SCARF syndrome

| SCARF syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Skeletal abnormalities, Cutis laxa, craniostenosis, Ambiguous genitalia, Retardation, and Facial abnormalities [1] | |

| |

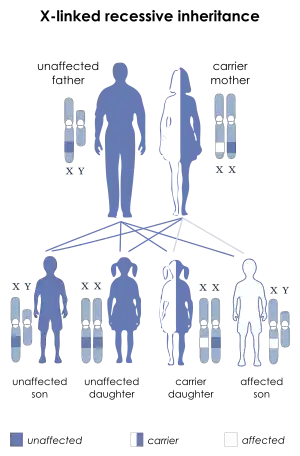

| This condition is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner | |

| Usual onset | Infancy |

SCARF syndrome is a rare syndrome characterized by skeletal abnormalities, cutis laxa, craniostenosis, ambiguous genitalia, psychomotor retardation, and facial abnormalities. These characteristics are what make up the acronym SCARF.[2] It shares some features with Lenz-Majewski hyperostotic dwarfism. It is a very rare disease with an incidence rate of approximately one in a million newborns.[3] It has been clinically described in two males who were maternal cousins, as well as a 3-month old female.[4][3] Babies affected by this syndrome tend to have very loose skin, giving them an elderly facial appearance. Possible complications include dyspnea, abdominal hernia, heart disorders, joint disorders, and dislocations of multiple joints.[3] It is believed that this disease's inheritance is X-linked recessive.[4]

Signs & Symptoms

The most characteristic signs and symptoms of SCARF syndrome are the ones described by the acronym. This includes skeletal abnormalities, cutis laxa, craniostenosis, ambiguous genitalia, psychomotor retardation, and facial abnormalities.[4] The severity of the symptoms will vary from person to person.[5] Symptoms will present similarly in both males and females, other than specific genitourinary symptoms.

Symptoms

- Facial

- Long philtrum

- Small chin

- Ptosis

- Epicanthal folds

- Strabismus

- High, broad nasal root

- Enamel hypoplasia

- Neck

- Excess nuchal skin

- Neck webs

- Short neck

- Chest

- Barrel-shaped

- Short sternum

- Pectus carinatum

- Hypoplastic nipples

- Abdomen

- Skeletal

- Abnormally-shaped vertebrae

- Craniosynostosis

- Genitourinary

- Skin, Hair, and Nails

- Cutis Laxa

- Sparse hair

- Neurological

- Mental retardation

- mild to moderate

- Mental retardation

(Symptoms were obtained from OMIM catalog[5])

Face abnormality and deformity.

Face abnormality and deformity.

Strabismus is a condition where the eyes are not aligned correctly, also known as "crossed-eyes." It is a common facial symptom of SCARF.[7]

Strabismus is a condition where the eyes are not aligned correctly, also known as "crossed-eyes." It is a common facial symptom of SCARF.[7] Ambiguous genitalia is a trademark symptom of SCARF syndrome, presented in both males and females.[8] The figure above shows clitoromegaly and hyperpigmentation.

Ambiguous genitalia is a trademark symptom of SCARF syndrome, presented in both males and females.[8] The figure above shows clitoromegaly and hyperpigmentation.

Causes

While the specific cause of SCARF syndrome is unknown, it has been deemed as a genetic disorder. It is believed to be typically inherited, and transmitted as both a recessive and dominant gene.[8]

Pathophysiology

The exact genetic mutation responsible for SCARF syndrome is unknown at this time. However, the mode of inheritance is perceived to be X-linked recessive because the first two cases reported of this syndrome were in two male cousins, who were related through their mothers.[8] This means that the gene that is associated with this disorder is located on the X chromosome.[9] Since males have only one X chromosome, only a single mutation is needed to cause this disorder. In contrast, females would require a mutation on both of their X chromosomes, which is a very rare occurrence. Therefore, SCARF syndrome and X-linked recessive disorders are more common in males.[9]

Cutis laxa, one of the most common symptoms associated with SCARF syndrome, is caused by mutations in several different genes. These genes include ATP6V0A2, ATP7A, EFEMP2, ELN, and FBLN5. These genes are responsible for elastic fibers, specifically how they are formed and their function. Elastic fibers allow the skin to stretch, help the lungs expand and contract, as well assist arteries in managing blood flow at high blood pressures. The mode of inheritance for cutis laxa may be X-linked, autosomal dominant, or autosomal recessive. Cutis laxa is known to be the cause of many of the complications associated with SCARF syndrome such as congestive heart failure, respiratory failure, and dysfunction of gastrointestinal and urinary tract.[10]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis relies on clinical presentations, physical examination, extensive evaluation of past medical history and family history, and karyotype testing. A 46,XX compatibility is an expected finding of the karyotype test. Laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging are typically insignificant for diagnosis. The relationship of the parents as well as family history of X-linked, autosomal dominant, and autosomal disorders should be considered to confirm SCARF syndrome.[3]

Management

Due to the fact that the syndrome is a genetic condition, there is no specific cure for this syndrome. Treatment is not for the disease itself, but more for management of the associated signs and symptoms of SCARF syndrome and its complications.

The main risk factor is previous family history. This does not guarantee that one will inherit the disease, but it is much more likely compared to someone with no family history. No other risk factors have been identified. Due to this reason, there are not many preventative measures that can be done.

If there is family history of the syndrome, genetic counseling should be considered before planning children to assess the risk of passing the disease onto future generations. Regular blood tests and physical examinations should be done as well to ensure no change in health status.[9]

Prognosis

The prognosis of SCARF syndrome depends on the severity of the signs and symptoms experienced, as well as if there are any associated complications. If the symptoms are mild, the prognosis will be better than that of someone with symptoms that are severe. There is no general prognosis for SCARF syndrome and it should be assessed independently for each case.[9]

Epidemiology

This syndrome is very rare with a prevalence rate of less than 1/1000000 worldwide.[11] The age of onset is typically neonatal or during infancy, but there has been a case reported in a 7-year-old male as well.[11][8] There is no evidence that the syndrome is more prevalent in a specific ethnicity, but it is more prevalent in males due to its X-linked recessive inheritance. Since males only have one X chromosome, this means that only one mutation is required for the syndrome to be inherited. Females have two X chromosomes, which means that the mutation must be present on both chromosomes in order to be inherited.[9]

Current Research

There is no current research exclusive to SCARF syndrome. However, research is being actively conducted on finding a treatment and prevention method for both inherited and acquired genetic disorders.[9] This includes research in the Netherlands on the genetic causes of facial abnormalities and its associated complications and symptoms.[12][13] The study involves the identification of new casual genes related to craniosynostosis including EFNB1 and TCF12 as well as genes involved in rare craniofacial malformations, including ALX3 and RAB23. This research can help identify other genes possibly linked to the development of SCARF syndrome. There is a current clinical trial in the United Kingdom that involves the use of Sarilumab injections for the treatment of musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders.[14] This clinical trial has the potential of developing a treatment that could be applied to numerous disorders of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue, such as SCARF syndrome.

References

- ↑ "SCARF syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ↑ "Scarf Syndrome disease: Malacards - Research Articles, Drugs, Genes, Clinical Trials". www.malacards.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 Rahimpour, Masoume; Sohrabi, Mohammad bager; Kalhor, Sulmaz; Khosravi, Hossein ali; Zolfaghari, Poone; Yahyaei, Elahe (2014-03-16). "A rare case report: SCARF syndrome". Clinical Case Reports. 2 (3): 74–76. doi:10.1002/ccr3.61. ISSN 2050-0904. PMC 4184596. PMID 25356252.

- 1 2 3 "SCARF syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- 1 2 3 "OMIM Clinical Synopsis - 312830 - SCARF SYNDROME". omim.org. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ↑ CDC (2019-12-04). "Facts about Craniosynostosis | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2021-01-07. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

- ↑ "Strabismus (crossed eyes)". www.aoa.org. Archived from the original on 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Koppe, Roswitha; Kaplan, Paige; Hunter, Alasdair; MacMurray, Brock (1989). "Ambiguous genitalia associated with skeletal abnormalities, cutis laxa, craniostenosis, psychomotor retardation, and facial abnormalities (SCARF syndrome)". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 34 (3): 305–312. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320340302. ISSN 1096-8628. PMID 2596519. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Purohit, Maulik (2018-04-28). "SCARF Syndrome". www.dovemed.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ↑ "Cutis laxa: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- 1 2 "Orphanet: SCARF syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ↑ Mathijssen, Irene. "Genetic causes of craniofacial anomalies" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ↑ Mathijssen, Irene. "Disturbed breathing in craniofacial disorders" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ↑ "Orphanet: An Open label, Sequential, Ascending, Repeated Dose finding Study of Sarilumab, Administered with Subcutaneous SC Injection, in Children and Adolescents, Aged 2 to 17 Years, with Polyarticular course Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis pcJIA Followed by an Extension Phase GB". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|