1999 İzmit earthquake

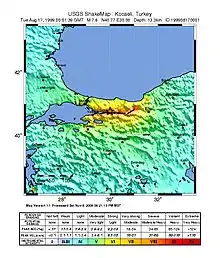

On 17 August 1999, a catastrophic magnitude 7.6 earthquake struck the Kocaeli Province of Turkey, causing monumental damage and between 17,127 and 18,373 deaths.[8] Named for the quake's proximity to the northwestern city of İzmit, the earthquake is also commonly referred to as the 17 August Earthquake or the 1999 Gölcük Earthquake.[9] The earthquake occurred at 03:01 local time (00:01 UTC) at a shallow depth of 15 km. A maximum Mercalli intensity of X (Extreme) was observed. The earthquake lasted for 37 seconds, causing seismic damage and is widely remembered as one of the deadliest natural disasters in modern Turkish history.

Collapsed buildings in İzmit | |

| |

| UTC time | 1999-08-17 00:01:38 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 1655218 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 17 August 1999 |

| Local time | 03:01 |

| Duration | 37 seconds[1] |

| Magnitude | 7.6 Mw[2][3] 7.8 Ms[4] |

| Depth | 15.0 km (9.3 mi)[2] |

| Epicenter | 40.748°N 29.864°E |

| Fault | North Anatolian Fault |

| Type | Strike-slip[1] |

| Areas affected | Turkey |

| Total damage | 3–8.5 billion USD[3] |

| Max. intensity | X (Extreme)[5] |

| Peak acceleration | 0.45 g[6] |

| Tsunami | 2.52 m (8.3 ft)[3] |

| Casualties | 17,127–18,373 dead[7] 43,953–48,901 injured[7][8] 5,840 missing[8] |

The 1999 earthquake was part of a seismic sequence along the North Anatolian Fault that started in 1939, causing large earthquakes that moved progressively from east to west over a period of 60 years.[10] The earthquake encouraged the establishment of a so-called earthquake tax aimed at providing assistance to the ones affected by the earthquake.[11]

Tectonic setting

The North Anatolian Fault Zone, where the earthquake occurred, is a 1,200 km (750 mi) right-lateral strike-slip fault zone. It extends from the Gulf of Saros to Karlıova. It formed around 13—11 million years ago in the eastern part of Anatolia and developed westwards. The fault eventually developed at the Marmara Sea around 200,000 years ago despite the shear-related movement in a rather broad zone which had already started in late Miocene.[12]

The fault zone has a diverse geomorphological structure and is seismically active. It produced a series of earthquakes as large as 8.0 on the moment magnitude scale. Since the 17th century, it has shown cyclical behavior, with century-long large earthquake cycles beginning in the east and continuing westward. Although the record is less clear for earlier times, active seismicity could still inferred in that timespan. The 20th century earthquake record has been interpreted as where every earthquake concentrates the stress at the western tips of the ruptured areas leading to westward migration of larger earthquakes. The İzmit and November 12, 1999 events increased stress on the Marmara segment of the fault. An earthquake of up to magnitude 7.6 event was expected between 2005 and 2055 with a probability of 50 percent on this segment.[12] Presently, the deformation of rocks by stress in the Marmara Sea region is asymmetric. This is conditioned by the regional geology and is believed to be such the case for most of the NAFZ.[12]

Earthquake

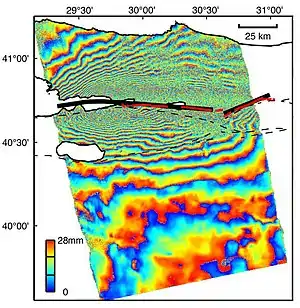

The 17 August 1999 earthquake was the 7th in a sequence of westward-migrating seismic sequence along the NAFZ. This earthquake sequence began in 1939 and ruptured along a 1000-km part of the fault zone, with horizontal displacements of up to 7.5 m.[6]

The maximum observed ground motion was 0.45 g. The earthquake lasted 35–45 seconds according to various sources. The closest cities affected were İzmit, Gölcük, Yalova, and Adapazarı; all located near the eastern end of the Marmara Sea, within the Gulf of İzmit. The earthquake also caused serious damage in Istanbul, especially in the district of Avcılar which is located in the western part of the city, around 70 km away from the epicenter. Despite the distance, it killed about 1,000 people in the district. The earthquake caused a surface rupture comprising four segments; the Hersek/Karamürsel–Gölcük, İzmit–Lake Sapanca, Lake Sapanca–Akyazı, Akyazı–Gölyaka and Gölyaka–Düzce segments. These segments altogether measured over 125 km. All the segments are separated by pull-apart stepovers of 1 to 4 km in width. The maximum offset throughout the rupture was measured on the Sapanca–Akyazı segment where the surface break displaced a road and a tree line by 5.2 m. It also showed pure strike-slip, and the fault plane is almost vertical in most of the places where a surface break was observed. Most of the major aftershocks (M>4) were located near Düzce, south of Adapazarı, in Sapanca, in İzmit, and the Çınarcık area. At Değirmendere, a small coastal town west of Gölcük, the rupture cut the edge of a fan delta where the center of the town was located, which caused a slump measuring 300 m long and 100 m wide, as a result a part of the town center slid under the water, including a hotel and several shops and restaurants. At another fan delta east of Gölcük, which is within the step-over area of the ruptures, the fault produced a 2 m-high normal fault scarp.[6]

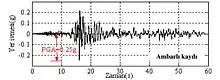

Data was used from seven broadband stations as well as some other short-period stations across the area to calculate the regional moment tensor of the mainshocks and larger aftershocks and as a result most of the earthquakes were found to be split in segments with the moment tensor's focal mechanism reading either a strike-slip on the fault which is west-east striking or normal faulting which is between rupture segments which also proves that the main characteristic of the quake is dextral strike-slip.[13]

From the timing of P-wave and S-wave arrivals at seismometers, there is strong evidence that the rupture propagated eastwards from the epicenter at speeds in excess of the S-wave velocity, making this a supershear earthquake.[14]

Impact

Earthquake damage

| Province | Deaths | Injuries |

|---|---|---|

| Bolu | 264 | 1,163 |

| Bursa | 263 | 333 |

| Eskişehir | 86 | 83 |

| Istanbul | 978 | 3,547 |

| Kocaeli | 8,644 | 9,211 |

| Sakarya | 2,627 | 5,084 |

| Tekirdağ | 0 | 35 |

| Yalova | 2,501 | 4,472 |

| Zonguldak | 3 | 26 |

Ten of Turkey's 81 provinces were affected with deaths and collapsed buildings.[15] An official Turkish estimate dated 19 October 1999 placed the toll at 17,127 killed and 43,953 injured, but many sources suggest the actual figure may have been closer to 45,000 dead and a similar number injured.[7][8] Reports from September 1999 stated 127,251 buildings were damaged to varying extents and at least 60,434 others collapsed.[15] More than 250,000 people became homeless.[16] About 60 km of the Istanbul-Ankara highway, almost 500 km electricity cables and over 3,000 electricity distribution towers were damaged.[17]

Over 800 people were killed in İzmit.[18] In Gölcük, at least 4,556 people died, 5,064 were injured, thousands were left missing and at least 500 buildings collapsed, trapping about 20,000 families.[15][19] About 200 sailors went missing after a naval base collapsed.[18] There was also destruction in Yalova; 2,501 people died, 4,472 were injured and 10,134 buildings collapsed.[15] The cause of most damage in Yalova was suspected to be liquefaction-induced. Since the area mostly comprised Quaternary alluvial soil, it was prone to liquefaction. The approximately 200 drilling sites and boreholes, and many streams or rivers, factored in the severe liquefaction.[20]

In Istanbul, at least 978 people were killed and 3,547 others sustained injuries.[19] Severe damage in the city was concentrated in Avcılar district. Avcılar was built on relatively weak ground, mainly composed of poorly consolidated Cenozoic sedimentary rocks, which made the district vulnerable to earthquakes.[21] In Eskişehir, there were 86 deaths and 70 buildings collapsed.[15] At least 263 people died and 333 others were injured in Bursa.[15] Three deaths and 26 injuries were reported in Zonguldak.[15] At least 2,627 people were also killed and 5,084 others were hurt in Sakarya Province.[15]

Private contractors faced backlash for using cheap materials in their construction of residential buildings. Many of these contractors were prosecuted but few were found guilty. Government officials also faced backlash for not properly enforcing earthquake resistant building codes.[22] Direct cost of damage is estimated at US $6.5 billion, but secondary costs could exceed US $20 billion.[23] In 2010, the research branch of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey stated the number of casualties as 18,373. In the same report, it stated there were 48,901 injured, 505 permanently injured, 96,796 homes heavily damaged or destroyed, 15,939 businesses heavily damaged or destroyed, 107,315 homes moderately damaged, 16,316 businesses moderately damaged, 113,382 homes slightly damaged, 14,657 businesses slightly damaged, 40,786 prefabricated homes distributed and 147,120 people rehoused into these homes.[24]

There was extensive damage to several bridges and other structures on the Trans-European Motorway, including 20 viaducts, 5 tunnels, and several overpasses. Damage ranged from spalling concrete to total deck collapse.[25]

Oil refinery fire

The earthquake triggered a fire at the Tüpraş petroleum refinery. The fire began at a state-owned tank farm and was initiated by naphtha that had spilled from a holding tank. Breakage in water pipelines and earthquake damage made firefighting attempts ineffective. Aircraft were called in to douse the flames with foam. The fire spread for several days. An evacuation was warranted for an area within 5 km of the refinery. The fire was declared under control five days later after claiming at least 17 tanks and an unknown quantity of complex piping.[26] People within 2-3 mi of the refinery had to evacuate dspite some areas still in the process of search and rescue.[27]

Tsunami

At least 155 deaths were associated with the tsunami.[28] Many field studies were made about the tsunami in the Gulf of İzmit. Along the northern coast of the gulf, in the basin between Hereke and Tüpraş Petroleum Refinery, the tsunami was leading depression wave. The run-up wave heights in this area ranged from 1.5–2.6 m (4 ft 11 in – 8 ft 6 in). The first series of waves arrived at the north coast a few minutes after the earthquake, and had a period of around a minute. The hardest hit areas were Şirinyalı, Kirazlıyalı, Yarımca, Körfez, and the refinery. The tsunami carried mussels into buildings, damaged doors and windows. At Körfez, inundation was up to 35 m (115 ft). There were clear watermarks on the walls of buildings including the police station in Hereke, and at a restaurant near Körfez. Locals reported the first waves arrived at Kirazlıyalı from a southeastern direction and at Körfez from a southern direction. Along the southern coast of the gulf between Değirmendere and Güzelyalı, run-up measured 0.8–2.5 m (2 ft 7 in – 8 ft 2 in). The tsunami was recorded as a leading depression wave to the west of Kavaklı up to Güzelyalı. There, the wave was noticed by locals immediately after the earthquake. There was severe coastal subsidence and slumping of a park near Değirmendere. The subsided area was 250 m (820 ft) along the shore and 70 m (230 ft) perpendicular to shore. The same area included two piers, a hotel, a restaurant, a cafe and several trees. Locals at the coast near Değirmendere observed the sea receding by about 150 m (490 ft) in less than two minutes. When the sea came back, it inundated up to 35 m (115 ft) inland, as shown by the mussels and dead fish left in the flooded areas.[29] The tsunami also caused damage to the naval base nearby.[30]

Aftershocks

A Mw 5.2 aftershock hit near İzmit on August 31, causing one additional fatality and 166 injuries, with tremors being felt in Istanbul.[31] Another Mw 5.9 aftershock hit on September 13, causing seven deaths and 422 injuries.[32] Another aftershock measuring Mw 5.2 occurred on September 29, killing one person in Istanbul.[33] A Mw 5.0 aftershock on November 7 killed one person in Sakarya Province,[34] while another Mw 5.7 event on November 11 in the same province caused two deaths and 171 injuries.[35] On 23 August 2000, a Mw 5.3 earthquake caused 22 injuries in Sakarya.[36] Another Mw 5.0 event hit on 26 August 2001, causing two injuries in Bolu.[37]

| Province | Destroyed | Moderately damaged | Slightly damaged |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bolu | 3,226 | 4,782 | 3,233 |

| Bursa | 32 | 109 | 431 |

| Eskişehir | 70 | 32 | 204 |

| Istanbul | 3,614 | 12,370 | 10,630 |

| Kocaeli | 23,254 | 21,316 | 21,481 |

| Sakarya | 20,104 | 11,381 | 17,953 |

| Yalova | 10,134 | 8,870 | 14,470 |

| Total: | 60,434 | 58,860 | 68,391 |

Response

A massive international response was mounted to assist in digging for survivors and to assist the wounded and homeless. Rescue teams were dispatched within 24–48 hours of the disaster, and the assistance to the survivors was channeled through NGOs, Turkish Red Crescent and local search and rescue organizations.

The following table shows the breakdown of rescue teams by country in the affected locations:

| Location | Foreign search and rescue teams |

|---|---|

| Gölcük, Kocaeli | Hungary, Israel, France, South Korea, Belgium, Russia |

| Yalova | Germany, Hungary, Israel, Poland,[38] United Kingdom, France, Japan, Austria, Romania, South Korea |

| Avcılar, Istanbul | Greece, Germany |

| İzmit, Kocaeli | Russia, Hungary, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, United States, Iceland, South Korea |

| Sakarya | Bulgaria, Egypt, Germany, Spain |

| Düzce | Poland,[38] United Kingdom |

| Bayrampaşa, Istanbul | Italy |

| Kartal, Istanbul | Azerbaijan |

Search and Rescue Effort as of 19 August 1999. Source: USAID[39]

In total, rescue teams from 12 countries assisted in the rescue effort. Greece was the first nation to pledge aid and support. Within hours of the earthquake, the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs contacted their counterparts in Turkey, and the minister sent his personal envoys to Turkey. The Ministry of Public Orders sent in a rescue team of 24 people and two trained rescue dogs, as well as fire-extinguishing planes to help with putting out the fire in the Tüpraş Oil refinery.[40]

Oil Spill Response Limited was activated by BP to deploy from the United Kingdom to the Tüpraş Refinery where their responders successfully contained the previously uncontrolled discharge of oil from the site into the sea.[41]

The UK announced an immediate grant of £50,000 to help the Turkish Red Crescent, while the International Red Cross and Red Crescent pledged £4.5 million to help victims. Blankets, medical supplies and food were flown from Stansted airport. Engineers from Thames Water went to help restore water supplies.[42]

US President Bill Clinton later visited Istanbul and İzmit to examine the level of destruction and meet with the survivors.[43]

Future risk

There has been an increased seismic activity in the Eastern Sea of Marmara since 2002 and a quiescence of earthquakes on the Princes' Islands Segment of the North Anatolian Fault off the southern coast of Istanbul. This suggests that the 150-km long submarine seismic gap below the Sea of Marmara could point out to a future, large earthquake. These possibilities are quite important, with respect to the segmentation of major fault ruptures along the North Anatolian Fault Zone in north-western Turkey. With the possible activation of segments towards the metropolitan areas of Istanbul, the Princes' Islands gap should be considered to have an impact on the large seismic hazard potential for Istanbul.[44]

Despite a long-term earthquake catalogue existing for the North Anatolian Fault Zone and for the Istanbul area in particular, the basic understanding of the seismicity there is still a long way off. The observation of a seismic gap in vicinity to the Istanbul metropolitan area was made possible through deploying a dense network of seismic stations and small arrays near the fault trace south of the Princes' Islands. This improved monitoring along the Princes' Islands segment, which is west of the İzmit 1999 rupture and southeast of Istanbul's city center is highlighting the location of likely rupture points for the pending Marmara earthquake. It also limits the maximum size of future events along the whole Marmara seismic gap in case of cascade behavior. Knowing this, the need of a regional earthquake early warning system for Istanbul and surroundings could be justified. The aseismic part of the Princes' Islands segment could represent a potential and likely high-slip area in a future, large earthquake. Fault characterization is likewise very relevant to determine the directivity of earthquake waves approaching Istanbul. Recently made modelling of potential impacts to Istanbul from different scenarios have shown to improve the estimation of hazards the seismic gaps pose. In a similar way, more improved and dense seismic monitoring is expected from on-going efforts to install an underground (borehole-based) seismograph network in the eastern Sea of Marmara region.[44]

Istanbul, being the most populated city in Turkey, lies right near the segments of the North Anatolian Fault Zone, making it at very high risk to an earthquake disaster which could possibly cause thousands of casualties and severe damage. Following the large earthquake in 1999, there was a great urgency for the government to mitigate these risks. With the help of organizations like the World Bank, hundreds of buildings have been retrofitted and reconstructed, and thousands of citizens have been trained in disaster preparedness.[45]

Gallery

Flooded Kavaklı Beach in Gölcük

Flooded Kavaklı Beach in Gölcük Tsunami wave causing minor surge

Tsunami wave causing minor surge Fault scarp as a result of the earthquake

Fault scarp as a result of the earthquake Surface rupture in Sakarya

Surface rupture in Sakarya Collapsed building

Collapsed building Destroyed buildings along a street

Destroyed buildings along a street Classroom where the fault rupture went right under it

Classroom where the fault rupture went right under it

See also

References

- Barka, A. (1999). "The 17 August 1999 Izmit Earthquake". Science. 285 (5435): 1858–1859. doi:10.1126/science.285.5435.1858. S2CID 129752499.

- ISC (2014), ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2009), Version 1.05, International Seismological Centre

- USGS (4 September 2009), PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey

- "Kandilli Observatory and Earthquake Research Institute". Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS) (1972). "Significant Earthquake Database" (Data Set). National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Barka, A. (2002). "The Surface Rupture and Slip Distribution of the 17 August 1999 Izmit Earthquake (M 7.4), North Anatolian Fault". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 92 (1): 376–386. Bibcode:2002BuSSA..92...43B. doi:10.1785/0120000841.

- Marza, Vasile I. (2004). "On the death toll of the 1999 Izmit (Turkey) major earthquake" (PDF). ESC General Assembly Papers, Potsdam: European Seismological Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "17 Ağustos Depremi: 1999 ve sonrasında neler yaşandı, kaç kişi hayatını kaybetti?" [17 August Earthquake: What happened in 1999 and after, how many people lost their lives?] (in Turkish). BBC News. 12 August 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "İzmit earthquake of 1999 Turkey Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- "The North Anatolian Fault Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory". www.ldeo.columbia.edu. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- Baysan, Reyhan; Saifi, Zeena; Said-Moorhouse, Lauren; Sariyuce, Isil (8 February 2023). "Emotions run high in Turkey amid questions over state response to deadly quake". CNN. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- Şengör, A. M.; Tüysüz, O.; İmren, C.; Sakınç, M.; Eyidoğan, H.; Görür, N.; Le Pichon, X.; Rangin, C. (2005). "The North Anatolian Fault: A New Look". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 33 (1): 37–112. Bibcode:2005AREPS..33...37S. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.32.101802.120415.

- Orgulu, G.; Aktar, M. (2001). "Regional Moment Tensor Inversion for Strong Aftershocks of the August 17, 1999 Izmit Earthquake (Mw =7.4)". Geophysical Research Letters. 28 (2): 371–374. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28..371O. doi:10.1029/2000gl011991. S2CID 128751123.

- Bouchon, M.; M.-P. Bouin; H. Karabulut; M. N. Toksöz; M. Dietrich; A. J. Rosakis (2001). "How Fast is Rupture During an Earthquake ? New Insights from the 1999 Turkey Earthquakes" (PDF). Geophys. Res. Lett. 28 (14): 2723–2726. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28.2723B. doi:10.1029/2001GL013112.

- OCHA (15 September 1999). "Turkey - Earthquake OCHA Situation Report No. 21". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- Gurenko, Eugene; Lester, Rodney; Mahul, Olivier; Gonulal, Serap Oguz (2006). Earthquake Insurance in Turkey: History of the Turkish Catastrophe Insurance Pool. World Bank Publications. p. 1. ISBN 9780821365847.

- Earthquake Insurance in Turkey: History of the Turkish Catastrophe Insurance Pool. World Bank Publications. 1 January 2006. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-8213-6584-7.

- "Race to find quake survivors". BBC News. 18 August 1999. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Quake rescuers race against time". BBC News. 18 August 1999. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- Ozcep, F.; Karabulut S.; Ozel O.; Ozcep T.; Imre N.; Zarif H. (2014). "Liquefaction-induced settlement, site effects and damage in the vicinity of Yalova City during the 1999 Izmit earthquake, Turkey". Journal of Earth System Science. 123 (1): 73–89. Bibcode:2014JESS..123...73O. doi:10.1007/s12040-013-0387-7. S2CID 130435029.

- Ergin, M.; Özalaybey S.; Aktar A. & Yalçin M.N. (2004). "Site amplification at Avcılar, Istanbul" (PDF). Tectonophysics. 391 (1–4): 335. Bibcode:2004Tectp.391..335E. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2004.07.021.

- "İzmit earthquake of 1999 | Turkey". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- "GSA Today - 1999 Izmit, Turkey Earthquake Was No Surprise". geosociety.org. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- Riskinin Araştırılarak Deprem Yönetiminde Alınması Gereken Önlemlerin Belirlenmesi Amacıyla Kurulan Meclis Araştırması Komisyonu Raporu Temmuz 2010

- Lusas software, "Seismic Assessment of the Mustafa Inan Viaduct"

- Scawthorn; Eidinger; Schiff, eds. (2005). Fire Following Earthquake. Reston, VA: ASCE, NFPA. ISBN 9780784407394. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- J., Scawthorn, Charles. Eidinger, John M. Schiff, Anshel (2005). Fire following earthquake. American Society of Civil Engineers. ISBN 0-7844-0739-8. OCLC 55044755.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - National Geophysical Data Center. "Tsunami event". Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Yalciner, A. C.; Synolakis, C. E.; Alpar, B.; Altinok, Y.; Imamura, F.; Tinti, S.; Ersoy, S.; Altinok, Y.; Kuran, U.; Pamukcu, S.; Kanoglu, U. (August 2011). "Field surveys and modeling 1999 Izmit tsunami". ITS 2001 Proceedings. 4 (4–6): 557–563.

- "17 August 1999, Mw 7.6, Sea of Marmara, Turkey". International Tsunami Information Center. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- "M 5.2 - 2 km NNE of Karşıyaka, Turkey". United States Geological Survey. 31 August 1999. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "M 5.9 - 4 km SE of Köseköy, Turkey". United States Geological Survey. 13 September 1999. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "M 5.2 - 8 km NNW of Ta?köprü, Turkey". United States Geological Survey. 29 September 1999. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "M 5.0 - 8 km E of Akyazı, Turkey". United States Geological Survey. 7 November 1999. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "M 5.7 - 5 km N of Sapanca, Turkey". United States Geological Survey. 11 November 1999. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "M 5.3 - 8 km E of Akyazı, Turkey". United States Geological Survey. 23 August 2000. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "M 5.0 - 24 km N of Bolu, Turkey". United States Geological Survey. 26 August 2001. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- "Komenda Miejska Państwowej Straży Pożarnej w Nowym Sączu".

- Tang, Alex K., ed. (2000). Izmit (Kocaeli), Turkey, earthquake of August 17, 1999 including Duzce Earthquake of November 12, 1999 Lifeline Performance. American Society of Civil Engineers. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-7844-0494-2.

- Greek and International Aid to Turkey

- Girgin S. (2011). "The natech events during the 17 August 1999 Kocaeli earthquake: aftermath and lessons learned". Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 11 (4): 1129–1140. Bibcode:2011NHESS..11.1129G. doi:10.5194/nhess-11-1129-2011.

- "Case study: Izmit domestic and industrial water supply project responds to a massive earthquake in Turkey". wateronline.com. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- "Bill Clinton visits İzmit, Turkey". Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- Bohnoff, M.; Bulut, F.; Dresen, G.; Malin, P. E.; Eken, T.; Aktar, M. (2013). "An earthquake gap south of Istanbul". Nature Communications. 4 (1999): 1999. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1999B. doi:10.1038/ncomms2999. PMID 23778720.

- "Preparing for the Big One: Learning from Disaster in Turkey". World Bank. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

External links

- M7.6 - western Turkey – United States Geological Survey

- 17 August 1999 Kocaeli Earthquake – The European Association for Earthquake Engineering

- Initial Geotechnical Observations of the August 17, 1999, Izmit Earthquake – National Information Service for Earthquake Engineering

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.

- ReliefWeb's main page for this event.