles such as bacteria that is fluorochrome-stained.[10]

See also

- Plankton § Size groups

References

- ↑ Callieri, Cristiana; Stockner, John G. (1 February 2002). "Freshwater autotrophic picoplankton: a review". Journal of Limnology. 61 (1): 1–14. doi:10.4081/jlimnol.2002.1.

- ↑ Vershinin, Alexander. "Phytoplankton in the Black Sea". Russian Federal Children Center Orlyonok.

- ↑ Schmidt, T. M.; DeLong, E. F.; Pace, N. R. (1991-07-01). "Analysis of a marine picoplankton community by 16S rRNA gene cloning and sequencing". Journal of Bacteriology. 173 (14): 4371–4378. doi:10.1128/jb.173.14.4371-4378.1991. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 208098. PMID 2066334.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stockner, John G.; Antia, Naval J. (April 14, 1986). "Algal Picoplankton from Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems: A Multidisciplinary Perspective". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 43 (12): 2472–2503. doi:10.1139/f86-307.

- 1 2 3 Fogg, G.E. (April 28, 1995). "Some comments on picoplankton and its importance in the pelagic ecosystem" (PDF). Aquat Microb Ecol. 9: 33–39. doi:10.3354/ame009033.

- 1 2 3 4 Stockner, John G (1988). "Phototrophic picoplankton: An overview from marine and freshwater ecosystems". Limnology and Oceanography. 4 (33): 765–775. Bibcode:1988LimOc..33..765S. doi:10.4319/lo.1988.33.4part2.0765.

- 1 2 Agawin, Nona S; Duarte, Carlos M; Augusti, Susana (2000). "Nutrient and temperature control of the contribution of picoplankton to phytoplankton biomass and production". Limnology and Oceanography. 3 (45): 591–600. Bibcode:2000LimOc..45..591A. doi:10.4319/lo.2000.45.3.0591.

- 1 2 3 4 Callieri, Cristiana; Stockner, John G (2002). "Freshwater autotrophic picoplankton: a review". Journal of Limnology. 1 (61): 1–14. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.3454. doi:10.4081/jlimnol.2002.1.

- ↑ Moon-van der Staay, Seung Yeo; De Wachter, Rupert; Vaulot, Daniel (February 2001). "Oceanic 18S rDNA sequences from picoplankton reveal unsuspected eukaryotic diversity". Nature. 409 (6820): 607–610. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..607M. doi:10.1038/35054541. PMID 11214317. S2CID 4362835.

- ↑ Viles, C L; Sieracki, M E (February 1992). "Measurement of marine picoplankton cell size by using a cooled, charge-coupled device camera with image-analyzed fluorescence microscopy". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 58 (2): 584–592. doi:10.1128/AEM.58.2.584-592.1992. PMC 195288. PMID 1610183.