1980 Democratic Party presidential primaries

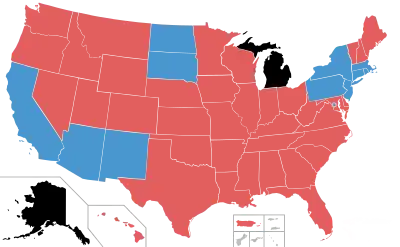

From January 21 to June 3, 1980, voters of the Democratic Party chose its nominee for president in the 1980 United States presidential election. Incumbent President Jimmy Carter was again selected as the nominee through a series of primary elections and caucuses, culminating in the 1980 Democratic National Convention, held from August 11 to August 14, 1980, in New York City.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3,346 delegates to the Democratic National Convention 1,674 delegates votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results of the 1980 Democratic National Convention | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carter faced a major primary challenger in Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts, who won 12 contests and received more than seven million votes nationwide, enough for him to refuse to concede the nomination until the second day of the convention. This remains the last primary election in which an incumbent president's party nomination was still contested going into the convention.

Primary race

At the time, Iran was experiencing a major uprising that severely damaged its oil infrastructure and greatly weakened its capability to produce oil.[1] In January 1979, shortly after Iran's leader Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled the country, lead Iranian opposition figure Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from a 14-year exile and with the help of the Iranian people toppled the Shah which in turn led to the installation of a new government that was hostile towards the United States.[1] The damage that resulted from Khomeini's rise to power would soon be felt throughout many American cities.[1] In the spring and summer of 1979 inflation was on the rise and various parts of the country were experiencing energy shortages.[2] The gas lines last seen just after the Arab/Israeli war of 1973 were back and President Carter was widely blamed.

President Carter's approval ratings were very low—28% according to Gallup,[3] with some other polls giving even lower numbers. In July Carter returned from Camp David and announced a reshuffling of his cabinet on national television, giving a speech whose downcast demeanor resulted in it being widely labelled the "malaise speech." While the speech caused a brief upswing in the president's approval rating, the decision to dismiss several cabinet members was widely seen as a rash act of desperation, causing his approval rating to plummet back into the twenties. Some Democrats felt it worth the risk to mount a challenge to Carter in the primaries. Although Hugh Carey and William Proxmire decided not to run, Senator Edward M. Kennedy finally made his long-expected run at the presidency.

Ted Kennedy had been asked to take his brother Robert's place at the 1968 Democratic National Convention and had refused. He ran for Senate Majority Whip in 1969, with many thinking that he was going to use this as a platform for the 1972 race.[4] However, then came the notorious Chappaquiddick incident that killed Kennedy's car passenger Mary Jo Kopechne and saw him somehow manage to evade punishment despite the fact that he had driven under the influence of alcohol and did not report the incident until the morning after it occurred.[5][6] Kennedy subsequently refused to run for president in 1972 and 1976. Many of his supporters suspected that Chappaquiddick had destroyed any ability he had to win on a national level. Despite this, in the summer of 1979, Kennedy consulted with his extended family, and that fall, he let it leak out that because of Carter's failings, 1980 might indeed be the year he would try for the nomination. Gallup had him beating the president by over two to one, but Carter remained confident, famously claiming at a June White House gathering of Congressmen that if Kennedy ran against him in the primary, he would "whip his ass."[7]

Kennedy's official announcement was scheduled for early November. A television interview with Roger Mudd of CBS a few days before the announcement went badly, however. Kennedy gave an "incoherent and repetitive"[8] answer to the question of why he was running, and the polls, which showed him leading the President by 58–25 in August now had him ahead 49–39.[9] Meanwhile, U.S. animosity towards the Khomeini régime greatly accelerated after 52 American hostages were taken by a group of Islamist students and militants at the U.S. embassy in Tehran and Carter's approval ratings jumped in the 60-percent range in some polls, due to a "rally ‘round the flag" effect[10] and an appreciation of Carter's calm handling of the crisis. Kennedy was suddenly left far behind. Carter beat Kennedy decisively in Iowa and New Hampshire. Carter decisively defeated Kennedy everywhere except Massachusetts, until impatience began to build with the President's strategy on Iran. When the primaries in New York and Connecticut came around, it was Kennedy who won.

Momentum built for Ted Kennedy after Carter's attempt to rescue the hostages on April 25 ended in disaster and drew further skepticism towards Carter's leadership ability.[11] Nevertheless, Carter was still able to maintain a substantial lead even after Kennedy won the key states of California and New Jersey in June. Despite this, Kennedy refused to drop out, and the 1980 Democratic National Convention was one of the nastiest on record. On the penultimate day, Kennedy conceded the nomination and called for a more liberal party platform in the Dream Shall Never Die speech, considered by many as the best speech of his career, and one of the best political speeches of the 20th Century.[12] On the stage on the final day, Kennedy for the most part ignored Carter.

As of 2023, Kennedy remains the last challenger to defeat an incumbent in any of his/her party's statewide presidential primary contests.

Far-right politician David Duke tried to run for the Democratic presidential nomination. Despite being six years too young to be qualified to run for president Duke attempted to place his name onto the ballot in twelve states stating that he wanted to be a power broker who could "select issues and form a platform representing the majority of this country" at the Democratic National Convention.[13][14]

Candidates

Nominee

| Candidate | Most recent office | Home state | Campaign | Popular

vote |

Contests won | Running mate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jimmy Carter |  |

President of the United States (1977–1981) |

.png.webp) Georgia |

(Campaign) |

10,043,016 (51.13%) |

36 IA, ME, NH, VT, AL, FL, GA, PR, IL, KS, WI, LA, TX, IN, NC, TN, NE, MD, OK, AR ID, KY, NV, MT, OH, WV, MO, OR, WA |

Walter Mondale | |

Withdrew during primaries or convention

| Candidate | Most recent office | Home state | Campaign

Withdrawal date |

Popular Vote | Contests Won | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ted Kennedy |  |

U.S. Senator from Massachusetts (1962–2009) |

Massachusetts |

(Campaign) |

7,381,693 (37.58%) |

12 AZ, MA, CT, NY, PA, ND, DC, CA, NJ, NM, RI, SD, VT, AK, MI | |

Other candidates

- Jerry Brown, Governor of California

- Cliff Finch, Governor of Mississippi

- Alice Tripp, activist from Minnesota

Results

| Date[15] (daily totals) |

Contest | Total pledged delegates |

Delegates won and popular vote | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jimmy Carter | Ted Kennedy | Jerry Brown | Others | Total vote | |||

| January 21 | Iowa[16][17] caucus | 45 | 30 (59.16%) |

15 (31.23%) |

– | (9.61%) |

|

| February 10 | Maine[18][19] caucus | 22 | 12 14,528[lower-alpha 1](43.59%) |

10 13,384[lower-alpha 2] (40.16%) |

4,621[lower-alpha 3] (13.87%) |

793[lower-alpha 4](2.38%) |

|

| February 26 | New Hampshire[20][21] primary | 19 | 10 52,692 (47.08%) |

9 41,745 (37.30%) |

10,743 (9.60%) |

6,750 (6.03%) |

|

| March 4 (125) |

Massachusetts[21] | 112 | 34 260,391 (28.70%) |

78 590,404 (65.07%) |

31,488 (3.47%) |

25,031 (2.76%) |

|

| Vermont | 13 | 10 29,015 (73.08%) |

3 10,135 (25.53%) |

(0.90%) |

553 (0.50%) |

||

| March 11 (325) |

Alabama | 47 | 47 194,680 (81.59%) |

31,624 (13.22%) |

(4.01%) |

12,418 (1.19%) |

|

| Delaware | 16 | 10 104 (60.47%) |

4 40 (23.26%) |

– | 3 28 (16.28%) |

||

| Florida | 98 | 72 665,683 (60.69%) |

27 256,564 (23.20%) |

53,422 (4.87%) |

123,400 (11.25%) |

||

| Georgia | 63 | 63 338,772 (88.04%) |

32,315 (8.40%) |

7,255 (1.89%) |

6,438 (1.67%) |

||

| Oklahoma | 42 | 42 4,440 (75.09%) |

575 (9.72%) |

19 (0.32%) |

879 (14.87%) |

||

| Washington | 59 | 33 2,898 (55.30%) |

15 1,295 (24.71%) |

25 (0.48%) |

12 1,023 (19.52%) |

||

| March 15 | Wyoming | 12 | 9 135 (64.59%) |

3 48 (22.97%) |

– | 26 (12.44%) |

|

| March 16 | Puerto Rico | 40 | 21 449,681 (51.57%) |

19 418,068 (48.04%) |

1,660 (0.19%) |

826 (0.10%) |

|

| March 18 | Illinois | 181 | 124 780,787 (65.01%) |

57 359,875 (29.96%) |

39,168 (3.26%) |

21,237 (1.77%) |

|

| March 23 | Virginia | 64 | 64 1,633 (84.26%) |

154 (7.95%) |

1 (0.05%) |

150 (7.74%) |

|

| March 25 (340) |

Connecticut | 54 | 25 87,207 (41.47%) |

29 98,662 (46.92%) |

5,386 (2.56%) |

19,020 (9.04%) |

|

| New York | 286 | 117 406,305 (41.08%) |

169 582,757 (58.92%) |

– | – | ||

| April 1 (115) |

Kansas | 38 | 24 109,807 (56.63%) |

14 61,318 (31.62%) |

9,434 (4.87%) |

13,359 (1.13%) |

|

| Wisconsin | 77 | 50 353,662 (56.17%) |

27 189,520 (30.10%) |

74,496 (11.83%) |

11,941 (1.90%) |

||

| April 5 | Louisiana | 51 | 36 199,956 (55.74%) |

15 80,797 (22.52%) |

16,774 (4.68%) |

61,214 (17.07%) |

|

| April 12 (66) |

Arizona | 28 | 12 7,592 (43.81%) |

16 9,738 (56.19%) |

– | – | |

| South Carolina | 38 | 25 7,305 (64.25%) |

579 (5.09%) |

– | 13 3,486 (30.66%) |

||

| April 22 (266) |

Pennsylvania | 189 | 94 732,332 (45.40%) |

95 736,954 (45.68%) |

37,669 (2.34%) |

93,865 (6.60%) |

|

| Missouri | 77 | 77 415 (76.15%) |

55 (10.09%) |

– | 75 (13.76%) |

||

| Vermont caucuses[22] | (32%) | (45%) | (23%) | ||||

| April 26 | Michigan caucuses[23] | (46.68%) | (48.08%) | – | (5.24%) | ||

| May 3 | Texas | 152 | 87 770,390 (55.93%) |

36 314,129 (22.81%) |

35,585 (2.58%) |

29 257,252 (18.68%) |

|

| May 6 | Colorado | 39 | 16 417 (41.70%) |

12 295 (29.5%) |

– | 11 288 (28.8%) |

|

| District of Columbia | 14 | 5 23,697 (36.94%) |

9 39,561 (61.67%) |

– | 892 (1.39%) |

||

| Indiana | 81 | 55 400,849 (67.68%) |

26 193,290 (32.32%) |

– | – | ||

| North Carolina | 70 | 56 516,778 (70.09%) |

14 130,684 (17.73%) |

21,420 (2.91%) |

68,380 (9.28%) |

||

| Tennessee | 57 | 46 221,658 (75.22%) |

11 53,258 (18.07%) |

5,612 (1.90%) |

14,152 (4.79%) |

||

| May 13 (85) |

Maryland | 60 | 33 226,528 (47.48%) |

27 181,091 (37.96%) |

14,313 (3.00%) |

55,158 (11.58%) |

|

| Nebraska | 25 | 14 72,100 (46.87%) |

11 57,826 (37.58%) |

5,478 (3.56%) |

18,449 (11.99%) |

||

| May 20 (181) |

Michigan caucuses | 142 | – | – | 42 23,043 (29.38%) |

100 55,381 (70.62%) |

|

| Oregon | 39 | 25 208,693 (56.83%) |

14 114,651 (31.22%) |

(9.37%) |

44,978 (2.57%) |

||

| May 27 | Arkansas | 33 | 21 269,375 (60.09%) |

6 78,542 (17.52%) |

– | 100,373 (22.39%) |

|

| Idaho | 17 | 13 31,383 (62.17%) |

4 11,087 (21.96%) |

2,078 (4.12%) |

5,934 (11.76%) |

||

| Kentucky | 50 | 37 160,819 (66.92%) |

13 55,167 (22.96%) |

– | 24,345 (10.14%) |

||

| Nevada | 13 | 5 25,159 (37.58%) |

4 19,296 (28.82%) |

– | 4 22,493 (33.60%) |

||

| June 3 (699) |

California | 303 | 138 1,266,216 (37.64%) |

165 1,507,142 (44.80%) |

135,962 (4.04%) | 454,538 (13.51%) |

|

| Montana | 19 | 11 67,033 (51.46%) |

8 47,991 (36.65%) |

– | 15,579 (11.89%) |

||

| New Jersey | 114 | 46 212,387 (37.87%) |

68 315,109 (56.18%) |

– | 33,412 (5.96%) |

||

| New Mexico | 20 | 9 66,621 (41.80%) |

11 73,721 (46.26%) |

– | 19,023 (11.94%) |

||

| Ohio | 164 | 88 605,744 (51.06%) |

76 523,874 (44.16%) |

– | 56,792 (4.78%) |

||

| Rhode Island | 23 | 6 9,907 (25.85%) |

17 26,177 (68.30%) |

310 (0.81%) | 1,931 (5.05%) |

||

| South Dakota | 19 | 9 31,251 (45.45%) |

10 33,418 (48.60%) |

– | 4,094 (5.95%) |

||

| West Virginia | 37 | 23 197,687 (62.18%) |

14 120,247 (37.82%) |

– | – | ||

| Total[24] | 10,043,016 (51.13%) | 7,381,693 (37.58%) | 575,296 (2.93%) | 1,647,909 (8.36%) | |||

