Tarsal tunnel syndrome

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Posterior tibial nerve neuralgia | |

| |

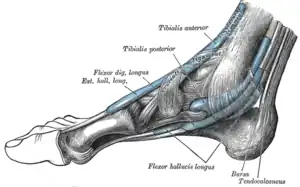

| The mucous sheaths of the tendons around the ankle. Medial aspect. | |

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is a compression neuropathy and painful foot condition in which the tibial nerve is compressed as it travels through the tarsal tunnel.[1] This tunnel is found along the inner leg behind the medial malleolus (bump on the inside of the ankle). The posterior tibial artery, tibial nerve, and tendons of the tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus muscles travel in a bundle through the tarsal tunnel. Inside the tunnel, the nerve splits into three segments. One nerve (calcaneal) continues to the heel, the other two (medial and lateral plantar nerves) continue on to the bottom of the foot. The tarsal tunnel is delineated by bone on the inside and the flexor retinaculum on the outside.

Patients with TTS typically complain of numbness in the foot radiating to the big toe and the first three toes, pain, burning, electrical sensations, and tingling over the base of the foot and the heel.[1] Depending on the area of entrapment, other areas can be affected. If the entrapment is high, the entire foot can be affected as varying branches of the tibial nerve can become involved. Ankle pain is also present in patients who have high level entrapments. Inflammation or swelling can occur within this tunnel for a number of reasons. The flexor retinaculum has a limited ability to stretch, so increased pressure will eventually cause compression on the nerve within the tunnel. As pressure increases on the nerves, the blood flow decreases.[1] Nerves respond with altered sensations like tingling and numbness. Fluid collects in the foot when standing and walking and this makes the condition worse. As small muscles lose their nerve supply they can create a cramping feeling.

Symptoms and signs

Some of the symptoms are:

- Pain and tingling in and around ankles and sometimes the toes

- Swelling of the feet and ankle area.

- Painful burning, tingling, or numb sensations in the lower legs. Pain worsens and spreads after standing for long periods; pain is worse with activity and is relieved by rest.

- Electric shock sensations

- Pain radiating up into the leg,[1] behind the shin, and down into the arch, heel, and toes

- Hot and cold sensations in the feet

- A feeling as though the feet do not have enough padding

- Pain while operating automobiles

- Pain along the posterior tibial nerve path

- Burning sensation on the bottom of foot that radiates upward reaching the knee

- "Pins and needles"-type feeling and increased sensation on the feet

- A positive Tinel's sign[1]

Tinel's sign is a tingling electric shock sensation that occurs when you tap over an affected nerve. The sensation usually travels into the foot but can also travel up the inner leg as well.

Causes

3D still showing tarsal tunnel syndrome

3D still showing tarsal tunnel syndrome This is an image of a normal arched foot.

This is an image of a normal arched foot..jpg.webp) When comparing to the normal arch image, this image of fallen arches helps create a visualization of how the tibial nerve can be strained and compressed due to the curvature.

When comparing to the normal arch image, this image of fallen arches helps create a visualization of how the tibial nerve can be strained and compressed due to the curvature. Increased pressure and high loads on the ankle joint can cause TTS, as can smaller than normal shoes. In this picture, most of the load is placed upon the knee and ankle joint.

Increased pressure and high loads on the ankle joint can cause TTS, as can smaller than normal shoes. In this picture, most of the load is placed upon the knee and ankle joint.

It is difficult to determine the exact cause of tarsal tunnel syndrome. It is important to attempt to determine the source of the problem. Treatment and the potential outcome of the treatment may depend on the cause. Anything that creates pressure in the tarsal tunnel can cause TTS. This would include benign tumors or cysts, bone spurs, inflammation of the tendon sheath, nerve ganglions, or swelling from a broken or sprained ankle. Varicose veins (that may or may not be visible) can also cause compression of the nerve. TTS is more common in athletes and other active people. These people put more stress on the tarsal tunnel area. Flat feet may cause an increase in pressure in the tunnel region and this can cause nerve compression. Those with lower back problems may have symptoms. Back problems with the L4, L5 and S1 regions are suspect and might suggest a "Double Crush" issue: one "crush" (nerve pinch or entrapment) in the lower back, and the second in the tunnel area. In some cases, TTS can simply be idiopathic.[1]

Rheumatoid Arthritis has also been associated with TTS.[2]

Neurofibromatosis can also cause TTS. This is a disease that results in the formation of pigmented, cutaneous neurofibromas. These masses, in a specific case, were shown to have the ability to invade the tarsal tunnel causing pressure, therefore resulting in TTS.[3]

Diabetes makes the peripheral nerve susceptible to nerve compression, as part of the double crush hypothesis.[4] In contrast to carpal tunnel syndrome due to one tunnel at the wrist for the median nerve, there are four tunnels in the medial ankle for tarsal tunnels syndrome.[5] If there is a positive Tinel sign when you tap over the inside of the ankle, such that tingling is felt into the foot, then there is an 80% chance that decompressing the tarsal tunnel will relieve the symptoms of pain and numbness in a diabetic with tarsal tunnel syndrome.[6]

Risk factors

Anything compromising the tunnel of the posterior tibial nerve proves significant in the risk of causing TTS. Neuropathy can occur in the lower limb through many modalities, some of which include obesity and inflammation around the joints. By association, this includes risk factors such as RA, compressed shoes, pregnancy, diabetes and thyroid diseases[7]

Athletic activities

The athletic population tends to put themselves at greater risk of TTS due to the participation in sports that involve the lower extremities. Strenuous activities involved in athletic activities put extra strain on the ankle and therefore can lead to the compression of the tibial nerve.[8]

Activities that especially involve sprinting and jumping have a greater risk of developing TTS. This is due to the ankle being put in eversion, inversion, and plantarflexion at high velocities. Examples of sports that can lead to TTS include basketball, track, soccer, lacrosse, snowboarding, and volleyball.[9] Participation in these sports should be done cautiously due to the high risk of developing TTS. However athletes will tend to continue to participate in these activities therefore proper stretching, especially in lower extremities, prior to participation can assist in the prevention of developing TTS.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based upon physical examination findings. Patients' pain history and a positive Tinel's sign are the first steps in evaluating the possibility of tarsal tunnel syndrome. X-ray can rule out fracture. MRI can assess for space occupying lesions or other causes of nerve compression. Ultrasound can assess for synovitis or ganglia. Nerve conduction studies alone are not, but they may be used to confirm the suspected clinical diagnosis. Common causes include trauma, varicose veins, neuropathy and space-occupying anomalies within the tarsal tunnel. Tarsal tunnel syndrome is also known to affect both athletes and individuals that stand a lot.[1]

A neurologist or a physiatrist usually administers nerve conduction tests or supervises a trained technologist. During this test, electrodes are placed at various spots along the nerves in the legs and feet. Both sensory and motor nerves are tested at different locations. Electrical impulses are sent through the nerve and the speed and intensity at which they travel is measured. If there is compression in the tunnel, this can be confirmed and pinpointed with this test. Some doctors do not feel that this test is necessarily a reliable way to rule out TTS.[1] Some research indicates that nerve conduction tests will be normal in at least 50% of the cases.

Given the unclear role of electrodiagnostics in the diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome, efforts have been made in the medical literature to determine which nerve conduction studies are most sensitive and specific for tibial mononeuropathy at the level of the tarsal tunnel. An evidence-based practice topic put forth by the professional organization, the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine has determined that Level C, Class III evidence exists for the use of tibial motor nerve conduction studies, medial and lateral plantar mixed nerve conduction studies, and medial and lateral plantar sensory nerve conduction studies. The role of needle electromyography remains less defined.[10]

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is most closely related to carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). However, the commonality to its counterpart is much less or even rare in prevalence[11] Studies have found that patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) show signs of distal limb neuropathy. The posterior tibial nerve serves victim to peripheral neuropathy and often show signs of TTS amongst RA patients. Therefore, TTS is a common discovery found in the autoimmune disorder of rheumatoid arthritis[12]

Prevention

The exact cause of tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) can vary from patient to patient. However the same result is true for all patients, the compression of the posterior tibial nerve and it branches as it travels around the medial malleolus causes pain and irritation for the patient.[13] There are many possible causes for compression of the tibial nerve therefore there are a variety of prevention strategies. One being immobilization, by placing the foot in a neutral position with a brace, pressure is relieved from the tibial nerve thus reducing patients pain.[14][15][16] Eversion, inversion, and plantarflexion all can cause compression of the tibial nerve therefore in the neutral position the tibial nerve is less agitated. Typically this is recommended for the patient to do while sleeping. Another common problem is improper footwear, having shoes deforming the foot due to being too tight can lead to increased pressure on the tibial nerve.[13] Having footwear that tightens the foot for extended periods of time even will lead to TTS. Therefore, by simply having properly fitted shoes TTS can be prevented.

Treatment

Treatments typically include rest, manipulation, strengthening of tibialis anterior, tibialis posterior, peroneus and short toe flexors, casting with a walker boot, corticosteroid and anesthetic injections, hot wax baths, wrapping, compression hose, and orthotics. Medications may include various anti-inflammatories such as Anaprox, or other medications such as Ultracet, Neurontin and Lyrica. Lidocaine patches are also a treatment that helps some patients.

Conservative treatment (nonsurgical)

There are multiple ways that tarsal tunnel can be treated and the pain can be reduced. The initial treatment, whether it be conservative or surgical, depends on the severity of the tarsal tunnel and how much pain the patient is in. There was a study done that treated patients diagnosed with tarsal tunnel syndrome with a conservative approach. Meaning that the program these patients were participated in consisted of physiotherapy exercises and orthopedic shoe inserts in addition to that program. There were fourteen patients that had supplementary tibial nerve mobilization exercises. They were instructed to sit on the edge of a table in a slumped position, have their ankle taken into dorsiflexion and ankle eversion then the knee was extended and flexed to obtain the optimal tibial nerve mobilization. Patients in both groups showed positive progress from both programs.[17] The medial calcaneal, medial plantar and lateral plantar nerve areas all had a reduction in pain after successful nonoperative or conservative treatment.[18] There is also the option of localized steroid or cortisone injection that may reduce the inflammation in the area, therefore relieving pain. Or just a simple reduction in the patient's weight to reduce the pressure in the area.[19]

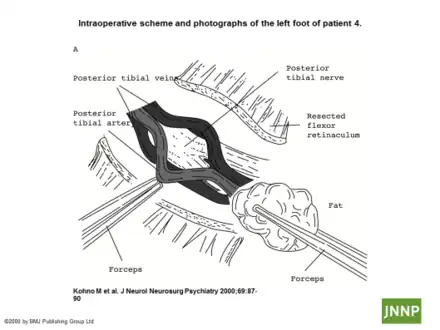

Intraoperative image demonstrating the medial approach and exposure of the flexor hallucis longus tendon

Intraoperative image demonstrating the medial approach and exposure of the flexor hallucis longus tendon Tarsal tunnel release

Tarsal tunnel release

Surgical treatment

If non-invasive treatment measures fail, tarsal tunnel release surgery may be recommended to decompress the area. The incision is made behind the ankle bone and then down towards but not as far as the bottom of foot. The posterior tibial nerve is identified above the ankle. It is separated from the accompanying artery and vein and then followed into the tunnel. The nerves are released. Cysts or other space-occupying problems may be corrected at this time. If there is scarring within the nerve or branches, this is relieved by internal neurolysis. Neurolysis is when the outer layer of nerve wrapping is opened and the scar tissue is removed from within nerve. Following surgery, a large bulky cotton wrapping immobilizes the ankle joint without plaster. The dressing may be removed at the one-week point and sutures at about three weeks.

Complications may include bleeding, infection, and unpredictable healing. The incision may open from swelling. There may be considerable pain and cramping. Regenerating nerve fibers may create shooting pains. Patients may have hot or cold sensations and may feel worse than before surgery. Crutches are usually recommended for the first two weeks, as well as elevation to minimize swelling. The nerve will grow at about one inch per month. One can expect to continue the healing process over the course of about one year.

Many patients report good results. Some, however, experience no improvement or a worsening of symptoms. In the Pfeiffer article (Los Angeles, 1996), fewer than 50% of the patients reported improvement, and there was a 13% complication rate.

Tarsal tunnel can greatly impact patients' quality of life. Depending on the severity, the ability to walk distances people normally take for granted (such as grocery shopping) may become compromised. Proper pain management and counseling is often required.

Results of surgery can be maximized if all four of the medial ankle tunnels are released and you walk with a walker the day after surgery. Success can be improved to 80%.[20]

Incidence

Though TTS is rare, its cause can be determined in 70% of reported cases. In the workplace TTS is considered a musculoskeletal disorder and accounts for 1.8 million cases a year, which accumulates to about $15–$20 billion a year[21] New studies indicate an occurrence of TTS in sports placing high loads on the ankle joint (3). This can be seen in figure 1. TTS occurs more dominantly in active adults, with a higher pervasiveness among women. Active adults that experience more jumping and landing on the ankle joint are more susceptible (see figure 2). Though athletics and sport are correlations, cases are individualistically assessed because of the oddity.

Society and culture

As stated earlier, musculoskeletal disorders can cost up to $15–$20 billion in direct costs or $45–$55 billion in indirect expenses. This is about $135 million a day.[21] Tests that confirm or correct TTS require expensive treatment options like X-rays, CT-scans, MRI and surgery. The three former options for TTS detect and locate, while the latter is a form of treatment to decompress tibial nerve pressure.[22] Since surgery is the most common form of TTS treatment, high financial burden is placed upon those diagnosed with the rare syndrome.

According to South Korea's National Intelligence Service, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un had surgery to correct TTS in his right ankle, the source of a pronounced limp. Kim's disappearance from public for six weeks around the suspected surgery created worldwide speculation about the future of Kim and North Korea.[23]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yates, Ben (2009). Merriman's Assessment of the Lower Limb (3rd ed.). New York: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-08-045107-7.

- ↑ Baylan SP, Paik SW, Barnert AL, Ko KH, Yu J, Persellin RH (1981). "Prevalence of the tarsal tunnel syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis". Rheumatol Rehabil. 20 (3): 148–50. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/20.3.148. PMID 7280489.

- ↑ Mirick, Anika L., Gerald B. Bornstein, and Laura W. Bancroft. "Radiologic Case Study." Orthopedics 36.81 (2013): 154–57. Web. 22 Apr. 2014.

- ↑ Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Seiler WA (1988). "Susceptibility of the diabetic nerve to chronic compression". Ann Plast Surg. 20 (2): 117–119. doi:10.1097/00000637-198802000-00004. PMID 3355055.

- ↑ Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL (1987). "Homologies between the tarsal and carpal tunnels: Implications for treatment of the tarsal tunnel syndrome". Contemp Orthop. 14: 75–79.

- ↑ Lee C, Dellon AL (2004). "Prognostic ability of Tinel sign in determining outcome for decompression surgery decompression surgery in diabetic and non-diabetic neuropathy". Ann Plast Surg. 53 (6): 523–27. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000141379.55618.87. PMID 15602246.

- ↑ Beltran L. S.; Bencardino J.; Ghazikhanian V.; Beltran J. (2010). "Entrapment Neuropathies III: Lower Limb". Seminars in Musculoskeletal Radiology. 14 (5): 501–511. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1268070. PMID 21072728.

- ↑ Kinoshita, M. "Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome in Athletes." American Journal of Sports Medicine 34.8 (2006): 1307–312.

- ↑ Ramani, William, David H. Perrin, and Tim Whiteley. "Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: Case Study of a Male Collegiate Athlete." Journal of Sports Rehabilitation 6 (n.d.): 364-70.

- ↑ "Usefulness of electrodiagnostic techniques in the evaluation of suspected tarsal tunnel syndrome: An evidence-based review". aanem.org/getmedia/51417557-424c-4c29-be6a-5bbaff64517c/TarsalTunnel.pdf.aspx. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ Ahmad, M. M., Tsang, K. K., Mackenney, P. J., & Adedapo, A. O. (2012). Tarsal tunnel syndrome: A literature review. Foot & Ankle Surgery (Elsevier Science), 18(3), 149–152.

- ↑ Baylan, S. P., S. W. Paik, A. L. Barnert, K. H. Ko, J. Yu, and R. H. Persellin. "Prevalence Of The Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome In Rheumatoid Arthritis." Rheumatology 20.3 (1981): 148–150.

- 1 2 Low, Hu L., and George Stephenson. "These Boots Weren't Made for Walking: Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome." Canadian Medical Association Journal 176.10 (2007): 1415–416.

- ↑ Gondring, William H., Elly Trepman, and Byron Shields. "Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: Assessment of Treatment Outcome with an Anatomic Pain Intensity Scale."Foot and Ankle Surgery 15.3 (2009): 133–38.

- ↑ Bracilovic, A., A. Nihal, V. L. Houston, A. C. Beatle, Z. S. Rosenberg, and E. Trepman. "Effect of Foot and Ankle Position on Tarsal Tunnel Compartment Volume." Foot and Ankle International 27.6 (2006): 421–37.

- ↑ Nakasa, Tomoyuki, Kohei Fukuhara, Nobuo Adachi, and Mitsuo Ochi. "Painful Os Intermetatarseum in Athletes: Report of Four Cases and Review of the Literature." Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 127.4 (2007): 261–64. Print.

- ↑ Kavlak Y, Uygur F (2011). "Effects of nerve mobilization exercise as an adjunct to the conservative treatment for patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome". J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 34 (7): 441–8. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.05.017. PMID 21875518.

- ↑ Gondring WH1, Trepman E, Shields B. (2008). Tarsal tunnel syndrome: assessment of treatment outcome with an anatomic pain intensity scale. Foot Ankle Surg. 15(3):133-8

- ↑ Edwards William G.; Lincoln C. Robert; Bassett Frank H.; Goldner J. Leonard (1969). "The Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome Diagnosis and Treatment". JAMA. 207 (4): 716–720. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03150170042009. PMID 4302951.

- ↑ Mullick T, Dellon AL. Results of decompression of four medial ankle tunnels in the treatment of tarsal tunnels syndrome. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2008;24:119–126.

- 1 2 . Jeffress, Charles N. "Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs)." Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs). Occupational Safety & Health Administration, n.d. Web. 11 May 2014.

- ↑ Manasseh, N., Cherian, V., & Abel, L. (2009). Malunited calcaneal fracture fragments causing tarsal tunnel syndrome: A rare cause. Foot & Ankle Surgery (Elsevier Science), 15(4), 207–209.

- ↑ Almasy, KJ Kwon,Steven Almasy,Steve (2014-10-28). "South Korea: Kim Jong Un had ankle surgery to remove cyst". CNN. Archived from the original on 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |