1994 Turkish local elections

Local elections were held in Turkey on 27 March 1994.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 3,215 district municipalities and 16 metropolitan municipalities of Turkey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

Background

1989 local elections

In the 1989 Turkish local elections, ANAP suffered a nationwide rout in what many saw as a referendum on the Turgut Özal administration.[1] Nurettin Sözen, a doctor from the center-left Social Democratic People’s Party (SHP) became Istanbul’s mayor, creating hopes for the left’s nationwide rise. The SHP promised a break from the past with its platform focused on clean government and anti-corruption. But under the new administration, things only appeared to get worse. For one thing, Istanbul's population nearly doubled in the 1990s, creating massive demand for public services.[1]

Istanbul in the 1990s

Istanbul had a large garbage problem in the 1990s and it reached a new high with the Üsküdar garbage explosion when a trash heap in a slum neighborhood exploded. Methane gas had built up beneath the filth, finally igniting and causing an avalanche that killed 27 of the hapless poor.[2] Also, that winter the air was filled with soot from the millions of coal-burning ovens that families were using to heat their homes. Many began wearing surgical masks before going outside.[3]

The İSKİ Scandal

Three years into Sözen’s term, the İSKİ Scandal broke out. Ergün Göknel, a Sözen appointee who ran the Istanbul Water and Sewerage Administration (İSKİ) had divorced his wife in 1992 to marry an İSKİ employee three decades his junior, offering his wife a divorce settlement valued in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.[4] But his former wife was not content to console herself quietly with her new fortune. She went to the press to declare the size of the settlement, which was far too large for a public servant to afford, and to voice her suspicions about her husband’s alleged illicit dealings. This triggered a flurry of speculation in the press about corruption in İSKİ and the SHP, and Turkey’s prosecutors sprang into action, preparing a handful of high-profile cases against leftist leaders.[5] While İSKİ burned, Göknel married his new wife at the Istanbul Hilton, the city’s first American-built deluxe hotel. Mayor Sözen, infuriated, removed Göknel from his post and declared that he would support the harshest disciplinary action against any corrupt dealings uncovered in a criminal investigation.[4] It was a buck too short, a day too late: the Turkish left, already weakened due to anti-leftist measures implemented in the aftermath of the 1980 coup, died in Istanbul in 1994.[1]

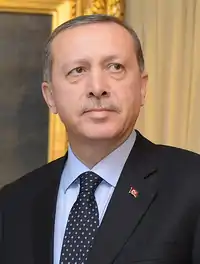

Rise of Erdoğan

The İSKİ Scandal was unfolding during the peak of the local-elections season, and with every detail it seemed to prove what Necmettin Erbakan and his Welfare Party had been saying all along: that the people were suffering because they were governed by elites whose moral fiber had been rotted by Western ways. Turkey’s leaders were too busy fleecing the public and having affairs with each other to bother themselves with the problems of the suffering masses.

Erdogan’s 1994 campaign played upon these themes with tremendous virtuosity. He called the RP the “voice of the silent masses.”[6] While other parties lacked the grassroots infrastructure to communicate directly with the residents of Istanbul’s shanty towns, the RP machine could interact with them at a highly granular level, thanks to its vast database.[7] Populism, too, helped the RP’s cause. The party pledged to keep bread prices low through municipally subsidized bread factories, and RP representatives handed out coal and groceries in poor neighborhoods, once again taking advantage of their computerized database. It was said that one RP lieutenant even handed out gold coins to prospective voters.[8]

Results

The 1994 nationwide local elections showed that the vast majority of the voting public was still not comfortable with the Islamist RP alternative, even when the establishment parties were at their worst.[1]

Provincial assemblies

| Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True Path Party | 6,027,095 | 21.41 | |

| Motherland Party | 5,937,031 | 21.09 | |

| Welfare Party | 5,388,195 | 19.14 | |

| Social Democratic Populist Party | 3,807,921 | 13.53 | |

| Democratic Left Party | 2,463,853 | 8.75 | |

| Nationalist Movement Party | 2,239,117 | 7.95 | |

| Republican People's Party | 1,297,371 | 4.61 | |

| Great Unity Party | 355,271 | 1.26 | |

| Democratic Party | 148,719 | 0.53 | |

| Nation Party | 126,118 | 0.45 | |

| Rebirth Party | 104,285 | 0.37 | |

| Socialist Unity Party | 80,714 | 0.29 | |

| Workers' Party | 79,588 | 0.28 | |

| Independent | 96,913 | 0.34 | |

| Total | 28,152,191 | 100.00 | |

Metropolitan municipality mayors

| Metropolitan municipality | Mayor | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Adana | Aytaç Durak | Motherland Party (ANAP) |

| Ankara | Melih Gökçek | Welfare Party (RP) |

| Antalya | Hasan Subaşı | True Path Party (DYP) |

| Bursa | Erdem Saker | Motherland Party (ANAP) |

| Diyarbakır | Ahmet Bilgin | Welfare Party (RP) |

| Erzurum | Ersan Gemalmaz | Welfare Party (RP) |

| Eskişehir | Aydın Arat | True Path Party (DYP) |

| Gaziantep | Celal Doğan | Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP) |

| İstanbul | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | Welfare Party (RP) |

| İzmir | Burhan Özfatura | True Path Party (DYP) |

| Kayseri | Şükrü Karatepe | Welfare Party (RP) |

| Kocaeli | Sefa Sirmen | Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP) |

| Konya | Halil Ürün | Welfare Party (RP) |

| Mersin | Okan Merzeci | Motherland Party (ANAP) |

| Samsun | Muzaffer Önder | Republican People's Party (CHP) |

Mayor of other municipalities

|

|

|

|

References

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2017). The new sultan : Erdogan and the crisis of modern Turkey. London. ISBN 978-1-78453-826-2. OCLC 974880239.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Newman, Barry (12 September 1994). "Turning eastward: Islamic party's gains in Istanbul stir fears of a radical Turkey". The Wall Street Journal.

- White, Jenny B. (1995). "Islam and democracy: the Turkish experience". Current History. 94 (588). doi:10.1525/curh.1995.94.588.7. S2CID 251858361.

- Öktener, Aslı (8 February 2001). "Nurdan Erbuğ'un pişmanlığı!". Milliyet.

- Montalbano, William (4 November 1994). "The army's prestige is growing amid political scandal". The Guardian.

- "Kasımpaşa'dan Çankaya'ya, yoksulluktan yolsuzluk suçlamalarına Erdoğan'ın hayatı". T24. 10 August 2014.

- Eligür, Banu (2010). The Mobilization of Political Islam in Turkey. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Akıncı, Uğur (1999). "The Welfare Party's municipal track record: evaluating Islamist municipal activism in Turkey". Middle East Journal. 53 (1): 77.

External links

- Results of the local elections (in Turkish) Archived 2009-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

.jpg.webp)