19th Battalion (New Zealand)

The 19th Battalion was a formation of the New Zealand Military Forces which served, initially as an infantry battalion and then as an armoured regiment, during the Second World War as part of the 2nd New Zealand Division.

| 19th Battalion (19th Armoured Regiment) | |

|---|---|

Infantry of 19th Battalion linking up with the Tobruk garrison, 27 November 1941 | |

| Active | 1939–1945 |

| Disbanded | 18 December 1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry (1939 to 1942) Armoured (1943 to 1945) |

| Size | ~760 personnel |

| Part of | 4th Brigade, 2nd Division |

| Engagements | Second World War |

The 19th Battalion was formed in New Zealand in 1939 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel J. S. Varnham. After a period of training it embarked for the Middle East and then onto Greece in 1941 as part of the 2nd New Zealand Division. It participated in the Battles of Greece and later in Crete. Evacuated from Crete, it then fought in the North African Campaign and suffered heavy losses during Operation Crusader. Brought back up to strength, the battalion participated in the breakout of the 2nd New Zealand Division from Minqar Qaim in June 1942, where it had been encircled by the 21st Panzer Division. The following month, the battalion suffered heavy casualties during the First Battle of El Alamein.

In October 1942, the battalion was converted to an armoured unit and designated 19th Armoured Regiment. To replace men lost at El Alamein, personnel were drawn from a tank brigade being formed in New Zealand. The regiment spent a year in Egypt training with Sherman tanks, before embarking for Italy in October 1943 to join the Eighth Army. It participated in the Italian Campaign, fighting in actions at Orsogna and later at Cassino. The regiment finished the war in Trieste and remained there for several weeks until the large numbers of Yugoslav partisans also present in the city withdrew. Not required for service in the Pacific theatre of operations, the regiment was disestablished in late 1945.

Formation

The 19th Battalion was formed in New Zealand in 1939 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Varnham, a veteran soldier who had commanded an infantry company during the First World War, and was the second of three infantry battalions making up the 4th Infantry Brigade.[Note 1] Its personnel were drawn from the lower half of the North Island of New Zealand and formed into Wellington, Wellington/West Coast, Hawke's Bay and Taranaki companies. Most of the battalion's personnel entered Trentham Camp on 3 October, with officers and non-commissioned officers having commenced their training the previous week.[2][3]

After completing their initial training, the battalion's 760-odd personnel departed on the liner RMS Strathaird for the Middle East on 5 January 1940 as part of the first echelon of the 2nd New Zealand Division, commanded by Major General Bernard Freyberg;[4] the 4th Brigade was one of the division's three infantry brigades.[5] The battalion arrived at its base in Maadi, Egypt on 14 February,[6] and was involved in training and garrison duty at the Baggush Box, a defensive position in the Western Desert, for most of the next 12 months.[7] Work improving the fortifications escalated in September, when the Italian Army crossed the Egyptian border and Baggush was bombed.[8] The battalion was reinforced in December with personnel from the third echelon of the 2nd New Zealand Division, which had just arrived in Egypt having spent several months in the south of England. It was then tasked with the defence of the Royal Air Force's aerodromes in the Western Desert, which called for the wide distribution of the battalion's companies.[9]

Greece

The British Government anticipated an invasion of Greece by the Germans in 1941 and decided to send troops to support the Greeks, who were already engaged against the Italians in Albania. The 2nd New Zealand Division was one of a number of Allied units dispatched to Greece in early March.[10] The 4th Brigade was tasked with the defence of the Aliakmon Line in northern Greece with the 2nd New Zealand Division positioned on the northern side of Mount Olympus. The 19th Battalion was the reserve for 4th Brigade and spent most of its time from late March to early April preparing roading and defensive positions.[11] On 6 April, the Germans invaded Greece and advanced so rapidly that their forces quickly threatened the Florina Gap. The brigade was withdrawn to the Servia Pass.[12]

The 19th Battalion was tasked with holding the mouth of the pass and spent the next few days digging in.[13] On 13 April, German Stukas bombed the battalion causing its first casualties of the war. The following day, German armour reached the Servia Pass.[14] The positions of the battalion's Wellington and Hawkes' Bay companies were the subject of an attack on the night of 14–15 April. The Germans were resolutely defeated and at dawn, 120 of them were prisoners of war and another 150 or so were killed, while the battalion's own casualties amounted to two dead.[15] During the action, the battalion's commander, Varnham, was wounded and evacuated with its second-in-command, Major Blackburn, taking over for the next two months.[16] Despite artillery fire and bombing, the battalion continued to hold up the Germans for three days before being withdrawn.[17] Its new position was at Molos, near Thermopylae, which was reached after a bombing raid killed more personnel.[18] The battalion was charged with monitoring the coast for the next few days although one company was detached during this time and sent to Thermopylae to man defensive positions there.[19]

