Naloxone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Narcan, Evzio, Nyxoid, others |

| Other names | EN-1530; N-Allylnoroxymorphone; 17-Allyl-4,5α-epoxy-3,14-dihydroxymorphinan-6-one, naloxone hydrochloride (USAN US) |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Opioid receptor antagonist[1][2] |

| Main uses | Reversal of opioids[3] |

| Side effects | Opioid withdrawal (restlessness, agitation, nausea, fast heart rate, sweating)[4] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | Endotracheal, intranasal, IV, IM, IO |

| Onset of action | 2 min (IV), 5 min (IM)[4] |

| Duration of action | 30–60 min[4] |

| Defined daily dose | Not defined[6] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| US NLM | Naloxone |

| MedlinePlus | a612022 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 2% (by mouth, 90% absorption but high first-pass metabolism) 50% (intranasally) |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1–1.5 h |

| Excretion | Urine, bile |

| Chemical and physical data | |

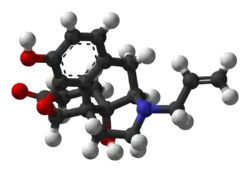

| Formula | C19H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 327.380 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Naloxone, sold under the brand name Narcan among others, is a medication used to block the effects of opioids.[4] It is commonly used to counter decreased breathing in opioid overdose.[4] Naloxone may also be combined with an opioid (in the same pill), to decrease the risk of opioid misuse.[4] When given intravenously, effects begin within two minutes, and when injected into a muscle within five minutes.[4] Another route it can be given is by spraying it into a person's nose.[9] The effects of naloxone last from about half an hour to an hour.[10] Multiple doses may be required, as the duration of action of most opioids is greater than that of naloxone.[4]

Administration to opioid-dependent individuals may cause symptoms of opioid withdrawal, including restlessness, agitation, nausea, vomiting, a fast heart rate, and sweating.[4] To prevent this, small doses every few minutes can be given until the desired effect is reached.[4] In those with previous heart disease or taking medications that negatively affect the heart, further heart problems have occurred.[4] It appears to be safe in pregnancy, after having been given to a limited number of women.[11] Naloxone is a non-selective and competitive opioid receptor antagonist.[1][2] It works by reversing the depression of the central nervous system and respiratory system caused by opioids.[4]

Naloxone was patented in 1961 and approved for opioid overdose in the United States in 1971.[12][13] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[14] Naloxone is available as a generic medication.[4] Its wholesale price in developing countries is between $0.50 and $5.30 per dose.[15] Vials of naloxone are not very expensive (less than $25) in the United States.[16] As of 2020, the price for a package of two auto-injectors in the US is $178.[17][18][19] The 2018 price for the NHS in the United Kingdom is about £5 per dose.[20] In Australia, a single dose is available, without prescription, and costs AU$20; those with a prescription, five doses can bought for AU$40, amounting to a rate of eight dollars per dose.[21]

Medical uses

Opioid overdose

Naloxone is useful in treating both acute opioid overdose and respiratory or mental depression due to opioids.[4] Whether it is useful in those in cardiac arrest due to an opioid overdose is unclear.[22]

It is included as a part of emergency overdose response kits distributed to heroin and other opioid drug users and emergency responders. This has been shown to reduce rates of deaths due to overdose.[23] A prescription for naloxone is recommended if a person is on a high dose of opioid (>100 mg of morphine equivalence/day), is prescribed any dose of opioid accompanied by a benzodiazepine, or is suspected or known to use opioids nonmedically.[24] Prescribing naloxone should be accompanied by standard education that includes preventing, identifying, and responding to an overdose; rescue breathing; and calling emergency services.[25]

If minimal or no response is observed within 2–3 minutes, dosing may be repeated every 2 minutes until the maximum dose of 10 mg has been reached. If no response occurs at this time, alternative diagnosis and treatment should be pursued. Depending on the severity of overdose, a high dose exceeding 10 mg may be needed.[26] The effects of naloxone may wear off before those of the opioids, and they may require repeat dosing at a later time. Patients experiencing effects should be monitored for respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, ABGs and level of consciousness. Those with a greater risk for respiratory depression should be identified prior to administration and watched closely.[27]

For people 65 years and older, unclear if there is a difference in response. However, older people often have decreased liver and kidney function that may lead to an increased level of naloxone in their body.[28]

Clonidine overdose

Naloxone can also be used as an antidote in overdose of clonidine, a medication that lowers blood pressure.[29] Clonidine overdoses are of special relevance for children, in whom even small doses can cause significant harm.[30] However, there is controversy regarding naloxone's efficacy in treating the symptoms of clonidine overdose, namely slow heart rate, low blood pressure, and confusion/somnolence.[30] Case reports that used doses of 0.1 mg/kg (maximum of 2 mg/dose) repeated every 1–2 minutes (10 mg total dose) have shown inconsistent benefit.[30] As the doses used throughout the literature vary, it is difficult to form a conclusion regarding the benefit of naloxone in this setting.[31] The mechanism for naloxone's proposed benefit in clonidine overdose is unclear, but it has been suggested that endogenous opioid receptors mediate the sympathetic nervous system in the brain and elsewhere in the body.[31] Some poison control centers recommend naloxone in the setting of clonidine overdose, including intravenous bolus doses of up to 10 mg naloxone.[32][33]

Preventing opioid abuse

Naloxone is poorly absorbed when taken by mouth, so it is commonly combined with a number of oral opioid preparations, including buprenorphine and pentazocine, so that when taken by mouth, only the opioid has an effect.[4][34] However, if the opioid and naloxone combination is injected, the naloxone blocks the effect of the opioid.[4][34] This combination is used in an effort to prevent abuse.[34]

Other uses

In people with shock, including septic, cardiogenic, hemorrhagic, or spinal shock, those who received naloxone had improved blood flow. The importance of this is unclear.[35]

Naloxone is also experimentally used in the treatment for congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis,[36] an extremely rare disorder that renders one unable to feel pain or differentiate temperatures.[37]

Naloxone can also be used to treat itchiness brought on by opioid use,[38] as well as opioid-induced constipation.[39]

Children

Naloxone can be used in babies who were exposed to intrauterine opiates administered to mothers during delivery. However, there is insufficient evidence for the use of naloxone to lower cardiorespiratory and neurological depression in these infants.[40] Infants exposed to high concentrations of opiates during pregnancy may have CNS damage in the setting of perinatal asphyxia. Naloxone has been studied to improve outcomes in this population, however the evidence is currently weak.[41][42]

Intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous administration of naloxone can be given to children and neonates to reverse opiate effects. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends only intravenous administration as the other two forms can cause unpredictable absorption. After a dose is given, the child should be monitored for at least 24 hours. For children with low blood pressure due to septic shock, naloxone safety and effectiveness is not established.[43]

Dosage

In adults the typical dose is 1 to 3 micrograms per kg (0.2 mg) intravenously.[3] In children 5 to 10 micrograms per kg intravenously may be used.[3] If after 2 to 3 minutes there is insufficient benefit the dose may be repeated.[3]

The intravenous route is preferred over the IM route.[3] The defined daily dose is not defined.[6]

Side effects

Naloxone has little to no effect if opioids are not present. In people with opioids in their system, it may cause increased sweating, nausea, restlessness, trembling, vomiting, flushing, and headache, and has in rare cases been associated with heart rhythm changes, seizures, and pulmonary edema.[44][45]

Besides the side effects listed above, naloxone also has other adverse events, such as other cardiovascular effects (hypertension, hypotension, tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia) and central nervous system effects, such as agitation, body pain, brain disease, and coma. In addition to these adverse effects, naloxone is also contraindicated in people with hypersensitivity to naloxone or any of its formulation components.[46]

Naloxone has been shown to block the action of pain-lowering endorphins the body produces naturally. These endorphins likely operate on the same opioid receptors that naloxone blocks. It is capable of blocking a placebo pain-lowering response, if the placebo is administered together with a hidden or blind injection of naloxone.[47] Other studies have found that placebo alone can activate the body's μ-opioid endorphin system, delivering pain relief by the same receptor mechanism as morphine.[48][49]

Naloxone should be used with caution in people with cardiovascular disease as well as those that are currently taking medications that could have adverse effects on the cardiovascular system such as causing low blood pressure, fluid accumulation in the lungs (pulmonary edema), and abnormal heart rhythms. There have been reports of abrupt reversals with opioid antagonists leading to pulmonary edema and ventricular fibrillation.[50]

Hypersensitivities

Naloxone preparations may contain methylparaben and propylparaben and is inappropriate for use by people with a paraben hypersensitivity. If a person is sensitive to nalmefene or naltrexone, naloxone should be used with caution as these three medications are structurally similar. Cross-sensitivity among these drugs is unknown.[51] Preservative-free preparations are available for those with paraben hypersensitivities.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Naloxone is pregnancy category B or C in the United States.[4] Risks of untreated insufficient breathing; however, are likely greater than the risks of naloxone.[52]

Studies in rodents given a daily maximum dose of 10 mg naloxone showed no harmful effects to the fetus, although human studies are lacking and the drug does cross the placenta, which may lead to the precipitation of withdrawal in the fetus. In this setting, further research is needed before safety can be assured, so naloxone should be used during pregnancy only if it is a medical necessity.[53]

Whether naloxone is excreted in breast milk is unknown, however, it is not active when taken by mouth and therefore is unlikely to affect a breastfeeding infant.[54]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Compound | Affinities (Ki) | Ratio | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | DOR | KOR | MOR:DOR:KOR | ||

| Naloxone | 1.1 nM | 16 nM | 12 nM | 1:15:11 | [55] |

| (−)-Naloxone | 0.559 nM 0.93 nM | 36.5 nM 17 nM | 4.91 nM 2.3 nM | 1:65:9 1:18:2 | [56] [57] |

| (+)-Naloxone | 3,550 nM 1,000 nM | 122,000 nM 1,000 nM | 8,950 nM 1,000 nM | 1:34:3 ND | [56] [57] |

Naloxone is a lipophilic compound that acts as a non-selective and competitive opioid receptor antagonist.[1][2] The pharmacologically active isomer of naloxone is (−)-naloxone.[56][58] Naloxone's binding affinity is highest for the μ-opioid receptor, then the δ-opioid receptor, and lowest for the κ-opioid receptor;[1] naloxone has negligible affinity for the nociceptin receptor.[59]

If naloxone is administered in the absence of concomitant opioid use, no functional pharmacological activity occurs, except the inability for the body to combat pain naturally. In contrast to direct opiate agonists, which elicit opiate withdrawal symptoms when discontinued in opiate-tolerant people, no evidence indicates the development of tolerance or dependence on naloxone. The mechanism of action is not completely understood, but studies suggest it functions to produce withdrawal symptoms by competing for opiate receptor sites within the CNS (a competitive antagonist, not a direct agonist), thereby preventing the action of both endogenous and xenobiotic opiates on these receptors without directly producing any effects itself.[60]

Pharmacokinetics

When administered parenterally (nonorally or nonrectally, e.g. intravenously or by injection), as is most common, naloxone has a rapid distribution throughout the body. The mean serum half life has been shown to range from 30 to 81 minutes, shorter than the average half life of some opiates, necessitating repeat dosing if opioid receptors must be stopped from triggering for an extended period. Naloxone is primarily metabolized by the liver. Its major metabolite is naloxone-3-glucuronide, which is excreted in the urine.[60] For people with liver diseases such as alcoholic liver disease or hepatitis, naloxone usage has not been shown to increase serum liver enzyme levels.[61]

Naloxone has low systemic bioavailability when taken by mouth due to hepatic first pass metabolism, but it does block opioid receptors that are located in the intestine.[39]

Chemistry

Naloxone, also known as N-allylnoroxymorphone or as 17-allyl-4,5α-epoxy-3,14-dihydroxymorphinan-6-one, is a synthetic morphinan derivative and was derived from oxymorphone (14-hydroxydihydromorphinone), an opioid analgesic.[62][63][64] Oxymorphone, in turn, was derived from morphine, an opioid analgesic and naturally occurring constituent of the opium poppy.[65] Naloxone is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, (–)-naloxone (levonaloxone) and (+)-naloxone (dextronaloxone), only the former of which is active at opioid receptors.[66][67] The drug is a highly lipophilic, allowing it to rapidly penetrate the brain and to achieve a far greater brain to serum ratio than that of morphine.[62] Opioid antagonists related to naloxone include cyprodime, nalmefene, nalodeine, naloxol, and naltrexone.[68]

The chemical half-life of naloxone is such that injection and nasal forms have been marketed with 24-month and 18-month shelf-lives, respectively.[69] A 2018 study noted that the nasal and injection forms presented as chemically stable to 36- and 28-months, respectively, which prompted an as yet incomplete five year stability study to be initiated.[69] This suggests that expired caches of material in community and healthcare settings may still be efficacious substantially beyond their labeled expiration dates.[69]

History

Naloxone was patented in 1961 by Mozes J. Lewenstein, Jack Fishman, and the company Sankyo.[12] It was approved for opioid abuse treatment in the United States in 1971,[70] with opioid abuse kits being distributed by many states to medically untrained people beginning in 1996. From the period of 1996 to 2014, the CDC estimates over 26,000 cases of opioid overdose have been reversed using the kits.[71]

Naloxone (Nyxoid) was approved for use in the European Union in September 2017.[72]

Society and culture

Names

Naloxone is the generic name of the medication and its INN, BAN, DCF, DCIT, and JAN, while naloxone hydrochloride is its USAN and BANM.[73][74][75][76]

The patent has expired and it is available as a generic medication. Brand names of naloxone include Narcan, Nalone, Evzio, Prenoxad Injection, Narcanti, Narcotan, among others.

Identification

The CAS number of naloxone is 465-65-6; the anhydrous hydrochloride salt has CAS 357-08-4 and the hydrochloride salt with 2 molecules of water, hydrochloride dihydrate, has CAS 51481-60-8

Routes of administration

Intravenous

Naloxone is commonly injected intravenously, with an onset of 1–2 minutes and a duration of up to 45 minutes.[77] While the onset is achieved fastest through IV than through other routes of administration, it may be difficult to obtain venous access in patients who use IV drugs chronically. This may be an issue under emergency conditions.[78]

Intramuscular or subcutaneous

Naloxone can also be administered via intramuscular or subcutaneous injection. The onset of naloxone provided through this route is 2 to 5 minutes with a duration of around 30-120min.[79] Naloxone administered intramuscularly are provided through pre-filled syringes, vials, and auto-injector. Evzio is the only auto-injector on the market and can be used both intramuscularly and subcutaneously. It is pocket-sized and can be used in non-medical settings such as in the home.[22] It is designed for use by laypersons, including family members and caregivers of opioid users at-risk for an opioid emergency, such as an overdose.[80] According to the FDA's National Drug Code Directory, a generic version of the auto-injector began to be marketed at the end of 2019.[18]

Intranasal

Administration of naloxone intranasally is recommended for people who are unconscious or unresponsive.[79] While the onset of action is slightly delayed in this method of administration, the ease of use and portability are what make naloxone nasal sprays useful.[77][79] Narcan Nasal Spray was approved in 2015 and was the first FDA-approved nasal spray for emergency treatment or suspected overdose.[81] Narcan Nasal Spray is prepackaged, requires no assembly, and delivered a consistent dose.[82] It was developed in a partnership between LightLake Therapeutics and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.[83] The approval process was fast-tracked.[84] A generic version of the nasal spray was approved in the United States in 2019.[85]

However, a wedge device (nasal atomizer) can also be attached to a syringe that may also be used to create a mist to deliver the drug to the nasal mucosa.[86] This is useful near facilities where many overdoses occur that already stock injectors.[87]

Storage

Naloxone should be stored at room temperature and protected from light. For the auto-injector, naloxone should be stored in the outer case provided.[88] If the product is cloudy, discolored, or contains particulate matter, use is not recommended.[51]

Labeling

The opioid crisis in the US points out the necessity for an increase in the availability of the opioid antagonist naloxone as administered in overdose situations. In May 2020, the FDA reported on its creation of a “model drug facts label” that would enable average consumers with little or no specific training to comprehend the major components in effective, safe administration of naloxone. The agency used two prescription products in its test: the prefilled auto-injector Evzio and the nasal spray Narcan, both approved for community use in 2016. Working with experts on addiction, FDA researchers condensed the clinical information on naloxone (6,300 words over 18 pages) to eight “primary end points” providing essential data on usage in a crisis overdose emergency. The trial consisted of interviews with 710 adolescents and adults, including 430 opioid users, along with their family and friends. Results indicated that those being interviewed sufficiently understood six of the eight primary end points, and “came close” on the remaining two. The agency concluded the model label was adequate for use on naloxone sold over the counter. FDA also reported that if individuals comprehend instructions, administer naloxone and call 911, “…many lives will be saved.” They also recommended that manufacturers highlight “Call 911” on package labels.[89]

Legal status

In the United States, naloxone is available without a prescription in every state with the exception of Hawaii.[90][91] However, not all pharmacies stock or dispense naloxone.[92][93] Depending on the pharmacy, a pharmacist may have to write a prescription or not be able to give naloxone to comply with accounting rules regarding prescription medications, as naloxone is still considered a prescription only medication under FDA rules.

While paramedics have carried naloxone for decades, law enforcement officers in many states throughout the country carry naloxone to reverse the effects of heroin overdoses when reaching the location prior to paramedics. As of July 12, 2015, law enforcement departments in 28 states are allowed to or required to carry naloxone to quickly respond to opioid overdoses.[94]

In Australia, as of February 1, 2016, some forms of naloxone are available "over the counter" in pharmacies without a prescription.[7][95][96] It comes in single-use filled syringe similar to law enforcement kits. A single dose costs AU$20; for those with a prescription, five doses can bought for AU$40, amounting to a rate of eight dollars per dose (2019).[97]

In Canada, naloxone single-use syringe kits are distributed and available at various clinics and emergency rooms. Alberta Health Services is increasing the distribution points for naloxone kits at all emergency rooms, and various pharmacies and clinics province-wide. Also in Alberta, take-home naloxone kits are available and commonly distributed in most drug treatment or rehabilitation centres, as well as in pharmacies where pharmacists can distribute single-use take-home naloxone kits or prescribe the drug to addicts. All Edmonton Police Service and Calgary Police Service patrol cars carry an emergency single-use naloxone syringe kit. Some Royal Canadian Mounted Police patrol vehicles also carry the drug, occasionally in excess to help distribute naloxone among users and concerned family/friends. Nurses, paramedics, medical technicians, and emergency medical responders can also prescribe and distribute the drug.

Following Alberta Health Services, Health Canada reviewed the prescription-only status of naloxone, resulting in plans to remove it in 2016, allowing naloxone to be more accessible.[98][99] Due to the rising number of drug deaths across the country, Health Canada proposed a change to make naloxone more widely available to Canadians in support of efforts to address the growing number of opioid overdoses.[100] In March 2016, Health Canada did change the prescription status of naloxone, as "pharmacies are now able to proactively give out naloxone to those who might experience or witness an opioid overdose."[101]

Prehospital access

Laws in many jurisdictions have been changed in recent years to allow wider distribution of naloxone.[102][103] Several states have also moved to permit pharmacies to dispense the medication without the person first seeing a physician or other non-pharmacist professional.[104] Over 200 naloxone distribution programs utilize licensed prescribers to distribute the drug, often through the use of standing medication orders [105][106] whereby the medication is distributed under the medical authority of a physician or other prescriber (such as a pharmacist under California's AB1535). Additionally, 36 states have passed laws that provide naloxone prescribers with immunity against both civil and criminal liabilities.[107] Third-party prescriptions are also available for people, such as family and friends of people at risk for an overdose, who may find themselves in a situation that requires them to administer naloxone. Local schools, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations hold training programs to educate laypeople on proper use of naloxone. It is estimated that programs like these have helped to reverse more than 26,000 overdoses.[107]

Following the use of the nasal spray device by police officers on Staten Island in New York, an additional 20,000 police officers will begin carrying naloxone in mid-2014. The state's Office of the Attorney General will provide US$1.2 million to supply nearly 20,000 kits. Police Commissioner William Bratton said: "Naloxone gives individuals a second chance to get help".[108] Emergency Medical Service Providers (EMS) routinely administer naloxone, except where basic Emergency Medical Technicians are prohibited by policy or by state law.[109] In efforts to encourage citizens to seek help for possible opioid overdoses, many states have adopted Good Samaritan laws that provide immunity against certain criminal liabilities for anybody who, in good faith, seeks emergency medical care for either themselves or someone around them who may be experiencing an opioid overdose.[110]

A survey of US naloxone prescription programs in 2010 revealed that 21 out of 48 programs reported challenges in obtaining naloxone in the months leading up to the survey, due mainly to either cost increases that outstripped allocated funding or the suppliers' inability to fill orders.[111] The approximate cost of a 1 ml ampoule of naloxone in the US is estimated to be significantly higher than in most Western countries.[105]

