Olaparib

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lynparza, others |

| Other names | AZD-2281, MK-7339, KU0059436 |

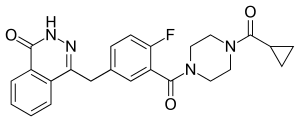

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | PARP inhibitor[1] |

| Main uses | Ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, peritoneal cancer[2][1] |

| Side effects | Tiredness, nausea, diarrhea, heartburn, cough, headache, shortness of breath, low white blood cells, low platelets[3] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| US NLM | Olaparib |

| MedlinePlus | a614060 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H23FN4O3 |

| Molar mass | 434.471 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Olaparib, sold under the brand name Lynparza, is a medication used to treat ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and peritoneal cancer.[2][1] It is used in cases that have failed other treatments and are likely BRCA mutation positive.[2] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include tiredness, nausea, diarrhea, heartburn, cough, headache, shortness of breath, low white blood cells, and low platelets.[3] Other side effects may include myelodysplastic syndrome and pneumonitis.[2] It should not be used when breastfeeding or pregnant.[3][2] It is a PARP inhibitor and works by blocking the ability of cancer cells to repair their DNA.[1]

Olaparib was approved for medical use in Europe and the United States in 2014.[2][3] In the United Kingdom a dose of 300 mg twice per day costs about £4,600 for 4 weeks as of 2021.[1] This amount in the United States costs about 14,000 USD.[8]

Medical uses

Dosage

The capsules and tablets are not interchangeable.[2]

The tablets are often taken at a dose of 300 mg twice per day.[1]

Side effects

Side effects include gastrointestinal effects such as nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite; fatigue; muscle and joint pain; and low blood counts such as anemia, with occasional leukemia.[2] Somnolence was sometimes seen in clinical trials which used doses higher than the approved schedule.[9]

Mechanism of action

Olaparib acts as an inhibitor of the enzyme poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), and is termed a PARP inhibitor. BRCA1/2 mutations may be genetically predisposed to development of some forms of cancer, and may be resistant to other forms of cancer treatment. However, these cancers sometimes have a unique vulnerability, as the cancer cells have increased reliance on PARP to repair their DNA and enable them to continue dividing. This means that drugs which selectively inhibit PARP may be of benefit if the cancers are susceptible to this treatment.[10][11]

History

In December 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved olaparib as monotherapy.[2][12][13][14][3] The FDA approval is in germline BRCA mutated (gBRCAm) advanced ovarian cancer[15] that has received three or more prior lines of chemotherapy.[2][16] The EMA public assessment report, which utilized the same phase II trial data, made reference to both "high grade serous ovarian cancers" and to the use of olaparib "not later than 8 weeks after a course of platinum-based medicines, when the tumour was diminishing in size or had completely disappeared".[14]

In breast cancer, olaparib is approved for gBRCAm HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer patients who have previously been treated with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant or metastatic setting. If patients have hormone receptor positive cancer, they should have received endocrine therapy where appropriate.[6] This approval was based on the OlympiAD randomised phase III trial, which showed a progression-free survival benefit for patients treated with olaparib compared to conventional chemotherapy [17][18]

In August 2017, olaparib tablets were approved in the United States for the maintenance treatment of adults with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer, who are in a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy.[19][20] The formulation was changed from capsules to tablets and the capsules were phased out in the United States.[19] The capsules and tablets are not interchangeable.[19]

The approval in the maintenance setting was based on two randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trials in patients with recurrent ovarian cancers who were in response to platinum-based therapy.[19] SOLO-2 (NCT01874353) randomized 295 patients with recurrent germline BRCA-mutated ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (2:1) to receive olaparib tablets 300 mg orally twice daily or placebo.[19] SOLO-2 demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS) in patients randomized to olaparib compared with those who received placebo, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.30 (95% CI: 0.22, 0.41; p<0.0001).[19] Study 19 (NCT00753545) randomized 265 patients regardless of BRCA status (1:1) to receive olaparib capsules 400 mg orally twice daily or placebo.[19] Study 19 demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in investigator-assessed PFS in patients treated with olaparib vs. placebo with a HR of 0.35.[19]

In January 2018, olaparib was approved in the United States for the treatment of patients with certain types of breast cancer that have spread (metastasized) and whose tumors have a specific inherited (germline) genetic mutation, making it the first drug in its class (PARP inhibitor) approved to treat breast cancer, and it is the first time any drug has been approved to treat certain patients with metastatic breast cancer who have a “BRCA” gene mutation.[21] Patients are selected for treatment with Lynparza based on an FDA-approved genetic test, called the BRACAnalysis CDx.[21]

In January 2018, olaparib became the first PARP inhibitor to be approved by the FDA for gBRCAm metastatic breast cancer. Olaparib was developed and first dosed into patients by the UK-based biotechnology company, KuDOS Pharmaceuticals, that was founded by Stephen Jackson of Cambridge University, UK.[22][23][24][25] Since KuDOS was acquired by AstraZeneca in 2006, the drug has undergone clinical development by AstraZeneca and Merck & Co.[26]