Endorsements

- U.S. Senators

- Senator John Glenn of Ohio[25]

- Senator Joe Biden of Delaware

- Federal Officials

- Governors

- Governor Edward J. King of Massachusetts[26]

- State Officials

- Treasurer Gertrude Donahey of Ohio[25]

- Secretary of State Anthony J. Celebrezze, Jr., of Ohio[25]

- State Senate president Oliver Ocasek of Ohio[25]

- State Representative Mary O. Boyle of Ohio[25]

- Municipal Officials

- Mayor William Donald Schaefer of Baltimore[27]

- U.S. Senators

- Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, Senate Majority Leader

- Senator Howard Metzenbaum of Ohio[25]

- Senator Henry M. "Scoop" Jackson of Washington

- Ambassador at Large and United States Coordinator for Refugee Affairs and Former Senator Dick Clark of Iowa [28]

- House of Representatives

- Representative Paul Simon of Illinois[29]

- Representative Chris Dodd of Connecticut[30]

- Representative Toby Moffett of Connecticut[30]

- Representative William R. Ratchford of Connecticut[30]

- Representative William R. Cotter of Connecticut[30]

- Representative Eugene Atkinson of Pennsylvania[31]

- Representative Barbara Mikulski of Maryland[27]

- Representative Louis Stokes of Ohio[25]

- Representative Mo Udall of Arizona

- Governors

- Former Governor Rafael Hernandez Colon of Puerto Rico[32]

- Former Governor Patrick Lucey of Wisconsin[33]

- Former Governor Michael DiSalle of Ohio[25]

- State Officials

- State Representative Frank Giglio of Illinois[29]

- Municipal Officials

- Mayor Jane Byrne of Chicago[29]

- City Treasurer Cecil A. Partee of Chicago[29]

- Alderman Edward Vrdolyak of Chicago's 10th Ward[29]

- Alderman Wilson Frost of Chicago's 34th Ward[29]

- Alderman Eugene Sawyer of Chicago's 6th Ward[29]

- Mayor William J. Green III of Philadelphia[31]

- Former Mayor Jerry Springer of Cincinnati[25]

- Party Officials

- Cuyahoga County Democratic Party chairman Tim Hagan[25]

- Labor Unions

- Individuals

- Author Norman Mailer of New York[34]

- Actor Warren Beatty[35]

- J. B. Pritzker, high school student and member of the Pritzker family[36]

- Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union Local 617 president Phil Hare[29]

Convention

Presidential tally[37]

- Jimmy Carter (inc.) – 2,123 (64.04%)

- Ted Kennedy – 1,151 (34.72%)

- William Proxmire – 10 (0.30%)

- Koryne Kaneski Horbal – 5 (0.15%)

- Scott M. Matheson – 5 (0.15%)

- Ron Dellums – 3 (0.09%)

- Robert Byrd – 2 (0.06%)

- John Culver – 2 (0.06%)

- Kent Hance – 2 (0.06%)

- Jennings Randolph – 2 (0.06%)

- Warren Spannaus – 2 (0.06%)

- Alice Tripp – 2 (0.06%)

- Jerry Brown – 1 (0.03%)

- Dale Bumpers – 1 (0.03%)

- Hugh L. Carey – 1 (0.03%)

- Walter Mondale – 1 (0.03%)

- Edmund Muskie – 1 (0.03%)

- Thomas J. Steed – 1 (0.03%)

In the vice-presidential roll call, Mondale was re-nominated with 2,428.7 votes to 723.3 not voting and 179 scattering.

See also

Notes

- 1,017 SDE

- 847 SDE

- 263 SDE

- 52 SDE

References

- "Oil Squeeze". Time magazine. 1979-02-05. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Inflation-proofing". ConsumerReports.org. 2010-02-11. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- "Poll: Bush approval mark at all-time low". CNN. Archived from the original on 2009-04-25. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- U.S. News & World Report January 1969.

- "How Ted Kennedy's '80 Challenge To President Carter 'Broke The Democratic Party'". NPR. January 17, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- Sanburn, Josh (July 17, 2019). ""The Kennedy Machine Buried What Really Happened": Revisiting Chappaquiddick, 50 Years Later". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- "Press: Whip His What?". Time. 25 June 1979. Archived from the original on 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- Allis, Sam (2009-02-18). "Chapter 4: Sailing Into the Wind: Losing a quest for the top, finding a new freedom". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2009-02-22. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- Time Magazine, 11/12/79

- Marra, Robin F.; Ostrom, Charles W.; Simon, Dennis M. (1 January 1990). "Foreign Policy and Presidential Popularity: Creating Windows of Opportunity in the Perpetual Election". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 34 (4): 588–623. doi:10.1177/0022002790034004002. JSTOR 174181. S2CID 154620443.

- "The Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-21. Retrieved 2013-12-18.

- Kuypers, Jim A., ed. (2004). The Art of Rhetorical Criticism. Pearson/Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-37141-9, p. 185.

- "Duke to run". The Times. May 21, 1979. p. 10. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ku Klux Klansman egged on Alexandria street". The Times. June 23, 1979. p. 4. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1980 Presidential Primary Calendar". Archived from the original on 2020-03-29. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- "Kennedy has failed to exploit changes in delegate selection". The Courier-Journal. February 3, 1980. p. 51. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Clymer, Adam (January 23, 1980). "Candidates shifting tactics". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

Winebrenner, Hugh; Goldford, Dennis J. (2010). "The 1980 caucuses: a media event becomes an institution". The Iowa precinct caucuses: the making of a media event (3rd ed.). Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-58729-915-5. Archived from the original on 2014-06-18. Retrieved 2016-10-14. - "Maine officials say Carter victory was slim". The Courier-News. February 16, 1980. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lindsay, Christopher (Associated Press) (February 15, 1980). "Carter margin over Kennedy smaller than first believed". LexisNexis Academic.

Carter received 14,528 caucus votes, 43.6 percent; Kennedy received 13,384 votes, 40.2 percent; Brown received 4,621 votes, 13.9 percent; Uncommitted were 793 votes, 2.4 percent.

- "New Hampshire winners look to future contests". The Courier. February 27, 1980. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Elections Research Center (1981). Scammon, Richard M.; McGillivray, Alice V. (eds.). America votes 14: a handbook of contemporary American election statistics. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly. pp. 33–39. ISSN 0065-678X. OCLC 1240412.

- "Kennedy and Bush still losing in delegates". National Journal. 12 (17): 69. April 26, 1980. ISSN 0360-4217.

Vermont—Kennedy did surprisingly well in Democratic town and city caucuses on April 22 to choose delegates to the May 24 state convention, where the state's 12 national convention seats will be filled on the basis of the caucus vote. Kennedy won roughly 45 per cent of the vote to Carter's 32 per cent; the rest were uncommitted.

- Johnson, Malcolm (Associated Press) (April 28, 1980). "Kennedy wins again but gains little". LexisNexis Academic.

The final totals showed Kennedy with 7,793 votes and Carter with 7,567. About 850 votes were divided between uncommitted and other candidates, but neither category had enough votes to win a delegate.

- "US President – D Primaries Race – Feb 26, 1980". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- "1980 Ohio Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1980 Massachusetts Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1980 Maryland Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/31/archives/carter-loses-clark-to-kennedys-camp-move-by-the-exsenator-is-seen.html)

- "1980 Illinois Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1980 Connecticut Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1980 Pennsylvania Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1980 Puerto Rico Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1980 Wisconsin Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "1980 New York Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "1980 California Democratic Primary". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Meyer, Theoderic (October 5, 2018). "The Worst Job in American Politics". Politico. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- "US President – D Convention Race – Aug 11, 1980". Our Campaigns. Archived from the original on 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

Further reading

- Norrander, Barbara (1986). "Correlates of Vote Choice in the 1980 Presidential Primaries". Journal of Politics. 48 (1): 156–166. doi:10.2307/2130931. JSTOR 2130931. S2CID 143610156.

- Southwell, Priscilla L. (1986). "The Politics of Disgruntlement: Nonvoting and Defection among Supporters of Nomination Losers, 1968–1984". Political Behavior. 8 (1): 81–95. doi:10.1007/BF00987593. S2CID 154450840.

- Stanley, Timothy (2010). Kennedy vs. Carter: The 1980 Battle for the Democratic Party's Soul. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1702-9.

- Stone, Walter J. (1984). "Prenomination Candidate Choice and General Election Behavior: Iowa Presidential Activists in 1980". American Journal of Political Science. 28 (2): 361–378. doi:10.2307/2110877. JSTOR 2110877.

- Ward, Jon (2019). Camelot's End : Kennedy vs. Carter and the Fight that Broke the Democratic Party. New York: Twelve. ISBN 978-1-4555-9138-1.