Rectus sheath

| Rectus sheath | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vagina musculi recti abdominis |

| TA98 | A04.5.01.003 |

| TA2 | 2359 |

| FMA | 9587 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

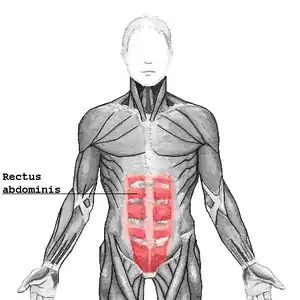

The rectus sheath, also called the rectus fascia,[1] is formed by the aponeuroses of the transverse abdominal and the internal and external oblique muscles. It contains the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles.

Structure

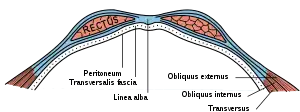

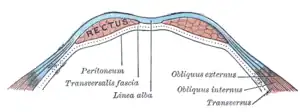

The rectus sheath can be divided into anterior and posterior laminae. The arrangement of the layers has important variations at different locations in the body.

Below the costal margin

For context, above the sheath are the following two layers:

- Camper's fascia (anterior part of Superficial fascia)

- Scarpa's fascia (posterior part of the Superficial fascia)

Within the sheath, the layers vary:

| Region | Illustration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Above the arcuate line |  | At the lateral margin of the rectus, the aponeurosis of the internal oblique divides into two lamellae:

|

| Below the arcuate line |  | Below this level, the aponeuroses of all three muscles (including the transversus) pass in front of the rectus. |

Below the sheath are the following three layers:

The rectus, in the situation where its sheath is deficient below, is separated from the peritoneum only by the transversalis fascia, in contrast to the upper layers, where part of the internal oblique also runs beneath the rectus. Because of the thinner layers below, this region is more susceptible to herniation.

Above the costal margin

Since the tendons of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis only reach as high as the costal margin, it follows that above this level the sheath of the rectus is deficient behind, the muscle resting directly on the cartilages of the ribs, and being covered only by the tendons of the external obliques.

Clinical significance

The rectus sheath is a useful attachment for surgical meshes during abdominal surgery.[2] This has a higher risk of infection than many other attachment sites.[2]

Additional images

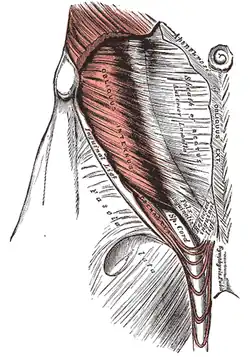

The Cremaster

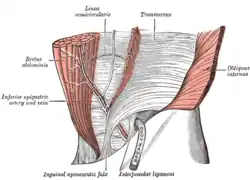

The Cremaster The interfoveolar ligament, seen from in front.

The interfoveolar ligament, seen from in front.

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 416 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 416 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Te Linde, Richard W. (1977), Rock, John A.; Jones Howard W. (eds.), Te Linde's Operative Gynecology (PDF) (10th ed.), Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott (published 2003), p. 107, retrieved 2018-10-01.

- 1 2 Hollinsky, C. (2011-01-01), Ducheyne, Paul (ed.), "6.638 - Biomaterials for Hernia Repair", Comprehensive Biomaterials, Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 593–604, ISBN 978-0-08-055294-1, retrieved 2021-01-21

External links

- Anatomy figure: 35:04-02 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Incisions and the contents of the rectus sheath."

- Anatomy photo:35:10-0103 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Anterior Abdominal Wall: The Rectus Abdominis Muscle"

- Anatomy image:7180 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - anterior layer

- Anatomy image:7133 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - posterior layer above arcuate line

- Anatomy image:7574 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - posterior layer above arcuate line

- rectussheath at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- Atlas image: abdo_wall60 at the University of Michigan Health System - "The Rectus Sheath, Anterior View & Transverse Section"