Lupus nephritis

| Lupus nephritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: SLE nephritis[1] | |

| |

| Micrograph of diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis showing increased mesangial matrix and mesangial hypercellularity. Kidney biopsy. PAS stain. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, nephrology |

| Symptoms | Foamy urine, swelling of the legs, fever, muscle pains[2] |

| Complications | High blood pressure, kidney failure[2] |

| Usual onset | Young adults[3] |

| Types | Class I to VI[3] |

| Causes | Lupus[2] |

| Risk factors | Genetics[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Suspected based on urine and blood tests, confirmed by a kidney biopsy[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other causes of nephrotic syndrome, kidney stones, acute interstitial nephritis[3] |

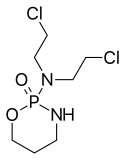

| Treatment | Prednisone, cyclophosphamide, hydroxychloroquine, blood pressure medications, dialysis[2][3] |

| Frequency | Common in lupus[3] |

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a type of kidney disease due to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), an autoimmune disease.[2] Symptoms may include foamy urine, swelling of the legs, fever, and muscle pains.[2] When it occurs, it is generally at least 3 years after the onset of SLE.[3] Complications may include high blood pressure and kidney failure.[2]

Risk factors include certain genetic changes.[3] The underlying mechanism involves a type-III hypersensitivity reaction and the formation of immune complexes.[3] These complexes than build up near the glomerular basement membrane of the kidney and lead to inflammation.[3] Diagnosis may be suspected based on urine and blood tests, and is confirmed by a kidney biopsy.[2]

Treatment depends on the severity of the disease.[3] Medications to suppress the immune system such as prednisone, cyclophosphamide or hydroxychloroquine maybe used.[2] Blood pressure may require management with medications such as ACE inhibitors, diuretics, or beta blockers.[2] Dialysis may eventually bed required.[3]

Up to 50% of adults and 80% of children with lupus are affected.[2] Onset is often in young adults.[3] Males are more commonly affected than females.[2] While lupus was first described in 400 BC by Hippocrates, its effects on the kidneys were first documented in the early 1900s.[3][4]

Signs and symptoms

Cause

The cause of lupus nephritis, a genetic predisposition, plays role in lupus nephritis. Multiple genes, many of which are not yet identified, mediate this genetic predisposition.[7][8]

The immune system protects the human body from infection, and with immune system problems it cannot distinguish between harmful and healthy substances. Lupus nephritis affects approximately 3 out of 10,000 people.[9]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of lupus nephritis has autoimmunity contributing significantly.[10] Autoantibodies direct themselves against nuclear elements. The characteristics of nephritogenic autoantibodies (lupus nephritis) are antigen specificity directed at nucleosome, high affinity autoantibodies form intravascular immune complexes, and autoantibodies of certain isotypes activate complement.[7]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of lupus nephritis depends on blood tests, urinalysis, X-rays, ultrasound scans of the kidneys, and a kidney biopsy. On urinalysis, a nephritic picture is found and red blood cell casts, red blood cells and proteinuria is found. The World Health Organization has divided lupus nephritis into five stages based on the biopsy. This classification was defined in 1982 and revised in 1995.[11][12]

- Class I is minimal mesangial glomerulonephritis which is histologically normal on light microscopy but with mesangial deposits on electron microscopy. It constitutes about 5% of cases of lupus nephritis.[13] Kidney failure is very rare in this form.[13]

- Class II is based on a finding of mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis. This form typically responds completely to treatment with corticosteroids. It constitutes about 20% of cases.[13] Kidney failure is rare in this form.[13]

- Class III is focal proliferative nephritis and often successfully responds to treatment with high doses of corticosteroids. It constitutes about 25% of cases.[13] Kidney failure is uncommon in this form.[13]

- Class IV is diffuse proliferative nephritis. This form is mainly treated with corticosteroids and immunosuppressant drugs. It constitutes about 40% of cases.[13] Kidney failure is common in this form.[13]

- Class V is membranous nephritis and is characterized by extreme edema and protein loss. It constitutes about 10% of cases.[13] Kidney failure is uncommon in this form.[13]

Classification

Class I disease (minimal mesangial glomerulonephritis) in its histology has a normal appearance under a light microscope, but mesangial deposits are visible under an electron microscope. At this stage urinalysis is normal.[14]

Class II disease (mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis) is noted by mesangial hypercellularity and matrix expansion. Microscopic haematuria with or without proteinuria may be seen. Hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, and acute kidney injury are very rare at this stage.[14]

Class III disease (focal glomerulonephritis) is indicated by sclerotic lesions involving less than 50% of the glomeruli, which can be segmental or global, and active or chronic, with endocapillary or extracapillary proliferative lesions. Under the electron microscopy, subendothelial deposits are noted, and some mesangial changes may be present. Immunofluorescence reveals positively for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C1q. Clinically, haematuria and proteinuria are present, with or without nephrotic syndrome, hypertension, and elevated serum creatinine.[14]

Class IV disease (diffuse proliferative nephritis) is both the most severe, and the most common subtype. More than 50% of glomeruli are involved. Lesions can be segmental or global, and active or chronic, with endocapillary or extracapillary proliferative lesions. Under electron microscopy, subendothelial deposits are noted, and some mesangial changes may be present. Clinically, haematuria and proteinuria are present, frequently with nephrotic syndrome, hypertension, hypocomplementemia, elevated anti-dsDNA titres and elevated serum creatinine.[14]

Class V disease (membranous glomerulonephritis) is characterized by diffuse thickening of the glomerular capillary wall (segmentally or globally), with diffuse membrane thickening, and subepithelial deposits seen under the electron microscope. Clinically, stage V presents with signs of nephrotic syndrome. Microscopic haematuria and hypertension may also be seen. Stage V can also lead to thrombotic complications such as renal vein thromboses or pulmonary emboli.[14]

Class VI, or advanced sclerosing lupus nephritis,[7] a final class which is included by most practitioners. It is represented by global sclerosis involving more than 90% of glomeruli, and represents healing of prior inflammatory injury. Active glomerulonephritis is not usually present. This stage is characterised by slowly progressive kidney dysfunction, with relatively bland urine sediment. Response to immunotherapy is usually poor. A tubuloreticular inclusion within capillary endothelial cells is also characteristic of lupus nephritis and can be seen under an electron microscope in all stages. It is not diagnostic however, as it exists in other conditions such as HIV infection.[15] It is thought to be due to the chronic interferon exposure.[16]

Treatment

Drug regimens prescribed for lupus nephritis include mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), intravenous cyclophosphamide with corticosteroids, and the immune suppressant azathioprine with corticosteroids. MMF and cyclophosphamide with corticosteroids are equally effective in achieving remission of the disease, however the results of a recent systematic review found that immunosuppressive drugs were better than corticosteroids for renal outcomes.[17] MMF is safer than cyclophosphamide with corticosteroids, with less chance of causing ovarian failure, immune problems or hair loss. It also works better than azathioprine with corticosteroids for maintenance therapy.[18][19] A 2016 network meta-analysis, which included 32 RCTs of lupus nephritis, demonstrated that tacrolimus and MMF followed by azathioprine maintenance were associated with a lower risk of serious infection when compared to other immunosuppressants or glucocorticoids.[20][21] Individuals with lupus nephritis have a high risk for B-cell lymphoma (which begins in the immune system cells).[5]

References

- ↑ Ponticelli, C.; Moroni, G. (2005-01-01). "Renal transplantation in lupus nephritis". Lupus. 14 (1): 95–98. doi:10.1191/0961203305lu2067oa. ISSN 0961-2033. PMID 15732296.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Lupus and Kidney Disease (Lupus Nephritis) | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Musa, R; Brent, LH; Qurie, A (January 2020). "Lupus Nephritis". PMID 29762992.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Rose, Noel R.; Mackay, Ian R. (2006). The Autoimmune Diseases. Elsevier. p. 826. ISBN 978-0-08-045474-0. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-23.

- 1 2 "Lupus Nephritis". www.niddk.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-01-04. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Lupus Nephritis - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 "Lupus Nephritis: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". 2018-12-23. Archived from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Salgado, Alberto (2012). "Lupus Nephritis: An Overview of Recent Findings". Autoimmune Diseases. 2012: 849684. doi:10.1155/2012/849684. PMC 3318208. PMID 22536486.

- ↑ "Lupus nephritis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Rhadhakrishnan, Jai M.; Appel, Gerald B. (2020). "113. Glomerular disorders and nephrotic syndromes". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 1 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1. Archived from the original on 2023-01-03. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ↑ Weening JJ, D'Agati VD, Schwartz MM, et al. (February 2004). "The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15 (2): 241–50. doi:10.1097/01.ASN.0000108969.21691.5D. PMID 14747370. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ "National Guideline Clearinghouse | American College of Rheumatology guidelines for screening, treatment, and management of lupus nephritis". www.guideline.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-09-18. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Table 6-4 in: Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewis, Edmund J.; Schwartz, Melvin M. (2010-11-04). Lupus Nephritis. OUP Oxford. pp. 174–177. ISBN 9780199568055. Archived from the original on 2016-06-23. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ↑ Kfoury H (2014). "Tubulo-reticular inclusions in lupus nephritis: are they relevant?". Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 25 (3): 539–43. doi:10.4103/1319-2442.132169. PMID 24821149.

- ↑ Karageorgas TP, Tseronis DD, Mavragani CP (2011). "Activation of type I interferon pathway in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with distinct clinical phenotypes". Journal of Biomedicine & Biotechnology. 2011: 1–13. doi:10.1155/2011/273907. PMC 3227532. PMID 22162633.

- ↑ Singh, Jasvinder A.; Hossain, Alomgir; Kotb, Ahmed; Oliveira, Ana; Mudano, Amy S.; Grossman, Jennifer; Winthrop, Kevin; Wells, George A. (2016). "Treatments for Lupus Nephritis: A Systematic Review and Network Metaanalysis". The Journal of Rheumatology. 43 (10): 1801–1815. doi:10.3899/jrheum.160041. ISSN 0315-162X. PMID 27585688.

- ↑ Henderson, L.; Masson, P.; Craig, JC.; Flanc, RS.; Roberts, MA.; Strippoli, GF.; Webster, AC. (2012). "Treatment for lupus nephritis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD002922. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002922.pub3. PMID 23235592.

- ↑ Masson, Philip (2011). "Induction and maintenance treatment of proliferative lupus nephritis" (PDF). Nephrology. 18: 71–72. doi:10.1111/nep.12011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Singh, Jasvinder A.; Hossain, Alomgir; Kotb, Ahmed; Wells, George (2016-09-13). "Risk of serious infections with immunosuppressive drugs and glucocorticoids for lupus nephritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". BMC Medicine. 14 (1): 137. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0673-8. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 5022202. PMID 27623861.

- ↑ Tang, Kuo-Tung; Tseng, Chien-Hua; Hsieh, Tsu-Yi; Chen, Der-Yuan (June 2018). "Induction therapy for membranous lupus nephritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 21 (6): 1163–1172. doi:10.1111/1756-185X.13321. ISSN 1756-185X. PMID 29879319.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |