Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect

| Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect | |

|---|---|

| Other names | PA-VSDS (abbr.)[1] |

| |

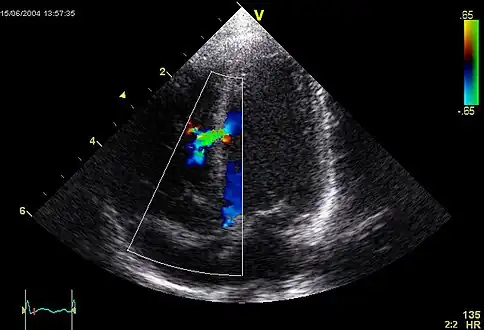

| A ventricular septal defect, one of the symptoms of this condition, under an ultrasound. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

| Risk factors | Genetic and environmental factors usually come into place |

| Diagnostic method | Radiological studies such as chest CT scans. |

| Differential diagnosis | Pulmonary atresia |

| Prognosis | poor without treatment |

| Frequency | rare |

| Deaths | untreated PAVSD patients more likely to suffer from a premature death |

Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect is a rare birth defect characterized by pulmonary valve atresia occurring alongside a defect on the right ventricular outflow tract.[2][3][4][5]

It is a type of congenital heart disease/defect,[6] and one of the two recognized subtypes of pulmonary atresia, the other being pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum.[7][8]

Signs and symptoms

The condition consists of atresia affecting the pulmonary valve and a hypoplastic right ventricular outflow tract. The ventricular septal defect doesn't impede the in and outflowing of blood in the ventricular septum, which helps it form during fetal life.[3][5]

The spectrum of symptoms exhibited by children with this condition depends on the severity of the condition, while some barely show symptoms, others might develop complications such as congestive heart failure.[9][10][11]

In symptomatic children, symptoms become apparent soon after birth, these usually consist of the following:[3][5][10][12][13][14][15]

- Cyanosis

- Breathing difficulties

- Feeding difficulties

- Exhaustion while being fed

- Heart murmur

- Excessive daytime sleepiness

- Sticky skin

Other features can occur alongside this birth defect, including other congenital anomalies such as polydactyly, microcephaly, congenital hearing loss (sensorineural type), renal agenesis, dextrocardia, etc.[16][17]

The condition has been called a severe form of Tetralogy of Fallot.[18][19][9][20][21][12][11]

If deformed blood vessels coming from the thoracic aorta appear alongside this condition, the phenotype is renamed to pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect and major aortopulmonary collaterals.[22]

Complications

Children with this condition are at a higher risk of developing the following complications:[11][23]

- Failure to thrive

- Recurrent chest infections

- Endocarditis

- Epilepsy

- Stroke

- Arrhythmia

- Heart failure

- Premature death

Children whose PAVSD is caused by DiGeorge syndrome (also known as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome) are more likely to suffer from the post-surgical complications (especially respiratory ones) associated with surgeries that treat this defect.[24]

Women with PAVSD are at a slightly higher risk of being infertile and having miscarriages or children with a congenital heart defect.[25]

Airway hyperresponsiveness is a commonly seen co-morbidity among those afflicted with PAVSD.[26]

Pathogenesis

Pulmonary atresia in PAVSD takes place during the first 8 weeks of fetal life, when the pulmonary valve that is supposed to form, fails to form, this doesn't allow blood to flow through the pulmonary artery from the right ventricle. The ventricular septal defect associated with PAVSD lets the right ventricule form.[27][28][29][30]

In some cases of PAVSD, major aortopulmonary collateral arteries develop; in a normal fetus, these arteries usually develop but then start deteriorating after pulmonary arteries grow, in fetuses with PAVSD, the pulmonary arteries don't develop, and this gives a chance to the major aortopulmonary collateral arteries to develop fully.[31]

Pathophysiology

The mildest variant of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect involves pulmonary atresia with normally developed main pulmonary artery and branch pulmonary arteries, the blood that flows to the lungs from the right side of the heart goes to the left side of the heart through the ventricular septum which then flows through the patent ductus arteriosus. The most severe variant involves the presence of severely hypoplastic main pulmonary arteries and branch pulmonary arteries, alongside agenesis of the patent ductus arteriosus. Blood flow to the lungs comes from various dysplastic (malformed) blood vessels from the thoracic aorta called major aortapulmonary collateral arteries, these blood vessels narrow down as time goes on.[32][33][34]

Causes

Although this birth defect is congenital, the exact cause is unknown, and it may vary between children with the condition, the following factors have been known to influence the risk of a baby being born with the condition:[35][36]

Genetics

The molecular genetics of this condition isn't known in most people with PA(VSD), however, there have been candidate genes found to be possibly implicated in the pathogenesis of this condition:[37][38]

- DNAH10

- DST

- FAT1

- HMCN1

- HNRNPC

- TEP1

- TYK2

- NDRG4

- TBX5

- NKX2.5

- GATA4

There have also been copy number variants described in the medical literature as associated with PA(VSD):[39]

- Deletion in chromosome 16p11.2

- Deletion in chromosome 5q35.3

- Deletion in chromosome 5p13.1

- Deletion in chromosome 22q11.2

- Deletion in chromosome 15q11.2

- Deletion in chromosome 8p23.2

- Deletion in chromosome 17p13.2

- Duplication in chromosome 5q14.1

- Duplication in chromosome 10p13

A 1998 study done in Britain revealed that children with a mother who had a congenital heart defect (including PAVSD) had a higher risk of being born with a congenital heart defect themselves than those whose father had a congenital heart defect.[40]

Syndromes

Some cases of PA(VSD) have been associated with genetic syndromes such as VACTERL association, Alagille syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, trisomy 13, 18, and 21.[32][2][41]

Environmental

While congenital heart defects can't be acquired, they can also be caused by environmental factors the mother exposed herself to before and/or during pregnancy, these include:[42]

- Smoking

- Certain medications (e.g. thalidomide, retinoids, or vitamin A coegers)

- Alcohol consumption

- Vehicle exhaust components

- By-products of disinfectants

- Incinerators (proximity)

- Agricultural pesticides

- Solvents

- Landfill sites

- Heavy metals

Maternal exposure to carbon monoxide from smoke (e.g. from cigarettes) has been known for having the ability of quickly crossing the placenta into the fetus, which then attaches itself to fetal haemoglobin, leaving a shortage of nutrients and oxygen as a result. A relation between these events and congenital heart disease (including PAVSD) has been showed in 3 recent meta-analyses.[42]

Paternal smoking (that is, smoking by the father) has also been shown to be a contributing factor to congenital heart disease; while light smoking slightly increased the risk of the man's offspring having a (congenital) conotruncal heart defect, heavy smoking of more than 14 cigarettes a day doubled the risk for said man to have a child with congenital heart disease. Higher amounts than this were linked to a higher risk of having children with septal defects and/or obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract.[42]

Other risk factors include maternal obesity, diabetes, rubella, indomethacin tocolysis, phenylketonuria, or elderly age.[43][9]

Multifactorial: involving genetic and environmental factors at the same time

A link between certain genes and maternal smoking has been shown to increase the chance of having children with congenital heart disease (including PAVSD): mothers who have a CC genotype at position 677 of the MTHFR gene have an increased chance of having a CHD-ridden child. Other genes that increase the chance of a child with CHD in smoker mothers who carry genetic variations in them include ERCC1, ERCC5, PARP2, and OSGEP.[42]

Diagnosis

There are various ways of diagnosing this congenital heart defect both prenatally and postnatally, these methods include:[44][45]

- Ultrasound

- Pulse oximetry

- Chest X-ray

- Echocardiogram

- Electrocardiogram

- Cardiac catheterization

- Cardiac CT scan

- Genetic testing (particularly if other systemic birth anomalies are seen alongside the pulmonary atresia and ventricular septal defect).

Management

When the disorder is detected (usually before or soon after birth), prostaglandin will be temporarily used as soon as possible to keep the ductus arteriosus open for as long as possible until surgery can be done, this is done so that blood can keep flowing to the lungs, since the bodies of babies with pulmonary atresia usually use the ductus arteriosus for lung blood flow pre-natally until birth, after which it closes.[46][47][48][49][32][50][51][52]

Afterwards, this anomaly is usually managed with surgeries for improvement of blood flow and function of the heart, although what kind of treatment one gets depends on the structure of the cardiorespiratory system.[44][53][54][55][56]

The surgical methods that can be used to treat (for the long-term) this condition include:[44][57]

- Catheter procedure for pulmonary artery branches

- Systemic-to-pulmonary artery shunt

- Neonatal complete repair

- One-stage complete repair

- Balloon septostomy

- Staged unifocalization

Frequency

Frequency estimates vary between populations, estimates range from 0.01% to 0.2% of live births with PAVSD.[58][32][37] It is believed to make up for 1-2% of cases of congenital heart defects worldwide.[59][32][60]

Of all patients with PAVSD, around 25–32% of them have a microdeletion of the 22q11.2 chromosome.[61]

Prognosis

Without treatment, it is a highly life-threatening condition, so prognosis is poor.[35][34] If surgery isn't performed in severe cases, the child can (and will) die, since the phenotype of pulmonary atresia is not compatible with life due to the pulmonary valve atresia resulting in reduced blood oxygenation.[9][62][63]

Life expectancy for untreated children with PAVSD is 10 years.[10] Survival rates for untreated people with this defect have been reported to be 50% at the tenth decade and 10% at the twentieth decade,[56] and out of these untreated patients, those who do not have major aortopulmonary arteries have a higher chance of living to their 30s than those who do have them, as the latter have a 40% chance of surviving to the tenth decade and a 20% chance of doing so to the thirtieth decade.[64]

Prognosis after surgical intervention is generally good.[65]

History

This combination of birth defects was first described in 1980 by DiChiara et al., their patients were a father and his son from the United States both of which had pulmonary atresia and a ventricular septal defect. Up until that point, there had been no familial cases of PA with a VSD. A multifactorial etiology (that is, a cause involving genetics and the environment) was suspected in these patients and they were offered medical counseling for the condition.[66]

As of 2011, the oldest patient with untreated PAVSD was a 59-year-old woman from Japan. Her condition was discovered in childhood but she refused to get any surgery to treat it (including cardiac catheterization), she developed dyspnea during her teenage years. Radiological studies showed a ventricular septal defect alongside cardiac and arterial anomalies (heart silhouette enlargement, elevation of the cardiac apex, presence of a right aortic arch, enlargement affecting the main pulmonary arteries and their major branches, high pulmonary artery vascularity, and ventricular septal defect).[67]

See also

References

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia". Program Operations Manual System (POMS). U.S. Social Security Administration.

- 1 2 "Pulmonary Atresia: Symptoms, Causes and Treatment". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- 1 2 3 "Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect – About the Disease – Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Clinical Synopsis – 178370 – PULMONARY ATRESIA WITH VENTRICULAR SEPTAL DEFECT – OMIM". omim.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- 1 2 3 "Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect". Orphanet. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia". GOSH Hospital site. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum (IVS)". Pavilion for Women. Texas Children's Hospital. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Axelrod DM, Roth SJ. "Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA/IVS)". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- 1 2 3 4 Sana MK, Ahmed Z (2022). "Pulmonary Atresia With Ventricular Septal Defect". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32965948. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- 1 2 3 Merrow Jr AC, Hariharan S, eds. (2017). "Pulmonary Atresia". Imaging in Pediatrics. Salt Lake City: Elsevier. p. 91. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-47778-9.50069-6. ISBN 978-0-323-47778-9.

Life expectancy when untreated < 10 years

- 1 2 3 Rodriguez-Cruz E, Aggarwal S, Delius RE, Sallaam S, Odim J (2022-01-10). Windle ML, Mancini MC, Berger S (eds.). "Pulmonary Atresia With Ventricular Septal Defect: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". Medscape.

- 1 2 "Pulmonary atresia". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Atresia". Norton Children's. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Atresia". The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research(MFMER). St. Elizabeth Healthcare. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ↑ Lertsakulpiriya K, Vijarnsorn C, Chanthong P, Chungsomprasong P, Kanjanauthai S, Durongpisitkul K, et al. (March 2020). "Current era outcomes of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect: A single center cohort in Thailand". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 5165. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.5165L. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61879-2. PMC 7083910. PMID 32198468.

- ↑ Liang L, Wang Y, Zhang Y (2022). "Prenatal Diagnosis of Pulmonary Atresia With Ventricular Septal Defect and an Aberrant Ductus Arteriosus in a Dextrocardia by Two- and Three-Dimensional Echocardiography: A Case Report". Frontiers in Medicine. 9: 904662. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.904662. PMC 9283767. PMID 35847823.

- ↑ "Cardiology: Pulmonary Atresia with VSD". www.rch.org.au. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Bravo-Jaimes K, Walton B, Tung P, Smalling RW (2020). "An Unusual Cause of Hypoxia: Ventricular Septal Defect, Pulmonary Artery Atresia, and Major Aortopulmonary Collaterals Diagnosed in the Adult Cardiac Catheterization Lab". Case Reports in Cardiology. 2020: 4726529. doi:10.1155/2020/4726529. PMC 7007747. PMID 32047673.

