2–3–4 tree

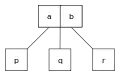

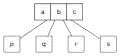

In computer science, a 2–3–4 tree (also called a 2–4 tree) is a self-balancing data structure that can be used to implement dictionaries. The numbers mean a tree where every node with children (internal node) has either two, three, or four child nodes:

- a 2-node has one data element, and if internal has two child nodes;

- a 3-node has two data elements, and if internal has three child nodes;

- a 4-node has three data elements, and if internal has four child nodes;

2-node

2-node 3-node

3-node 4-node

4-node

| 2–3–4 tree | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | tree | |||||||||||||||

| Time complexity in big O notation | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

2–3–4 trees are B-trees of order 4;[1] like B-trees in general, they can search, insert and delete in O(log n) time. One property of a 2–3–4 tree is that all external nodes are at the same depth.

2–3–4 trees are isomorphic to red–black trees, meaning that they are equivalent data structures. In other words, for every 2–3–4 tree, there exists at least one and at most one red–black tree with data elements in the same order. Moreover, insertion and deletion operations on 2–3–4 trees that cause node expansions, splits and merges are equivalent to the color-flipping and rotations in red–black trees. Introductions to red–black trees usually introduce 2–3–4 trees first, because they are conceptually simpler. 2–3–4 trees, however, can be difficult to implement in most programming languages because of the large number of special cases involved in operations on the tree. Red–black trees are simpler to implement,[2] so tend to be used instead.

Properties

- Every node (leaf or internal) is a 2-node, 3-node or a 4-node, and holds one, two, or three data elements, respectively.

- All leaves are at the same depth (the bottom level).

- All data is kept in sorted order.

Insertion

To insert a value, we start at the root of the 2–3–4 tree:

- If the current node is a 4-node:

- Remove and save the middle value to get a 3-node.

- Split the remaining 3-node up into a pair of 2-nodes (the now missing middle value is handled in the next step).

- If this is the root node (which thus has no parent):

- the middle value becomes the new root 2-node and the tree height increases by 1. Ascend into the root.

- Otherwise, push the middle value up into the parent node. Ascend into the parent node.

- Find the child whose interval contains the value to be inserted.

- If that child is a leaf, insert the value into the child node and finish.

Example

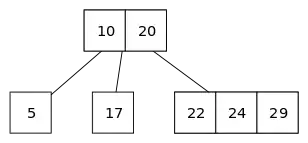

To insert the value "25" into this 2–3–4 tree:

- Begin at the root (10, 20) and descend towards the rightmost child (22, 24, 29). (Its interval (20, ∞) contains 25.)

- Node (22, 24, 29) is a 4-node, so its middle element 24 is pushed up into the parent node.

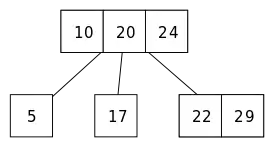

- The remaining 3-node (22, 29) is split into a pair of 2-nodes (22) and (29). Ascend back into the new parent (10, 20, 24).

- Descend towards the rightmost child (29). (Its interval (24, ∞) contains 25.)

- Node (29) has no leftmost child. (The child for interval (24, 29) is empty.) Stop here and insert value 25 into this node.

Deletion

The simplest possibility to delete an element is to just leave the element there and mark it as "deleted", adapting the previous algorithms so that deleted elements are ignored. Deleted elements can then be re-used by overwriting them when performing an insertion later. However, the drawback of this method is that the size of the tree does not decrease. If a large proportion of the elements of the tree are deleted, then the tree will become much larger than the current size of the stored elements, and the performance of other operations will be adversely affected by the deleted elements.

When this is undesirable, the following algorithm can be followed to remove a value from the 2–3–4 tree:

- Find the element to be deleted.

- If the element is not in a leaf node, remember its location and continue searching until a leaf, which will contain the element's successor, is reached. The successor can be either the largest key that is smaller than the one to be removed, or the smallest key that is larger than the one to be removed. It is simplest to make adjustments to the tree from the top down such that the leaf node found is not a 2-node. That way, after the swap, there will not be an empty leaf node.

- If the element is in a 2-node leaf, just make the adjustments below.

Make the following adjustments when a 2-node – except the root node – is encountered on the way to the leaf we want to remove:

- If a sibling on either side of this node is a 3-node or a 4-node (thus having more than 1 key), perform a rotation with that sibling:

- The key from the other sibling closest to this node moves up to the parent key that overlooks the two nodes.

- The parent key moves down to this node to form a 3-node.

- The child that was originally with the rotated sibling key is now this node's additional child.

- If the parent is a 2-node and the sibling is also a 2-node, combine all three elements to form a new 4-node and shorten the tree. (This rule can only trigger if the parent 2-node is the root, since all other 2-nodes along the way will have been modified to not be 2-nodes. This is why "shorten the tree" here preserves balance; this is also an important assumption for the fusion operation.)

- If the parent is a 3-node or a 4-node and all adjacent siblings are 2-nodes, do a fusion operation with the parent and an adjacent sibling:

- The adjacent sibling and the parent key overlooking the two sibling nodes come together to form a 4-node.

- Transfer the sibling's children to this node.

Once the sought value is reached, it can now be placed at the removed entry's location without a problem because we have ensured that the leaf node has more than 1 key.

Deletion in a 2–3–4 tree is O(log n), assuming transfer and fusion run in constant time (O(1)).[3][5]

Parallel operations

Since 2–3–4 trees are similar in structure to red–black trees, parallel algorithms for red–black trees can be applied to 2–3–4 trees as well.

See also

References

- Knuth, Donald (1998). Sorting and Searching. The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 3 (Second ed.). Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-89685-0.. Section 6.2.4: Multiway Trees, pp. 481–491. Also, pp. 476–477 of section 6.2.3 (Balanced Trees) discusses 2–3 trees.

- Sedgewick, Robert (2008). "Left-Leaning Red–Black Trees" (PDF). Left-Leaning Red–Black Trees. Department of Computer Science, Princeton University.

- Ford, William; Topp, William (2002), Data Structures with C++ Using STL (2nd ed.), New Jersey: Prentice Hall, p. 683, ISBN 0-13-085850-1

- Goodrich, Michael T; Tamassia, Roberto; Mount, David M (2002), Data Structures and Algorithms in C++, Wiley, ISBN 0-471-20208-8

- Grama, Ananth (2004). "(2,4) Trees" (PDF). CS251: Data Structures Lecture Notes. Department of Computer Science, Purdue University. Retrieved 2008-04-10.