Cerliponase alfa

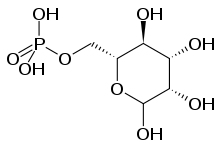

Structure of tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (TPP1) enzyme for which cerliponase alfa is a replacement | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Brineura |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Enzyme[1] |

| Main uses | Late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2)[2] |

| Side effects | Fever, vomiting, upper respiratory tract infection, allergic reactions[1] |

| Routes of use | Intraventricular |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| US NLM | Cerliponase alfa |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C2657H4042N734O793S11 |

| Molar mass | 59308.2298 g·mol−1 |

Cerliponase alfa, marketed as Brineura, is a medication used to treat late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2).[2] In symptomatic children over three years old it slows loss of muscle function.[2] It is given by direct infusion into the ventricles of the brain.[1][3]

Common side include fever, vomiting, headache,seizures, upper respiratory tract infection, and allergic reactions.[1][2] Other side effects may include arrhythmias, meningitis, and anaphylaxis.[2] It works by replacing the missing enzyme tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (TPP1).[1]

Cerliponase alfa was approved for medical use in the United States and Europe in 2017.[2][1] In Canada it costs about 844,000 CAD per year as of 2019.[4] In the United States this amount costs about 710,000 USD.[5]

Medical use

Cerliponase alfa is administered via intracerebroventricular infusion directly to the cerebrospinal fluid using an implanted catheter.[6] The catheter system used in the U.S. is a Codman Ventricular Catheter with a B Braun Perfusor Space Infusion Pump.[7]The catheter must be surgically implanted by a trained professional. The drug is administered to patients every two weeks followed by an electrolyte infusion to wash residue drug out of the catheter tube. The dose is slowly dripped in so each infusion takes approximately 4.5 hours. Patients are regularly treated with corticosteroids or antihistamines prior to each infusion.[6]

Cerliponase alfa is administered into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by infusion via a specific surgically implanted reservoir and catheter in the head (intraventricular access device).[8] Brineura must be administered under sterile conditions to reduce the risk of infections, and treatment should be managed by a health care professional knowledgeable in intraventricular administration.[8] The complete Brineura infusion, including the required infusion of intraventricular electrolytes, lasts approximately 4.5 hours.[8] Pre-treatment of patients with antihistamines with or without antipyretics (drugs for prevention or treatment of fever) or corticosteroids is recommended 30 to 60 minutes prior to the start of the infusion.[8]

Cerliponase alfa should not be administered to patients if there are signs of acute intraventricular access device-related complications (e.g., leakage, device failure or signs of device-related infection such as swelling, erythema of the scalp, extravasation of fluid, or bulging of the scalp around or above the intraventricular access device).[8] In case of intraventricular access device complications, health care providers should discontinue infusion of Brineura and refer to the device manufacturer's labeling for further instructions.[8] Additionally, health care providers should routinely test patient CSF samples to detect device infections.[8] Brineura should also not be used in patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunts (medical devices that relieve pressure on the brain caused by fluid accumulation).[8]

Health care providers should also monitor vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, etc.) before the infusion starts, periodically during infusion and post-infusion in a health care setting.[8] Health care providers should perform electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring during infusion in patients with a history of slow heart rate (bradycardia), conduction disorder (impaired progression of electrical impulses through the heart) or structural heart disease (defect or abnormality of the heart), as some patients with CLN2 disease can develop conduction disorders or heart disease.[8] Hypersensitivity reactions have also been reported in Brineura-treated patients.[8] Due to the potential for anaphylaxis, appropriate medical support should be readily available when Brineura is administered.[8] If anaphylaxis occurs, infusion should be immediately discontinued and appropriate treatment should be initiated.[8]

Dosage

It is given at a dose of 300 mg once every two weeks.[3]

Mechanism of action

Cerliponase alfa is an approximately 59 kDa molecule that codes for 544 amino acids in its proenzyme form while the activated mature enzyme only codes for 368 amino acids. Five amino acid residues have N-linked glycosylation sites.[6] These five residues have additional mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) targeting sequences which function to target enzymes to the lysosome. When the cerliponase alfa proenzyme reaches target neurons during administration, it binds mannose-6-phosphate receptors on the cell surface to trigger vesicle formation around the receptor-proenzyme complex.[9][10] The more neutral pH of the cytosol promotes binding of the proenzyme's M6P targeting sequences to their receptors. Once brought into the cell, the receptor-proenzyme complex vesicle is transported to the lysosome where the lower pH promotes both dissociation of the proenzyme from the receptor and activation of the proenzyme to its active catalytic form via cleavage of the proenzyme sequence.[9][11]

Like natural TPP1, cerliponase alfa functions as a serine protease, cleaving N-terminal tripeptides from a broad range of protein substrates. The enzyme uses a catalytic triad active site composed of the three amino acids, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and serine. Serine functions as the amino acid that performs the nucleophilic attack during the ping pong catalytic activity of a serine protease.[12] The products of this reaction are a tripeptide and the remaining length of the protein substrate with a new N-terminal end that can be cleaved again. In CLN2 disease, TPP1 is deficient or not made at all, meaning that proteins are unable to be degraded in the lysosome and accumulate, leading to damage in nerves. As a protein, cerliponase alfa gets degraded by proteolysis.[6] Therefore, cerliponase alfa is administered repeatedly to maintain sufficient levels of the recombinant TPP1 enzyme in place of the deficient form to degrade proteins and prevent further build up. Cerliponase alfa is a treatment that can potentially slow disease progression but does not cure the disease itself.[9]

History

TPP1 was identified as the enzyme deficient in CLN2 Batten disease in 1997, via biochemical analysis that identified proteins missing a mannose-6-phosphate lysosomal targeting sequence.[13] A gel electrophoresis was run for known brain proteins with lysosomal targeting sequences to see if a band was missing, indicating a deficiency in that protein. A band appeared to be missing at approximately 46 kDa, confirming its role in CLN2 disease, and almost the entire gene for this unknown protein was sequenced. The gene is located on chromosome 11.[14] Today, it is known that varying mutation types occur in various locations of the gene including the proenzyme region, the mature enzyme region, or the signal sequence regions.[15] After discovery, the recombinant form of TPP1, cerliponase alfa, was first produced in 2000, followed by testing in animal models until 2014.[16] In 2012, BioMarin began the first clinical trial on affected patients using their recombinant DNA technology cerliponase alfa which is synthesized using Chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cell lines.[7]

After the success of this clinical trial, the U.S. FDA approved the marketing of cerliponase alfa to patients with CLN2 disease. The approval only applied to patients three years or older as the FDA wants to have more data available on children under the age of three before approving it for younger patients.[8] A ten-year study is being performed to assess the long term effects of continued use of this drug.[8][17] Cerliponase alfa is developed by BioMarin Pharmaceutical and the drug application was granted both orphan drug designation to provide incentives for rare disease research and the tenth Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher.[8] Cerliponase alfa was also approved by European Medicines Agency (EMA) on 30 May 2017.[18] In the United Kingdom NICE evaluated cerliponase alfa for the treatment of CLN2 and deemed it not cost-effective.[19][20] BioMarin announced that the price per infusion is $27,000, coming to $702,000 per year for treatment, though using Medicaid can decrease the cost.[21]

In March 2018, cerliponase alfa was approved in the United States as a treatment for a specific form of Batten disease.[8][22] Cerliponase alfa is the first FDA-approved treatment to slow loss of walking ability (ambulation) in symptomatic pediatric patients three years of age and older with late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2), also known as tripeptidyl peptidase-1 (TPP1) deficiency.[8]

The efficacy of cerliponase alfa was established in a non-randomized, single-arm dose escalation clinical study in 22 symptomatic pediatric patients with CLN2 disease and compared to 42 untreated patients with CLN2 disease from a natural history cohort (an independent historical control group) who were at least three years old and had motor or language symptoms.[8] Taking into account age, baseline walking ability and genotype, cerliponase alfa-treated patients demonstrated fewer declines in walking ability compared to untreated patients in the natural history cohort.[8]

The safety of cerliponase alfa was evaluated in 24 patients with CLN2 disease aged three to eight years who received at least one dose of cerliponase alfa in clinical studies.[8] The trial was conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and Italy.[22] The safety and effectiveness of cerliponase alfa has not been established in patients less than three years of age.[8]

Brineura-treated patients were compared to untreated patients from a natural history cohort by assessing disease progression through Week 96 of treatment.[22] The investigators measured the loss of ability to walk or crawl using the Motor domain of the CLN2 Clinical Rating Scale.[22] Scores from the Motor domain of the scale range from 3 (grossly normal) to 0 (profoundly impaired).[22]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires the cerliponase alfa manufacturer to further evaluate the safety of cerliponase alfa in CLN2 patients below the age of two years, including device related adverse events and complications with routine use.[8] In addition, a long-term safety study will assess cerliponase alfa treated CLN2 patients for a minimum of ten years.[8]

The application for cerliponase alfa was granted priority review designation, breakthrough therapy designation, orphan drug designation, and a rare pediatric disease priority review voucher.[8] The FDA granted approval of Brineura to BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.[8]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers it to be a first-in-class medication.[23]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Brineura". Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "DailyMed - BRINEURA- cerliponase alfa kit". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- 1 2 "Cerliponase Alfa Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Pharmacoeconomic Review Report" (PDF). CADTH. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Cerliponase Alfa Prices and Cerliponase Alfa Coupons - GoodRx". GoodRx. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Brineura- cerliponase alfa kit". DailyMed. 18 December 2018. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- 1 2 Markham A (July 2017). "Cerliponase Alfa: First Global Approval". Drugs. 77 (11): 1247–1249. doi:10.1007/s40265-017-0771-8. PMID 28589525. S2CID 25845031.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "FDA approves first treatment for a form of Batten disease". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 27 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 Johnson TB, Cain JT, White KA, Ramirez-Montealegre D, Pearce DA, Weimer JM (March 2019). "Therapeutic landscape for Batten disease: current treatments and future prospects". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 15 (3): 161–178. doi:10.1038/s41582-019-0138-8. PMC 6681450. PMID 30783219.

- ↑ Mukherjee AB, Appu AP, Sadhukhan T, Casey S, Mondal A, Zhang Z, Bagh MB (January 2019). "Emerging new roles of the lysosome and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses". Molecular Neurodegeneration. 14 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s13024-018-0300-6. PMC 6335712. PMID 30651094.

- ↑ Kohlschütter A, Schulz A, Bartsch U, Storch S (April 2019). "Current and Emerging Treatment Strategies for Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses". CNS Drugs. 33 (4): 315–325. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00620-8. PMC 6440934. PMID 30877620.

- ↑ Guhaniyogi J, Sohar I, Das K, Stock AM, Lobel P (February 2009). "Crystal structure and autoactivation pathway of the precursor form of human tripeptidyl-peptidase 1, the enzyme deficient in late infantile ceroid lipofuscinosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (6): 3985–97. doi:10.1074/jbc.M806943200. PMC 2635056. PMID 19038967.

- ↑ Mole SE, Cotman SL (October 2015). "Genetics of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (Batten disease)". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. Current Research on the Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinoses (Batten Disease). 1852 (10 Pt B): 2237–41. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.05.011. PMC 4567481. PMID 26026925.

- ↑ Sleat DE, Donnelly RJ, Lackland H, Liu CG, Sohar I, Pullarkat RK, Lobel P (September 1997). "Association of mutations in a lysosomal protein with classical late-infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis". Science. 277 (5333): 1802–5. doi:10.1126/science.277.5333.1802. PMID 9295267.

- ↑ Gardner E, Bailey M, Schulz A, Aristorena M, Miller N, Mole SE (November 2019). "Mutation update: Review of TPP1 gene variants associated with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis CLN2 disease". Human Mutation. 40 (11): 1924–1938. doi:10.1002/humu.23860. PMC 6851559. PMID 31283065.

- ↑ "Cerliponase alfa (Brineura) – Ceroid lipofuscinosis 2 (CLN2 disease)". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ↑ Mole SE, Anderson G, Band HA, Berkovic SF, Cooper JD, Kleine Holthaus SM, et al. (January 2019). "Clinical challenges and future therapeutic approaches for neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis". The Lancet. Neurology. 18 (1): 107–116. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30368-5. PMID 30470609. S2CID 53711337. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ↑ "European Commission Approves Brineura (cerliponase alfa), the First Treatment for CLN2 Disease, a Form of Batten Disease and Ultra-Rare Brain Disorder in Children". BioMarin. 1 June 2017. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ↑ "Evaluation consultation document: Cerliponase alfa for treating neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2". NICE. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ McKee S (13 February 2018). "NICE deems Batten disease therapy too costly for NHS use". Pharma Times. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ "FDA Approves BioMarin's Batten Disease Drug. Cost Per Year is $702,000". ChemDiv. 1 May 2017. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Drug Trials Snapshot: Brineura". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ New Drug Therapy Approvals 2017 (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Report). January 2018. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Cerliponase alfa". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2021.