Nalbuphine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nubain, Nalpain, Nalbuphin, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Opioid[1] |

| Main uses | Pain[1] |

| Side effects | Sleepiness, sweatiness, nausea, dizziness, dry mouth, headache[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous |

| Onset of action | • Oral: <1 hour[3] • Rectal: <30 minutes[3] • IV: 2–3 min[1] • IM: <15 minutes[1] • SC: <15 minutes[1] |

| Duration of action | 3–4 hours[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| US NLM | Nalbuphine |

| MedlinePlus | a682668 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | • Oral: 11% (young adults), >44% (elderly)[3] • IM: 81% (10 mg), 83% (20 mg) • SC: 76% (20 mg), 79% (10 mg)[5] |

| Protein binding | 50%[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver (glucuronidation)[6][3] |

| Metabolites | Glucuronide conjugates (inactive), others[7][6][3] |

| Elimination half-life | ~5 hours (3–6 hours)<[7] |

| Excretion | Urine, bile, feces;[3] 93% within 6 hours[8] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

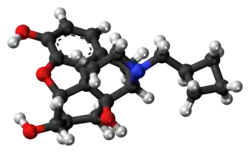

| Formula | C21H27NO4 |

| Molar mass | 357.450 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Nalbuphine, sold under the brand names Nubain among others, is an opioid which is used to treat moderate to severe pain.[1] It is given by injection into a vein, muscle, or under the skin.[1] When given by injection onset of effects is within 15 minutes and lasts for about 3 to 4 hours.[1][4]

Common side effects include sleepiness, sweatiness, nausea, dizziness, dry mouth, and headache.[2] While it causes some respiratory depression at low doses this does not increase significantly with larger doses.[7] Other side effects may include abuse and anaphylaxis.[2] It is an opioid of the partial agonist type.[2]

Nalbuphine was patented in 1963 and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1979.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[2] In the United States it costs about 4 USD per 10 mg dose as of 2021.[10] It is marketed in many countries.[11] It is not a controlled substance in the United States.[7]

Medical uses

Nalbuphine is indicated for the relief of moderate to severe pain. It can also be used as a supplement to balanced anesthesia, for preoperative and postoperative analgesia, and for obstetrical analgesia during labor and delivery. However, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that from the included studies, there was limited evidence to demonstrate that "0.1 to 0.3mg/kg nalbuphine compared to placebo might be an effective postoperative analgesic" for pain treatment in children.[12] Further research is therefore needed to compare nalbuphine with other postoperative opioids.[12]

Although nalbuphine possesses opioid antagonist activity, there is evidence that in nondependent patients it will not antagonize an opioid analgesic administered just before, concurrently, or just after an injection. Therefore, patients receiving an opioid analgesic, general anesthetics, phenothiazines, or other tranquilizers, sedatives, hypnotics, or other CNS depressants (including alcohol) concomitantly with Nalbuphine may exhibit an additive effect. When such combined therapy is contemplated, the dose of one or both agents should be reduced.

In addition to the relief of pain, the drug has been studied as a treatment for morphine induced pruritus (itching). Pruritus is a common side effect of morphine or other pure MOR agonist opioid administration. Kjellberg et al. (2001) published a review of clinical trials relating to the prevalence of morphine induced pruritus and its pharmacologic control. The authors state that nalbuphine is an effective anti-pruritic agent against morphine induced pruritus. The effect may be mediated via central nervous system mechanisms.

Pan (1998) summarizes the evidence that activation at the pharmacological level of the KOR antagonizes various MOR-mediated actions in the brain. The author states that the neural mechanism for this potentially very general MOR-antagonizing function by the KOR may have broad applications in the treatment of central nervous system mediated diseases. He does not state, however, that nalbuphine's pharmacological mechanism of action for pruritus is the result of this interaction between the two opioid receptors.

Morphine induced pruritus syndrome may also be caused by release of histamine from mast cells in the skin (Gunion et al. (2004). Paus et al. (2006) report that MORs and KORs are located in skin nerves and keratinocytes. Levy et al. (1989) reviewed the literature on the relationship of opioid mediated histamine release from cutaneous mast cells to the etiology of hypotension, flushing and pruritus. The authors investigated the relative abilities of various opioids to induce histamine release mediated increased capillary permeability and tissue edema (“wheal response” ) and cutaneous vasodilatation and local redness (“flare response”) when subjects were intradermally injected with 0.02 ml equimolar concentrations of 5 x 10-4 M. Nalbuphine did not produce either a wheal or flare response.

Dosage

The typical dose is 10 mg every 3 t 6 hours, though doses of 20 mg may be used.[1]

Nalbuphine is available in two concentrations, 10 mg and 20 mg of nalbuphine hydrochloride per mL. Both strengths contain 0.94% sodium citrate hydrous, 1.26% citric acid anhydrous, 0.1% sodium metabisulfite, and 0.2% of a 9:1 mixture of methylparaben and propylparaben as preservatives; pH is adjusted, if necessary, with hydrochloric acid. The 10 mg/mL strength contains 0.1% sodium chloride. The drug is also available in a sulfite and paraben-free formulation in two concentrations, 10 mg and 20 mg of nalbuphine hydrochloride per mL. One mL of each strength contains 0.94% sodium citrate hydrous, 1.26% citric acid anhydrous; pH is adjusted, if necessary, with hydrochloric acid. The 10 mg/mL strength contains 0.2% sodium chloride.

Side effects

Like pure MOR agonists, the mixed agonist/antagonist opioid class of drugs can cause side effects with initial administration of the drug which lessens over time (“tolerance”). This is particularly true for the side effects of nausea, sedation and cognitive symptoms (Jovey et al. 2003). These side effects can in many instances be ameliorated or avoided at the time of drug initiation by titrating the drug from a tolerable starting dose up to the desired therapeutic dose. An important difference between nalbuphine and the pure MOR agonist opioid analgesic drugs is the “ceiling effect” on respiration (but no ceiling on the analgesic effect). Respiratory depression is a potentially fatal side effect from the use of pure MOR agonists. Nalbuphine has limited ability to depress respiratory function (Gal et al. 1982).

As reported in the current Nubain Package Insert (2005), the most frequent side effect in 1066 patients treated with nalbuphine was sedation in 381 (36%).

Other, less frequent reactions are: feeling sweaty/clammy 99 (9%), nausea/vomiting 68 (6%), dizziness/vertigo 58 (5%), dry mouth 44 (4%), and headache 27 (3%). Other adverse reactions which may occur (reported incidence of 1% or less) are:

- CNS effects: Nervousness, depression, restlessness, crying, euphoria, flushing, hostility, unusual dreams, confusion, faintness, hallucinations, dysphoria, feeling of heaviness, numbness, tingling, unreality. The incidence of psychotomimetic effects, such as unreality, depersonalization, delusions, dysphoria and hallucinations has been shown to be less than that which occurs with pentazocine.

- Cardiovascular: Hypertension, hypotension, bradycardia, tachycardia, pulmonary edema.

- Gastrointestinal: Cramps, dyspepsia, bitter taste.

- Respiration: Depression, dyspnea, asthma.

- Dermatological: Itching, burning, urticaria.

- Obstetric: Pseudo-sinusoidal fetal heart rhythm.

Other possible, but rare side effects include speech difficulty, urinary urgency, blurred vision, flushing and warmth.

A 2014 Cochrane review concluded that due to limited data, analysis of adverse events for children treated with nalbuphine compared to other opioids or placebo for postoperative pain, could not be definitively reported.[12]

Overdose

In case of overdose or adverse reaction, the immediate intravenous administration of naloxone (Narcan) is a specific antidote. Oxygen, intravenous fluids, vasopressors and other supportive measures should be used as indicated.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki | EC50 | IA | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | 0.89 nM | 14 nM | 47% | [13] |

| DOR | 240 nM | ND | ND | [13] |

| KOR | 2.2 nM | 27 nM | 81% | [13] |

Nalbuphine is a semisynthetic mixed agonist/antagonist opioid modulator of the phenanthrene or morphinan series. It is structurally related to the widely used opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone, and to the potent opioid analgesic oxymorphone. Nalbuphine binds with high affinity to the MOR and KOR,[13] and has relatively low affinity for the DOR.[13] It behaves as a moderate-efficacy partial agonist (or mixed agonist/antagonist) of the MOR and as a high-efficacy partial agonist of the KOR.[13] Nalbuphine has weak or no affinity for the sigma receptor(s) (e.g., Ki > 100,000 nM).[14][15][16]

Nalbuphine is said to be more morphine-like at lower doses. However at higher doses, it produces more sedation, drunkenness, dysphoria, and dissociation.[17] As such, its effects are dose-dependent.[18] Such effects include sedation (21–36%), dizziness or vertigo (5%), lightheadedness (1%), anxiety (<1%), dysphoria (<1%), euphoria (<1%), confusion (<1%), hallucinations (<1%), depersonalization (1%), unusual dreams (<1%), and feelings of "unreality" (<1%).[18]

Nalbuphine is a potent analgesic. Its analgesic potency is essentially equivalent to that of morphine on a milligram basis, which is based on relative potency studies using intramuscular administration (Beaver et al. 1978). Oral administered nalbuphine is reported to be three times more potent than codeine (Okun et al. 1982). Clinical trials studied single dose experimental oral immediate release nalbuphine tablets for analgesic efficacy over a four- to six-hour time period following administration. Nalbuphine in the 15 to 60 mg range had similar analgesic effects to immediate release codeine in the 30 to 60 mg range (Kantor et al. 1984; Sunshine et al. 1983). Schmidt et al. (1985) reviewed the preclinical pharmacology of nalbuphine and reported comparative data relative to other types of opioid compounds. The authors point out that the nalbuphine moiety is approximately ten times more pharmacologically potent than the mixed opioid agonist/antagonist butorphanol on an "antagonist index" scale which quantitates the drug's ability to act both as an analgesic (via opioid KOR agonism) as well as a MOR antagonist. The opioid antagonist activity of nalbuphine is one-fourth as potent as nalorphine and 10 times that of pentazocine.

Pharmacokinetics

The onset of action of nalbuphine occurs within 2 to 3 minutes after intravenous administration, and in less than 15 minutes following subcutaneous or intramuscular injection. The elimination half-life of nalbuphine is approximately 5 hours on average and in clinical studies the duration of analgesic activity has been reported to range from 3 to 6 hours.

History

Nalbuphine was first synthesized in 1965 and was introduced for medical use in the United States in 1979.[19]

In the search for opioid analgesics with less abuse potential than pure MOR agonist opioids, a number of semisynthetic opioids were developed. These substances are referred to as mixed agonist–antagonists analgesics. Nalbuphine belongs to this group of substances. The mixed agonists-antagonists drug class exerts their analgesic actions by agonistic activity at the KOR. While all drugs in this class possess MOR antagonistic activity leading to less abuse potential, nalbuphine is the only approved drug in the mixed agonist-antagonist class listed in terms of its pharmacological actions and selectivities on opioid receptors as a MOR partial agonist or antagonist as well as a KOR agonist (Gustein et al. 2001).

Nubain was approved for marketing in the United States in 1978 and remains as the only opioid analgesic of this type (marketed in the U.S.) not controlled under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). When the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was enacted in 1971, nalbuphine was placed in schedule II. Endo Laboratories, Inc. subsequently petitioned the DEA to exclude nalbuphine from all schedules of the CSA in 1973. After receiving a medical and scientific review and a scheduling recommendation from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, forerunner to the Department of Health and Human Services, nalbuphine was removed from schedule II of the CSA in 1976. Presently, nalbuphine is not a controlled substance under the CSA.

Nalbuphine HCL is currently available only as an injectable in the US and the European Union. Nubain, the Astra USA brand name for injectable nalbuphine HCL, was discontinued from being marketed in 2008 in the United States for commercial reasons (Federal Register 2008); however, other commercial suppliers now provide generic injection formulation nalbuphine for the market.

Society and culture

Brand names

Nalbuphine is marketed primarily under the brand names Nubain, Nalpain, and Nalbuphin.[11] It is also marketed under the brand name Nalufin in Egypt and Raltrox in Bangladesh by Opsonin Pharma Limited, under the brand name Rubuphine in India by Rusan Healthcare Pvt Ltd, under the brand name Kinz and Nalbin in Pakistan by Sami and Global Pharmaceuticals, under the brand name Analin by Medicaids in Pakistan, and under the brand name Exnal by Indus Pharma in Pakistan, among many others.[11]

Legal status

Unlike many other opioids, nalbuphine has a limited potential for euphoria, and in accordance, is rarely abused.[7][18] This is because whereas MOR agonists produce euphoria, MOR antagonists do not, and KOR agonists like nalbuphine moreover actually produce dysphoria.[7][17] Nalbuphine was initially designated as a Schedule II controlled substance in the United States along with other opioids upon the introduction of the 1970 Controlled Substances Act.[7] However, its manufacturer, Endo Laboratories, Inc., petitioned the Food and Drug Administration to remove it from Schedule II in 1973, and after a medical and scientific review, nalbuphine was removed completely from the Controlled Substances Act in 1976 and is not a controlled substance in the United States today.[7][17] For comparison, MOR full agonists are all Schedule II in the United States, whereas the mixed KOR and MOR agonists/antagonists butorphanol and pentazocine are Schedule IV in the United States.[17] In Canada, most opioids are classified as Schedule I, but nalbuphine and butorphanol are both listed as Schedule IV substances.[20]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Howard S. Smith; Marco Pappagallo (6 September 2012). Essential Pain Pharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Cambridge University Press. pp. 343–. ISBN 978-0-521-75910-6. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Nalbuphine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bruno Bissonnette (14 May 2014). Pediatric Anesthesia. PMPH-USA. pp. 398–. ISBN 978-1-60795-213-8. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- 1 2 Greaves, Ian; Porter, Keith; Smith, Jason (7 June 2016). Practical Prehospital Care E-book: The Principles and Practice of Immediate Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-7020-4896-8. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ Excerpta medica. Section 24: Anesthesiology. 1988. Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

The mean absolute bioavailability was 81% and 83% for the 10 and 20 mg intramuscular doses, respectively, and 79% and 76% following 10 and 20 mg of subcutaneous nalbuphine.

- 1 2 Steven D. Waldman (9 June 2011). Pain Management E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 910–. ISBN 978-1-4377-3603-8. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Narver HL (March 2015). "Nalbuphine, a non-controlled opioid analgesic, and its potential use in research mice". Lab Anim (NY). 44 (3): 106–10. doi:10.1038/laban.701. PMID 25693108. S2CID 25378355.

- ↑ Yoo YC, Chung HS, Kim IS, Jin WT, Kim MK (Mar–Apr 1995). "Determination of Nalbuphine in Drug Abusers' Urine". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 19 (2): 120–123. doi:10.1093/jat/19.2.120. PMID 7769781.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 528. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- ↑ "Nalbuphine Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Nalbuphine". Archived from the original on 2018-06-18. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- 1 2 3 Schnabel, Alexander; Reichl, Sylvia U.; Zahn, Peter K.; Pogatzki-Zahn, Esther (2014-07-31). "Nalbuphine for postoperative pain treatment in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD009583. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009583.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25079857.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Peng, Xuemei; Knapp, Brian I.; Bidlack, Jean M.; Neumeyer, John L. (2007). "Pharmacological Properties of Bivalent Ligands Containing Butorphan Linked to Nalbuphine, Naltrexone, and Naloxone at μ, δ, and κ Opioid Receptors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 50 (9): 2254–2258. doi:10.1021/jm061327z. ISSN 0022-2623. PMC 3357624. PMID 17407276.

- ↑ Schmidt WK, Tam SW, Shotzberger GS, Smith DH, Clark R, Vernier VG (February 1985). "Nalbuphine". Drug Alcohol Depend. 14 (3–4): 339–62. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(85)90066-3. PMID 2986929.

- ↑ Chen JC, Smith ER, Cahill M, Cohen R, Fishman JB (1993). "The opioid receptor binding of dezocine, morphine, fentanyl, butorphanol and nalbuphine". Life Sci. 52 (4): 389–96. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(93)90152-s. PMID 8093631.

- ↑ Walker JM, Bowen WD, Walker FO, Matsumoto RR, De Costa B, Rice KC (December 1990). "Sigma receptors: biology and function". Pharmacol. Rev. 42 (4): 355–402. PMID 1964225.

- 1 2 3 4 Suzanne Nielsen; Raimondo Bruno; Susan Schenk (11 August 2017). Non-medical and illicit use of psychoactive drugs. Springer. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-3-319-60016-1. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 Thomas Markham Brown; Alan Stoudemire (1998). Psychiatric Side Effects of Prescription and Over-the-counter Medications: Recognition and Management. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-0-88048-868-6. Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- ↑ Stanley F. Malamed (23 June 2009). Sedation - E-Book: A Guide to Patient Management. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 336–. ISBN 978-0-323-07596-1. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ↑ Tara L. Bruno; Rick Csiernik (26 April 2018). The Drug Paradox: An Introduction to the Sociology of Psychoactive Substances in Canada. Canadian Scholars. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-1-77338-052-0. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|