On 24 April, the 4th Brigade was moved to Kriekouki Pass through which the entire 2nd New Zealand Division was to withdraw. The 19th Battalion was in reserve. Again a company was detached for defensive duties, this time at Corinth Canal.[20] In the early hours of 27 April, after contact with a German convoy of 100 vehicles, the brigade withdrew again,[21] this time through Athens to Porto Rafti, from where it was to be evacuated. Once in position, the 19th Battalion was held in reserve on the road, just a mile from the beach.[22] In the meantime, the company at the Corinth Canal was caught in a German attack and cut off; most became prisoners of war.[23] On the night of 29 April, and into the early hours of the following morning, the brigade was evacuated with the battalion being the last unit to embark from Porto Rafti.[24] The campaign in Greece resulted in 24 men of the battalion being killed, with 20 wounded. Nearly 150 were made prisoners of war.[25]

Crete

From Greece, the 19th Battalion was shipped to the island of Crete where it arrived on 28 April with 475 personnel.[26] Designated as the reserve battalion for 4th Brigade, it was stationed just to the east of Galatas.[27][28] By mid-May it was increasingly apparent that the Germans would mount an invasion of Crete.[29] The airborne invasion by the Germans commenced in the morning of 20 May, while many of the battalion's soldiers were eating breakfast. Most of the descending paratroopers over the area were shot as they parachuted down and their equipment integrated into the defences.[30]

A field hospital in the 18th Battalion's sector was captured by paratroopers and about 500 wounded soldiers and medical staff were made prisoners of war. When the Germans left the area, they took their prisoners. Elements of 19th Battalion came across them and after a short engagement killed the guards and freed their captives although some had inadvertently received friendly fire.[31][32] By the afternoon, it, like the neighbouring 18th Battalion, was in control of its area of responsibility and had killed or captured around 150 paratroopers.[30][33] However, a prison to the southwest was in the hands of the Germans. That evening, two companies of the battalion mounted a counterattack after a report that the paratroopers at the prison were clearing an airfield. Although supported by some light tanks, the New Zealanders became lost and the next morning were ordered to return to their defensive positions.[34] The battalion was then engaged in fighting over a hill[35] that overlooked the road to Chania, key to preventing the Germans from advancing to the town.[36]

In the afternoon of 25 May, the Germans attacked along the road from the prison, towards Galatas. After defending for two hours,[37] the 4th Brigade withdrew, with 19th Battalion temporarily being attached to the 5th Infantry Brigade, positioned to the west of Chania.[38] Two day later, while manning a rearguard defensive line at Chania, it supported a counterattack mounted by Australian and New Zealand forces in an action later known as the Battle of 42nd Street, following an advance by the 141st Mountain Regiment. The Germans were routed but the Allied forces withdrew that evening as the Germans began reinforcing their lines.[39][40]

The withdrawal was at a forced march up and over the mountains to the port town of Sphakia. The 5th Brigade was part of the rearguard, fighting delaying actions to prevent chasing Germans of the 85th Mountain Regiment from cutting the road to Sphakia.[41] The evacuation commenced on the nights of 28 and 29 May, with 19th Battalion departing on the latter date aboard Australian destroyers.[42] Its casualties during the fighting on Crete amounted to just over 60 dead, around 70 wounded and 80 made prisoners of war.[43]

North Africa

Once back in Egypt, the 19th Battalion began to receive reinforcements to bring it back up to strength and Varnham, recovered from the wounds received in Greece, resumed command.[44] By 24 June it was at its full complement although still short on equipment. Training was initially limited to route marches and lectures on the learnings of the campaigns in Greece and Crete[45] but by August it was getting re-equipped and battlefield training was underway.[46] The 2nd New Zealand Division was now preparing for a role in the upcoming Libyan offensive, and several divisional and brigade level exercises were carried out. By September, the battalion was based at the Baggush Box, building up the defences there with the rest of the 4th Brigade alongside the 6th Infantry Brigade, while also doing intensive training in open desert warfare.[47][48] During this time, Varnham was sent back to New Zealand to perform special duties. His replacement as commander of the battalion was Major S. F. Hartnell, who had been one of its company commanders.[49]

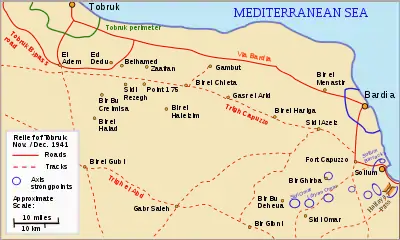

The battalion's training was in preparation for the 2nd New Zealand Division's role in the upcoming Operation Crusader, which was planned to lift the siege of Tobruk.[50] The New Zealanders were part of the 8th Army's XIII Corps, which was tasked with isolating and capturing the frontier posts held by the enemy while XXX Corps moved to the south to defeat the armour of Generalleutnant[Note 2] Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps.[52][53] At the same time, the Tobruk garrison was to attempt a breakout.[54]

Operation Crusader

The 19th Battalion began moving forward to the starting positions for Operation Crusader on 12 November, leaving just over 60 men behind around which a new battalion could be formed in the event of heavy losses.[55] The operation commenced on the night of 18 November, with the division moving forward across the Libyan border.[56] The 4th Brigade, with 19th Battalion as its reserve, cut off the road between Bardia and Tobruk on 22 November, and rounded up Italian prisoners of war. The New Zealanders were then ordered to support British armoured units of XXX Corps at Sidi Rezegh, which had suffered heavy losses from Rommel's armour. Meanwhile the outbreak from Tobruk was progressing slowly, having met with an unexpected German division.[57][58]

The 4th Brigade was tasked with advancing to Tobruk, via an escarpment linking Zaafram and Belhamed and onto Ed Duda; the 6th Brigade was to advance to Sidi Rezegh along an escarpment to the south.[59] The 19th Battalion led the brigade for part of this advance before providing flank protection during its attack on an airfield at Gambut.[60] It then was involved in the brigade's nighttime attack on 24 November which captured Zaafran.[61] The 6th Brigade in the meantime had secured Sidi Rezegh although unexpectedly strong resistance that there were many casualties.[62]

In order to break through to Tobruk, an attack on Ed Duda was mounted by 6th Brigade on the night of 25 November. This failed with heavy losses.[63] A corresponding attack on Belhamed, mounted by the 18th and 20th Battalions, was more successful although the New Zealanders were left on a ridge and exposed to heavy artillery fire.[64] The 19th Battalion had been held in reserve at Zaafran for the Belhamed attack. By this stage, it was the only full strength infantry unit left in the 4th and 6th Brigades. It was ordered to link up with the Tobruk garrison, elements of which had moved forward to take Ed Duda in light of 6th Brigade's failure to do so.[65] The plan called for the battalion to advance behind Matilda II tanks from a British armoured regiment. The attack, one of the British Army's first nighttime attacks involving both infantry and armour, was a success. The tanks scattered the enemy, and any pockets of resistant were dealt with by the following infantry. The attack was completed without any casualties among the battalion and over 500 enemy were made prisoners of war. The efforts secured a corridor through to Tobruk.[66][67]

The battalion established a defensive position in a wadi to the east of Ed Duda.[67] There they collected stray enemy soldiers as prisoners of war and were also subject to shelling.[68] The next day, the battalion was divided into two; a portion returned to Zaafran while the other remained at Ed Duda. In the meantime, pressure was building on 6th Brigade, which was now surrounded and subject to heavy artillery fire.[69] German tanks of the 15th Panzer Division overran the brigade on the afternoon of 30 November.[70] The following day, the 18th and 20th Battalions were pushed off Belhamed.[71]

After the withdrawal of 4th and 6th Brigades from Belhamed and Sidi Rezegh respectively, two companies of the 19th Battalion remained at Ed Duda, becoming part of the Tobruk defensive perimeter.[72] They remained as part of the Tobruk garrison until 11 December, when they were transported via Tobruk back to Baggush.[73] The other two companies had already returned to Baggush with the remnants of the 4th and 6th Brigades. Although the 19th Battalion was relatively intact, most of the remaining infantry battalions had suffered heavy losses. The entire division would spend the next few months in a rebuilding phase.[74]

Rebuilding

In early March 1942, the 19th Battalion moved, with the rest of the 2nd New Zealand Division, to Syria to defend against a possible attack through Turkey on the Middle East oilfields by the Germans.[75][76] Based at Zabboud, the battalion was set to work on preparing defences covering routes to the south.[77] By June, the defensive positions were largely complete and many of the battalion's soldiers were granted leave for sightseeing.[78] Then, following the attack on the Eighth Army's Gazala Line by Panzer Army Africa, the 2nd New Zealand Division was recalled to Libya. It commenced its journey from Syria on 17 June.[79]

The New Zealanders made their way to a neglected fortified position to the west of Mersa Matruh, surrounded by minefields,[80] reaching it on the night of 21 June; the battalion had travelled 900 kilometres (560 mi) in five days. It spent four days at Matruh, where it formed an anti-tank platoon equipped with a complement of 2-pounder anti-tank guns. These had been taken over from the 2nd New Zealand Division's No. 7 Anti-Tank Regiment which had just received 6-pounder guns.[81][82] Freyberg, the divisional commander, disliked the plan for his command to be based at Matruh, regarding it as a trap.[83] After the fall of Tobruk to Rommel's forces, the division was ordered on 25 June to establish defensive positions at Minqar Qaim.[81] It was to hold and delay the advance of the Panzer Army Africa for as long as it could while remaining intact.[84]

The 19th Battalion arrived at Minqar Qaim in the late afternoon of the following day, where it was positioned on the south of the division's perimeter. On the way, it was attacked by German bombers although there was only one casualty.[85] By the middle of the afternoon of 27 June, the division had been encircled by the 21st Panzer Division. German tanks and infantry approached the 2nd New Zealand Division's positions and were successfully beaten off.[86] Later in the day, Freyberg was wounded and the commander of 4th Brigade, Brigadier Lindsay Inglis, took over command of the division.[87] Prior to his wounding, Freyberg had decided that the New Zealanders were to attempt a breakout from their encirclement that night.[88]

On the south side of the New Zealand perimeter, the 19th Battalion was closest to the designated area for the breakout. Under a bright moon, the infantry marched with bayonets fixed, beginning in the early hours of 28 June before machine gun fire broke out. Many Germans were caught in a state of undress and were swiftly dealt with. Having achieved the breakthrough, transport was quickly brought up and the battalion were loaded up for the trip to the El Alamein line. Its casualties were light; 21 men were killed or died of their wounds.[89]

El Alamein

Despite the events of Minqar Qaim, the 2nd New Zealand Division was one of the most complete divisions of the Eighth Army still able to be employed along the El Alamein line.[90] The area was subject to further offensives by Panzer Army Afrika and on 14 and 15 July 1942, during the First Battle of El Alamein, the battalion was involved in an effort to assist 30 Corps, by being part in what would be known as the Battle of Ruweisat Ridge.[91]

The Italian Brescia and Pavia divisions, along with elements of the 15th Panzer Division, held Ruweisat Ridge, which was in the centre of the El Alamein line, and dominated the surrounding area. The 4th Brigade was to take the western end of the ridge, with Brigadier Howard Kippenberger's 5th Brigade tasked with the capture of the centre of the ridge. The 5th Indian Brigade was allocated to deal with the eastern end. British tanks, in the form of two armoured brigades, were to protect the flanks and be in support to deal with the expected counterattack.[91]

After a night-time advance of over 6 miles,[91] the 19th Battalion was positioned on the ridge. Its ranks had increased with the presence of 60 soldiers from 18th Battalion who had become separated from their unit during the advance.[92] The brigade's move forward had routed much of the Italian defences although, on daybreak, it was discovered that numerous strong points had been bypassed, leaving the German line in front of the ridge largely intact.[93] The 5th Brigade was also on the ridge but was widely dispersed. Its advance had skirted a regiment of panzers, which in the early hours of the morning of 15 July routed the flanking battalion of the 5th Brigade. This left the battalions of the 4th Brigade even more exposed and receiving fire from the enemy.[94][95] The Indians were likewise in position having secured their objective.[96]

The battalion's infantry struggled to dig good defensive positions, with rock encountered just beneath the surface. A counterattack by elements of the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions was launched in the afternoon of 15 July. The limited number of anti-tank guns present were exposed and quickly became immobilised or had to withdraw. This left the infantry of the 4th Brigade to be surrounded and large numbers were forced to surrender. The 20th Battalion was overrun first, with some of its personnel making it to the positions of 19th Battalion. It too became surrounded. By nightfall, the brigade had been overrun and 1,100 soldiers, many from 19th Battalion, were taken prisoner. Among them was Hartnell, although he was able to escape when night fell and make his way back to the Allied lines. The British tanks belatedly moved forward and although this drove off the German armour, the other infantry brigades withdrew from Ruweisat Ridge later in the evening.[97][98][99]

Of the battalions of 4th Brigade, only 18th Battalion had sufficient strength to remain in the field.[100] Its commander had received fatal wounds at Ruweisat Ridge and an officer of 19th Battalion, Major Clive Pleasants, took over.[101] The losses suffered by the 19th and 20th Battalions saw them withdrawn to Maadi to recover and reequip.[100]

Conversion to armour

It had previously been decided to form an armoured brigade to provide tank support to the 2nd New Zealand Division and as a result, the 1st New Zealand Army Tank Brigade was formed in July 1941. This brigade was still undergoing training in New Zealand in September 1942 when it was decided to convert the 4th Brigade, still refitting at Maadi, while the 5th and 6th Brigades continued to campaign in Egypt. The brigade still in New Zealand was broken up to provide reinforcements for the division.[102][103]

At the time, the 19th Battalion had 600 personnel but later in the month nearly 200 were transferred to infantry battalions and the remainder informed of the pending conversion to armour. On 5 October 1942, the battalion was officially designated 19th Armoured Regiment[104] and the following month, its ranks were increased with personnel from the 3rd Army Tank Battalion, newly arrived from New Zealand.[105] In December, a pair of Covenanters and a Crusader tank was provided to the regiment for training[106] but one of these was soon lost in a live firing exercise.[107] The two remaining tanks were rostered to the squadrons for practical training for two day periods until April 1943, when the regiment began receiving the M4 Sherman tanks that were to be its operational complement. At about the same time, its commander, Hartnell, was promoted to brigadier and appointed second in command of the 4th Armoured Brigade and was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel R. McGaffin. The new commander had experience with armour, having commanded the 3rd Army Tank Battalion when it was formed in New Zealand.[108]

The war in North Africa had concluded in May with the defeat of Axis forces in Tunisia, so a new operational role for the 2nd New Zealand Division was required. Consideration was given to transferring it to the Pacific but once the New Zealand Government decided that the division would stay in Europe, it joined the Eighth Army, which was now engaged in the Italian campaign.[109] The regiment embarked for Italy in early October,[104] having only reached full strength the previous month.[110]

Italy

The regiment disembarked at Taranto on 22 October[111] and early the following month were reunited with its tanks, these having been transported separately.[112] As the New Zealanders advanced towards the Sangro, the 19th Regiment, in the lead, was detached to support the 19th Indian Brigade in an operation at Perano, on 18 November 1943. The town was believed to be lightly held but the operation was compromised by orders to not use wireless for communication. This was to avoid the Germans detecting the presence of the 2nd New Zealand Division in Italy.[113] Instead of the light opposition that was expected, A Squadron, which was composed of 14 Sherman tanks, encountered elements of the 16th Panzer Division. The Indians secured their objective but the clash with the Germans resulted in four Shermans being destroyed and seven of the squadron's personnel killed. Before the Germans withdrew, they had scavenged papers from one of the destroyed tanks which alerted them to the fact that the New Zealanders were now in Italy.[114][115]

Orsogna

Later in the month, the division crossed the Sangro with a view to taking the high ground beyond, a series of ridges culminating in one peaked by the town of Orsogna.[116] Initial attacks on Orsogna in the first week of December involved infantry, and then the tanks of 18th Regiment; these failed as did subsequent attempts mounted later in the month.[117] As a stalemate settled, the infantry of the 2nd New Zealand Division remained active around Orsogna with the 19th Regiment being based at Sfasciata Ridge and providing support as mobile artillery. It would spend the winter months in this role, with one squadron at a time rotated out as a reserve every eight days.[118][119]

There was still the occasional need for a foray to be made by the regiment's tanks. Over the first two weeks of January 1944, C Squadron was operating in assistance of a flanking battalion of paratroopers at Poggiofiorito while B Squadron was making long range shoots in aid of the 28th Battalion.[120] On 15 January, the regiment, along with the rest of the division, began to withdraw from the Orsogna sector. It rested for two weeks at Piedimonte on the western side of the Apennines in preparation to join the fighting in the sector of the 5th Army.[119][121]

Cassino

In February, the 2nd New Zealand Division was transferred to the 5th Army and, as part of the newly formed New Zealand Corps to be commanded by Freyberg, took responsibility from the United States II Corps for the Cassino section of the Gustav Line. For the previous few weeks, the strategically important town of Cassino, controlling the entrance to the Liri Valley and overlooked by the mountain of Monte Cassino, had been under attack by the American forces but remained in the hands of the Germans.[122][123]

The New Zealand Corps took responsibility for the sector on 12 February.[124] The 19th Regiment was involved in the first attack mounted by the New Zealand forces on the town, on 17 February, following the 28th Battalion which had secured a bridgehead across the Rapido River. However, the tanks never got started. Engineering work had not been completed in time on a railway embankment that led into the town and the tanks were unable to move in. Shelled while waiting, they suffered 12 casualties before withdrawing back to Mignano, from where they had started their advance.[125][126]

The regiment was tasked with supporting a further attempt on the town, this time involving the 6th Brigade, the objective being to secure a bridgehead to be exploited by the other regiments of the 4th Armoured Brigade. Poor weather delayed the start of the attack by three weeks.[127][128] On 15 March, Cassino was bombed, followed by an artillery bombardment after which B Squadron moved into the town behind the infantry of 25th Battalion. However, the tanks were unable to keep up with the soldiers as they moved forward and this affected their ability to provide the desired support. The Germans defended strongly, assisted by the rubble that hampered the easy movement of the tanks. This dashed hopes of a quick break through.[129][130] Instead the tank crews disembarked and using tools, cleared spaces for their Shermans to be well positioned for providing cover for the infantry.[131] In the evening, A Squadron and a troop from C Squadron moved in to support the 26th Battalion, which reinforced the 25th Battalion.[132][133]

Little progress was made over the coming days, and several tanks became disabled and lost in the rubble in their efforts supporting the attacks made by the New Zealand infantry.[134] The two infantry brigades of the 2nd New Zealand Division were withdrawn from Cassino in early April and sent to the Apennines but the 4th Armoured Brigade remained in place, under the command of the 6th British Armoured Division which now had responsibility for the sector. The New Zealand regiments provided indirect artillery support during this time.[135] The Allied forces began preparing for a major offensive against the Gustav Line. This commenced on 11 May,[136] and then, on short notice, the 19th Regiment was attached to the British 4th Infantry Division. It was to support that division's operations against Cassino. The regiment moved up on the night of 13 May and went into action the next day.[137] Further engagements followed over the next few days, during which two tanks of B Squadron were lost, before Cassino was captured on 18 May. The regiment then returned to the control of the 2nd New Zealand Division.[138]

