Wrist osteoarthritis

| Wrist osteoarthritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Osteoarthritis of the wrist |

| |

| Specialty | Orthopedic |

Wrist osteoarthritis is a group of mechanical abnormalities resulting in joint destruction, which can occur in the wrist. These abnormalities include degeneration of cartilage and hypertrophic bone changes, which can lead to pain, swelling and loss of function. Osteoarthritis of the wrist is one of the most common conditions seen by hand surgeons.[1][2]

Osteoarthritis of the wrist can be idiopathic, but it is mostly seen as a post-traumatic condition.[1][3] There are different types of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC) is the most common form, followed by scaphoid non-union advanced collapse (SNAC).[4] Other post-traumatic causes such as intra-articular fractures of the distal radius or ulna can also lead to wrist osteoarthritis, but are less common.

Types

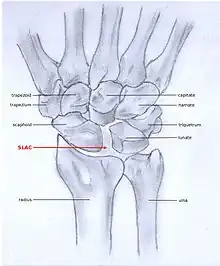

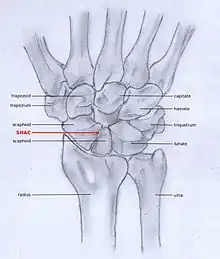

SLAC and SNAC are two patterns of wrist osteoarthritis, following predictable patterns depending on the type of underlying injury. SLAC is caused by scapholunate ligament rupture, and SNAC is caused by a scaphoid fracture which does not heal and because of that will develop in a non-union fracture. SLAC is more common than SNAC; 55% of the patients with wrist osteoarthritis has a SLAC wrist.[4]

SLAC

Scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC) is a predictable pattern of wrist osteoarthritis that results from untreated long-standing scapholunate instability, which in turn is secondary to a rupture of the scapholunate ligament.[5] The main type of such misalignment is dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) which is where the lunate angulates to the posterior side of the hand.[3][6]

SNAC

Scaphoid non-union fractures changes scaphoid bone shape, which leads to abnormal joint kinematics. Due to lack of stability from the distorted scaphoid, a DISI can be developed.[3][6] Scaphoid Non-union Advanced collapse (SNAC) is the pattern of osteoarthritis that eventually develops by this process.

Stages

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis can be classified into four stages.[1][7] These stages are similar between SLAC and SNAC wrists. Each stage has a different treatment.

- Stage I: the osteoarthritis is only localized in the distal scaphoid and radial styloid.

- Stage II: the osteoarthritis is localized in the entire radioscaphoid joint.

- Stage III: the osteoarthritis is localized in the entire radioscaphoid joint with involvement of the capitolunate joint.

- Stage IV: the osteoarthritis is located in the entire radiocarpal joint and in the intercarpal joints. It also may involve the distal radio-ulnar joint (DRUJ).

Stage I

Stage I Stage II

Stage II Stage III

Stage III Stage IV

Stage IV

Signs and symptoms

The most common initial symptom of wrist osteoarthritis is joint pain.[8][9] The pain is brought on by activity and increases when there is activity after resting. Other signs and symptoms, as with any joint affected by osteoarthritis, include:

- Morning stiffness, which usually lasts less than 30 minutes. This is also present in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but in those patients this typically lasts for more than 45 minutes.

- Swelling of the wrist.

- Crepitus (crackling), which is felt when the hand is moved passively.[9]

- Joint locking, where the joint is fixed in an extended position.

- Joint instability.

These symptoms can lead to loss of function and less daily activity.[8]

Mechanism

In order to understand the cause of post-traumatic wrist osteoarthritis it is important to know and understand the anatomy of the wrist. The hand is subdivided into three parts:

The wrist consists of eight small carpal bones. Each of these carpal bones has a different size and shape. They contribute towards the stability of the wrist and are ranked in two rows, each consisting of four bones.

Proximal row

From lateral to medial and when viewed from anterior, the proximal row is formed by the:

Distal row

From lateral to medial and when viewed from anterior, the distal row is formed by the:

Diagnosis

Osteoarthritis of the wrist is predominantly a clinical diagnosis, and thus is primarily based on the patients medical history, physical examination and wrist X-rays.[3]

Medical history

Medical history of the patient should include age, hand dominance, occupation and most important an evaluation of recent hand traumas.[8]

Physical examination

Examination will often show tenderness at the radioscaphoid joint (when palpated or while moving the radioscaphoid joint), dorsal radial swelling and instability of the wrist joint.[3] Notice that people may say they have trouble with rising from a chair when pressure is exerted on the hands by pushing against the handrail. Younger people may complain about not being able to do push-ups anymore because of a painful hand.

There are a number of tests and actions that can be performed when a patient is suspected of having osteoarthritis caused by SLAC or SNAC.

SLAC:

- Tenderness 1 cm above Lister’s tubercle

Tests:

- Watson's test

- Finger extension test

SNAC:

- Tenderness at the anatomical snuff box

- Painful pronation and supination when performed against resistance

- Pain during axial pressure

X-rays

Osteoarthritis between the radius bone and the carpals is indicated by a radiocarpal joint space of less than 2mm.[10]

SLAC

Because SLAC results from scapholunate ligament rupture, there is a larger space between the two bones, also known as the Terry Thomas sign. Osteoarthritis and a space larger than 3 mm is suspicious and a space larger than 5 mm is a proven SLAC pathology.[11] Scaphoid instability due to the ligament rupture can be stactic or dynamic.[12] When the X-ray is diagnostic and there is a convincing Terry Thomas sign it is a static scaphoid instability. When the scaphoid is made unstable by either the patient or by manipulation by the examining physician it is a dynamic instability.[12]

SNAC

In order to diagnose a SNAC wrist you need a PA view X-ray and a lateral view X-ray. As in SLAC, the lateral view X-ray is performed to see if there is a DISI.[13] Computed tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are rarely used to diagnose SNAC or SLAC wrist osteoarthritis because there is no additional value.[8] Also, these techniques are much more expensive than a standard X-ray. CT or MRI may be used if there is a strong suspicion for another underlying pathology or disease.[8]

Treatment

Post-traumatic wrist osteoarthritis can be treated conservatively or with a surgical intervention. In many patients, a conservative (non-surgical) approach is sufficient. Because osteoarthritis is progressive and symptoms may get worse, surgical treatment is advised in any stage.[1][2][3][7]

Stage I

For stage I, normally, nonsurgical treatment is sufficient. This type of therapy includes the use of splint or cast immobilization, injections of corticosteroid in the pain causing joints and the use of a systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug to reduce pain and improve the functional use of the affected joint. However, the amount of pain that can be suppressed by nonsurgical therapy is limited and with the progression of the wrist osteoarthritis surgical treatment is inevitable.[14]

In stage I surgical treatment often consists of neurectomy of the posterior interosseous nerve and is often combined with other procedures. In the case of a SLAC, the scapholunate ligament can be reconstructed in combination with a radial styloidectomy, in which the radial styloid is surgically removed from the distal radius. In the case of a SNAC, the scaphoid can be reconstructed by fixating the scaphoid with a screw or by placing a bone graft(Matti-Russe procedure) to increase the stability of the scaphoid.[14]

Stage II

In the treatment of stage II wrist osteoarthritis, there are two treatment options that have proved to be most successful. The first treatment option is proximal row carpectomy. During this surgical intervention the proximal row of the carpal bones is removed (scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform).[15] It is important that the radioscaphocapitate ligament is left intact, because if the ligament is not preserved the capitate bone will translate to the ulnar side of the wrist and move away from the distal radius.[1][16] The new formed joint between the capitate and the lunate fossa of the distal radius is not as congruent as the former scaphoid-lunate-radius joint,[17][18] however the results of proximal row carpectomy are generally excellent.[18][19][20] In patients older than 40 years proximal row carpectomy is preferred because these patients have a small chance of developing osteoarthritis in the new formed capitate-radial joint during their remaining life.[7][21]

Patients younger than 40 years have a big chance to develop osteoarthritis in the radiocapitate joint. These patients have longer to live, therefore the incongruence of the joint will exist for a longer time. Thus, in this patient population four-corner arthrodesis is the treatment of first choice.[7] The capitate, lunate, hamate and triquetrum are bounded together in this procedure and the scaphoid is excised.[1][15] Before the arthrodesis is executed, the lunate must be reduced out of DISI position.[15] Because the radiolunate joint is typically preserved in stage II SLAC and SNAC wrists, this joint can be the only remaining joint of the proximal wrist. Both procedures are often combined with wrist denervation, as described in the text of treatment stage I.

Stage III

The only treatment option for stage III wrist osteoarthritis is four-corner arthrodesis, as described above in stage II. Proximal row carpectomy is not an option, because in stage III patients the capitate is already affected by the osteoarthritis. So, this procedure would merely lead to a new painful joint.

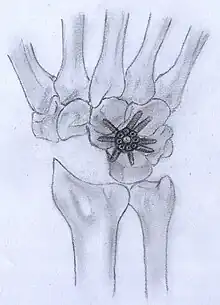

Stage IV

In this stage there are two surgical treatment options; total wrist arthroplasty and total wrist arthrodesis. Total wrist arthrodesis has become the standard surgical treatment for patients with stage IV wrist osteoarthritis. During this procedure the carpal bones are all fused together and are then fastened to the distal radius.[15] Patients who still want to undertake heavy labor benefit the most of this surgical approach,[22] because after surgery and recovery this is still possible. However, the arc of motion is extremely diminished by this type of surgery.

The best option for those who wish for a motion-sparing procedure is total wrist arthroplasty. However, impact loading should be avoided, an object heavier than 4.5 kg should not be lifted.[23] So, this surgical approach has postoperative activity restrictions. Nevertheless, patients with a total wrist arthrodesis on one side and a total wrist arthroplasty on the other, prefer the total wrist arthroplasty.[24] The procedure exists of a couple of elements. First, the proximal row is removed and the distal row is fastened to the metacarpals. Then, one side of the arthroplasty is placed upon the distal row and the other side on the distal radius. Additionally, the head of the ulna is removed.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Weiss, KE; Rodner, CM (May–June 2007). "Osteoarthritis of the Wrist, Review article". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 32A (5): 725–46. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.02.003. PMID 17482013.

- 1 2 Talwalkar, SC; Hayton MC; Stanley JK (2008). "Wrist osteoarthritis". Scand J Surg. 97 (4): 305–9. doi:10.1177/145749690809700406. PMID 19211384. S2CID 43701956.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shah, CM; Stern PJ (2013). "Scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC) and scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse (SNAC) wrist arthritis". Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 6 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1007/s12178-012-9149-4. PMC 3702758. PMID 23325545.

- 1 2 Bisneto EN, Freitas MC, Paula EJ, Mattar R, Zumiotti AV (2011). "Comparison between proximal row carpectomy and four-corner fusion for treating osteoarthrosis following carpal trauma: a prospective randomized study". Clinics (Sao Paulo). 66 (1): 51–5. doi:10.1590/s1807-59322011000100010. PMC 3044580. PMID 21437436.

- ↑ Tischler, Brian T.; Diaz, Luis E.; Murakami, Akira M.; Roemer, Frank W.; Goud, Ajay R.; Arndt, William F.; Guermazi, Ali (2014). "Scapholunate advanced collapse: a pictorial review". Insights into Imaging. 5 (4): 407–417. doi:10.1007/s13244-014-0337-1. ISSN 1869-4101. PMC 4141341. PMID 24891066.

- 1 2 Omori, S; Moritomo, H; Omokawa, S; Murase, T; Sugamoto, K; Yoshikawa, H (July 2013). "In vivo 3-dimensional analysis of dorsal intercalated segment instability deformity secondary to scapholunate dissociation: a preliminary report". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 38 (7): 1346–55. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.04.004. PMID 23790423.

- 1 2 3 4 Strauch, RJ (Apr 2011). "Scapholunate advanced collapse and scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse arthritis--update on evaluation and treatment". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 36 (4): 729–735. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.01.018. PMID 21463735.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sinusas, K (2012). "Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment". Am Fam Physician. 85 (1): 49–56. PMID 22230308.

- 1 2 Manek, NJ; Lane NE (2000). "Osteoarthritis: current concepts in diagnosis and management". Am Fam Physician. 61 (6): 1795–804. PMID 10750883.

- ↑ "Radiocarpal joint space". radref.org. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- ↑ Wolfe, SW; Hotchkiss, RN (2011). Green's Operative Hand Surgery, 6th Edition (6th ed.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-1-4160-5279-1.

- 1 2 Jupiter, JB; Edwards, JE (1991). Flynn's hand surgery, fourth edition; chapter 10 dislocations and fracture dislocations of the carpus (4th ed.). Baltimore: Williams&Wilkins. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0-683-04490-4.

- ↑ Novelline, RA (2004). Squire's fundamentals of radiology, 6th Edition (6th ed.). United States of America: President and fellows of Harvard college. ISBN 978-0-674-01279-0.

- 1 2 Dacho, A; Grundel, J (2006). "Long-term results of midcarpal arthrodesis in the treatment of scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse (SNAC-Wrist) and scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC-Wrist)". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 56 (2): 139–144. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000194245.94684.54. PMID 16432320. S2CID 43178329.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berger, RA; Weiss, APC (2004). Hand surgery, first edition; Principles of Limited Wrist Arthrodesis (1st ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1290–1295, 1320–1329, 1352–1373. ISBN 978-0-7817-2874-4.

- ↑ Berger, RA; Landsmeer, JM (1990). "The palmar radiocarpal ligaments: a study of adult and fetal hunman wrist joints". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 15 (6): 847–854. doi:10.1016/0363-5023(90)90002-9. PMC 2328843. PMID 2269772.

- ↑ Inglis, AE; Jones, EC (1977). "Proximal row carpectomy for diseases of the proximal row". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 59A (4): 460–463. PMID 863938.

- 1 2 Imrbiglia, JE; Broudy, AS; Hagberg, WC (1990). "Proximal row carpectomy: clinical evaluation". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 15 (3): 426–430. doi:10.1016/0363-5023(90)90054-U. PMID 2348060.

- ↑ Tomaino, MM; Delsignore, J; Burton, RI (1994). "Long-term results following proximal row carpectomy". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 19A (4): 694–703. doi:10.1016/0363-5023(94)90284-4. PMID 7963335.

- ↑ DiDonna, ML; Kiefhaber, TR; Stern, PJ (2004). "Proximal row carpectomy: study with a minimum of ten years of follow-up". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 86A (11): 2359–2365. doi:10.2106/00004623-200411000-00001. PMID 15523004.

- ↑ Wall, LB; DiDonna, ML (Aug 2013). "Proximal row carpectomy: minimum 20-year follow-up". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 38 (8): 1498–1504. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.04.028. PMID 23809467.

- ↑ Weiss, APC; Hastings, H (Jan 1995). "Wrist arthrodesis for traumatic conditions: a study of plate and local bone graft application". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 20A (5): 50–56. doi:10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80058-9. PMID 7722266.

- ↑ Anderson, MC; Adams, BD (2005). "Total wrist arthroplasty". Hand Clinics. 21 (4): 621–630. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2005.08.014. PMID 16274871.

- ↑ Vicar, AJ; Burton, RI (1988). "Surgical management of the rheumatoid wrist-fusion or arthroplasty". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 11A (6): 790–797. doi:10.1016/s0363-5023(86)80224-6. PMID 3794231.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wrist osteoarthritis. |