- ↑ CDC (2019-11-18). "Congenital Heart Defects – Facts about Pulmonary Atresia". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Atresia". Boston Children's Hospital. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Reddy VM, McElhinney DB, Amin Z, Moore P, Parry AJ, Teitel DF, Hanley FL (April 2000). "Early and intermediate outcomes after repair of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries: experience with 85 patients". Circulation. 101 (15): 1826–1832. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.101.15.1826. PMID 10769284.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Ackerman MJ, Wylam ME, Feldt RH, Porter CJ, Dewald G, Scanlon PD, Driscoll DJ (July 2001). "Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect and persistent airway hyperresponsiveness". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 122 (1): 169–177. doi:10.1067/mtc.2001.114942. PMID 11436051.

- ↑ Drenthen W, Pieper PG, Zoon N, Roos-Hesselink JW, Voors AA, Mulder BJ, et al. (July 2006). "Pregnancy after biventricular repair for pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect". The American Journal of Cardiology. 98 (2): 262–266. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.094. PMID 16828605.

- ↑ Bode-Thomas, F.; Hyacinth, IH.; Yilgwan, CS. (2010-04-14). "Co-existence of Ventricular Septal Defect and Bronchial Asthma in Two Nigerian Children". Clinical Medicine Insights: Case Reports. 3: 5–8. doi:10.4137/ccrep.s4584. ISSN 1179-5476. PMC 2908369. PMID 20657755.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia | Children's Wisconsin". childrenswi.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Atresia With Ventricular Septal Defect treatment at the…". Partners in Care. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Congenital Pulmonary Atresia | Symptoms, Treatment & Repair". www.cincinnatichildrens.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "default – Stanford Medicine Children's Health". www.stanfordchildrens.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Boshoff D, Gewillig M (June 2006). "A review of the options for treatment of major aortopulmonary collateral arteries in the setting of tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia". Cardiology in the Young. 16 (3): 212–220. doi:10.1017/S1047951106000606. PMID 16725060. S2CID 30970579.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Pulmonary Atresia". CS Mott Children's Hospital. Michigan Medicine. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Liu J, Li H, Liu Z, Wu Q, Xu Y (2016-01-07). "Complete Preoperative Evaluation of Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect with Multi-Detector Computed Tomography". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0146380. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1146380L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146380. PMC 4712153. PMID 26741649.

- 1 2 "Diseases And Conditions". St. Clair Health. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- 1 2 Gao M, He X, Zheng J (March 2017). "Advances in molecular genetics for pulmonary atresia". Cardiology in the Young. 27 (2): 207–216. doi:10.1017/S1047951116001487. PMID 27655138. S2CID 24050754.

- ↑ Wang X, Li P, Chen S, Xi L, Guo Y, Guo A, Sun K (February 2014). "Influence of genes and the environment in familial congenital heart defects". Molecular Medicine Reports. 9 (2): 695–700. doi:10.3892/mmr.2013.1847. PMID 24337398.

- 1 2 Peng J, Wang Q, Meng Z, Wang J, Zhou Y, Zhou S, et al. (February 2021). "A loss-of-function mutation p.T256M in NDRG4 is implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect (PA/VSD) and tetralogy of Fallot (TOF)". FEBS Open Bio. 11 (2): 375–385. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.13044. PMC 7876499. PMID 33211401.

- ↑ Shi X, Zhang L, Bai K, Xie H, Shi T, Zhang R, et al. (2020-01-01). "Identification of rare variants in novel candidate genes in pulmonary atresia patients by next generation sequencing". Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 18: 381–392. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2020.01.011. PMC 7044470. PMID 32128068.

- ↑ Xie H, Hong N, Zhang E, Li F, Sun K, Yu Y (2019). "Identification of Rare Copy Number Variants Associated With Pulmonary Atresia With Ventricular Septal Defect". Frontiers in Genetics. 10: 15. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00015. PMC 6360179. PMID 30745907.

- ↑ Burn J, Brennan P, Little J, Holloway S, Coffey R, Somerville J, et al. (January 1998). "Recurrence risks in offspring of adults with major heart defects: results from first cohort of British collaborative study". Lancet. 351 (9099): 311–316. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06486-6. PMID 9652610. S2CID 40685852.

- ↑ Wiezell E, F Gudnason J, Synnergren M, Sunnegårdh J (May 2021). "Outcome after surgery for pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, a long-term follow-up study". Acta Paediatrica. 110 (5): 1610–1619. doi:10.1111/apa.15732. PMC 8248001. PMID 33351279.

- 1 2 3 4 Nicoll R (September 2018). "Environmental Contaminants and Congenital Heart Defects: A Re-Evaluation of the Evidence". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (10): 2096. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102096. PMC 6210579. PMID 30257432.

- ↑ Jenkins KJ, Correa A, Feinstein JA, Botto L, Britt AE, Daniels SR, et al. (June 2007). "Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics". Circulation. 115 (23): 2995–3014. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183216. PMID 17519397. S2CID 8481352.

- 1 2 3 "Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect – Overview – Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Gindes L, Salem Y, Gasnier R, Raucher A, Tamir A, Assa S, et al. (February 2021). "Prenatal diagnosis of major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCA) in fetuses with pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect and agenesis of ductus arteriosus". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 35 (25): 5400–5408. doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.1881475. PMID 33525939. S2CID 231754846.

- ↑ "Single Ventricle Defects". www.heart.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Atresia (PA)". Children's Health Orange County. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia". Middlesex Health. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)". www.childrensmercy.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia Information | Mount Sinai – New York". Mount Sinai Health System. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ The Medindia Medical Review Team (9 April 2009). "Pulmonary Atresia – Types, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Management". Medindia. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Shah AA, Rhodes JF, Jaquiss RD (2014). "Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect". In Da Cruz EM, Ivy D, Jaggers J (eds.). Pediatric and Congenital Cardiology, Cardiac Surgery and Intensive Care. London: Springer. pp. 1527–1542. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-4619-3_19. ISBN 978-1-4471-4619-3.

- ↑ "Surgery for Pulmonary Atresia with VSD for Children". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Understanding your child's heart – Pulmonary atresia with a ventricular septal defect". British Heart Foundation.

- 1 2 Haydin S, Genç SB, Ozturk E, Yıldız O, Gunes M, Tanidir IC, Guzeltas A (August 2020). "Surgical Strategies and Results for Repair of Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collaterals: Experience of a Single Tertiary Center". Brazilian Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery. 35 (4): 445–451. doi:10.21470/1678-9741-2019-0055. PMC 7454616. PMID 32864922.

- ↑ Zou MH, Ma L, Cui YQ, Wang HZ, Li WL, Li J, Chen XX (2021). "Outcomes After Repair of Pulmonary Atresia With Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries: A Tailored Approach in a Developing Setting". Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 8: 665038. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.665038. PMC 8079636. PMID 33937364.

- ↑ ISUOG. "Pulmonary artesia with ventricular septal defect". www.isuog.org. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect". Vall d'Hebron University Hospital. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect: What you should know". www.healio.com. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Hofbeck M, Rauch A, Leipold G, Singer H (March 1998). "Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary atresia and ventricular septal defect". Progress in Pediatric Cardiology. 9 (2): 113–118. doi:10.1016/S1058-9813(98)00052-6. ISSN 1058-9813.

- ↑ "Conditions". Leeds Congenital Hearts. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ Fan C, Yang Y, Xiong L, Yin N, Wu Q, Tang M, Yang J (February 2017). "Reconstruction of the pulmonary posterior wall using in situ autologous tissue for the treatment of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect". Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 12 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s13019-017-0578-4. PMC 5324245. PMID 28231853.

- ↑ Kaskinen AK, Happonen JM, Mattila IP, Pitkänen OM (May 2016). "Long-term outcome after treatment of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect: nationwide study of 109 patients born in 1970–2007". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 49 (5): 1411–8. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezv404. PMID 26620210.

- ↑ Kirklin JW, Blackstone EH, Shimazaki Y, Maehara T, Pacifico AD, Kirklin JK, Bargeron LM (July 1988). "Survival, functional status, and reoperations after repair of tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 96 (1): 102–116. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(19)35303-6. PMID 3386286.

- ↑ DiChiara JA, Pieroni DR, Gingell RL, Bannerman RM, Vlad P (May 1980). "Familial pulmonary atresia. Its occurrence with a ventricular septal defect". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 134 (5): 506–508. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130170056019. PMID 7377161.

- ↑ Fukui D, Kai H, Takeuchi T, Gondo T, Oba T, Mawatari K, et al. (November 2011). "Longest survivor of pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect: well-developed major aortopulmonary collateral arteries demonstrated by multidetector computed tomography". Circulation. 124 (19): 2155–2157. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.035469. PMID 22064959. S2CID 207657689.