Therapeutic ultrasound

| Therapeutic ultrasound | |

|---|---|

| |

| Application of therapeutic ultrasound in delimited area with neoprene template | |

Therapeutic ultrasound refers generally to any type of ultrasonic procedure that uses ultrasound for therapeutic benefit. Physiotherapeutic ultrasound was introduced into clinical practice in the 1950s, with lithotripsy introduced in the 1980s. Others are at various stages in transitioning from research to clinical use: HIFU, targeted ultrasound drug delivery, trans-dermal ultrasound drug delivery, ultrasound hemostasis, cancer therapy, and ultrasound assisted thrombolysis[1] [2] It may use focused ultrasound (FUS) or unfocused ultrasound.

In the above applications, the ultrasound passes through human tissue where it is the main source of the observed biological effect (the oscillation of abrasive dental tools at ultrasonic frequencies therefore do not belong to this class). The ultrasound within tissue consists of very high frequency sound waves, between 800,000 Hz and 20,000,000 Hz, which cannot be heard by humans.

There is little evidence that active ultrasound is more effective than placebo treatment for treating patients with pain or a range of musculoskeletal injuries, or for promoting soft tissue healing.[3]

Medical uses

Relatively high power ultrasound can break up stony deposits or tissue, accelerate the effect of drugs in a targeted area, assist in the measurement of the elastic properties of tissue, and can be used to sort cells or small particles for research.

- Focused high-energy ultrasound pulses can be used to break calculi such as kidney stones and gallstones into fragments small enough to be passed from the body without undue difficulty, a process known as lithotripsy.

- Focused ultrasound sources may be used for cataract treatment by phacoemulsification.

- Ultrasound can ablate tumors or other tissue non-invasively. This is accomplished using a technique known as High Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU), also called focused ultrasound surgery (FUS surgery). This procedure uses generally lower frequencies than medical diagnostic ultrasound (250–2000 kHz), but significantly higher time-averaged intensities. The treatment is often guided by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI); the combination is then referred to as Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS).

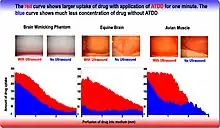

- Delivering chemotherapy to brain cancer cells and various drugs to other tissues is called acoustic targeted drug delivery (ATDD).[4] These procedures generally use high frequency ultrasound (1–10 MHz) and a range of intensities (0–20 W/cm2). The acoustic energy is focused on the tissue of interest to agitate its matrix and make it more permeable for therapeutic drugs.[5][6]

- Ultrasound has been used to trigger the release of anti-cancer drugs from delivery vectors including liposomes, polymeric microspheres and self-assembled polymeric.[1]

- Ultrasound is essential to the procedures of ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy and endovenous laser treatment for the non-surgical treatment of varicose veins.

- Ultrasound-assisted lipectomy is Liposuction assisted by ultrasound.

There are three potential effects of ultrasound. The first is the increase in blood flow in the treated area. The second is the decrease in pain from the reduction of swelling and edema. The third is the gentle massage of muscle tendons and/ or ligaments in the treated area because no strain is added and any scar tissue is softened. These three benefits are achieved by two main effects of therapeutic ultrasound. The two types of effects are: thermal and non thermal effects. Thermal effects are due to the absorption of the sound waves. Non thermal effects are from cavitation, microstreaming and acoustic streaming.[1]

Cavitational effects result from the vibration of the tissue causing microscopic bubbles to form, which transmit the vibrations in a way that directly stimulates cell membranes. This physical stimulation appears to enhance the cell-repair effects of the inflammatory response.

History

The first large scale application of ultrasound was around World War II. Sonar systems were being built and used to navigate submarines. It was realized that the high intensity ultrasound waves that they were using were heating and killing fish.[7] This led to research in tissue heating and healing effects. Since the 1940s, ultrasound has been used by physical and occupational therapists for therapeutic effects.

Physical therapy

Ultrasound is applied using a transducer or applicator that is in direct contact with the patient's skin. Gel is used on all surfaces of the head to reduce friction and assist transmission of the ultrasonic waves. Therapeutic ultrasound in physical therapy is alternating compression and rarefaction of sound waves with a frequency of 0.7 to 3.3 MHz. Maximum energy absorption in soft tissue occurs from 2 to 5 cm. Intensity decreases as the waves penetrate deeper. They are absorbed primarily by connective tissue: ligaments, tendons, and fascia (and also by scar tissue).[8]

Conditions for which ultrasound may be used for treatment include the following examples: ligament sprains, muscle strains, tendonitis, joint inflammation, plantar fasciitis, metatarsalgia, facet irritation, impingement syndrome, bursitis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and scar tissue adhesion. A review with five small placebo‐controlled trials from 2011, did not support the use of ultrasound in the treatment of acute ankle sprains and the potential treatment effects of ultrasound appear to be generally small and of probably of limited clinical importance, especially in the context of the usually short‐term recovery period for these injuries. [9]

Research tools

- Acoustic tweezers is an emerging tool for contactless separation, concentration and manipulation of microparticles and biological cells, using ultrasound in the low MHz range to form standing waves. This is based on the acoustic radiation force which causes particles to be attracted to either the nodes or anti-nodes of the standing wave depending on the acoustic contrast factor, which is a function of the sound velocities and densities of the particle and of the medium in which the particle is immersed.

- Application of focused ultrasound in conjunction with microbubbles has been shown to enable non-invasive delivery of epirubicin across the blood–brain barrier in mouse models [1] and non invasive delivery of GABA in non human primates.[10]

Research

- Using ultrasound to generate cellular effects in soft tissue has fallen out of favor as research has shown a lack of efficacy[11] and a lack of scientific basis for proposed biophysical effects.[12]

- According to a 2017 meta-analysis and associated practice guideline, Low intensity pulsed ultrasound should no longer been used for bone regeneration because high quality clinical studies failed to demonstrate a clinical benefit.[13][14]

- An additional effect of low-intensity ultrasound could be its potential to disrupt the blood–brain barrier for drug delivery.[15]

- Transcranial ultrasound is being tested for use in aiding tissue plasminogen activator treatment in stroke sufferers in the procedure called ultrasound-enhanced systemic thrombolysis.

- Ultrasound has been shown to act synergistically with antibiotics in killing bacteria.[16]

- Ultrasound has been postulated to allow thicker eukaryotic cell tissue cultures by promoting nutrient penetration.[17]

- Long-duration therapeutic ultrasound called sustained acoustic medicine is a daily slow-release therapy that can be applied to increase local circulation and theoretically accelerates healing of musculoskeletal tissues after an injury.[18] However there is some evidence to suggest this may not be effective.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Mo S, Coussios CC, Seymour L, Carlisle R (December 2012). "Ultrasound-enhanced drug delivery for cancer". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 9 (12): 1525–1538. doi:10.1517/17425247.2012.739603. PMID 23121385. S2CID 31178343.

- ↑ "Therapeutic Ultrasound: A Promising Future in Clinical Medicine". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- 1 2 Robertson VJ, Baker KG (July 2001). "A review of therapeutic ultrasound: effectiveness studies". Physical Therapy. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK). 81 (7): 1339–1350. doi:10.1093/ptj/81.7.1339. PMID 11444997.

- ↑ Lewis GK, Olbricht WL, Lewis GK (February 2008). "Acoustically enhanced Evans blue dye perfusion in neurological tissues". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2 (1): 20001–200017. doi:10.1121/1.2890703. PMC 3011869. PMID 21197390.

- ↑ Lewis GK, Olbricht W (2007). A phantom feasibility study of acoustic enhanced drug delivery to neurological tissue. p. 67. doi:10.1109/LSSA.2007.4400886. ISBN 978-1-4244-1812-1. S2CID 31498698. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ↑ "Highlights of upcoming acoustics meeting in New Orleans". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 2019-06-16. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ↑ Woo J. "A short History of the development of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology". esource Discovery Network, University of Oxford. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ↑ Watson T (2006). "Therapeutic Ultrasound". Archived from the original on 2007-08-21.

- ↑ van den Bekerom MP, van der Windt DA, Ter Riet G, van der Heijden GJ, Bouter LM (June 2011). "Therapeutic ultrasound for acute ankle sprains". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD001250. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001250.pub2. PMC 7088449. PMID 21678332.

- ↑ Constans, C., Ahnine, H., Santin, M., Lehericy, S., Tanter, M., Pouget, P., & Aubry, J. F. (2020). Non-invasive ultrasonic modulation of visual evoked response by GABA delivery through the blood brain barrier. Journal of Controlled Release, 318, 223-231 Archived 2020-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Robertson VJ, Baker KG (July 2001). "A review of therapeutic ultrasound: effectiveness studies". Physical Therapy. 81 (7): 1339–1350. doi:10.1093/ptj/81.7.1339. PMID 11444997.

- ↑ Baker KG, Robertson VJ, Duck FA (July 2001). "A review of therapeutic ultrasound: biophysical effects". Physical Therapy. 81 (7): 1351–1358. doi:10.1093/ptj/81.7.1351. PMID 11444998.

- ↑ Schandelmaier S, Kaushal A, Lytvyn L, Heels-Ansdell D, Siemieniuk RA, Agoritsas T, et al. (February 2017). "Low intensity pulsed ultrasound for bone healing: systematic review of randomized controlled trials". BMJ. 356: j656. doi:10.1136/bmj.j656 (inactive 31 October 2021). PMC 5484179. PMID 28348110.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - ↑ Poolman RW, Agoritsas T, Siemieniuk RA, Harris IA, Schipper IB, Mollon B, et al. (February 2017). "Low intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) for bone healing: a clinical practice guideline". BMJ. 356: j576. doi:10.1136/bmj.j576. PMID 28228381.

- ↑ Vlachos F, Tung YS, Konofagou E (September 2011). "Permeability dependence study of the focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening at distinct pressures and microbubble diameters using DCE-MRI". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 66 (3): 821–830. doi:10.1002/mrm.22848. PMC 3919956. PMID 21465543.

- ↑ Carmen JC, Roeder BL, Nelson JL, Beckstead BL, Runyan CM, Schaalje GB, et al. (April 2004). "Ultrasonically enhanced vancomycin activity against Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms in vivo". Journal of Biomaterials Applications. 18 (4): 237–245. doi:10.1177/0885328204040540. PMC 1361255. PMID 15070512.

- ↑ Pitt WG, Ross SA (2003). "Ultrasound increases the rate of bacterial cell growth". Biotechnology Progress. 19 (3): 1038–1044. doi:10.1021/bp0340685. PMC 1361254. PMID 12790676.

- ↑ Rigby J, Taggart R, Stratton K, Lewis Jr JK, Draper DO (2015). "Multi-Hour Low Intensity Therapeutic Ultrasound (LITUS) Produced Intramuscular Heating by Sustained Acoustic Medicine". J Athl Train.

External links

- Video: Physical Therapy Ultrasound; What is it? Archived 2020-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Watson, T. (2006). "Therapeutic Ultrasound". Archived 2021-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- International Society for Therapeutic Ultrasound Archived 2021-04-25 at the Wayback Machine