Acute proliferative glomerulonephritis

| Acute proliferative glomerulonephritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Proliferative glomerulonephritis[1] | |

| |

| Micrograph of a post-infectious glomerulonephritis. Kidney biopsy. PAS stain. | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

| Symptoms | Edema, proteinuria, haematuria, tiredness and high blood pressure[2] |

| Causes | Caused by Streptococcus bacteria[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Kidney biopsy, Complement profile[3] |

| Treatment | Low-sodium diet, blood pressure management[4] |

| Medication | Diuretics[4] |

| Frequency | 1.5 million (2015)[5] |

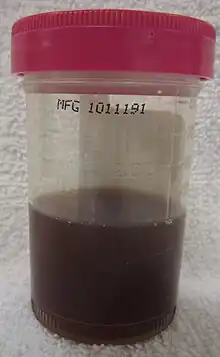

Acute proliferative glomerulonephritis, also known as post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, is a type of kidney disease most frequently associate with a group A strep (GAS) infection.[1] Signs and symptoms vary in severity and include edema, proteinuria, haematuria, tiredness and high blood pressure.[2] Generally there is only a small amount of urine produced and the eyes appear swollen.[2] It is typically noticed as blood in the urine 10 days after a strep infection in children.[6]

Antistreptolysin antibodies may be positive.[4] A confirmed strep infection followed by classic symptoms, a change in streptococcal antibody titre and decreased serum complement may be enough to make the diagnosis.[4] Confirmation may require kidney biopsy.[4][7]

It can be a risk factor for future albuminuria.[8] In adults, the signs and symptoms of infection may still be present at the time when the kidney problems develop, and the terms infection-related glomerulonephritis or bacterial infection-related glomerulonephritis are also used.[9]

Acute glomerulonephritis resulted in 19,000 deaths in 2013, down from 24,000 deaths in 1990 worldwide.[10] In 2015 it affected 1.5 million people.[5] Males are affected twice as frequently as females.[11] It affects around 8.5 to 28.5 per 100,000 people.[11]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms include edema, proteinuria, haematuria, tiredness and high blood pressure.[2] Clinical features vary in severity and there may only be very mild symptoms.[2] Generally there is only a small amount of urine produced and the eyes appear swollen.[2] There may be a fever, headache, anorexia, nausea.[12]

Causes

It is a common complication of bacterial infections, typically skin infection by Streptococcus bacteria types 12, 4 and 1 (impetigo) but also after streptococcal pharyngitis.[13]

Acute proliferative glomerulonephritis (post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis) is caused by an infection with streptococcus bacteria, usually three weeks after infection, usually of the pharynx or the skin, given the time required to raise antibodies and complement proteins.[14][15] The infection causes blood vessels in the kidneys to develop inflammation, this hampers the renal organs ability to filter urine. Acute proliferative glomerulonephritis most commonly occurs in children.[15]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of this disorder is consistent with an immune-complex-mediated mechanism, a type III hypersensitivity reaction. This disorder produces proteins that have different antigenic determinants, which in turn have an affinity for sites in the glomerulus. As soon as binding occurs to the glomerulus, via interaction with properdin, the complement is activated. Complement fixation causes the generation of additional inflammatory mediators.[3]

Complement activation is very important in acute proliferative glomerulonephritis. Apparently immunoglobulin (Ig)-binding proteins bind C4BP. Complement regulatory proteins (FH and FHL-1), may be removed by SpeB, and therefore restrain FH and FHL-1 recruitment in the process of infection.[16]

Diagnosis

The following diagnostic methods can be used for acute proliferative glomerulonephritis:[3]

- Kidney biopsy

- Complement profile

- Imaging studies

- Blood chemistry studies

Clinically, acute proliferative glomerulonephritis is diagnosed following a differential diagnosis between (and, ultimately, diagnosis of) staphylococcal and streptococcal impetigo. Serologically, diagnostic markers can be tested; specifically, the streptozyme test is used and measures multiple streptococcal antibodies: antistreptolysin, antihyaluronidase, antistreptokinase, antinicotinamide-adenine dinucleotidase, and anti-DNAse B antibodies.[3]

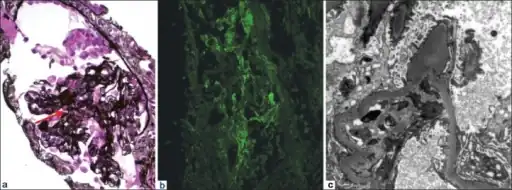

Postinfectious glomerulonephritis- a) Glomerulus with small cellular crescent, fibrinoid necrosis b) IgA predominantly mesangial and segmental capillary wall c) hump-type subepithelial deposits were seen, protruding out basement membrane

Postinfectious glomerulonephritis- a) Glomerulus with small cellular crescent, fibrinoid necrosis b) IgA predominantly mesangial and segmental capillary wall c) hump-type subepithelial deposits were seen, protruding out basement membrane Acute Glomerulonephritis.

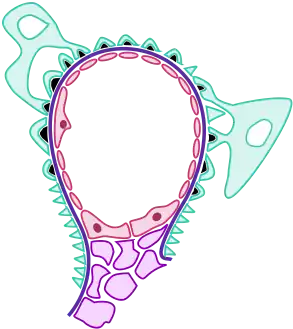

Acute Glomerulonephritis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of acute proliferative glomerulonephritisis is based on the following:

- Causes of acute glomerulonephritis:

- IgA Nephropathy

- Lupus nephritis

- Type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Bacterial endocarditis

- Shunt nephritis

- Cryoglobulinemia

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Causes of generalized edema:

- Malnutrition

- Malabsorption

- Renal affection

- Liver cell failure

- Right side heart failure

- Angioedema

Prevention

It is unclear whether or not acute proliferative glomerulonephritis (i.e., poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis) can be prevented with early prophylactic antibiotic therapy, with some authorities arguing that antibiotics can prevent development of acute proliferative glomerulonephritis.[17]

Treatment

Acute management of acute proliferative glomerulonephritis mainly consists of blood pressure (BP) control. A low-sodium diet may be instituted when hypertension is present. In individuals with oliguric acute kidney injury, the potassium level should be controlled.[3] Thiazide or loop diuretics can be used to simultaneously reduce edema and control hypertension; however electrolytes such as potassium must be monitored. Beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and/or ACE inhibitors may be added if blood pressure is not effectively controlled through diureses alone.[3]

Epidemiology

It affects around 8.5 to 28.5 per 100,000 people.[11] Males are affected twice as frequently as females.[11]

References

- 1 2 "Acute proliferative glomerulonephritis (Concept Id: C0341692) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis: For Clinicians | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 27 June 2022. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Acute Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis Workup at eMedicine

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rhadhakrishnan, Jai M.; Appel, Gerald B. (2020). "113. Glomerular disorders and nephrotic syndromes". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 1 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 759–760. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1. Archived from the original on 2023-01-03. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ Bower, John R. (2022). "33. Pharyngitis". In Jong, Elaine C.; Stevens, Dennis L. (eds.). Netter's Infectious Diseases (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-0-323-71159-3. Archived from the original on 2022-12-28. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- ↑ Sethi, Sanjeev; De Vriese, An S.; Fervenza, Fernando C. (23 April 2022). "Acute glomerulonephritis". Lancet (London, England). 399 (10335): 1646–1663. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00461-5. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 35461559. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ White AV, Hoy WE, McCredie DA (May 2001). "Childhood post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis as a risk factor for chronic renal disease in later life". Med. J. Aust. 174 (10): 492–6. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143394.x. PMID 11419767. S2CID 23172247. Archived from the original on 2012-02-18. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ↑ Nasr SH; Radhakrishnan J; D'Agati VD (May 2013). "Bacterial infection-related glomerulonephritis in adults". Kidney Int. 83 (5): 792–803. doi:10.1038/ki.2012.407. PMID 23302723.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- 1 2 3 4 Rawla, Prashanth; Padala, Sandeep A.; Ludhwani, Dipesh (2022). "Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2022-12-19. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ↑ Garfunkel, Lynn C.; Kaczorowski, Jeffrey; Christy, Cynthia (2007-07-05). Pediatric Clinical Advisor: Instant Diagnosis and Treatment. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 223. ISBN 9780323070584. Archived from the original on 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ↑ Baltimore RS (February 2010). "Re-evaluation of antibiotic treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 22 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833502e7. PMID 19996970. S2CID 13141765.

- ↑ Marianne Gausche-Hill, Susan Fuchs, Loren Yamamoto, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Emergency Physicians. "APLS: The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Resource". Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2004.

- 1 2 "Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (GN): MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Iturbe, B.; Batsford, S. (June 2007). "Pathogenesis of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis a century after Clemens von Pirquet". Kidney International. 71 (11): 1094–1104. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002169. PMID 17342179.

- ↑ Sainato, Rebecca J.; Weisse, Martin E. (January 2019). "Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis and Antibiotics: A Fresh Look at Old Data". Clinical Pediatrics. 58 (1): 10–12. doi:10.1177/0009922818793345. ISSN 0009-9228.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |