Pectus carinatum

| Pectus carinatum | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Pigeon chest, pectus cavernatum, bird chest, convex chest | |

| |

| Severe case of pectus carinatum | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

Pectus carinatum, also called pigeon chest, is a malformation of the chest characterized by a protrusion of the sternum and ribs. It is distinct from the related malformation pectus excavatum.

Signs and symptoms

People with pectus carinatum usually develop normal hearts and lungs, but the malformation may prevent these from functioning optimally. In moderate to severe cases of pectus carinatum, the chest wall is rigidly held in an outward position. Thus, respirations are inefficient and the individual needs to use the accessory muscles for respiration, rather than normal chest muscles, during strenuous exercise. This negatively affects gas exchange and causes a decrease in stamina. Children with pectus malformations often tire sooner than their peers due to shortness of breath and fatigue. Commonly concurrent is mild to moderate asthma.

Some children with pectus carinatum also have scoliosis (i.e., curvature of the spine). Some have mitral valve prolapse, a condition in which the heart mitral valve functions abnormally. Connective tissue disorders involving structural abnormalities of the major blood vessels and heart valves are also seen. Although rarely seen, some children have other connective tissue disorders, including arthritis, visual impairment and healing impairment.

Apart from the possible physiologic consequences, pectus malformations can have a significant psychologic impact. Some people, especially those with milder cases, live happily with pectus carinatum. For others, though, the shape of the chest can damage their self-image and confidence, possibly disrupting social connections and causing them to feel uncomfortable throughout adolescence and adulthood. As the child grows older, bodybuilding techniques may be useful for balancing visual impact.

A less common variant of pectus carinatum is pectus arcuatum (also called type 2 pectus excavatum, chondromanubrial malformation or Currarino–Silverman syndrome or pouter pigeon malformation), which produces a manubrial and upper sternal protrusion,[2] particularly also at the sternal angle.[3] Pectus arcuatum is often confused with a combination of pectus carinatum and pectus excavatum, but in pectus arcuatum the visual appearance is characterized by a protrusion of the costal cartilages and there is no depression of the sternum.[4]

Causes

Pectus carinatum is an overgrowth of costal cartilage causing the sternum to protrude forward. It primarily occurs among four different patient groups, and males are more frequently affected than females. Most commonly, pectus carinatum develops in 11-to-14-year-old pubertal males undergoing a growth spurt. Some parents report that their child's pectus carinatum seemingly popped up overnight. Second most common is the presence of pectus carinatum at or shortly after birth. The condition may be evident in newborns as a rounded anterior chest wall. As the child reaches age 2 or 3 years of age, the outward sternal protrusion becomes more pronounced. Pectus carinatum can also be caused by vitamin D deficiency in children (Rickets) due to deposition of unmineralized osteoid. Least common is a pectus carinatum malformation following open-heart surgery or in children with poorly controlled bronchial asthma.

Pectus carinatum is generally a solitary, non-syndromic abnormality. However, the condition may be present in association with other syndromes: Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Loeys–Dietz syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Morquio syndrome, trisomy 18, trisomy 21, homocystinuria, osteogenesis imperfecta, multiple lentigines syndrome (LEOPARD syndrome), Sly syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type VII), and scoliosis.

In about 25% of cases of pectus carinatum, the patient has a family member with the condition.

Diagnosis

The pectus carinatum can be easily diagnosed by certain tests like a CT scan (2D and 3D). It may then be found out that the rib cage is in normal structure. If there is more than average growth of sternum than pectus carinatum protrudes. Also it is of two types, as pectus carinatum is symmetrical or unsymmetrical. On the basis of that further treatment is given to the patient.

Treatment

External bracing technique

The use of orthotic bracing, pioneered by Sydney Haje as of 1977, is finding increasing acceptance as an alternative to surgery in select cases of pectus carinatum.[5] In children, teenagers, and young adults who have pectus carinatum and are motivated to avoid surgery, the use of a customized chest-wall brace that applies direct pressure on the protruding area of the chest produces excellent outcomes. Willingness to wear the brace as required is essential for the success of this treatment approach. The brace works in much the same way as orthodontics (braces that correct the alignment of teeth). The brace consists of front and back compression plates that are anchored to aluminum bars. These bars are bound together by a tightening mechanism which varies from brace to brace. This device is easily hidden under clothing and must be worn from 14 to 24 hours a day. The wearing time varies with each brace manufacturer and the managing physicians protocol, which could be based on the severity of the carinatum malformation (mild moderate severe) and if it is symmetric or asymmetric.

Depending on the manufacturer and/or the patient's preference, the brace may be worn on the skin or it may be worn over a body 'sock' or sleeve called a Bracemate, specifically designed to be worn under braces. A physician or orthotist or brace manufacturer's representative can show how to check to see if the brace is in correct position on the chest.

Bracing is becoming more popular over surgery for pectus carinatum, mostly because it eliminates the risks that accompany surgery. The prescribing of bracing as a treatment for pectus carinatum has 'trickled down' from both paediatric and thoracic surgeons to the family physician and pediatricians again due to its lower risks and well-documented very high success results. The pectus carinatum guideline of 2012 of the American Pediatric Surgical Association has stated: "As reconstructive therapy for the compliant pectus [carinatum] malformation, nonoperative compressive orthotic bracing is usually an appropriate first line of therapy as it does not preclude the operative option. For appropriate candidates, orthotic bracing of chest wall malformations can reasonably be expected to prevent worsening of the malformation and often results in a lasting correction of the malformation. Orthotic bracing is often successful in prepubertal children whose chest wall is compliant. Expert opinion suggests that the noncompliant chest wall malformation or significant asymmetry of the pectus carinatum malformation caused by a concomitant excavatum-type malformation may not respond to orthotic bracing."[6]

Regular supervision during the bracing period is required for optimal results. Adjustments may be needed to the brace as the child grows and the pectus improves.

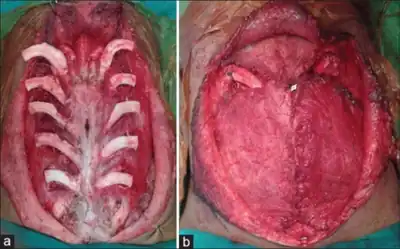

Surgical

For patients with severe pectus carinatum, surgery may be necessary. However bracing could and may still be the first line of treatment. Some severe cases treated with bracing may result in just enough improvement that patient is happy with the outcome and may not want surgery afterwards. If bracing should fail for whatever reason then surgery would be the next step. The two most common procedures are the Ravitch technique and the Reverse Nuss procedure.

A modified Ravitch technique uses bioabsorbable material and postoperative bracing, and in some cases a diced rib cartilage graft technique.[7]

The Nuss was developed by Donald Nuss at the Children's Hospital of the King's Daughters in Norfolk, Va. The Nuss is primarily used for Pectus Excavatum, but has recently been revised for use in some cases of PC, primarily when the malformation is symmetrical.

Other options

After adolescence, some men and women use bodybuilding as a means to hide their malformation. Some women find that their breasts, if large enough, serve the same purpose. Some plastic surgeons perform breast augmentation to disguise mild to moderate cases in women. Bodybuilding is suggested for people with symmetrical pectus carinatum.[8]

Prognosis

Pectus malformations usually become more severe during adolescent growth years and may worsen throughout adult life. The secondary effects, such as scoliosis and cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions, may worsen with advancing age.

Body building exercises (often attempted to cover the defect with pectoral muscles) will not alter the ribs and cartilage of the chest wall, and are generally considered not harmful.

Most insurance companies no longer consider chest wall malformations like pectus carinatum to be purely cosmetic conditions. While the psychologic impact of any malformation is real and must be addressed, the physiological concerns must take precedence. The possibility of lifelong cardiopulmonary difficulties is serious enough to warrant a visit to a thoracic surgeon.

Epidemiology

Pectus malformations are common; about 1 in 400 people have a pectus disorder.[9]

Pectus carinatum is rarer than pectus excavatum, another pectus disorder, occurring in only about 20% of people with pectus malformations.[9] About four out of five patients are males.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "pectus carinatum". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- ↑ Restrepo CS, Martinez S, Lemos DF, Washington L, McAdams HP, Vargas D, Lemos JA, Carrillo JA, Diethelm L (2009). "Imaging appearances of the sternum and sternoclavicular joints". Radiographics. 29 (3): 839–59. doi:10.1148/rg.293055136. PMID 19448119.

- ↑ Anton H. Schwabegger (15 September 2011). Congenital Thoracic Wall Deformities: Diagnosis, Therapy and Current Developments. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-3-211-99138-1.

- ↑ Kuzmichev, Vladimir; Ershova, Ksenia; Adamyan, Ruben (16 March 2016). "Surgical correction of pectus arcuatum". Journal of Visualized Surgery. 2: 55. doi:10.21037/jovs.2016.02.28. PMC 5638405. PMID 29078483.

- ↑ Desmarais TJ, Keller MS (2013). "Pectus carinatum". Current Opinion in Pediatrics (Review). 25 (3): 375–81. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283604088. PMID 23657247. S2CID 46604820.

- ↑ "Pectus Carinatum Guideline – Approved by the APSA Board of Governors" (PDF). American Pediatric Surgical Association. 8 August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ Del Frari B, Sigl S, Schwabegger AH (2016). "Complications Related to Pectus Carinatum Correction: Lessons Learned from 15 Years' Experience. Management and Literature Review". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (Review). 138 (2): 317e–29e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002414. PMID 27465193. S2CID 5385408.

- ↑ carinatum.com Archived 2020-08-11 at the Wayback Machine, Pectus Carinatum Exercise.

- 1 2 "Pediatric Surgery | Mattel Children's Hospital UCLA - Los Angeles, CA". Surgery.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-09-01. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- ↑ "Pectus Carinatum, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center". Cincinnatichildrens.org. 2007-09-26. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |