Loeys–Dietz syndrome

| Loeys–Dietz syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Aortic aneurysm syndrome due to TGF-beta receptors anomalies | |

| |

| This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner[1] | |

| Pronunciation |

|

Loeys–Dietz syndrome (LDS) is an autosomal dominant genetic connective tissue disorder, with features similar to Marfan syndrome and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.[3][4][5] It is characterised by deformities of the skin, head, bone and blood vessels, in addition to aneurysms and dissection in the weakened layers of the wall of the aorta.[6] Aneurysms and dissections also can occur in arteries other than the aorta. Because aneurysms in children tend to rupture early, children are at greater risk for dying if the syndrome is not identified. Surgery to repair aortic aneurysms is essential for treatment.

There are five types of the syndrome, labelled types I through V, which are distinguished by their genetic cause. Type 1, Type 2, Type 3, Type 4 and Type 5 are caused by mutations in TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD3, TGFB2, and TGFB3 respectively. These five genes encoding transforming growth factors play a role in cell signaling that promotes growth and development of the body's tissues. Mutations of these genes cause production of proteins without function. The skin cells for individuals with Loeys–Dietz syndrome are not able to produce collagen, the protein that allows skin cells to be strong and elastic. This causes these individuals to be susceptible to different tears in the skin such as hernias. Although the disorder has an autosomal pattern of inheritance, this disorder results from a new gene mutation in 75% of cases and occurs in people with no history of the disorder in their family. In other cases it is inherited from one affected parent.[7]

Loeys–Dietz syndrome was identified and characterized by pediatric geneticists Bart Loeys and Harry "Hal" Dietz at Johns Hopkins University in 2005.

Signs and symptoms

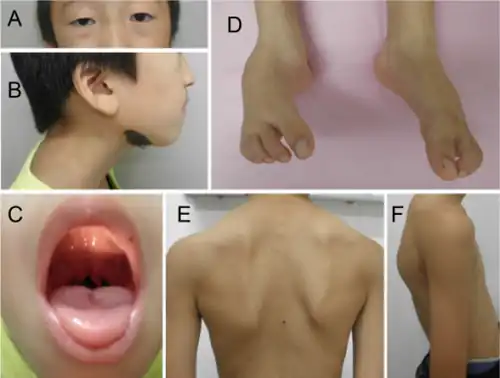

There is considerable variability in the phenotype of Loeys–Dietz syndrome, from mild features to severe systemic abnormalities. The primary manifestations of Loeys–Dietz syndrome are arterial tortuosity (winding course of blood vessels), widely spaced eyes (hypertelorism), wide or split uvula, and aneurysms at the aortic root. Other features may include cleft palate and a blue/gray appearance of the white of the eyes. Cardiac defects and club foot may be noted at birth.[8]

There is overlap in the manifestations of Loeys–Dietz and Marfan syndromes, including increased risk of ascending aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection, abnormally long limbs and fingers, and dural ectasia (a gradual stretching and weakening of the dura mater that can cause abdominal and leg pain). Findings of hypertelorism (widely spaced eyes), bifid or split uvula, and skin findings such as easy bruising or abnormal scars may distinguish Loeys–Dietz from Marfan syndrome.

Affected individuals often develop immune system related problems such as allergies to food, asthma, hay fever, and inflammatory disorders such as eczema or inflammatory bowel disease.

Findings of Loeys–Dietz syndrome may include:

- Skeletal/spinal malformations: craniosynostosis, Scoliosis, spinal instability and spondylolisthesis, Kyphosis

- Sternal abnormalities: pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum

- Contractures of fingers and toes (camptodactyly)

- Long fingers and lax joints

- Weakened or missing eye muscles (strabismus)

- Club foot

- Premature fusion of the skull bones (craniosynostosis)

- Joint hypermobility

- Congenital heart problems including patent ductus arteriosus (connection between the aorta and the lung circulation) and atrial septal defect (connection between heart chambers)

- Translucency of the skin with velvety texture

- Abnormal junction of the brain and medulla (Arnold–Chiari malformation)

- Bicuspid aortic valves

- Criss-crossed pulmonary arteries

Cause

Types (old nomenclature)

Several genetic causes of Loeys–Dietz syndrome have been identified. A de novo mutation in TGFB3, a ligand of the TGF β pathway, was identified in an individual with a syndrome presenting partially overlapping symptoms with Marfan Syndrome and Loeys–Dietz Syndrome.[9]

| Type | Gene | Locus | OMIM | Description |

| 1A | TGFBR1 | 9q22 | 609192 | Also known as Furlong disease |

| 1B | TGFBR2 | 3p22 | 610168 | |

| 2A | TGFBR1 | 9q22 | 608967 | |

| 2B | TGFBR2 | 3p22 | 610380 | Previously known as Marfan syndrome type 2 |

| 3 | SMAD3 | 613795 | Also known as Aneurysms-osteoarthritis syndrome | |

| 4 | TGFB2 | 614816 | ||

| 5 | TGFB3 | 615582 |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis involves consideration of physical features and genetic testing. Presence of split uvula is a differentiating characteristic from Marfan Syndrome, as well as the severity of the heart defects. Loeys–Dietz Syndrome patients have more severe heart involvement and it is advised that they be treated for enlarged aorta earlier due to the increased risk of early rupture in Loeys–Dietz patients. Because different people express different combinations of symptoms and the syndrome was first identified in 2005, many doctors may not be aware of its existence.

Treatment

As there is no known cure, Loeys–Dietz syndrome is a lifelong condition. Due to the high risk of death from aortic aneurysm rupture, patients should be followed closely to monitor aneurysm formation, which can then be corrected with vascular surgery. Previous research in laboratory mice has suggested that the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan, which appears to block TGF-beta activity, can slow or halt the formation of aortic aneurysms in Marfan syndrome. A large clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health is currently underway to explore the use of losartan to prevent aneurysms in Marfan syndrome patients. Both Marfan syndrome and Loeys–Dietz syndrome are associated with increased TGF-beta signaling in the vessel wall. Therefore, losartan also holds promise for the treatment of Loeys–Dietz syndrome. In those patients in which losartan is not halting the growth of the aorta, irbesartan has been shown to work and is currently also being studied and prescribed for some patients with this condition.

If an increased heart rate is present, a cardioselective beta-1 blocker, with or without losartan, is sometimes prescribed to reduce the heart rate to prevent any extra pressure on the tissue of the aorta. Likewise, strenuous physical activity is discouraged in patients, especially weight lifting and contact sports.[10]

Epidemiology

The incidence of Loeys–Dietz syndrome is unknown; however, Type 1 and 2 appear to be the most common.[7]

References

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Loeys Dietz syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ "Research and Treatment | Loeys-Dietz Syndrome". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 10 August 2018. Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ↑ Loeys BL, Schwarze U, Holm T, et al. (2006). "Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-beta receptor". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (8): 788–98. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055695. PMID 16928994.

- ↑ LeMaire SA, Pannu H, Tran-Fadulu V, Carter SA, Coselli JS, Milewicz DM (2007). "Severe aortic and arterial aneurysms associated with a TGFBR2 mutation". Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. 4 (3): 167–71. doi:10.1038/ncpcardio0797. PMC 2561071. PMID 17330129.

- ↑ Loeys BL, Chen J, Neptune ER, et al. (March 2005). "A syndrome of altered cardiovascular, craniofacial, neurocognitive and skeletal development caused by mutations in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2". Nat. Genet. 37 (3): 275–81. doi:10.1038/ng1511. hdl:1854/LU-330238. PMID 15731757. S2CID 24499542. Archived from the original on 2019-12-12. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ↑ Madan-Khetarpal, Georgianne; Arnold, Georgianne; Oritz, Damara (2023). "1. Genetic disorders and dysmorphic conditions". In Zitelli, Basil J.; McIntire, Sara C.; Nowalk, Andrew J.; Garrison, Jessica (eds.). Zitelli and Davis' Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-323-77788-9. Archived from the original on 2022-12-19. Retrieved 2022-12-19.

- 1 2 Loeys–Dietz syndrome at NLM Genetics Home Reference

- ↑ "Loeys-Dietz Syndrome". The Marfan Foundation. 27 June 2013. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ↑ Rienhoff HY, Yeo C-Y, Morissette R, Khrebtukova I, Melnick J, Luo S, Leng N, Kim Y-J, Schroth G, Westwick J, Vogel H, McDonnell N, Hall JG, Whitman M. 2013. A mutation in TGFB3 associated with a syndrome of low muscle mass, growth retardation, distal arthrogryposis, and clinical features overlapping with Marfan and Loeys–Dietz syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 161A:2040–2046.

- ↑ Loeys, BL; Dietz, HC (1993). "Loeys-Dietz Syndrome". In Adam, MP; Ardinger, HH; Pagon, RA (eds.). GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

Further reading

- Bertoli-Avella, A. M; Gillis, E; Morisaki, H; Verhagen, J. M. A; De Graaf, B. M; Van De Beek, G; Gallo, E; Kruithof, B. P. T; Venselaar, H; Myers, L. A; Laga, S; Doyle, A. J; Oswald, G; Van Cappellen, G. W. A; Yamanaka, I; Van Der Helm, R. M; Beverloo, B; De Klein, A; Pardo, L; Lammens, M; Evers, C; Devriendt, K; Dumoulein, M; Timmermans, J; Bruggenwirth, H. T; Verheijen, F; Rodrigus, I; Baynam, G; Kempers, M; et al. (2015). "Mutations in a TGF-β ligand, TGFB3, cause syndromic aortic aneurysms and dissections". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 65 (13): 1324–1336. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.040. PMC 4380321. PMID 25835445.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|