Premunition

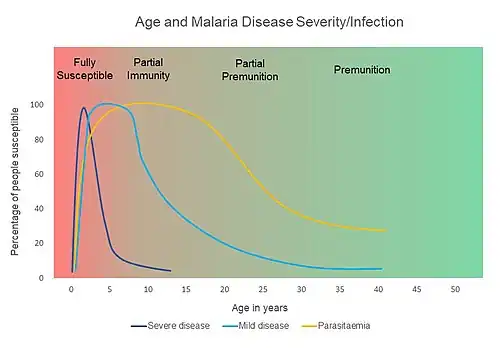

Premunition, also known as infection-immunity, is a host response that protects against high numbers of parasite and illness without eliminating the infection.[1] This type of immunity is relatively rapid, progressively acquired, short-lived, and partially effective.[2] For malaria, premunition is maintained by repeated antigen exposure from infective bites.[2] Thus, if an individual departs from an endemic area, he or she may lose premunition and become susceptible to malaria.[2]

Antibody action contributes to premunition.[3] However, premunition is probably much more complex than simple antibody and antigen interaction.[2] In the case of malaria, the sporozoite and merozoite stages of Plasmodium elicit the antibody response which leads to premunition.[3] Immunoglobulin E targets the parasites and leads to eosinophil degranulation which releases major basic protein that damages the parasites, and other factors elicit a local inflammatory response.[3] However, Plasmodium can change its surface antigens, so the development of an antibody repertoire that can recognize multiple surface antigens is important for premunition to be achieved.[4]

Premunition has not been well-studied, and although it likely occurs broadly, it is mainly emphasized for its role in malaria, tuberculosis, syphilis and relapsing fever.[5]

Premunization is the artificial induction of premunition.[6]

Premunity is progressive development of immunity in individuals exposed to an infective agent,[7] mainly belonging to protozoa and Rickettsia, but not in viruses.[8] After the initial infection, which generally occurs in childhood, the effect in subsequent infections is diminished. Infections thereafter may exhibit little or no symptomatology in spite of parasitemia. The next stage is resistance to infection altogether.

Loss of premunity is estimated to be the cause of the rebound of malaria[9] in 1965 in India after the dramatic success of the National Malaria Control Programme that was launched for rural India in 1953.

Premunity occurs in infections of babesiosis,[10][11] malaria[7][12] Onchocerca volvulus,[13] and Trichomonas.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Ryan, Kenneth J.; Ray, C. George, eds. (2010). Sherris Medical Microbiology (5 ed.). ISBN 978-0-07-160402-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Jean Mouchet; Pierre Carnevale; Sylvie Manguin (2008). Biodiversity of Malaria in the World. John Libbey Eurotext. p. 41. ISBN 978-2-7420-0616-8. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 Nandini Shetty; Julian W. Tang; Julie Andrews (19 May 2009). Infectious Disease: Pathogenesis, Prevention and Case Studies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4051-3543-6. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ↑ Mandell, Gerald L.; Bennett, John E. (John Eugene); Dolin, Raphael. (2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious disease. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 3444. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

- ↑ Kothari, M. L.; Lopa a, M. (1976). "The nature of immunity". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 22 (2): 50–58. PMID 1032677.

- ↑ H. (CON) Aspock (3 January 2008). Encyclopedia of Parasitology. Springer. p. 150. ISBN 978-3-540-48994-8. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Effects of impregnated bednets". Modelling group at the Department of Medical Biometry, University of Tübingen. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ↑ Seifert, Horst S. H. (1 January 1996). Tropical Animal Health. Springer. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7923-3821-5.

- ↑ "Reports of Expert Committees to the Interim Commission" (PDF). Official Records of the World Health Organisation No.8. April 1948.

- ↑ Shaw, Susan E.; Day, Michael J. (11 April 2005). Arthropod-borne Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Manson Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-84076-578-6.

- ↑ Hoyte, HMD (November 1961). "Initial Development of Infections with Babesia bigeminal*". The Journal of Protozoology. 8 (4): 462–466. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1961.tb01242.x.

- ↑ Maegraith, B. G. (1 January 1973). Malaria. Tropical Pathology. Spezielle pathologische Anatomie. Vol. 8. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 319–349. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-00226-1_11. ISBN 978-3-662-00226-1.

- ↑ Duke, BO (1968). "Reinfections with Onchocerca volvulus in cured patients exposed to continuing transmission". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 39 (2): 307–9. PMC 2554563. PMID 5303412.

- ↑ blaz (5 October 2009). "DETAILED THREAD ON CANKER TRICHOMONIASIS". pigeonbasics.com. copied from and citing Peters, Wim (1995). Fit to win : health, diagnosis and treatment in racing pigeons. Londin [sic]: Racing Pigeon. ISBN 978-0-85390-043-6.

Further reading

- Mayr, A (Feb 24, 1978). "[Premunity, premunization and paraspecific effect of immunizations (author's transl)]". MMW, Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 120 (8): 239–46. PMID 305537.

- Peters, W (November 1960). "Part VI. Unstable highland malaria—analysis of data and possibilities for eradication of malaria". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 54 (6): 542–48. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(60)90029-8.

- Saracino, Annalisa; Nacarapa, Edy A; da Costa Massinga, Ézio A; Martinelli, Domenico; Scacchetti, Marco; de Oliveira, Carlos; Antonich, Anita; Galloni, Donata; Ferro, Josefo J; Macome, César A (2012). "Prevalence and clinical features of HIV and malaria co-infection in hospitalized adults in Beira, Mozambique". Malaria Journal. 11 (1): 241. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-241. PMC 3439710. PMID 22835018.

- Fiennes, RN (Jun 14, 1947). "Immunity and premunity in cattle trypanosomiasis". The Veterinary Record. 59 (22): 291–92. PMID 20251204. and PMID 20251205