Sustainable Development Goal 2

| Sustainable Development Goal 2 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mission statement | "End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture" |

| Commercial? | No |

| Type of project | Non-Profit |

| Location | Global |

| Owner | Supported by United Nation & Owned by community |

| Founder | United Nations |

| Established | 2015 |

| Website | sdgs |

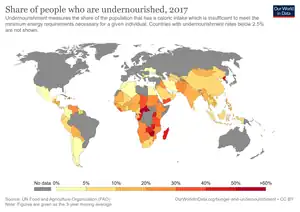

Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2 or Global Goal 2) aims to achieve "zero hunger". It is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations in 2015. The official wording is: "End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture".[1] SDG 2 highlights the complex inter-linkages between food security, nutrition, rural transformation and sustainable agriculture.[2] According to the United Nations, there are around 690 million people who are hungry, which accounts for 10 percent of the world population.[3] One in every nine people goes to bed hungry each night, including 20 million people currently at risk of famine in South Sudan, Somalia, Yemen and Nigeria.[4]

SDG 2 has eight targets and 14 indicators to measure progress.[5] The five "outcome targets" are: ending hunger and improving access to food; ending all forms of malnutrition; agricultural productivity; sustainable food production systems and resilient agricultural practices; and genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals; investments, research and technology. The three "means of achieving" targets include: addressing trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets and food commodity markets and their derivatives.[5]

Under-nutrition has been on the rise since 2015, after falling for decades.[6] This majorly results from the various stresses in food systems that include; climate shocks, the locust crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Those threats indirectly reduce the purchasing power and the capacity to produce and distribute food, which affects the most vulnerable populations and furthermore has reduced their accessibility to food.[7] Up to 142 million people in 2020, have suffered from undernourishment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[8] Stunting and wasting children statistics are likely to worsen with the pandemic.[9] In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic "may add between 83 and 132 million people to the total number of undernourished in the world by the end of 2020 depending on the economic growth scenario".[10]

The world is not on track to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030. "The signs of increasing hunger and food insecurity are a warning that there is considerable work to be done to make sure the world "leaves no one behind" on the road towards a world with zero hunger."[11] It is unlikely there will be an end to malnutrition in Africa by 2030.[12][13]

Background

In September 2015, the General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that included 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Building on the principle of "leaving no one behind", the new Agenda emphasizes a holistic approach to achieving sustainable development for all.[14] In September 2019, Heads of State and Government came together during the SDG Summit to renew their commitment to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. During this event, they acknowledged that the first four years of the implementation of the 2030 Agenda included major progress, but that overall, the world is not on track to deliver the SDGs.[15] This is when "the decade of action" and "delivery for sustainable development" was launched, demanding stakeholders to speed up the process and efforts of implementation.[14]

SDG 2 aims to end all forms of malnutrition and hunger by 2030 and ensure that everyone has sufficient food throughout the year, especially children. Chronic malnutrition, which affects an estimated 155 million children worldwide, also stunts children's brain and physical development and puts them at further risk of death, disease, and lack of success as adults.[16]

As of 2017, only 26 of 202 UN member countries were on track to meet the SDG target to eliminate undernourishment and malnourishment, while 20 percent have made no progress at all and nearly 70 percent have no or insufficient data to determine their progress.[16] "There is less than enough food produced today to feed every last one of us." According to FAO, there are almost 690 million people who remain chronically undernourished. This number has dropped by almost half in the past two decades because of rapid economic growth and increased agricultural productivity.[17]

Malnutrition and extreme hunger constitute a crucial barrier to sustainable development. Both create a trap from which people cannot escape. Hungry people are less productive and easily prone to diseases. As such, they will be unable to improve their livelihood.

SDG 2 lays the foundational way to sustaining the world's population and making sure that nobody will ever suffer from hunger. It should be done through promoting sustainable agriculture with modern technologies and fair distribution systems.[18] Innovations in agriculture are meant to ensure increase in food production and subsequent decrease in food loss and food waste.[19]

SDG 2 states that by 2030 people should achieve food security by ending hunger and all forms of malnutrition. This would be accomplished by doubling agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers (especially women and indigenous peoples), by ensuring sustainable food production systems, and by progressively improving land and soil quality. Agriculture is the single largest employer in the world, providing livelihoods for 40% of the global population. It is the largest source of income for poor rural households. Women make up about 43% of the agricultural labor force in developing countries, and over 50% in parts of Asia and Africa. However, women own only 20% of the land.

A report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) of 2013 stated that the emphasis of the SDGs should not be on ending poverty by 2030, but on eliminating hunger and under-nutrition by 2025.[20] The assertion is based on an analysis of experiences in China, Vietnam, Brazil, and Thailand. Three pathways to achieve this were identified: 1) agriculture-led; 2) social protection- and nutrition- intervention-led; or 3) a combination of both of these approaches.[20]

The World Food Program indicates that around 135 million people suffer from acute hunger caused by the climate change, man-made conflicts, and the economic downturns.[21] Around 690 million people across the globe are hungry or around 8.9% of the world population. [22] Sustainable food production system is achieved and implementing resilient agricultural practices aimed at increasing production and productivity. It also seeks to help in maintaining ecosystems and also strengthening capacity for climate change adaptation, drought, extreme weather, and other disasters.

Targets, indicators and progress

The UN has defined 8 targets and 13 indicators for SDG 2.[23] Four of them are to be achieved by the year 2030, one by the year 2020 and three have no target years. Each of the targets also has one or more indicators to measure progress. In total there are fourteen indicators for SDG 2. The six targets include ending hunger and increasing access to food (2.1), ending all forms of malnutrition (2.2), agricultural productivity (2.3), sustainable food production systems and resilient agricultural practices (2.4), genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals (2.5), investments, research and technology (2.a), trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets (2.b) and food commodity markets and their derivatives (2.c).

Target 2.1: Universal access to safe and nutritious food

The first target of SDG 2 is Target 2.1: "By 2030 end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round".[23]

It has two indicators:[25]

- Indicator 2.1.1: Prevalence of undernourishment.

- Indicator 2.1.2: Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population, based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES).[26]

Food insecurity is defined by the UN FAO as the "situation when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life."[27] The UN's FAO uses the prevalence of undernourishment as the main hunger indicator.[27]

In order to monitor SDG target 2.1 and measure food insecurity, the FAO got inspiration from many countries leading the way and scaled their systems to the global level. The approach that they used is based on a survey that reports specific conditions and behaviors related to constraints on access to food. The "Food Insecurity Experience Scale" (FIES) survey module is composed of eight questions, carefully selected and tested, and proven effective in measuring the severity of the food insecurity situation of respondents in different cultural, linguistic and development contexts.[11]

It is estimated that in 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic economic shocks will push between 83 and 132 million people into food insecurity.[28]: 26

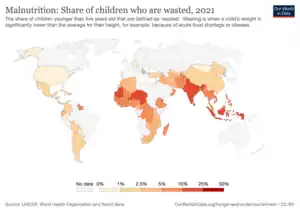

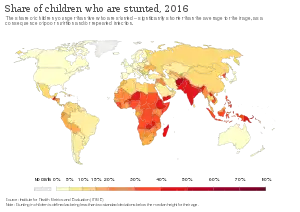

Target 2.2: End all forms of malnutrition

The full title of Target 2.2 is: "By 2030 end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving by 2025 the international agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under five years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and older persons."[23]

It has two indicators:[25]

- Indicator 2.2.1: Prevalence of stunting (height for age <-2 standard deviation from the median of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards) among children under 5 years of age)".

- Indicator 2.2.2: Prevalence of malnutrition (weight for height >+2 or <-2 standard deviation from the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards).

Stunted children are determined as having a height which falls below the median height-for-age of the World Health Organization's Child Growth Standards. A child is defined as "wasted" if their weight-for-height is more than two standard deviations below the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards. A child is defined as "overweight" if their weight-for-height is more than two standard deviations above the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards.[25]

Stunting is an indicator of severe malnutrition. The impacts of stunting on child development are considered to be irreversible beyond the first 1000 days of a child's life. Stunting can have severe impacts on both cognitive and physical development throughout a person's life.[29] Child stunting portrays linear growth and measures long-term growth faltering. According to the 2017 High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) Thematic review of SDG 2, there will be 130 million stunted children by 2025 if this trend continues. Furthermore, about 30 million will be above the global target, which is a 40% reduction in numbers of stunted children compared to a baseline of 165 million in 2012. Currently, there are: "59 million children that are stunted in Africa, 87 million in Asia, 6 million in Latin America, and the remaining 3 million in Oceania and developed countries."[2]

The prevalence of overweight and obesity is rapidly growing particularly in low- and middle-income countries, with a small difference between the richest and poorest in most countries. It is believed that most overweight children under 5 live in low- and middle-income countries, and the increase in overweight prevalence extends to adults, with maternal overweight reaching more than 80 percent in some high-burden countries.[2]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, wasting (low weight for height)—which is a manifestation of acute malnutrition—is spiking in 2020.[28]: 25

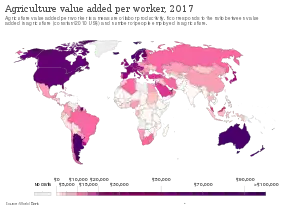

Target 2.3: Double the productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers

The full title for Target 2.3: "By 2030 double the agricultural productivity and the incomes of small-scale food producers, particularly women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets, and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment".[23]

It has two indicators:[26]

- Indicator 2.3.1: The volume of production per labour unit by classes of farming/pastoral/forestry enterprise size.

- Indicator 2.3.2: Average income of small-scale food producers, by sex and indigenous status.[26]

Small-scale producers have is systematically lower production than larger food producers. In most countries, small-scale food producers earn less than half those of larger food producers. It is too early to determine the progress done on this SDG.[30] According to statistics division of the department of Economic and Social Affairs at the UN, the share of small-scale producers among all food producers in Africa, Asia and Latin America ranges from 40% to 85%.[8]

The price of goods is an important indicator of the balance between agricultural production and market demand. It has a strong impact on food affordability and income. Food prices influence consumer affordability and the income of farmers and producers. In low-to-middle income countries in particular, most of the population is employed in agriculture.[31]

This target connects to Sustainable Development Goal 5 (Gender Equality). According to National Geographic, the pay gap between men and women in the agriculture field averages at 20-30%.[32] When the incomes of small-scale food producers are not affected by whether the farmer is female or where they are from, farmers will be able to increase their financial stability. Being more financially stable means doubling the productivity of food. Closing the gender gap could feed 130 million people out of the 870 million undernourished people in the world. Gender equality in agriculture is essential to helping achieve zero hunger.

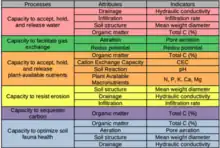

Target 2.4: Sustainable food production and resilient agricultural practices

The full title for Target 2.4: "By 2030 ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters, and that progressively improve land and soil quality".[23]

This target has one indicator:

- Indicator 2.4.1: Proportion of agricultural area under productive and sustainable agriculture".[26]

"Sustainable agriculture is at the heart of the 2030 Agenda". This indicator is purely dedicated to addressing issues related to agriculture.

