Superficial vein thrombosis

| Superficial vein thrombosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Superficial thrombophlebitis | |

| |

| Greater saphenous vein thrombosis | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Red, warm, tender area overlying a vein, hard vein[1] |

| Complications | Pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT)[1] |

| Usual onset | 60 years old[1] |

| Risk factors | Varicose veins, pregnancy, factor V Leiden mutation, cancer, birth control pills, obesity, recent surgery, heart failure[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, confirmed by ultrasound[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Cellulitis, lymphangitis, lymphedema, vasculitis, tendonitis[1] |

| Treatment | NSAIDs, heat,blood thinners, compression stockings[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally good outcome[1] |

| Frequency | 6 per 1,000per year[1] |

Superficial vein thrombosis (SVT) is a blood clot in a superficial vein (near the skin).[1] Symptoms typically include a red, warm, inflamed, and tender area overlying a vein.[1] The vein often feels hard.[1] Most commonly the legs are involved.[1] Complications may include pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT).[1]

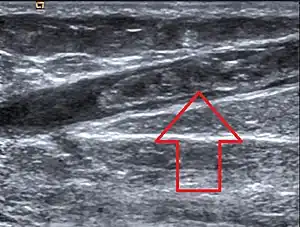

Risk factors include varicose veins, pregnancy, certain genetic conditions such as factor V Leiden mutation, cancer, birth control pills, obesity, recent surgery, and heart failure.[1] The underlying mechanism may involve increased clotting, decreased movement, or injury to the vein.[1] The greater saphenous vein is involved about 70% of the time, and the small saphenous vein about 15% of the time.[1] It is a type of thrombophlebitis.[2] Diagnosis is often based on symptoms and confirmed by ultrasound.[1]

In those with low risk disease treatment is often with NSAIDs, heat, and blood thinners.[1] In those with higher risk disease treatment with fondaparinux or rivaroxaban for 45 days is recommended.[1][3] Compression stockings may be recommended.[1] SVT generally has a good outcome.[1]

One study found a rate of 6 per 1,000 people per year.[1] Women are more commonly affected than men.[1] The typical age of those affected is 60.[1] Those with multiple episodes, known as Trousseau syndrome, should be investigated for cancer.[1] SVT was first described in ancient India by Sushruta.[4]

Signs and symptoms

.jpg.webp)

SVT is recognized by the presence of pain, warmth, redness, and tenderness over a superficial vein.[5] The SVT may present as a "cord-like" structure upon palpation.[5] The affected vein may be hard along its entire length.[6] SVTs tend to involve the legs, though they can affect any superficial vein (e.g. those in the arms).[5]

When it occurs in the leg, the great saphenous vein is usually involved, although other locations are possible.[7]

Complications

SVT in the lower extremities can lead to a complication in which the clot travels to the lungs, called pulmonary embolism (PE).[8] This is because lower limb SVTs can migrate from superficial veins into deeper veins.[8] In a French population, the percent of people with SVTs that also had PEs was 4.7%.[8] In the same population, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) was found in 24.6% of people with SVTs.[8] However, because superficial veins lack muscular support, any clots that form are far less likely to be squeezed by muscle contraction, dislodged, and induce a PE.[6]

SVTs can recur after they resolve, which is termed "migratory thrombophlebitis".[6] Migratory thrombophlebitis is a complication that may be due to more serious disorders, such as cancer and other hypercoagulable states.[6] Migratory thrombophlebitis (recurrent SVT) and cancer are the hallmarks of Trousseau syndrome.[6]

Causes

SVTs of the legs are often due to varicose veins, though most people with varicose veins do not develop SVTs.[6] SVTs of the arms are often due to the placement of intravenous catheters.[6]

Many of the risk factors that are associated with SVT are also associated with other thrombotic conditions (e.g. DVT). These risk factors include age, cancer, history of thromboembolism, pregnancy, use of oral contraceptive medications (containing estrogen),[9] hormone replacement therapy, recent surgery, and certain autoimmune diseases (especially Behçet's and Buerger's diseases).[8] Other risk factors include immobilization (stasis) and laparoscopy.[5]

Hypercoagulable states due to genetic conditions that increase the risk of clotting may contribute to the development of SVT, such as factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210A mutation, and protein C, S, and antithrombin III and factor XII deficiency.[5]

Mechanism

The mechanism for the development of an SVT depends upon the specific etiology of the SVT. For example, varicose veins and prolonged bed rest both may induce SVTs due to slowing the flow of blood through superficial veins.[5]

Diagnosis

SVTs may be diagnosed based upon clinical criteria by a healthcare professional.[5] A more specific evaluation can be made by ultrasound.[5] An ultrasound can be useful in situations in which an SVT occurs above the knee and is not associated with a varicose vein, because ultrasounds can detect more serious clots like DVTs.[6] The diagnostic utility of D-dimer testing in the setting of SVTs has yet to be fully established.[8]

Classification

SVTs can be classified as either varicose vein (VV) or non-varicose (NV) associated.[5] NV-SVTs are more likely to be associated with genetic procoagulable states compared to VV-SVTs.[5] SVTs can also be classified by pathophysiology. That is, primary SVTs are characterized by inflammation that is localized to the veins. Secondary SVTs are characterized by systemic inflammatory processes.[5]

A subclass of SVTs are septic thrombophlebitis, which are SVTs that occur in the setting of an infection.[11]

Treatment

The goal of treatment in SVT is to reduce local inflammation and prevent the SVT from extending from its point of origin.[5] Treatment may entail the use of compression, physical activity, medications, or surgical interventions.[5] The optimal treatment for many SVT sites (i.e. upper limbs, neck, abdominal and thoracic walls, and the penis) has not been determined.[8]

Compression

Multiple compression bandages exist. Fixed compression bandages, adhesive short stretch bandages, and graduated elastic compression stockings have all be used in the treatment of SVTs.[5] The benefit of compression stockings is unclear, though they are frequently used.[8]

Physical activity

Inactivity is contraindicated in the aftermath of an SVT.[5] Uninterrupted periods of sitting or standing may cause the SVT to elongate from its point of origin, increasing the risk for complications and clinical worsening.[5]

Medications

Medications used for the treatment of SVT include anticoagulants, NSAIDs (except aspirin), antibiotics, and corticosteroids.[5]

Blood thinners

SVTs that occur within the great saphenous vein within 3 cm of the saphenofemoral junction are considered to be equivalent in risk to DVTs.[8] These high risk SVTs are treated identically with therapeutic anticoagulation.[8] Anticoagulation is also used for intermediate risk SVTs that are greater than 3 cm from the saphenofemoral junction or are greater than 4–5 cm in length.[8]

Anticoagulation for high risk SVTs includes the use of vitamin K antagonists or novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for 3 months.[8] Anticoagulation for intermediate risk SVTs includes fondaparinux 2.5 mg daily for 45 days or the use of intermediate to therapeutic dose low molecular weight heparin for 4–6 weeks.[8]

NSAIDs

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) can be used in both oral or topical formulations for the relief of SVT symptoms.[8] The British Committee for Standards in Haematology guidelines recommend the use of NSAIDs for low-risk SVTs (thrombus <4–5 cm in length, no additional risk factors for thromboembolic events).[8] NSAIDs are used for treatment durations of 8–12 days.[8]

Other

Antibiotics are used in the treatment of septic SVT.[5] Corticosteroids are used for the treatment of SVTs in the setting of vasculitic and autoimmune syndromes.[5]

Surgery

Surgical interventions are used for both symptomatic relief of the SVT as well as for preventing the development of more serious complications (e.g. pulmonary embolism).[8] Surgical interventions include ligation of the saphenofemoral junction, ligation and stripping of the affected veins, and local thrombectomy.[8] Because of the risk of symptomatic pulmonary embolism with surgery itself, surgical interventions are not recommended for the treatment of lower limb SVTs by the 2012 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines and the 2012 British Committee for Standards in Haematology guidelines.[8] The use of surgery for the treatment of SVT is controversial.[12]

Prognosis

SVT is often a mild, self-resolving medical condition.[5] The inflammatory reaction may last up to 2–3 weeks, with possible recanalization of the thrombosed vein occurring in 6–8 weeks.[5] The superficial vein may continue to be hyperpigmented for several months following the initial event.[5]

Epidemiology

In a French population, SVT occurred in 0.64 per 1000 persons per year.[8]

Some 125,000 cases a year have been reported in the United States, but actual incidence of spontaneous thrombophlebitis is unknown.[13] A fourfold increased incidence from the third to the eight decade in men and a preponderance among women of approximately 55-70%.[14] The average mean age of affected people is 60 years.ref name="Decousus_2003">Decousus H, Epinat M, Guillot K, Quenet S, Boissier C, Tardy B (September 2003). "Superficial vein thrombosis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 9 (5): 393–7. doi:10.1097/00063198-200309000-00009. PMID 12904709.</ref>

History

SVTs have been historically considered to be benign diseases, for which treatment was limited to conservative measures.[12] However, an increased awareness of the potential risks of SVTs developing into more serious complications has prompted more research into the diagnosis, classification, and treatment of SVTs.[12]

Research

A Cochrane review recommends that future research investigate the utility of oral, topical, and surgical treatments for preventing the progression of SVTs and the development of thromboembolic complications.[15][16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Czysz, A; Higbee, SL (January 2021). "Superficial Thrombophlebitis". PMID 32310477.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Thrombophlebitis - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Di Nisio, M; Wichers, IM; Middeldorp, S (25 February 2018). "Treatment for superficial thrombophlebitis of the leg". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2: CD004982. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004982.pub6. PMID 29478266.

- ↑ Vaidyanathan, Subramoniam; Menon, Riju Ramachandran; Jacob, Pradeep; John, Binni (2014). Chronic Venous Disorders of the Lower Limbs: A Surgical Approach. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-81-322-1991-0. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Kalodiki, E; Stvrtinova, V; Allegra, C; Andreozzi, GM; Antignani, P-L; Avram, R; Brkljacic, B; Cadariou, F; Dzsinich, C; Fareed, J; Gaspar, L; Geroulakos, G; Jawien, A; Kozak, M; Lattimer, CR; Minar, E; Partsch, H; Passariello, F; Patel, M; Pecsvarady, Z; Poredos, P; Roztocil, K; Scuderi, A; Sparovec, M; Szostek, M; Skorski, M (2012). "Superficial vein thrombosis: a consensus statement". International Angiology. 31 (3): 203–216. PMID 22634973.(subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Superficial Venous Thrombosis – Heart and Blood Vessel Disorders – Merck Manuals Consumer Version". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ↑ Karwowski JK (November 2007). "How to manage thrombophlebitis of the lower extremities: why this malady warrants close attention". Contemporary Surgery. 63 (11): 552–8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Cosmi, B. (July 2015). "Management of superficial vein thrombosis". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 13 (7): 1175–1183. doi:10.1111/jth.12986. PMID 25903684.

- ↑ "Hormonal Birth Control and Blood Clot Risk – NWHN". NWHN. NWHN. 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ Smith B (27 March 2015). "UOTW #42". Ultrasound of the Week. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ Foris, LA; Bhimji, SS (June 2017). "Thrombophlebitis, Septic". StatPearls. PMID 28613482.

- 1 2 3 Sobreira, Marcone Lima; Yoshida, Winston Bonneti; Lastória, Sidnei (June 2008). "Tromboflebite superficial: epidemiologia, fisiopatologia, diagnóstico e tratamento". Jornal Vascular Brasileiro. 7 (2): 131–143. doi:10.1590/S1677-54492008000200007.

- ↑ Blumenberg RM, Barton E, Gelfand ML, Skudder P, Brennan J (February 1998). "Occult deep venous thrombosis complicating superficial thrombophlebitis". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 27 (2): 338–43. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70364-7. PMID 9510288.

- ↑ Coon WW, Willis PW, Keller JB (October 1973). "Venous thromboembolism and other venous disease in the Tecumseh community health study". Circulation. 48 (4): 839–46. doi:10.1161/01.cir.48.4.839. PMID 4744789.

- ↑ Di Nisio, Marcello; Wichers, Iris M.; Middeldorp, Saskia (2013-04-30). "Treatment for superficial thrombophlebitis of the leg". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD004982. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004982.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 23633322.

- ↑ Streiff MB, Bockenstedt PL, Cataland SR, et al. (2011). "Venous thromboembolic disease". J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 9 (7): 714–77. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2011.0062. PMC 3551573. PMID 21715723.