Porencephaly

| Porencephaly | |

|---|---|

| |

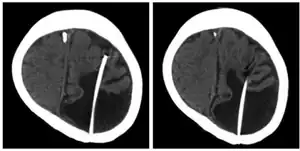

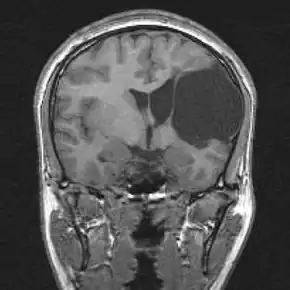

| Porencephalic cyst in the left parietooccipital and right frontal area.[1] | |

| Specialty | Neurology, medical genetics |

Porencephaly is an extremely rare cephalic disorder involving encephalomalacia.[2] It is a neurological disorder of the central nervous system characterized by cysts or cavities within the cerebral hemisphere.[3] Porencephaly was termed by Heschl in 1859 to describe a cavity in the human brain.[4] Derived from Greek roots, the word porencephaly means 'holes in the brain'.[5] The cysts and cavities (cystic brain lesions) are more likely to be the result of destructive (encephaloclastic) cause, but can also be from abnormal development (malformative), direct damage, inflammation, or hemorrhage.[6] The cysts and cavities cause a wide range of physiological, physical, and neurological symptoms.[7] Depending on the patient, this disorder may cause only minor neurological problems, without any disruption of intelligence, while others may be severely disabled or face death before the second decade of their lives. However, this disorder is far more common within infants, and porencephaly can occur both before or after birth.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Patients diagnosed with porencephaly display a variety of symptoms, from mild to severe effects on the patient. Patients with severe cases of porencephaly suffer epileptic seizures and developmental delays, whereas patients with a mild case of porencephaly display little to no seizures and healthy neurodevelopment. Infants with extensive defects show symptoms of the disorder shortly after birth, and the diagnosis is usually made before the age of 1.[3][8]

The following text lists out common signs and symptoms of porencephaly in affected individuals along with a short description of certain terminologies.[3][7][8][9]

- Degenerative or non-degenerative cavities or cysts

- Delayed growth and development

- Spastic paresis – weakness or loss in voluntary movement

- Contractures – painful shortening of muscles affecting motion

- Hypotonia – reduced muscle strength

- Epileptic seizures and epilepsy – multiple symptoms that involve sudden muscle spasms and loss of consciousness

- Macrocephaly – condition where head circumference is larger compared to other children of a certain age

- Microcephaly – condition where head circumference is smaller compared to other children of a certain age

- Hemiplegia – paralysis of appendages

- Tetraplegia – paralysis of limb leading to loss of function

- Intellectual and cognitive disability

- Poor or absent speech development

- Hydrocephalus – accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain

- Mental retardation

- Poor motor control, abnormal movements of appendages

- Cerebral palsy – a motor condition causing movement disabilities

- Blood vascular diseases such as intracerebral hemorrhage and cerebral infarction.

- Cerebral white-matter lesions

Cause

Porencephaly is a rare disorder. The exact prevalence of porencephaly is not known; however, it has been reported that 6.8% of patients with cerebral palsy or 68% of patients with epilepsy and congenital vascular hemiparesis have porencephaly.[6] Porencephaly has a number of different, often unknown, causes including absence of brain development and destruction of brain tissue. With limited research, the most commonly regarded cause of porencephaly is disturbances in blood circulation, ultimately leading to brain damage.[7] However, a number of different and multiple factors such as abnormal brain development or damage to the brain tissue can also affect the development of porencephaly.[3]

The following text lists out potential risk factors of developing porencephaly and porencephalic cysts and cavities along with brief description of certain terminologies.[4][7][8][10]

- Lack of oxygen and blood supply to the brain leading to internal bleeding

- Cerebral degeneration – loss of neuron structure and function

- Maternal cardiac arrest

- Trauma during pregnancy

- Abdominal trauma

- Pathogenic infection

- Accidents

- Abnormal brain development during birth

- Vascular thrombosis – blood clot formation within blood vessels

- Hemorrhage – loss of blood outside of the circulatory system

- Brain contusion or injury

- Multifocal cerebrovascular insufficiency

- Placental bleeding – prevention of oxygen and blood supply to infant brain

- Maternal toxemia – toxin within circulatory system of mother that is transferred to fetus, causing brain damage

- Cerebral hypoxia – reduced oxygen concentration within blood system

- Vascular occlusion – blood clotting of vessels

- Cystic periventricular leukomalacia

- Cerebral atrophy – decrease in neuron number and size and loss of brain mass

- Chronic lung disease

- Male gender

- Endotoxins

- Prenatal and postnatal encephalitis and meningitis

- Drug abuse of mother

Cysts or cavities can occur anywhere within the brain and the locations of these cysts depend highly on the patient. Cysts can develop in the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, forebrain, hindbrain, temporal lobe, or virtually anywhere in the cerebral hemisphere.[8]

Genetics

From recent studies, de novo and inherited mutations in the gene COL4A1, suggesting genetic predisposition within the family, that encodes type IV collagen α1 chain has shown to be associated with and present in patients with porencephaly. COL4A1 mutation causes a variety of phenotypes, including porencephaly, infantile hemiplegia, and cerebral small vessel diseases involving both stroke and infarction.[7] Abnormal gene expression of COL4A1 can contribute to the development of porencephaly. COL4A1 gene expresses a type IV collagen (basement protein) that is present in all tissue and blood vessels and is extremely important for the structural stability of vascular basement membranes. The COL4A1 protein provides a strong layer around blood vessels.[11] The mutation can weaken the blood vessels within the brain, elevating the probability of a hemorrhage, and eventually promoting internal bleeding then leading to porencephaly during neurodevelopment of infantile stage.[7] Therefore, the formation of cavities can be a result of hemorrhages which promote cerebral degeneration.[11] In a mouse model, mouse with COL4A1 mutations displayed cerebral hemorrhage, porencephaly, and abnormal development of vascular basement membranes, such as uneven edges, inconsistent shapes, and highly variable thickness.[7] Purposely causing a mutation in the COL4A1 gene caused several mouse to develop cerebral hemorrhage and porencephaly-like diseases. Though, there is no direct correlation between mutations of the COL4A1 gene, it appears that it has an influential effect on the development of porencephaly.[12][13][14]

Another genetic mutation, factor V G1691A mutation, has been reported to show possible association to the development of porencephaly. A mutation in factor V G1691A increases the risk of thrombosis, blood clots, in neonates, infants, and children.[6] Therefore, 76 porencephalic and 76 healthy infants were investigated for factor V G1691A mutation along with other different prothrombotic risk factors. The results indicated that there was higher prevalence of the factor V G1691A mutation in the porencephalic patient group. The prediction that childhood porencephaly is caused by hypercoagulable state, a condition where one has a higher chance of developing blood clots, was supported by the significance of the factor V G1691A mutation. Also, pregnant women in hypercoagulable state can cause the fetus to have the same risks, therefore possibly causing fetal loss, brain damage, lesions, and infections that lead to porencephaly. However, other different prothrombotic risk factors individually did not reach statistical significance to link it to the development of porencephaly, but a combination of multiple prothrombotic risk factors in the porencephaly group was significant. Overall, factor V G1691A mutation has been linked to the development of porencephaly. However, this one mutation is not the cause of porencephaly, and whether further prothrombiotic risk factors are associated with porencephaly still remains unknown.[6]

Cocaine and other street drugs

In utero exposure to cocaine and other street drugs can lead to porencephaly.[15]

Diagnostics

The presence of porencephalic cysts or cavities can be detected using trans-illumination of the skull of infant patients. Porencephaly is usually diagnosed clinically using the patients and families history, clinical observations, or based on the presence of certain characteristic neurological and physiological features of porencephaly. Advanced medical imaging with computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or with ultrasonography can be used as a method to exclude other possible neurological disorders. The diagnosis can be made antenatally with ultrasound. Other assessments include memory, speech, or intellect testing to help further determine the exact diagnose of the disorder.[3]

Treatments

There is no cure for porencephaly because of the limited resources and knowledge about the neurological disorder. However, several treatment options are available. Treatment may include physical therapy, rehabilitation, medication for seizures or epilepsy, shunt (medical), or neurosurgery (removal of the cyst).[3] According to the location, extent of the lesion, size of cavities, and severity of the disorder, combinations of treatment methods are imposed. In porencephaly patients, patients achieved good seizure control with appropriate drug therapy including valproate, carbamazepine, and clobazam.[7][8] Also, anti-epileptic drugs served as another positive method of treatment.[8]

Prognosis

The severity of the symptoms associated with porencephaly varies significantly across the population of those affected, depending on the location of the cyst and damage of the brain. For some patients with porencephaly, only minor neurological problems may develop, and those patients can live normal lives. Therefore, based on the level of severity, self-care is possible, but for the more serious cases lifelong care will be necessary.[3] For those that have severe disability, early diagnosis, medication, participation in rehabilitation related to fine-motor control skills, and communication therapies can significantly improve the symptoms and ability of the patient with porencephaly to live a normal life. Infants with porencephaly that survive, with proper treatment, can display proper communication skills, movement, and live a normal life.

Research

Under the United States federal government, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and National Institute of Health are involved in conducting and supporting research related to normal and abnormal brain and nervous system development. Information gained from the research is used to develop understanding of the mechanism of porencephaly and used to offer new methods of treatment and prevention for developmental brain disorders such as porencephaly.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Choi, MJ; Oh, YS; Park, SJ; Kim, JH; Shin, JI (1 July 2012). "Cerebral salt wasting treated with fludrocortisone in a 17-year-old boy". Yonsei medical journal. 53 (4): 859–62. doi:10.3349/ymj.2012.53.4.859. PMID 22665358.

- ↑ Gul A, Gungorduk K, Yildirim G, Gedikbasi A, Ceylan Y (2009). "Prenatal diagnosis of porencephaly secondary to maternal carbon monoxide poisoning". Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 279 (5): 697–700. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0776-3. PMID 18777036. S2CID 26880094.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Parker, J. (2004). The official parent's sourcebook on porencephaly: A revised and updated directory for the internet age. ICON Health Publications.

- 1 2 Hirowatari C., Kodama R., Sasaki Y., Tanigawa Y., Fujishima J.; et al. (2012). "Porencephaly in a Cynomolgus Monkey ( Macaca Fascicularis )". Journal of Toxicologic Pathology. 25 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1293/tox.25.45. PMC 3320157. PMID 22481858.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Maria Gieron-Korthals; José Colón (2005). "Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in infants: new challenges". Fetal and Pediatric Pathology. Taylor & Francis. 24 (2).

... Porencephaly (Greek for 'holes in the brain') are hemispheric cavitary lesions that typically communicate with the ventricular system....

- 1 2 3 4 Debus O., Kosch A., Strater R., Rossi R., Nowak-Gottl U. (2004). "The Factor V G1691A Mutation is a Risk for Porencephaly: A Case-control Study". Annals of Neurology. 56 (2): 287–290. doi:10.1002/ana.20184. PMID 15293282. S2CID 33972596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yoneda Y., Haginoya K., Arai H., Yamaoka S., Tsurusaki Y.; et al. (2012). "De Novo and Inherited Mutations in COL4A2, Encoding the Type IV Collagen α2 Chain Cause Porencephaly". Am J Hum Genet. 90 (1): 86–90. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.016. PMC 3257897. PMID 22209246.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shimizu M., Maeda T., Izumi T. (2012). "The Differences in Epileptic Characteristics in Patients with Porencephaly and Schizencephaly". Brain Dev. 34 (7): 546–552. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2011.10.001. PMID 22024697. S2CID 937294.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gould D., Phalan F., Breedveld G., van Mil S., Smith R.; et al. (2005). "Mutations in Col4a 1 Cause Perinatal Cerebral Hemorrhage and Porencephaly". Science. 308 (5725): 1167–1171. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1167G. doi:10.1126/science.1109418. PMID 15905400. S2CID 11439477.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Tonni G., Ferrari B., Defelice C., Centini G. (2005). "Neonatal Porencephaly in Very Low Birth Weight Infants: Ultrasound Timing of Asphyxial Injury and Neurodevelopmental Outcome at Two Years of Age". J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 18 (6): 361–365. doi:10.1080/14767050400029574. PMID 16390800. S2CID 33117246.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Thomas L (2005). "Genetic Mutation Predisposes to Porencephaly". Lancet Neurology. 4 (7): 400. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(05)70114-9. PMID 15991439. S2CID 19804698.

- ↑ Schmidt, M., Klumpp, S., Amort, K., Jawinski, S., & Kramer, M. (2012). Porencephaly in Dogs and Cats: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings and Clinical Signs. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound: The Official Journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association, 53(2), 142-149.

- ↑ Meuwissen M., de Vries L., Verbeek H., Lequin M., Govaert P.; et al. (2011). "Sporadic COL4A1 Mutations with Extensive Prenatal Porencephaly Resembling Hydranencephaly". Neurology. 76 (9): 844–846. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e31820e7751. PMID 21357838. S2CID 207118938.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Breedveld G., de Coo I., Lequin M., Arts W., Heutink P.; et al. (2006). "Novel Mutations in Three Families Confirm a Major Role of COL4A1 in Hereditary Porencephaly". Journal of Medical Genetics. 43 (6): 490–495. doi:10.1136/jmg.2005.035584. PMC 2593028. PMID 16107487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dominguez, R; Aguirre Vila-Coro, A; Slopis, JM; Bohan, TP (June 1991). "Brain and ocular abnormalities in infants with in utero exposure to cocaine and other street drugs". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 145 (6): 688–95. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160060106030. PMID 1709777.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|