A farm was considered unsustainable if the soil is bad and the water is not well managed. However, in recent years, there has been a realization that sustainability is far beyond this. It includes economic and social dimensions, as well as putting the farmer at the centre. A farm can no longer be labelled as sustainable if it is not economically well and resilient to external factors, or if the well-being of the farmers and everyone working at the farm is put at stake.[33]

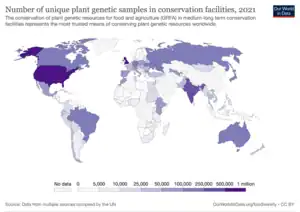

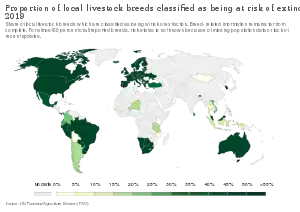

Target 2.5: Maintain the genetic diversity in food production

The full title for Target 2.5: "By 2020 maintain genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants, farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at national, regional and international levels, and ensure access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge as internationally agreed."[23]

It has two indicators:[26]

- Indicator 2.5.1: Number of plant and animal genetic resources for food and agriculture secured in either medium or long-term conservation facilities.

- Indicator 2.5.2: Proportion of local breeds classified as being at risk, not-at-risk or at the unknown level of risk of extinction.

The FAO's Gene Bank Standards for Plant Genetic Resources is the entity that sets the benchmark for scientific and technical best practices.[34]

Biodiversity is key to food security and nutrition, and to ensuring sustainable increases in agricultural production.

In the case of extinction, only less than 1% of local breeds across the world have enough genetic material stored that would allow us to reconstitute the breed. There has been no progress in conserving animal genetic resources or even efforts to preserve these resources. The increasingly rapid environmental and social changes are causing threats to the diversity of both plant and animal genetic resources.[30]

This target is set for the year 2020, unlike most SDGs which have a target date of 2030.

FAO makes sure the progress of each indicator under Target 5.1 is being met within the stated year of actualization.[35]

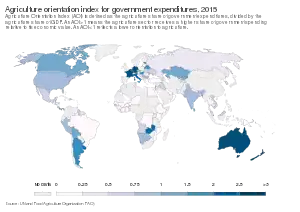

Target 2.a: Invest in rural infrastructure, agricultural research, technology and gene banks

The full title for Target 2.a: "increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development, and plant and livestock gene banks to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular in the least developed countries".[23]

It has two indicators:[26]

- Indicator 2.a.1: Agriculture orientation index for government expenditures.

- Indicator 2.a.2: Total official flows (official development assistance plus other official flows) to the agriculture sector.

Agriculture can be an engine for sustainable development, consequently achieving SGDs.[2] The "Agriculture Orientation Index" (AOI) for Government Expenditures compares the central government contribution to agriculture with the sector's contribution to GDP. An AOI larger than 1 means the agriculture section receives a higher share of government spending relative to its economic value. An AOI smaller than 1 reflects a lower orientation to agriculture.[25]

The high risk faced by agricultural producers often requires the intervention of the government when it comes to redistribution to support smallholders in distress after crop failures and livestock loss from pests, droughts, floods, infrastructure failure, or severe price changes.

To break the vicious cycle of extreme poverty, undernourishment, and malnutrition, it is essential to accelerate growth in the agricultural economy. Economic development and public investment in agriculture are highly correlated. As mentioned in the 2017 High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development thematic review of SDG 2, the parts of the world in extreme poverty and hunger have stagnated values of agricultural capital per worker and public investments in agriculture.[2]

The Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development clearly identifies ODA (Official Development Assistance) and OOFs (Other official flows) as a "relevant element in the financing of sustainable development programmes." Here, "Other official flows (OOF) are transactions by the official sector with countries and territories which do not meet the conditions for eligibility as ODA, either because they are not primarily aimed at development or because they do not meet the minimum grant element requirement."[36]

The agricultural sector is facing several environmental challenges, including changing climate patterns, water shortages, treatment-resistant plagues and increased incidence of natural disasters. There is also an increasing food demand caused by population growth and changing consumer preferences. The challenges and demands could become important threats and risks for food security in many parts of the world. The COVID-19 pandemic could worsen these risks by restricting the mobility of people and products, and disrupting trade and global value chains. During the lockdown, people, products and global value chains had limited mobility. This could lead to scarcity of specific foods and food price increase.[37]

Target 2.b.: Prevent agricultural trade restrictions, market distortions and export subsidies

The full title for Target 2.b: "Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets, including the parallel elimination of all forms of agricultural export subsidies and all export measures with equivalent effect, in accordance with the mandate of the Doha Development Round".[23]

Target 2.b. has two indicators:

- Indicator 2.b.1: Producer Support Estimate".[26] The Producer Support Estimate (PSE) is "an indicator of the annual monetary value of gross transfers from consumers and taxpayers to support agricultural producers, measured at the farm gate level, arising from policy measures, regardless of their nature, objectives or impacts on farm production or income."[38]

- Indicator 2.b.2: Agricultural export subsidies".[26] Export subsidies "increase the share of the exporter in the world market at the cost of others, tend to depress world market prices and may make them more unstable, because decisions on export subsidy levels can be changed unpredictably."[39]

During the 10th Ministerial Conference in Nairobi in December 2015, the World Trade Organization decided to eliminate the export subsidy for agricultural commodities, including export credit, export credit guarantees, or insurance programs for agricultural products.[2] The Doha Round is the latest round of trade negotiations among the WTO membership. It aims to reach major reforms of the international trading system and introduce lower trade barriers and revised trade rules.[40]

Target 2.c. Ensure stable food commodity markets and timely access to information

The full title for Target 2.c is: "adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and their derivatives, and facilitate timely access to market information, including on food reserves, in order to help limit extreme food price volatility".[23]

This target has one indicator: Indicator 2.c.1 is an Indicator of food price anomalies.[26]

Food price anomalies are measured using the domestic food price volatility index. Domestic food price volatility index measures the variation in domestic food prices over time, this is measured as the weighted-average of a basket of commodities based on consumer or market prices. High values indicate a higher volatility in food prices.[25] Extreme food price movements pose a threat to agricultural markets and to the food security and livelihoods, especially of the most vulnerable people.[30]

The G20 Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) offer regular updates on market prices.[2]

Custodian agencies

Custodian agencies are in charge of monitoring the progress of the indicators:[41]

- For all Indicators under Targets 2.1, 2.3 and 2.5, and for Indicators 2.a.1 and 2.c.1: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

- Indicators 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 : United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO)

- Indicator 2.2.3: World Health Organization (WHO)

- For all Indicators under Targets 2.3 and 2.5, and for Indicators 2.a.1 and 2.c.1: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

- Indicator 2.4.1: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

- Indicator 2.a.2: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- Indicator 2.b.1: United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)

Tools

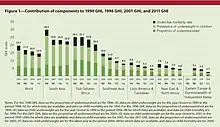

The Global Hunger Index (GHI)

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool designed to measure and track hunger at global, regional, and national levels.

Each year, GHI scores are calculated to track progress and setbacks in fighting hunger. The GHI is designed to raise awareness and understanding of the struggle against hunger. It provides a way to compare levels of hunger between countries and regions. It calls attention to areas of the world where hunger levels are highest and where additional efforts are needed to eliminate hunger.

The FAO Food Price Index (FFPI)

The FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) is a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food commodities.[42] Monitoring of food prices is provided by publicly available sources including food price index (FAO-FPI): monitoring prices monthly, with trends analysed biannually by the Food Outlook publication; reporting on food import bills is provided quarterly by the Crop Prospects and Food Situation publication, and quarterly WFP Global Market Monitor: reporting on price trends of staple commodities in approximately 70 countries and monthly country-specific market bulletins.

The GIEWS Food Price Monitoring and Analysis (FPMA) provides an analysis of domestic price trends of basic foods at global level and latest food market policy developments as well as early warnings on exceptionally high food prices at the country level that may negatively affect food security.[2]

Overall progress and challenges

Despite the progress, research shows that more than 790 million people worldwide still suffer from hunger. There has been major progress in the fight against hunger over the last 15 years.[43] In 2017, during a side event at the High-Level Political Forum under the theme of "Accelerating progress towards achieving SDG 2: Lessons from national implementation", a series of recommendations and actions were discussed. Stakeholders like the French UN mission, Action Against Hunger, Save The Children and Global Citizen were steering the conversation. It is unlikely there will be an end to malnutrition on the African continent by 2030.[12]

To achieve progress towards SDG 2 the world needs to build political will and country ownership. It also needs to improve the narrative around nutrition to make sure that it is well understood by political leaders and address gender inequality, geographic inequality and absolute poverty. It also calls for concrete actions including working at sub-national levels, increasing nutrition funding and ensuring they target the first 1000 days of life and going beyond actions that address only the immediate causes of malnutrition and look at the drivers of under-nutrition, as well as at the food system as a whole.[44]

2019 data for world hunger is shown in the WFP Hunger Map.[45]

The SDG 2 targets ignore the importance of value chains and food systems. Among the targets of SDG 2 are micronutrient and macronutrient deficiencies, but not overconsumption or the consumption of foods high in salt, fat, and sugars, ignoring the health problems associated with such diets; The SDG 2 targets propose a doubling of agricultural productivity and incomes for the small-scale farmer, but ignoring that also larger-scale farmers can earn relatively low incomes from farming; It calls sustainable agriculture without clarifying what sustainable agriculture entails exactly. A substantial number of indicators currently used for SDGs monitoring are not specifically developed for the SDGs, so the information needed for SDGs monitoring is not necessarily available and is not appropriate to reflect the interconnected nature of the SDG. The lack of connected or coordinated action from food production to consumption at all levels hinders progress on SDG 2.[46]

In 2021, the first review of the food security aspects of SDG 2 was conducted in Melanesia. Review and research findings suggest that Pacific Small island developing States (PSIDS) are facing a "global syndemic" of the trinity of obesity, malnutrition, and climate change. While SDG 2 has made progress in reducing stunting and wasting, considerable efforts are still needed to reverse the rising incidence of non-communicable diseases and achieve food security in PSIDS. In the case of Melanesians, the shift from traditional diets to nutrition is accelerating global malnutrition, over-rapid urbanization, lifestyle changes, imported food, and deforestation are destroying traditional agricultural biodiversity and knowledge of food systems. The review shows that SDG 2's future strategies should focus on promoting the link between agriculture, nutrition, and health.[47]

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The achievement of SDG 2 has been jeopardized by a number of factors, the most serious of which happened in 2019, 2020 and 2021; with the unprecedented 2019–2021 locust infestation in Eastern Africa and the 2020 global COVID-19 pandemic. The Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) has noted that trends in food insecurity, disruption in food supply, and income contribute to "increasing the risk of child malnutrition, as food insecurity affects diet quality, including the quality of children's and women's diets, and people's health in different ways".[10]

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown has placed a huge amount of pressure on agricultural production, disrupted global value and supply chain. Subsequently, this raises issues of malnutrition and inadequate food supply to households, with the poorest of them all gravely affected.[48] This has caused more than 132 million people to suffer from undernourishment in 2020.[49] According to recent research there could be a 14% increase in the prevalence of moderate or severe wasting among children younger than five years due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[50]

Supply of agricultural materials: During covid-19, the transportation was blocked and the supply of agricultural materials was tight. Agricultural departments at all levels successively issued a series of policies to ensure the normal transportation of downstream agricultural materials.

New challenges brought by the pandemic: The novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic has spread worldwide and will cause interference to the international grain market.[51] Food costs have been at an all-time high on the international market since December 2019. The food price index released by FAO in January 2020 increased by 2.8% month to month, reaching the highest value since May 2018. [52] To deal with grain crises caused by various public emergencies and natural disasters, we need a robust grain reserve regulating system and emergency management mechanism.[53]

The development of agricultural intelligence has been sparked by Covid-19. The most significant difficulty that Covid-19 has posed to the grain planting and processing industry is a labor shortage. Farmers with automated production and artificial intelligence technologies, on the other hand, have a greater edge in this pandemic and a better ability to respond to emergencies. In the future, smart agriculture will become a growing trend.

New Technologies

To address the increasing challenge of attaining the SDG 2 goal of Zero Hunger, new research has emerged on some of the new technologies that can be implemented to increase agricultural productivity and address the issues of climate change. Climate change is likely to continue slowing the estimated reductions in hunger, especially in the coming decades, increasing the amount of people that are at the risk of hunger to over 16 million by 2030.[54] To mitigate the negative consequences of climate change, increasing investment in agricultural technology is required to enhance agricultural productivity. Furthermore, increased agricultural R&D will lower the prevalence of hunger among 55 million people in Africa.[54] When agricultural intensification is needed, increased investment in capital technology is required to increase the overall productivity while minimizing the carbon footprint of farming.[55] Advancing technology, such as robots and mechanization, is one of the many economic benefits.[55] At the same time, pay attention to the following points: 1. Water efficiency - water conservation and pollution. 2. Switch to sustainable materials. An increase in new technology investment will have a substantial influence on solving climate change concerns and reaching the SDG 2 goal of Zero Hunger.

It has been recommended that the use of carbon smart technologies should be used to improve the chemical and physical qualities of soil, which can aid in mitigating GHG emissions and increase crop yields.[56] Crop residue retention, tillage, agroforestry, land use management systems, biofuels, and integrated nutrient management are some of the Carbon Smart Technologies advised.[56] USA-Based Remote-Sensing Imagery has also been looked at to support SDG 2. As increases of small mammals pose a threat to crop production, the technology seeks to create a balance in the ecosystem.[57] As a result, new advancements such as unmanned aerial systems (UAS) will have a substantial impact on the commercial and scientific applications of remote sensing. There has also been research into the use of Clustered regular interspace short palindromic repeats-associated protein (CRSPR-Cas) technology. It can be utilized to improve food crops and aid in the development of future crops in order to assist in the eradication of global hunger.[58]

It is critical that new agricultural technologies improve sustainability to reduce the impact that agriculture has on the environment. In order to handle the mounting issues of climate change the new tech should be able to provide sustainable solutions, which can assist in the achievement of SDG 2's zero hunger goal.

Shift to Annual-based Agriculture

The ongoing effort to enhance food production has put a major strain on world soil resources. Tillage, the absence of continuous year-round plant cover, the lack of continuous deep root systems and crop functional variety, and inadequate nutrient budgets have all contributed to soil degradation.[59] In order to support high yielding food production, the use of degraded land for agricultural production is used, employing this type of land demands ever increasing management interventions. Management interventions used often exacerbate land degradation by increasing soil carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) losses.[59] Perennialization, or the use of perennial crops and forages in extended cycles, has been viewed as a critical strategy for maintaining present and future crop yields needed to feed the world's population.[59]

Perennialization can help with soil fertility restoration, soil carbon sequestration, nitrogen (N) availability, and phosphorus (P) retention, all of which are important parts of ecological nutrient management.[59] Traditional farming methods commonly result in soil organic carbon loss. Perennialization may also help with climate mitigation methods by promoting high-aggregation soils that are more equipped to withstand large precipitation events. Perennials are an important part of sustainable soil management and can assist in achieving the goal of zero hunger.[59]

Importance of Fisheries

Inland fish provide food and livelihoods for billions of people throughout the world, and they are critical to the proper functioning of freshwater ecosystems. However, these services are noticeably absent from development talks and initiatives, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[60]

Inland fisheries are small-scale, subsistence-based fisheries that are caught and consumed locally.[61] In the developing world, fishes are a valuable source of protein, as well as micronutrients. Inland native fishes are particularly important as a source of protein as other sources are either unavailable or too expensive, and hence are rarely consumed.[61] Essential micronutrients such as vitamins D and B, minerals (calcium, phosphorus, iodine, zinc, iron, and selenium) and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) are highly bioavailable and found in abundance in fish.[62]

There are subpopulations in Africa, South America, and Asia that are disproportionately reliant on inland fisheries.[63] Recent study found that diet variety scores would decline from three to two if fish were eliminated from meals [diets in Sub-Saharan African children], increasing the risk of micronutrient deficiencies. As a result, it's critical that policies protect the present supply of nutrient-dense fish for the children who rely on fish for their diet quality.[64]

The significance of inland fisheries to global food security is currently underestimated due to insufficient evaluation and data availability. Inland fisheries have been overlooked in favor of other benefits that freshwater can provide, such as: electricity, municipal use, and agricultural irrigation. Inland fisheries are commonly underrepresented or ignored in national and municipal water development decision-making processes as a result.[61]

As a result, if we are to achieve the goal of zero hunger, we must recognize the importance inland fisheries have on global nutrition.

GM crops

The rapid growth of the world population requires the development of new technologies to feed people adequately; even now, an eighth of the world's people go to bed hungry. The genetic modification of food plants can help meet part of this challenge.[65] In the mid-1990s, genome breeding methods and transformation techniques modified by mutation and transgene improved plant traits and produced high-yielding crop varieties. The CRISPR-CAS technology has helped improve the quality and efficiency of crop varieties through improved photosynthesis to achieve zero hunger and overcome malnutrition in a short period of time. Traditional crop domestication is a long process, but CRISPR's MGE system can significantly speed up that process. In addition to major food crops, orphan crops, such as millet (Panicum miliaceum), pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), cassava (Manihot esculenta), yam (Dioscorea sp.), etc., can also be easily modified through MGE systems to boost the food supply.[66]

We know that iron deficiency is a global problem and that second-best zinc supplements are more common than previously thought. A number of programmes have been developed to prevent and treat iron and zinc deficiency, ranging from the supplement and fortification of common staple foods to changes in traditional food preparation methods, where genetic modification of plants to improve micronutrient nutrition is a complementary approach. Increasing the micronutrient content of conventional crops and/or increasing the bioavailability of iron and zinc in such crops can improve the micronutrient nutrition of the population eating these crops. Beta-carotene enhances iron absorption in humans and has a direct stimulating effect on iron uptake by cells. One of the most famous iron absorption promoters is ascorbic acid. Increased ascorbic acid in the diet results in a significant increase in iron absorption in the body. Therefore, the overexpression of ascorbic acid in plants may positively affect human iron nutrition. For example, Golden Rice is a genetically modified Rice variety developed with the help of Syngenta, an American seed company. The edible part of the endosperm of rice has been genetically engineered to contain beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A. Beta-carotene is converted into vitamin A in the body and can alleviate vitamin A deficiency. The carotene gives the rice its golden colour, hence the name "golden rice".[67]

Future of agriculture: The global population continues to grow and will surpass 9.5 billion by 2050. Demand for food is expected to double by 2050. If we do not use genetically modified crops we will have to use more land for farming, We need an additional 120 million acres to maintain the status quo.[68] That's roughly the size of California. This pressure on land for agriculture means more wetlands will be drained, and an increase in deforestation. We need more land to feed our diet. As a result, we need to realize the importance of GM crops to achieve zero hunger.

Links with other SDGs

The SDGs are deeply interconnected. All goals could be affected if progress on one specific goal is not achieved.

Climate change and natural disasters are affecting food security. Disaster risk management, climate change adaptation and mitigation are essential to increase harvests quality and quantity. Targets 2.4 and 2.5 are directly linked to the environment.[69]

Reducing hunger can directly help in advancing Goals SDG 1, SDG 3 and SDG 8 by increasing rural and developing country incomes and access to nutrition. Since a significant number of farmers, especially in Africa and Asia, are women, advancing SDG 2 can also impact SDG 5, gender equality. Hunger and Agriculture are also linked to SDG 6 (when dealing with water scarcity and pollution), SDG 13 (when discussing greenhouse gas emissions) and SDG 15 (since it is linked to soil degradation).

Organizations and programmes

Organizations, programmes and funds that have been set up to tackle hunger and therefore also SDG 2 include:

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO): FAO was established as a specialized agency of the United Nations in 1945. One of FAO's strategic objectives is to help eliminate hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition.

- World Food Programme (WFP): Founded in 1963, WFP is the lead UN agency that responds to food emergencies and has programmes to combat hunger worldwide. Reports of the WFP of its Executive Board and on its annual performance are linked above under ECOSOC.

- International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD): Founded in 1977, IFAD focuses on rural poverty reduction, working with poor rural populations in developing countries to eliminate poverty, hunger, and malnutrition.

- World Bank: Founded in 1944, the World Bank is actively involved in funding food projects and programmes.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): UNEP was established in 1972 as the international arm providing guidance and governance to environmental issues. One of the topics that UNEP addresses currently is food security.

International NGOs include:

- Action Against Hunger (or Action Contre La Faim (ACF) in French) is a global humanitarian organization which originated in France and is committed to ending world hunger. The organization helps malnourished children and provides communities with access to safe water and sustainable solutions to hunger.

- Feeding America is a United States–based nonprofit organization that is a nationwide network of more than 200 food banks that feed more than 46 million people through food pantries, soup kitchens, shelters, and other community-based agencies.

- The Hunger Project (THP) is an organization committed to the sustainable end of world hunger. It has ongoing programs in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where it implements programs aimed at mobilizing rural grassroots communities to achieve sustainable progress in health, education, nutrition, and family income.

US-based organizations

In the US there are over 18,000 tax-exempt organizations working on issues related to UN SDG 2, according to data filed with the Internal Revenue Service –IRS and aggregated by X4Impact.[70] X4Impact, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, Ford Foundation,[71] Hewlett Foundation,[72] and Giving Tech Labs, created a free online interactive tool Hunger and Malnutrition in the US. This online tool enables users to see hunger-related indicators nationally and by state, as well as relevant information for over eighteen thousand tax-exempt organizations in the US working on issues related to UN SDG 2. The nonprofit data in the tool is updated every 15 days while the indicators are updated annually.

References

- ↑ United Nations (2015) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "2017 HLPF Thematic review of SDG2" (PDF). High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development.

- ↑ "Goal 2: Zero Hunger". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ mercy corps, global hunger facts (18 March 2015). "Global hunger facts".

- 1 2 United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ↑ CIRAD, food systems (28 April 2021). "Food systems at risk: trends and challenges".

- ↑ "sustainability".

- 1 2 "SDG Indicators". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ "The sustainable development goals report 2020" (PDF).

- 1 2 Document card | FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. www.fao.org. 2020. doi:10.4060/ca9692en. ISBN 978-92-5-132901-6. S2CID 239729231. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- 1 2 FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2018. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Rome, FAO

- 1 2 Osgood-Zimmerman, Aaron; Millear, Anoushka I.; Stubbs, Rebecca W.; Shields, Chloe; Pickering, Brandon V.; Earl, Lucas; Graetz, Nicholas; Kinyoki, Damaris K.; Ray, Sarah E.; Bhatt, Samir; Browne, Annie J. (2018-03-01). "Mapping child growth failure in Africa between 2000 and 2015". Nature. 555 (7694): 41–47. Bibcode:2018Natur.555...41O. doi:10.1038/nature25760. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 6346257. PMID 29493591.

- ↑ Kinyoki, D.; et al. (8 January 2020). "Mapping child growth failure across low- and middle-income countries". Nature. 577 (7789): 231–234. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..231L. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1878-8. PMC 7015855. PMID 31915393.

- 1 2 "#Envision2030: 17 goals to transform the world for persons with disabilities- United Nations Enable". www.un.org. 9 February 2016. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ United Nations Economic and Social Council (2020) Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Report of the Secretary-General, High-level political forum on sustainable development, convened under the auspices of the Economic and Social Council (E/2020/57), 28 April 2020

- 1 2 "Progress for Every Child in the SDG Era" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ "Goal 2: Zero hunger". UNDP. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ "Goal 2: Zero hunger". The Global Goals. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ↑ knowledge platform, food security. "food security and nutrition and sustainable agriculture".

- 1 2 Fan, Shenggen and Polman, Paul. 2014. An ambitious development goal: Ending hunger and undernutrition by 2025. In 2013 Global food policy report. Eds. Marble, Andrew and Fritschel, Heidi. Chapter 2. Pp 15-28. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- ↑ "Risk of hunger pandemic as coronavirus set to almost double acute hunger by end of 2020". WFP. 16 April 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Goal 2: Zero Hunger". UN. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- 1 2 "SDG Tracker". Our World in Data.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Goal 2: Zero Hunger - SDG Tracker". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Goal 2 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". sdgs.un.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- 1 2 Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah (2013-10-08). "Hunger and Undernourishment". Our World in Data.

- 1 2 BMGF (2020) Covid-19 A Global Perspective - 2020 Goalkeepers Report, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, USA

- ↑ World Health Organization (2014). WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Stunting Policy Brief.

- 1 2 3 "SDG Progress report". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah (2013-10-08). "Food Prices". Our World in Data.

- ↑ "Revealing the Gap Between Men and Women Farmers - National Geographic | Nat Geo Food". History. 2014-03-07. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ "2.4.1 Agricultural sustainability - Sustainable Development Goals - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ "Indicator 2.5.1 - E-Handbook on SDG Indicators - UN Statistics Wiki". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ ""United Nations (2018) Economic and Social Council, Conference of European Statisticians, Geneva," (PDF). United Nations, Geneva" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ↑ "DAC Glossary of Key Terms and Concepts - OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ FAO. 2017. The future of food and agriculture – trends and challenges. Rome.

- ↑ "OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms - Producer Support Estimate (PSE) Definition". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ "Multilateral Trade Negotiations on Agriculture: A Resource Manual - Agreement on Agriculture - Export Subsidies". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ "WTO | The Doha Round". www.wto.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ ""United Nations (2018) Economic and Social Council, Conference of European Statisticians, Geneva," (PDF). United Nations, Geneva" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ↑ "FAO Food Price Index - World Food Situation - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ "Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture — SDG Indicators". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ "2018 Global Nutrition Report by UNICEF". United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ↑ WFP (2019) Hunger map 2019, World Food Program.

- ↑ Veldhuizena, Linda JL; Gillera, Ken E.; Oosterveerb, Peter; Brouwerc, Inge D.; Janssend, Sander; van Zantene, Hannah HE.; Slingerlanda, M.A. (2020). "The Missing Middle: Connected action on agriculture and nutrition across global, national and local levels to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 2". Global Food Security. 24: 100336. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2019.100336. S2CID 211792782.

- ↑ Vogliano, Chiris; Murray, Linda; Coad, Jane; Wham, Caril; Maelaua, Josephine; Kafa, Rosemary; Burlingame, Barbara (2021). "Progress towards SDG 2: Zero hunger in melanesia – A state of data scoping review". Global Food Security. 29: 100519. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100519. S2CID 233582750.

- ↑ Gulseven, Osman; Al Harmoodi, Fatima; Al Falasi, Majid; ALshomali, Ibrahim (2020). "How the COVID-19 Pandemic Will Affect the UN Sustainable Development Goals?". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3592933. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 225914413.

- ↑ "UN/DESA Policy Brief #81: Impact of COVID-19 on SDG progress: a statistical perspective | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". www.un.org. 2020-08-27. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ↑ The lancet, Impacts of covid-19 (2020). "Impacts of covid 19 on childhood malnutrition and nutrition related mortality". The Lancet. 396 (10250): 519–521. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31647-0. PMC 7384798. PMID 32730743.

- ↑ Agricultural Supply Chains during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A study of market arrivals of seven key food commodities in India – IDEAs. (2020, April 22). Retrieved December 17, 2021, from Networkideas.org website: https://www.networkideas.org/featured-themes/2020/04/agricultural-supply-chains-during-the-covid-19-lock-down-a-study-of-market-arrivals-of-seven-key-food-commodities-in-india/

- ↑ Pu, M., & Zhong, Y. (2020). Rising concerns over agricultural production as COVID-19 spreads: Lessons from China. Global Food Security, 26, 100409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100409

- ↑ Rivera-Ferre, M. G., López-i-Gelats, F., Ravera, F., Oteros-Rozas, E., di Masso, M., Binimelis, R., & El Bilali, H. (2021). The two-way relationship between food systems and the COVID19 pandemic: causes and consequences. Agricultural Systems, 191, 103134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103134.

- 1 2 Mason-D'Croz, Daniel; Sulser, Timothy B.; Wiebe, Keith; Rosegrant, Mark W.; Lowder, Sarah K.; Nin-Pratt, Alejandro; Willenbockel, Dirk; Robinson, Sherman; Zhu, Tingju; Cenacchi, Nicola; Dunston, Shahnila (2019-04-01). "Agricultural investments and hunger in Africa modeling potential contributions to SDG2 – Zero Hunger". World Development. 116: 38–53. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.12.006. ISSN 0305-750X. PMC 6358118. PMID 30944503.

- 1 2 Giller, Ken E.; Delaune, Thomas; Silva, João Vasco; Descheemaeker, Katrien; van de Ven, Gerrie; Schut, Antonius G.T.; van Wijk, Mark; Hammond, James; Hochman, Zvi; Taulya, Godfrey; Chikowo, Regis (2021-10-01). "The future of farming: Who will produce our food?". Food Security. 13 (5): 1073–1099. doi:10.1007/s12571-021-01184-6. ISSN 1876-4525. S2CID 239704592.

- 1 2 Yeboah, Stephen; Owusu Danquah, Eric; Oteng-Darko, Patricia; Agyeman, Kennedy; Tetteh, Erasmus Narteh (2021-08-26). "Carbon Smart Strategies for Enhanced Food System Resilience Under a Changing Climate". Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 5: 715814. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2021.715814. ISSN 2571-581X.

- ↑ Ezzy, Haitham; Charter, Motti; Bonfante, Antonello; Brook, Anna (January 2021). "How the Small Object Detection via Machine Learning and UAS-Based Remote-Sensing Imagery Can Support the Achievement of SDG2: A Case Study of Vole Burrows". Remote Sensing. 13 (16): 3191. Bibcode:2021RemS...13.3191E. doi:10.3390/rs13163191.

- ↑ Ahmad, Shakeel; Tang, Liqun; Shahzad, Rahil; Mawia, Amos Musyoki; Rao, Gundra Sivakrishna; Jamil, Shakra; Wei, Chen; Sheng, Zhonghua; Shao, Gaoneng; Wei, Xiangjin; Hu, Peisong (2021-08-04). "CRISPR-Based Crop Improvements: A Way Forward to Achieve Zero Hunger". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 69 (30): 8307–8323. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c02653. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 34288688. S2CID 236173991.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mosier, Samantha; Córdova, S. Carolina; Robertson, G. Philip (2021-10-11). "Restoring Soil Fertility on Degraded Lands to Meet Food, Fuel, and Climate Security Needs via Perennialization". Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 5: 706142. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2021.706142. ISSN 2571-581X.

- ↑ Lynch, Abigail J.; Elliott, Vittoria; Phang, Sui C.; Claussen, Julie E.; Harrison, Ian; Murchie, Karen J.; Steel, E. Ashley; Stokes, Gretchen L. (August 2020). "Inland fish and fisheries integral to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals". Nature Sustainability. 3 (8): 579–587. doi:10.1038/s41893-020-0517-6. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 216459224.

- 1 2 3 Youn, So-Jung; Taylor, William W.; Lynch, Abigail J.; Cowx, Ian G.; Douglas Beard, T.; Bartley, Devin; Wu, Felicia (2014-11-01). "Inland capture fishery contributions to global food security and threats to their future". Global Food Security. SI: GFS Conference 2013. 3 (3–4): 142–148. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2014.09.005. ISSN 2211-9124.

- ↑ Béné, Christophe; Arthur, Robert; Norbury, Hannah; Allison, Edward H.; Beveridge, Malcolm; Bush, Simon; Campling, Liam; Leschen, Will; Little, David; Squires, Dale; Thilsted, Shakuntala H. (2016-03-01). "Contribution of Fisheries and Aquaculture to Food Security and Poverty Reduction: Assessing the Current Evidence". World Development. 79: 177–196. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.007. ISSN 0305-750X.

- ↑ Funge‐Smith, Simon; Bennett, Abigail (2019-09-26). "A fresh look at inland fisheries and their role in food security and livelihoods". Fish and Fisheries. 20 (6): 1176–1195. doi:10.1111/faf.12403. ISSN 1467-2960. S2CID 204163422.

- ↑ O'Meara, Lydia; Cohen, Philippa J.; Simmance, Fiona; Marinda, Pamela; Nagoli, Joseph; Teoh, Shwu Jiau; Funge-Smith, Simon; Mills, David J.; Thilsted, Shakuntala H.; Byrd, Kendra A. (2021-03-01). "Inland fisheries critical for the diet quality of young children in sub-Saharan Africa". Global Food Security. 28: 100483. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100483. ISSN 2211-9124. S2CID 233849427.

- ↑ National Geographic Society. (2020, January 28). Are Genetically Modified Crops the Answer to World Hunger? Retrieved December 16, 2021, from National Geographic Society website: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/are-genetically-modified-crops-answer-world-hunger/

- ↑ Scopus - CRISPR-Based Crop Improvements: A Way Forward to Achieve Zero Hunger. (2021). Retrieved December 16, 2021, from Scopus.com website: https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85112365915&origin=resultslist&sort=plf-f&src=s&st1=sdg2&nlo=&nlr=&nls=&sid=3c314d03d63a224e3e9634a1eab3f6bb&sot=b&sdt=sisr&sl=19&s=TITLE-ABS-KEY%28sdg2%29&ref=%28genetically+modified%29&relpos=0&citeCnt=4&searchTerm=

- ↑ LönnerdalB. (2003). Genetically Modified Plants for Improved Trace Element Nutrition. The Journal of Nutrition, 133(5), 1490S1493S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.5.1490s

- ↑ Global Demand for Food Is Rising. Can We Meet It? (2016, April 7). Retrieved December 16, 2021, from Harvard Business Review website: https://hbr.org/2016/04/global-demand-for-food-is-rising-can-we-meet-it

- ↑ Environment, U. N. (2017-10-02). "GOAL 2: Zero hunger". UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ↑ "Press Release: X4Impact, a Market Intelligence Platform for Social Innovation, Announced U.S. Launch During the 2020 Un General Assembly - NextBillion". nextbillion.net. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ X4Impact. "Ford Foundation Fuels Tech for the Public Interest with X4Impact". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ "Press Release: Hewlett Foundation Becomes X4Impact Founding Partner to Advance Technology for the Public Interest With Focus on Entrepreneurs Creating Tech for Good Solutions - NextBillion". nextbillion.net. Retrieved 2021-11-15.