Advance to Florence and beyond

The 2nd New Zealand Division was withdrawn from action in mid-June and remained in reserve, recuperating after the efforts of the previous few months, until 9 July, when it was attached to XIII Corps.[139][140] They were to lead the advance to Florence.[141] In the approach to the Paula Line, less than 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Florence, there were a series of small-scale actions, with the tanks of the 4th Armoured Brigade supporting the attacking infantry, as the German defenders fought a delaying withdrawal on the approach to the town.[142] In one such engagement, on 29 July, one of the regiment's tank troops supported 24th Battalion in its attack on San Michele, in the Tuscan hills.[143] After hectic fighting as a result of a German counterattack, the Shermans, of which only two were still mobile, had to withdraw in order to fix faults that had developed with their guns.[144] The Paula Line was breached on 4 August and Florence captured the same day.[145]

In August, Lieutenant Colonel A. Everist took command of the regiment after McGaffin was appointed second-in-command of 4th Armoured Brigade.[146] Everist had been a company commander with the unit prior to the regiment's conversion to armour.[147] The division was tasked with participating in the Adriatic offensive, which aimed to break the Gothic Line.[148] In preparation for the forthcoming action, the regiment's tanks were overhauled at its temporary base of operations at Iesi.[149] The offensive commenced on 12 September, with the 2nd New Zealand Division attacking the Coriano Ridge.[150] The regiment's involvement began with C Squadron assisting in an engagement mounted by a Greek brigade at Rimini Airfield.[151] It then pushed on, accompanied by 22nd Battalion, fording the Marecchia River on 22 September.[152] Progress was slow thereafter as it advanced into the Po valley.[153]

On 19 and 20 October, the 4th Armoured Brigade was involved in its first and only action as a brigade in an attack towards the Savio River. This was primarily a tank action, in contrast to previous battles in which the armour supported the infantry. The attack, which saw two of the regiment's squadrons being covered by 24th and 25th Battalions while the third, C Squadron, was part of an artillery shoot covering a crossing by Canadian units, was a success and pushed the Germans across the Savio. However, progress had been slower than expected due to poor weather and muddy conditions.[154][155]

Winter months

The 2nd New Zealand Division was then sent into reserve on 22 October for a rest.[153] In the first week of November, Everist left the 19th Regiment to return to New Zealand on furlough. His replacement as commander was Lieutenant Colonel H. H. Parata,[156] who had previously served with the regiment for a twelve-month period from July 1943.[157] The regiment returned to the front, based at Faenza to support the crossing of the Senio River.[158] It began providing artillery support on 20 December, with B Squadron forming a gunline along the Senio and engaging spotted targets; it would expend over 12,000 rounds in this duty, which it performed until 6 January 1945.[158] The regiment remained at Faenza for several weeks, with one squadron forward on the Senio, providing targeted shoot in response to infantry requests, and another guarding the road behind the crossing.[159] The squadrons rotated out on a regular basis back to Faenza.[160]

By February 1945, the infantry picked up the intensity of their patrolling and the regiment's squadrons were more frequently called up to lay down fire on targets identified as being of interest.[160] They also began to receive the Sherman Firefly, which mounted a 17-pounder anti-tank gun, each troop allocated one of these tanks.[161] In early March, the division was withdrawn from the Senio front for a rest on the Adriatic coast, with the 19th Regiment settling in at Cesenatico.[162]

Resuming the advance

After its rest, the 19th Regiment returned to the front lines in early April with Everist was back in command, having returned from his furlough to New Zealand.[163] At this time, the 2nd New Zealand Division was part of the Eighth Army's V Corps, which was mounting a renewed offensive.[164] Along with the 20th Regiment, on the night of 10 April, it supported the New Zealand infantry's crossing of the Santerno River.[165] This was followed by the crossing of the Scolo Correcchio a few days later. One troop encountered a Panther tank, which knocked out the commander's Sherman. In turn the Panther was destroyed by the troop's Firefly.[166]

The Sillaro River was crossed on 14 April, with all three squadrons heavily engaged in the support of the 9th Infantry Brigade. Two tanks were lost. By this time, the 2nd New Zealand Division was at the vanguard of the Eighth Army's advance and it was transferred from V Corps back to XIII Corps, which was thrusting to the northwest of the country.[167][168] From 18 to 19 April, the Gaiana River, defended by the 4th Parachute Division, was the regiment's focus.[169] Once the defence was overcome, the regiment resumed its advance but was then subject to a friendly fire incident, when the leading troop was bombed by Supermarine Spitfires. A two-day rest followed before it rejoined the advance.[170] The Po was crossed by the infantry without incident on 24 April, although congestion with other traffic of V Corps meant it was a few days before the 19th Regiment was able to traverse the river.[171] The regiment's headquarters section crossed first with C Squadron on 29 April and proceed to cross the Adige as well. The other squadrons went over the Po the next day.[172]

Trieste

By 1 May German resistance was fading and only isolated pockets provided resistance as the New Zealanders moved towards Venice. The headquarters section and C Squadron, still separate from the rest of the regiment, gained the town of Sistiana on 2 May and were then ordered to advance to Trieste, where Yugoslav Partisans had partial control of the city. On the approach and in sections of Trieste, the New Zealanders had to deal with diehard enemy elements which refused to surrender.[172] One such group was holed up in the city's courthouse and C Squadron's tanks put several cannon shots into the building allowing the partisans entry to destroy the German garrison.[173]

The war ended shortly afterwards but the 2nd New Zealand Division remained in Trieste for several weeks until the large numbers of Yugoslav partisans also present in the city withdrew.[174] With the war over, long serving personnel left for New Zealand while the regiment moved to Florence to winter.[175] A group of personnel remained near Trieste to help with the transport of its Shermans to Bologna before rejoining the rest of the regiment in September.[176] Not required for service in the Pacific theatre of operations, the regiment was disestablished in November 1945. By then most its personnel had already departed. Some went on to join J Force, the New Zealand contingent to serve in Japan on occupation duties, while the rest returned to New Zealand.[177]

During the war, the 19th Battalion and its successor, the 19th Armoured Regiment, lost nearly 230 officers and men either killed in action or who later died of their wounds, including 34 men who died as prisoners of war. Nearly 490 personnel were made prisoners of war.[43]

Honours

Four members of the battalion, including three of its commanders,[Note 3] were awarded the Distinguished Service Order while a member of the YMCA who was attached to the battalion for a portion of its service overseas was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire. Twelve officers were awarded the Military Cross while two others received the United States Bronze Star and the Greek Military Cross respectively. One soldier received the Distinguished Conduct Medal and 20 others the Military Medal. Numerous men, including the founding commander of the battalion, were mentioned in dispatches.[178]

The 19th Battalion and its successor, the 19th Armoured Regiment, was awarded the following battle honours:

Mount Olympus, Servia Pass, Olympus Pass, Elasson, Molos, Greece 1941, Crete, Maleme, Galatas, Canea, 42nd Street, Withdrawal to Sphakia, Middle East 1941–44, Tobruk 1941, Sidi Rezegh 1941, Sidi Azeiz, Belhamed, Zemla, Alam Hamza, Mersa Matruh, Minqar Qaim, Defence of Alamein Line, Ruweisat Ridge, El Mreir, Alam el Halfa, North Africa 1940–42, Perano, The Sangro, Castel Frentano, Orsogna, Cassino I, Cassino II, Gustav Line, Advance to Florence, Cerbaia, San Michele, Paula Line, St. Angelo in Salute, Pisciatello, Bologna, Sillaro Crossing, Gaiana Crossing, Italy 1943–45.[179][Note 4]

Commanding officers

The following officers served as commanding officer of the 19th Battalion:[180]

- Lieutenant Colonel F. S. Varnham (October 1939–April 1941; June–October 1941);[Note 5]

- Major C. A. D'A. Blackburn (April–June 1941);

- Lieutenant Colonel S. F. Hartnell (October 1941–April 1943);[Note 6]

- Lieutenant Colonel R. L. McGaffin (April 1943–August 1944);

- Lieutenant Colonel A. M. Everist (August–November 1944; March–December 1945);

- Lieutenant Colonel H. H. Parata (November 1944–March 1945).

Notes

- Footnotes

- The other two infantry battalions were the 18th and 20th.[1]

- The rank of generalleutnant is equivalent to that of major general in the United States Army.[51]

- Hartnell, Everist, and McGaffin.[178]

- The battle honours awarded for its work as an infantry battalion were entrusted to the Wellington Regiment, The Wellington West Coast and Taranaki Regiment, and The Hawke's Bay Regiment. Those awarded to the 19th Armoured Regiment are entrusted to Queen Alexandra's Regiment.[179]

- Varnham later achieved the rank of brigadier.[2]

- Hartnell later achieved the rank of brigadier.[181]

- Citations

- Sinclair 1954, p. 16.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 2.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 33–34.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 8.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 3–4.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 14–15.

- McGibbon 2000, pp. 263–265.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 37.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 47.

- McClymont 1959, p. 103.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 64–65.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 68–69.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 70–71.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 75–76.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 81–82.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 85.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 87–88.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 89–90.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 91.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 93.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 94–95.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 337–338.

- McClymont 1959, p. 419.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 100–101.

- McClymont 1959, p. 487.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 111–112.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 113.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 140–141.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 126.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 130–132.

- Palenski 2013, p. 84.

- Filer 2010, pp. 66–67.

- Filer 2010, p. 66.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 145.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 158.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 141.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 167.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 169.

- Palenski 2013, pp. 123–125.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 171–172.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 172–174.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 176–177.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 548.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 176.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 177.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 181.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 197.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 186–187.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 190.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 192–193.

- Mitcham 2007, p. 197.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 205.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 195–196.

- McGibbon 2000, p. 389.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 192–193.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 207–208.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 207–210.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 197–199.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 214.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 199–200.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 223.

- Cox 2015, pp. 100–102.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 225–226.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 227–229.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 206–207.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 230–231.

- Cox 2015, pp. 98–100.

- Cox 2015, pp. 112–113.

- Cox 2015, p. 115.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 244–245.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 246.

- Cox 2015, p. 137.

- Cox 2015, p. 151.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 252–253.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 260.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 236.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 240.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 249–250.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 263–264.

- Scoullar 1955, pp. 52–54.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 266–267.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 254.

- Scoullar 1955, pp. 55–56.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 269.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 256.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 270–271.

- Cameron 2006, p. 80.

- Cameron 2006, p. 133.

- Cameron 2006, pp. 137–140.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 282.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 293–294.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 286.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 296–299.

- Scoullar 1955, pp. 269–270.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 300.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 302.

- Scoullar 1955, pp. 288–290.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 305–308.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 292–293.

- Scoullar 1955, pp. 310–311.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 317.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 303–304.

- McGibbon 2000, p. 37.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 304–305.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 311–312.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 305.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 310.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 311–313.

- McGibbon 2000, p. 248.

- Plowman 2010, p. 15.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 321–322.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 3326.

- Plowman 2010, pp. 27–28.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 402.

- Plowman 2010, p. 34.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 403.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 412–415.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 358–359.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 417–421.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 360–361.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 362–363.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 367–368.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 424.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 427.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 370.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 434.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 371–372.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 442.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 374.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 449–450.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 376.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 377.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 454.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 458–459.

- Kay 1967, pp. 11–13.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 469–470.

- Kay 1967, p. 27.

- Kay 1967, pp. 32–34.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 471–475.

- McGibbon 2000, p. 251.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 479.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 482–483.

- Pugsley 2014, pp. 484–485.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 487.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 495.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 439.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 199.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 442.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 444–445.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 447.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 448–449.

- Kay 1967, pp. 231–235.

- Kay 1967, p. 279.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 505.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 471–473.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 475.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 341.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 478.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 482–483.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 484–486.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 487.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 488.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 489–491.

- Kay 1967, p. 396.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 527.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 495–496.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 529.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 498–499.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 499–500.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 508–509.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 511–512.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 513–516.

- Pugsley 2014, p. 539.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 517–520.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 524–525.

- Kay 1967, pp. 571–572.

- Sinclair 1954, pp. 526–527.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 549.

- Mills, T.F. "19th Armoured Regiment, 2NZEF". www.regiments.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 551.

- Sinclair 1954, p. 54.

References

- Cameron, Colin (2006). Breakout Minqar Qaim, North Africa 1942. Christchurch: Willson Scott Publishing. ISBN 0-9582631-3-2.

- Cox, Peter (2015). Desert War: The Battle of Sidi Rezegh. Auckland: Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921966-70-5.

- Filer, David (2010). Crete: Death From the Skies. Auckland, New Zealand: David Bateman. ISBN 978-1-86953-782-1.

- Kay, Robin (1967). Italy, Volume II: From Cassino to Trieste. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington, New Zealand: Historical Publications Branch. OCLC 173284646.

- McClymont, W. G. (1959). To Greece. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington, New Zealand: War History Branch. OCLC 4373298.

- McGibbon, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History. Auckland, New Zealand: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558376-0.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2007). German Order of Battle, Volume Three: Panzer, Panzer Grenadier, and Waffen SS Divisions in WWII. Mechanicsburg, PA, United States: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3438-7.

- Palenski, Ron (2013). Men of Valour: New Zealand and the Battle for Crete. Auckland, New Zealand: Hodder Moa. ISBN 978-1-86971-305-8.

- Plowman, Jeffrey (2010). Orsogna: New Zealand's First Italian Battle. Christchurch: Willson Scott Publishing. ISBN 978-1877-42-7-329.

- Pugsley, Christopher (2014). A Bloody Road Home: World War Two and New Zealand's Heroic Second Division. Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-143-57189-6.

- Scoullar, J. L. (1955). Battle for Egypt: The Summer of 1942. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: War History Branch. OCLC 2999615.

- Sinclair, D. W. (1954). 19 Battalion and Armoured Regiment. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington, New Zealand: War History Branch. OCLC 173284782.