Projects of this type are under way in many North American cities.[111][112] CDC estimates that the US programs for drug users and their caregivers prescribing take-home doses of naloxone and training on its use have prevented 10,000 opioid overdose deaths.[111] States including Vermont and Virginia have developed programs that mandate the prescription of naloxone when a prescription has exceeded a certain level of morphine milliequivalents per day as preventative measures against overdose.[113] Healthcare institution-based naloxone prescription programs have also helped reduce rates of opioid overdose in North Carolina, and have been replicated in the US military.[105][114] Programs training police and fire personnel in opioid overdose response using naloxone have also shown promise in the US, and effort is increasing to integrate opioid fatality prevention in the overall response to the overdose crisis.[115][116][117][118]

Pilot projects were also started in Scotland in 2006. Also in the UK, in December 2008, the Welsh Assembly government announced its intention to establish demonstration sites for take-home naloxone.[119]

As of February 2016, Pharmacies across Alberta and some other Canadian jurisdictions are allowed to distribute take-home naloxone kits. Additionally, the Minister of Health issued an order to change basic life support provider's medical scope, within EMS, to administer naloxone in the event of a suspected narcotic overdose. These are part of the government's plan to tackle a growing fentanyl drug crisis.[120]

In 2018, a maker of naloxone announced it would provide a free kit including two doses of the nasal spray, as well as educational materials, to each of the 16,568 public libraries and 2,700 YMCAs in the U.S.[121]

Media

The 2013 documentary film Reach for Me: Fighting to End the American Drug Overdose Epidemic interviews people involved in naloxone programs aiming to make naloxone available to opioid users and people with chronic pain.[122]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 190–191, 287. ISBN 9780071481274.

Products of this research include the discovery of lipophilic, small-molecule opioid receptor antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, which have been critical tools for investigating the physiology and behavioral actions of opiates. ... A competitive antagonist of opiate action (naloxone) had been identified in early studies. ... Opiate antagonists have clinical utility as well. Naloxone, a nonselective antagonist with a relative affinity of μ > δ > κ, is used to treat heroin and other opiate overdoses.

- 1 2 3 "Narcan- naloxone hydrochloride spray Narcan- naloxone hydrochloride spray". DailyMed. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "NALOXONE injectable - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "Naloxone Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved Jan 2, 2015.

- 1 2 "Naloxone Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 September 2019. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- 1 2 Lenton, Simon R; Dietze, Paul M; Jauncey, Marianne (7 March 2016). "Australia reschedules naloxone for opioid overdose". The Medical Journal of Australia. 204 (4): 146–147. doi:10.5694/mja15.01181. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ "Naloxone 400 micrograms/ml solution for Injection/Infusion - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 6 February 2019. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ↑ Roberts, James R. (2014). Roberts and Hedges' clinical procedures in emergency medicine (6 ed.). London: Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 476. ISBN 9781455748594. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Bosack, Robert (2015). Anesthesia Complications in the Dental Office. John Wiley & Sons. p. 191. ISBN 9781118828625. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- 1 2 Yardley, William (14 December 2013). "Jack Fishman Dies at 83; Saved Many From Overdose". New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 2015-07-06.

- ↑ US patent 3493657, Jack Fishman & Mozes Juda Lewenstein, "Therapeutic compositions of n-allyl-14-hydroxy - dihydronormorphinane and morphine", published 1970-02-03, issued 1970-02-03, assigned to Mozes Juda Lewenstein

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Naloxone HCL". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richard J. (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia : 2014 classic shirt-pocket edition (28 ed.). Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 174. ISBN 9781284053982. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Evzio Authorized Generic Soon to Be Available". MPR. 2018-12-12. Archived from the original on 2019-10-23. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- 1 2 "NDC 72853-051-02 Naloxone Hydrochloride Auto-injector". NDClist.com. Archived from the original on 2020-03-21. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- ↑ "National Drug Code Directory". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2020-03-21.

- ↑ British national formulary : BNF 74 (74 ed.). British Medical Association. 2017. p. 1260. ISBN 978-0857112989.

- ↑ Coulter, Ellen (27 August 2019). "This drug can temporarily reverse an opioid overdose. So why aren't people using it?". ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- 1 2 Lavonas, EJ; Drennan, IR; Gabrielli, A; Heffner, AC; Hoyte, CO; Orkin, AM; Sawyer, KN; Donnino, MW (3 November 2015). "Part 10: Special Circumstances of Resuscitation: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S501-18. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000264. PMID 26472998.

- ↑ Maxwell S, Bigg D, Stanczykiewicz K, Carlberg-Racich S (2006). "Prescribing naloxone to actively injecting heroin users: a program to reduce heroin overdose deaths". J Addict Dis. 25 (3): 89–96. doi:10.1300/J069v25n03_11. PMID 16956873.

- ↑ Lazarus P (2007). "Project Lazarus, Wilkes County, North Carolina: Policy Briefing Document Prepared for the North Carolina Medical Board in Advance of the Public Hearing Regarding Prescription Naloxone". Raleigh, NC.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Bowman S, Eiserman J, Beletsky L, Stancliff S, Bruce RD (July 2013). "Reducing the health consequences of opioid addiction in primary care". Am. J. Med. 126 (7): 565–71. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.031. PMID 23664112.

- ↑ Bardsley, Russell (2019-10-30). "Higher naloxone dosing may be required for opioid overdose". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 76 (22): 1835–1837. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz208. ISSN 1535-2900. PMID 31665765.

- ↑ "Up To Date: Naloxone Monitoring Parameters". Up to Date. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Niemann, JT; Getzug, T; Murphy, W (October 1986). "Reversal of clonidine toxicity by naloxone". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 15 (10): 1229–31. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80874-5. PMID 3752658.

- 1 2 3 Ahmad, Syed A.; Scolnik, Dennis; Snehal, Vala; Glatstein, Miguel (2015). "Use of Naloxone for Clonidine Intoxication in the Pediatric Age Group". American Journal of Therapeutics. 22 (1): e14–e16. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e318293b0e8. PMID 23782760.

- 1 2 Seger, DL (2002). "Clonidine toxicity revisited". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 40 (2): 145–155. doi:10.1081/CLT-120004402. PMID 12126186.

- ↑ "Poison Alert: Clonidine" (PDF). missouripoisoncenter.org. Missouri Poison Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ↑ Loden, Justin. "Tennessee Poison Center - 03-26-18 Does naloxone reverse clonidine toxicity? - Vanderbilt Health Nashville, TN". ww2.mc.vanderbilt.edu. Tennessee Poison Center. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 1 2 3 Orman, JS; Keating, GM (2009). "Buprenorphine/naloxone: a review of its use in the treatment of opioid dependence". Drugs. 69 (5): 577–607. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969050-00006. PMID 19368419.

- ↑ Boef, B; Poirier V; Gauvin F; Guerguerian AM; Roy C; Farrell CA; Lacroix J (2003). "Naloxone for shock". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004443. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004443. PMID 14584016.

- ↑ Protheroe, SM (1991). "Congenital insensitivity to pain". J R Soc Med. 84 (9): 558–559. doi:10.1177/014107689108400918. PMC 1293421. PMID 1719200.

- ↑ Reference, Genetics Home. "CIPA". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ↑ "Naloxone". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- 1 2 Meissner W, Schmidt U, Hartmann M, Kath R, Reinhart K (January 2000). "Oral naloxone reverses opioid-associated constipation". Pain. 84 (1): 105–9. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00185-2. PMID 10601678.

- ↑ Moe-Byrne, Thirimon; Brown, Jennifer VE; McGuire, William (28 February 2013). "Naloxone for opiate-exposed newborn infants". The Cochrane Library (2): CD003483. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003483.pub2. PMID 23450541.

- ↑ McGuire, William; Fowlie, Peter W; Evans, David J (2004-01-26). "Naloxone for preventing morbidity and mortality in newborn infants of greater than 34 weeks' gestation with suspected perinatal asphyxia". The Cochrane Library. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (1): CD003955. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003955.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6485479. PMID 14974047.

- ↑ Moe-Byrne, Thirimon; Brown, Jennifer Valeska Elli; McGuire, William (12 October 2018). "Naloxone for opioid-exposed newborn infants". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD003483. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003483.pub3. PMC 6517169. PMID 30311212.

- ↑ "Narcan (Naloxone Hydrochloride Injection): Side Effects, Interactions, Warning, Dosage & Uses". RxList. Archived from the original on 2020-11-11. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- ↑ "Naloxone Side Effects in Detail". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ Schwartz JA, Koenigsberg MD (November 1987). "Naloxone-induced pulmonary edema". Ann Emerg Med. 16 (11): 1294–6. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(87)80244-5. PMID 3662194.

- ↑ "Naloxone: Drug Information". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17.

- ↑ Sauro MD, Greenberg RP (February 2005). "Endogenous opiates and the placebo effect: a meta-analytic review". J Psychosom Res. 58 (2): 115–20. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.07.001. PMID 15820838.

- ↑ "More Than Just a Sugar Pill: Why the placebo effect is real - Science in the News". Science in the News. 2016-09-14. Archived from the original on 2017-11-15. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- ↑ Carvalho, Cláudia; Caetano, Joaquim Machado; Cunha, Lidia; Rebouta, Paula; Kaptchuk, Ted J.; Kirsch, Irving (December 2016). "Open-label placebo treatment in chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial". Pain. 157 (12): 2766–2772. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000700. ISSN 1872-6623. PMC 5113234. PMID 27755279.

- ↑ "Naloxone: Contraindications". Up to Date. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- 1 2 "Narcan (naloxone hydrochloride) dose, indications, adverse effects, interactions... from PDR.net". www.pdr.net. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- ↑

- ↑ Sobor, M; Timar, J.; Riba, P.; Kiraly, KP. (2013). "Behavioural studies during the gestational-lactation period in morphine treated rats". Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 15 (4): 239–251. PMID 24380965.

- ↑ "Naloxone use while Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-02. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ↑ Tam SW (1985). "(+)-[3H]SKF 10,047, (+)-[3H]ethylketocyclazocine, mu, kappa, delta and phencyclidine binding sites in guinea pig brain membranes". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 109 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(85)90536-9. PMID 2986989.

- 1 2 3 Codd EE, Shank RP, Schupsky JJ, Raffa RB (September 1995). "Serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibiting activity of centrally acting analgesics: structural determinants and role in antinociception". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 274 (3): 1263–70. PMID 7562497. Archived from the original on 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2014-12-13.

- 1 2 Raynor K, Kong H, Chen Y, Yasuda K, Yu L, Bell GI, Reisine T (1994). "Pharmacological characterization of the cloned kappa-, delta-, and mu-opioid receptors". Mol. Pharmacol. 45 (2): 330–4. PMID 8114680. Archived from the original on 2018-06-22. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ↑ "Naloxone: Summary". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

The approved drug naloxone INN-assigned preparation is the (-)-enantiomer. ... The (+) isomer is inactive at the opioid receptors. Marketed formulations may contain naloxone hydrochloride

- ↑ "Opioid receptors: Introduction". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

The opioid antagonist, naloxone, which binds to μ, δ and κ receptors (with differing affinities), does not have significant affinity for the ORL1/LC132 receptor. These studies indicate that, from a pharmacological perspective, there are two major branches in the opioid peptide-N/OFQ receptor family: the main branch comprising the μ, δ and κ receptors, where naloxone acts as an antagonist; and a second branch with the receptor for N/OFQ, which has negligible affinity for naloxone.

- 1 2 "Naloxone Hydrochloride injection, solution". Daily Med. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ "Naloxone", LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012, PMID 31643568, archived from the original on 2021-08-28, retrieved 2019-10-30

- 1 2 Reginald Dean; Edward J. Bilsky; S. Stevens Negus (12 March 2009). Opiate Receptors and Antagonists: From Bench to Clinic. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 514–. ISBN 978-1-59745-197-0. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Hiroshi Nagase (21 January 2011). Chemistry of Opioids. Springer. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-3-642-18107-8. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ "Morphinan-6-one, 4,5-epoxy-3,14-dihydroxy-17-(2-propenyl)-, (5α)-". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ↑ Marvin D Seppala; Mark E. Rose (25 January 2011). Prescription Painkillers: History, Pharmacology, and Treatment. Hazelden Publishing. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-1-59285-993-1. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Louise A. Bennett (2006). New Topics in Substance Abuse Treatment. Nova Publishers. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-1-59454-831-4. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ↑ John Q. Wang (2003). Drugs of Abuse: Neurological Reviews and Protocols. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-1-59259-358-3. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ↑ Laurence Brunton; Bruce Chabner; Bjorn Knollman (20 December 2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 510. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 "New Study Indicates Opioid Overdose Reversal Products Chemically Stable Well Past Expiration: Extended Shelf-Life Has Potential for Stockpiles and Communities Date" (PDF) (Press release). American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists. 6 November 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ↑ "Naloxone: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ↑ "The History of Naloxone - Cordant Solutions". Cordant Solutions. 2017-07-05. Archived from the original on 2017-11-15. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- ↑ "Nyxoid EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ↑ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 851–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 715–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ↑ "Naloxone". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- 1 2 Lexicomp. (2013). Drug information handbook for advanced practice nursing : a comprehensive resource for nurse practitioners, nurse midwives and clinical specialists, including selected disease management guidelines. Lexicomp. ISBN 978-1591953234. OCLC 827841946.

- ↑ Naloxone for Treatment of Opioide Overdose Advisory 2016

- 1 2 3 Naloxone for Treatment of Opioid Overdose Oct. 2016

- ↑ FDA News Release. "FDA approves new hand-held auto-injector to reverse opioid overdose". FDA.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (2019-09-11). "FDA approves first generic naloxone nasal spray to treat opioid overdose". FDA. Archived from the original on 2019-09-14. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Narcan Nasal Spray". www.jems.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-20. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ↑ Volkow, Nora (18 November 2015). "NARCAN Nasal Spray: Life Saving Science at NIDA". DrugAbuse.gov—"Nora's Blog". Archived from the original on 2017-02-26.

- ↑ Brady Dennis (3 April 2014). "FDA approves device to combat opioid drug overdose". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (2019-04-19). "Press Announcements - FDA approves first generic naloxone nasal spray to treat opioid overdose". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-04-22. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ↑ Wolfe TR, Bernstone T (April 2004). "Intranasal drug delivery: an alternative to intravenous administration in selected emergency cases". J Emerg Nurs. 30 (2): 141–7. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2004.01.006. PMID 15039670.

- ↑ Fiore, Kristina (2015-06-13). "On-Label Nasal Naloxone in the Works". MedPage Today. Archived from the original on 2015-08-01. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

- ↑ "These highlights do not include all the information needed to use EVZIO® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for EVZIO. EVZIO® (naloxone hydrochloride injection) Auto-Injector for intramuscular or subcutaneous use 2 mg Initial U.S. Approval: 1971". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ↑ Cohen, Barbara R.; Mahoney, Karen M.; Baro, Elande; Squire, Claudia; Beck, Melissa; Travis, Sara; Pike-McCrudden, Amanda; Izem, Rima; Woodcock, Janet (2020). "FDA Initiative for Drug Facts Label for Over-the-Counter Naloxone". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (22): 2129–2136. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1912403. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ "Naloxone Opioid Overdose Reversal Medication". CVS Health. Archived from the original on 2018-09-19. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ↑ Eagle, Chrissy Suttles, Wyoming Tribune. "Wyoming's Albertsons, Safeway pharmacies to offer Narcan over the counter". Wyoming Tribune Eagle. Archived from the original on 2018-02-03. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ↑ Meyerson, B.E.; Agley, J.D.; Davis, A.; Jayawardene, W.; Hoss, A.; Shannon, D.J.; Ryder, P.T.; Ritchie, K.; Gassman, R. (July 2018). "Predicting pharmacy naloxone stocking and dispensing following a statewide standing order, Indiana 2016". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 188: 187–192. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.032. PMC 6375076. PMID 29778772.

- ↑ Meyerson, B.E.; Agley, J.D.; Jayawardene, W.; Eldridge, L.A.; Arora, P.; Smith, C.; Vadiei, N.; Kennedy, A.; Moehling, T. (August 2019). "Feasibility and acceptability of a proposed pharmacy-based harm reduction intervention to reduce opioid overdose, HIV and hepatitis C". Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 16 (5): 699–709. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.08.026. PMID 31611071.

- ↑ "US Law Enforcement Who Carry Naloxone". North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ↑ Melissa Davey (29 January 2016). "Selling opioid overdose antidote Naloxone over counter 'will save lives'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016.

- ↑ "Why the 'heroin antidote' naloxone is now available in pharmacies". ABC. 1 February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ↑ Coulter, Ellen (27 August 2019). "This drug can temporarily reverse an opioid overdose. So why aren't people using it?". ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "Naloxone's prescription-only status to get Health Canada review". CBC News. Archived from the original on 2016-02-05. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ↑ "Fentanyl and the take-home naloxone program Alberta Health". Archived from the original on 2016-02-05. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ↑ "Health Canada Statement on Change in Federal Prescription Status of Naloxone". news.gc.ca. January 14, 2016. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved February 29, 2016 – via Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers - Naloxone". Health Canada. March 22, 2017. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ↑ Corey Davis. "Legal interventions to reduce overdose mortality: Naloxone access and overdose good samaritan laws" (PDF). Network for Public Health Law. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-09-03.

- ↑ Davis CS, Webb D, Burris SC (2013). "Changing Law from Barrier to Facilitator of Opioid Overdose Prevention". Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 41: 33–36. doi:10.1111/jlme.12035. PMID 23590737.

- ↑ Ryan Oftebro, "Kelley-Ross Pharmacy provides Take-Home Naloxone to prevent opioid overdose" Archived 2014-05-19 at the Wayback Machine, Kelley-Ross, August 20, 2013

- 1 2 3 Beletsky L, Burris SC, Kral AH (2009). "Closing Death's Door: Action Steps to Facilitate Emergency Opioid Drug Overdose Reversal in the United States". doi:10.2139/ssrn.1437163.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Burris SC, Beletsky L, Castagna CA, Coyle C, Crowe C, McLaughlin JM (2009). "Stopping an Invisible Epidemic: Legal Issues in the Provision of Naloxone to Prevent Opioid Overdose". doi:10.2139/ssrn.1434381.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 "As Naloxone Accessibility Increases, Pharmacist's Role Expands". Pharmacy Times. Archived from the original on 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ↑ Jessica Durando (27 May 2014). "NYPD officers to carry heroin antidote". USA Today. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ Faul M, Dailey MW, Sugerman DE, Sasser SM, Levy B, Paulozzi LJ (2015). "Disparity in Naloxone Administration by Emergency Medical Service Providers and the Burden of Drug Overdose in US Rural Communities". American Journal of Public Health. 105: e26–e32. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302520. PMC 4455515. PMID 25905856.

- ↑ "Drug Overdose Immunity and Good Samaritan Laws". www.ncsl.org. Archived from the original on 2019-09-13. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- 1 2 3 Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (December 2010). "Community-Based Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone — United States, 2010". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 61 (6): 101–5. PMC 4378715. PMID 22337174. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26.

- ↑ Karissa Donkin (9 September 2012). "Toronto naloxone program reduces drug overdoses among addicts". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Christopher M.; Compton, Wilson; Vythilingam, Meena; Giroir, Brett (2019-08-06). "Naloxone Co-prescribing to Patients Receiving Prescription Opioids in the Medicare Part D Program, United States, 2016-2017". JAMA. 322 (5): 462–464. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.7988. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 6686765. PMID 31386124.

- ↑ Albert S, Brason FW, Sanford CK, Dasgupta N, Graham J, Lovette B (June 2011). "Project Lazarus: community-based overdose prevention in rural North Carolina". Pain Med. 12 Suppl 2: S77–85. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01128.x. PMID 21668761.

- ↑ Beletsky L, Rich JD, Walley AY (November 2012). "Prevention of fatal opioid overdose". JAMA. 308 (18): 1863–4. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.14205. PMC 3551246. PMID 23150005.

- ↑ Lavoie D (April 2012). "Naloxone: Drug-Overdose Antidote Is Put In Addicts' Hands". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2012-05-18.

- ↑ Davis CS, Beletsky L (2009). "Bundling occupational safety with harm reduction information as a feasible method for improving police receptiveness to syringe access programs: evidence from three U.S. cities". Harm Reduct J. 6 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-16. PMC 2716314. PMID 19602236.

- ↑ "2013 National drug control strategy" (PDF). 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2013.

- ↑ "IHRA 21st International Conference Liverpool, 26th April 2010 - Introducing 'take home' Naloxone in Wales" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ↑ Naloxone kits now available at drug stores as province battles fentanyl crisis - Injection drug can temporarily reverse overdoses Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "Every U.S. Public Library and YMCA Will Soon Get Narcan for Free". Time. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ↑ Reach for Me: Fighting to End the American Drug Overdose Epidemic Archived 2014-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Naloxone". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- Report on Naloxone and other opiate antidotes Archived 2003-12-15 at the Wayback Machine, by the International Programme on Chemical Safety

- What Is Naloxone? via Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration| SAMHSA Archived 2017-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Naloxone Overdose Prevention Laws | PDAPS.org Archived 2020-04-05 at the Wayback Machine

- "Naloxone Nasal Spray". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 2020-04-30. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- "FDA recommends health care professionals discuss naloxone with all patients when prescribing opioid pain relievers or medicines to treat opioid use disorder". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.</ref>