Scaphoid fracture

| Scaphoid fracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Carpal scaphoid fracture, carpal navicular fracture[1] | |

| |

| An X-ray showing a fracture through the waist of the scaphoid | |

| Specialty | Hand surgery, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Pain at the base of the thumb, swelling[2] |

| Complications | Nonunion, avascular necrosis, arthritis[2][1] |

| Types | Proximal, medial, distal[2] |

| Causes | Fall on an outstretched hand[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Examination, X-rays, MRI, bone scan[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Distal radius fracture, De Quervain's tenosynovitis, scapholunate dissociation, wrist sprain[2][1] |

| Prevention | Wrist guards[1] |

| Treatment | Not displaced: Cast[2] Displaced: Surgery[2] |

| Prognosis | Healing may take up to six months[1] |

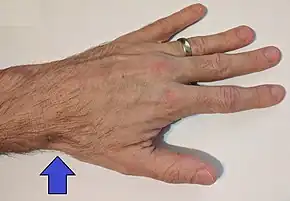

A scaphoid fracture is a break of the scaphoid bone in the wrist.[1] Symptoms generally includes pain at the base of the thumb which is worse with use of the hand.[2] The anatomic snuffbox is generally tender and swelling may occur.[2] Complications may include nonunion of the fracture, avascular necrosis, and arthritis.[1][2]

Scaphoid fractures are most commonly caused by a fall on an outstretched hand.[2] Diagnosis is generally based on examination and medical imaging.[2] Some fractures may not be visible on plain X-rays.[2] In such cases a person may be casted with repeat X-rays in two weeks or an MRI or bone scan may be done.[2]

The fracture may be preventable by using wrist guards during certain activities.[1] In those in whom the fracture remains well aligned a cast is generally sufficient.[2] If the fracture is displaced then surgery is generally recommended.[2] Healing may take up to six months.[1] It is the most common wrist bone fracture.[3] Males are affected more often than females.[2]

Signs and symptoms

People with scaphoid fractures generally have snuff box tenderness.

Focal tenderness is usually present in one of three places: 1) volar prominence at the distal wrist for distal pole fractures; 2) anatomic snuff box for waist or midbody fractures; 3) distal to Lister's tubercle for proximal pole fractures.[4]

Complications

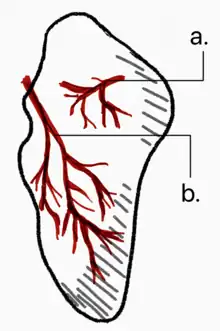

Avascular necrosis (AVN) is a common complication of a scaphoid fracture. Since the scaphoid blood supply comes from two different vascular branches of the radial artery, fractures can limit access to blood supply.[5]

Risk of AVN depends on the location of the fracture.

- Fractures in the proximal 1/3 have a high incidence of AVN (~30%)

- Waist fractures in the middle 1/3 is the most frequent fracture site and has moderate risk of AVN.

- Fractures in the distal 1/3 are rarely complicated by AVN.

Non union can also occur from undiagnosed or undertreated scaphoid fractures. Arterial flow to the scaphoid enters via the distal pole and travels to the proximal pole. This blood supply is tenuous, increasing the risk of nonunion, particularly with fractures at the wrist and proximal end.[4] If not treated correctly non-union of the scaphoid fracture can lead to wrist osteoarthritis.

Symptoms may include aching in the wrist, decreased range of motion of the wrist, and pain during activities such as lifting or gripping. If x-ray results show arthritis due to an old break, the treatment plan will first focus on treating the arthritis through anti-inflammatory medications and wearing a splint when an individual feels pain in the wrist. If these treatments do not help the symptoms of arthritis, steroid injections to the wrist may help alleviate pain. Should these treatments not work, surgery may be required.[6]

Mechanism

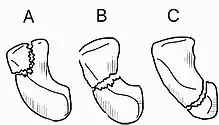

Fractures of scaphoid can occur either with direct axial compression or with hyperextension of the wrist, such as a fall on the palm on an outstretched hand (FOOSH). 10%-20% of fractures are at the proximal pole, 60%-80% are at the waist (middle), and the remainder occur at the distal pole.[4][7][5]

The 'Herbert classification' is a system of categorizing scaphoid fractures.[8]

| A | Acute/stable | A1 | Tubercle |

| A2 | Nondisplaced waist | ||

| B | Acute/unstable | B1 | Oblique/distal third |

| B2 | Displaced waist | ||

| B3 | Proximal third | ||

| B4 | Fracture dislocation | ||

| B5 | Comminuted fracture | ||

| C | Delayed union | ||

| D | Established non-union | D1 | Fibrous |

| D2 | Sclerotic | ||

Diagnosis

Scaphoid fractures are often diagnosed by PA and lateral X-rays. However, not all fractures are apparent initially.[7] Therefore, people with tenderness over the scaphoid (those who exhibit pain to pressure in the anatomic snuff box ) are often splinted in a thumb spica for 7–10 days at which point a second set of X-rays is taken.[7] If there was a hairline fracture, healing will now be apparent. Even then a fracture may not be apparent. A CT Scan can then be used to evaluate the scaphoid with greater resolution. The use of MRI, if available, is preferred over CT and can give one an immediate diagnosis.[9] Bone scintigraphy is also an effective method for diagnosis fracture which do not appear on Xray.[10]

A subtle scaphoid fracture

A subtle scaphoid fracture A more obvious scaphoid fracture on a scaphoid view X ray

A more obvious scaphoid fracture on a scaphoid view X ray Radiolucency around a 12 days old scaphoid fracture that was initially barely visible.[11]

Radiolucency around a 12 days old scaphoid fracture that was initially barely visible.[11] Fracture of the tubercle of the scaphoid bone of the wrist

Fracture of the tubercle of the scaphoid bone of the wrist

Treatment

Treatment of scaphoid fractures is guided by the location in the bone of the fracture (proximal, waist, distal), displacement (or instability) of the fracture, and patient tolerance for cast immobilization.

Non displaced or minimally displaced waist and distal fractures have a high rate of union with closed cast management. The choice of short arm, short arm thumb spica or long arm cast is debated in the medical literature and no clear consensus or proof of the benefit of one type of casting or another has been shown; although it is generally accepted to use a short arm or short arm thumb spica for non displaced fractures.[7] Non displaced or minimally displaced fracture can also be treated with percutaneous or minimal incision surgery which if performed correctly has a high union rate, low morbidity and faster return to activity than closed cast management.[12]

Fractures that are more proximal take longer to heal. It is expected the distal third will heal in 6 to 8 weeks, the middle third will take 8–12 weeks, and the proximal third will take 12–24 weeks.[7][5] The Scaphoid receives its blood supply primarily from lateral and distal branches of the radial artery. Blood flows from the top/distal end of the bone in a retrograde fashion down to the proximal pole; if this blood flow is disrupted by a fracture, the bone may not heal. Surgery is necessary at this point to mechanically mend the bone together.

Percutaneous screw fixation is recommended over an open surgical approach when it is possible to achieve acceptable bone alignment closed as minimal incisions can preserves the palmar ligament complex and local vasculature, and help avoid soft tissue complications. This surgery includes screwing the scaphoid bone back together at the most perpendicular angle possible to promote quicker and stronger healing of the bone. Internal fixation can be done dorsally with a percutaneous incision and arthroscopic assistance or via a minimal open dorsal approach,[13] or via a volar approach in which case slight excavation of the edge of the trapezium bone may be necessary to reach the scaphoid as 80% of this bone is covered with articular cartilage, which makes it difficult to gain access to the scaphoid.[14]

Epidemiology

Scaphoid fractures account for 50%-80% of carpal injuries.[5] Fractures of the scaphoid are common in young males.[15] They are less common in children and older adults because the distal radius is weaker contributor to the wrist and more likely to fracture in these age groups.[7]

Terminology

These are also called navicular fractures (the scaphoid also being called the carpal navicular), although this can be confused with the navicular bone in the foot.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Scaphoid Fracture of the Wrist". AAOS. March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Phillips, TG; Reibach, AM; Slomiany, WP (1 September 2004). "Diagnosis and management of scaphoid fractures". American Family Physician. 70 (5): 879–84. PMID 15368727.

- ↑ Tada, K; Ikeda, K; Okamoto, S; Hachinota, A; Yamamoto, D; Tsuchiya, H (2015). "Scaphoid Fracture--Overview and Conservative Treatment". Hand Surgery. 20 (2): 204–9. doi:10.1142/S0218810415400018. PMID 26051761.

- 1 2 3 deWeber, Kevin. "Scaphoid fractures". UpToDate.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- 1 2 3 4 1967-, Egol, Kenneth A. (2015). Handbook of fractures. Koval, Kenneth J., Zuckerman, Joseph D. (Joseph David), 1952-, Ovid Technologies, Inc. (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health. ISBN 978-1451193626. OCLC 960851324.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jones, Bertrand MD (2010). "Scaphoid Fracture of the Wrist". Ortho Info. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Archived from the original on December 7, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Essentials of musculoskeletal care. Sarwark, John F. Rosemont, Ill.: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2010. ISBN 978-0892035793. OCLC 706805938.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ White, Timothy O.; Mackenzie, Samuel P.; Gray, Alasdair J. (2016). "12. Wrist and carpus". McRae's Orthopaedic Trauma and Emergency Fracture Management (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 247–248. ISBN 978-0-7020-5728-1. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2022-09-08.

- ↑ "BestBets: Magnetic resonance imaging of suspected scaphoid fractures". Archived from the original on 2010-06-16.

- ↑ Yin ZG, Zhang JB, Kan SL, Wang XG (March 2010). "Diagnosing suspected scaphoid fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 468 (3): 723–34. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-1081-6. PMC 2816764. PMID 19756904.

- ↑ Jarraya, Mohamed; Hayashi, Daichi; Roemer, Frank W.; Crema, Michel D.; Diaz, Luis; Conlin, Jane; Marra, Monica D.; Jomaah, Nabil; Guermazi, Ali (2013). "Radiographically Occult and Subtle Fractures: A Pictorial Review". Radiology Research and Practice. 2013: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2013/370169. ISSN 2090-1941. PMC 3613077. PMID 23577253. CC-BY 3.0 Archived 2011-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Gutow AP (Aug 2007). "Percutaneous fixation of scaphoid fractures". J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 15 (8): 474–85. doi:10.5435/00124635-200708000-00004. PMID 17664367.

- ↑ Gutow AP (Aug 2007). "Percutaneous fixation of scaphoid fractures". J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 15 (8): 474–85. doi:10.5435/00124635-200708000-00004. PMID 17664367.

- ↑ Kastelec, Matej. "Percutaneous Screw Fixation". AO Foundation. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Beasley's Surgery of the Hand. Thieme New York. 2003. p. 188. ISBN 9781282950023.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- AAFP: Diagnosis and Management of Scaphoid Fractures Archived 2008-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Wheeless: Scaphoid fracture Archived 2007-09-12 at the Wayback Machine