Prussian blue (medical use)

Prussian blue | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Radiogardase, others |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Thallium poisoning, radioactive cesium poisoning[1] |

| Side effects | Constipation, low blood potassium, dark stools[1][2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | by mouth |

| Defined daily dose | Not established[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Molar mass | 859.24 |

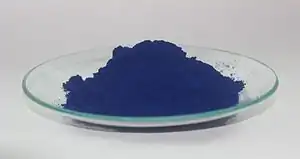

Prussian blue, also known as potassium ferric hexacyanoferrate, is used as a medication to treat thallium poisoning or radioactive cesium poisoning.[1][4] For thallium it may be used in addition to gastric lavage, activated charcoal, forced diuresis, and hemodialysis.[2][5] It is given by mouth or nasogastric tube.[4][5] Prussian blue is also used in the urine to test for G6PD deficiency.[6]

Side effects may include constipation, low blood potassium, and stools that are dark.[1][2] With long-term use, sweat may turn blue.[2] It works by binding to and thus preventing the absorption of thallium and cesium from the intestines.[2]

Prussian blue was developed around 1706.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] As of 2016, it is only approved for medical use in Germany, the United States, and Japan.[9][10][11] In the United States a course of treatment costs more than $200.[4] Access to medical-grade Prussian blue can be difficult in many areas of the world including the developed world.[12]

Medical uses

Prussian blue is used to treat thallium poisoning or radioactive cesium poisoning.[1][4][13] It may also be used for exposure to radioactive material until the underlying type is determined.[2]

Often it is given with mannitol or sorbitol to increase the speed it moves through the intestines.[5]

Prussian blue is also used to detect hemosiderin in urine to confirm a diagnosis of G6PD deficiency.[6]

Thallium poisoning

For thallium it may be used in addition to gastric lavage, forced diuresis, and hemodialysis.[2]

It is given until the amount of thallium in the urine drops to below 0.5 mg per day.[5]

Caesium poisoning

It is specifically only used for radioactive caesium poisoning when the caesium has entered the body either by swallowing or breathing it in.[5]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 65. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Prussian Blue". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 472. ISBN 9781284057560.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dart, Richard C. (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 248,279. ISBN 9780781728454. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.

- 1 2 "Glucose-6-phosphate dehyrogenase deficiency — Medlibes: Online Medical Library". medlibes.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-15. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ↑ Hall, Alan H.; Isom, Gary E.; Rockwood, Gary A. (2015). Toxicology of Cyanides and Cyanogens: Experimental, Applied and Clinical Aspects. John Wiley & Sons. p. 43. ISBN 9781118628942. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Goyer, Robert A. (2016). Metal Toxicology: Approaches and Methods. Elsevier. p. 93. ISBN 9781483288567. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ↑ Dobbs, Michael R. (2009). Clinical Neurotoxicology: Syndromes, Substances, Environments. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 280. ISBN 0323052606. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ↑ "Radioaktivität: Berliner Blau als Arzneimittel". Dtsch Arztebl (in Deutsch). 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ↑ Archiver, Truthout (27 June 2011). "Fukushima's Cesium Spew - Deadly Catch-22s in Japan Disaster Relief". Truthout. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers on Calcium-DTPA and Zinc-DTPA (Updated)". U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|