In December 2018, olaparib was approved in the United States for the maintenance treatment of adults with deleterious or suspected deleterious germline or somatic BRCA-mutated (gBRCAm or sBRCAm) advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer who are in complete or partial response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.[27] Adults with gBRCAm advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer should be selected for therapy based on an FDA-approved companion diagnostic.[27] Approval was based on SOLO-1 (NCT01844986), a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial that compared the efficacy of olaparib with placebo in patients with BRCA-mutated (BRCAm) advanced ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.[27] Patients were randomized (2:1) to receive olaparib tablets 300 mg orally twice daily (n=260) or placebo (n=131).[27]

In December 2019, olaparib was approved for the maintenance treatment of adults with deleterious or suspected deleterious germline BRCA-mutated (gBRCAm) metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, as detected by an FDA-approved test, whose disease has not progressed on at least 16 weeks of a first-line platinum-based chemotherapy regimen.[28] The FDA also approved the BRACAnalysis CDx test (Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Inc.) as a companion diagnostic for the selection of patients with pancreatic cancer for treatment with olaparib based upon the identification of deleterious or suspected deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.[28] Efficacy was investigated in POLO (NCT02184195), a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center trial that randomized (3:2) 154 patients with gBRCAm metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma to olaparib 300 mg orally twice daily or placebo until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.[28]

An April 2020 clinical trial indicated that olaparib treatment resulted in longer survival for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer compared to enzalutamide or abiraterone.[29]

Research

Olaparib in combination with temozolomide demonstrated substantial clinical activity in relapsed small cell lung cancer.[30]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 1051. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Lynparza- olaparib capsule". DailyMed. 27 September 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Lynparza EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ "Lynparza 50 mg hard capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ "Lynparza 100mg Film-Coated Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Lynparza- olaparib tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 1 June 2019. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ↑ "Lynparza EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ "Lynparza Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ↑ Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, et al. (July 2009). "Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (2): 123–34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. PMID 19553641.

- ↑ "Olaparib for the treatment of ovarian cancer" (PDF). europa.eu.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Menear KA, Adcock C, Boulter R, Cockcroft XL, Copsey L, Cranston A, et al. (October 2008). "4-[3-(4-cyclopropanecarbonylpiperazine-1-carbonyl)-4-fluorobenzyl]-2H-phthalazin-1-one: a novel bioavailable inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 51 (20): 6581–91. doi:10.1021/jm8001263. PMID 18800822.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Lynparza (olaparib) Capsules NDA #206162". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ "FDA approves Lynparza to treat advanced ovarian cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 19 December 2014. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 "Summary" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ Article, MesoWatch. "Ovarian Cancer Patients Can Now Access Tumor Blocking Drug Olaparib at Beginning of the Treatment". www.mesowatch.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ Wiggans AJ, Cass GK, Bryant A, Lawrie TA, Morrison J (May 2015). "Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD007929. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007929.pub3. PMC 6457589. PMID 25991068.

- ↑ Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu B, Domchek SM, Masuda N, et al. (August 2017). "Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (6): 523–533. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1706450. PMID 28578601.

- ↑ "FDA approves olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic breast cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 12 January 2018. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "FDA approves olaparib tablets for maintenance treatment in ovarian cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Lynparza tablets (olaparib)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- 1 2 "FDA approves first treatment for breast cancer with a certain inherited genetic mutation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 12 January 2018. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Coming ever closer – first PARP inhibitor licensed in Europe" (science blog). Cancer Research UK. 24 October 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "KuDOS Pharmaceuticals: First Patient Treated with New Anti-cancer Agent" (press release). Institute of Cancer Research. 25 July 2005. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "Olaparib: realising the promise of synthetic lethality". Cancer Research UK. 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "PARP inhibitors: Halting cancer by halting DNA repair". Cancer Research UK. 24 September 2020. Archived from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ↑ "National Cancer Institute - Olaparib after Initial Treatment Delays Ovarian Cancer Progression". Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "FDA approved olaparib (LYNPARZA, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP) for the maintenance treatment of adult patients with deleterious or suspected deleterious germline or somatic BRCA-mutated (gBRCAm or sBRCAm) advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer who are in complete or partial response to first-line platinum-based". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 December 2018. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 "FDA approves olaparib for gBRCAm metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 27 December 2019. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F, Shore N, Sandhu S, et al. (May 2020). "Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (22): 2091–2102. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911440. PMID 32343890.

- ↑ Farago AF, Yeap BY, Stanzione M, Hung YP, Heist RS, Marcoux JP, et al. (October 2019). "Combination Olaparib and Temozolomide in Relapsed Small-Cell Lung Cancer". Cancer Discovery. 9 (10): 1372–1387. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0582. PMC 7319046. PMID 31416802.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |