239th Rifle Division

The 239th Rifle Division was formed as an infantry division of the Red Army after a motorized division of that same number was reorganized in the first weeks of the German invasion of the Soviet Union. It was based on the shtat (table of organization and equipment) of July 29, 1941, and remained forming up and training in Far Eastern Front until early November when the strategic situation west of Moscow required it to be moved by rail to Tula Oblast where it became encircled in the last throes of the German offensive and suffered losses in the following breakout. When Western Front went over to the counteroffensive in the first days of December the division was in the second echelon of 10th Army and took part in the drive to the west against the weakened 2nd Panzer Army. As the offensive continued it took part in the fighting for Belyov and Sukhinichi before being subordinated to the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps in January 1942 to provide infantry support. It then became involved in the complicated and costly battles around the Rzhev salient as part of 50th, 10th and 31st Armies until December. It was then moved north to Volkhov Front, and took part in several operations to break the siege of Leningrad, mostly as part of 2nd Shock and 8th Armies. As part of 59th Army it helped to drive Army Group North away from the city and was rewarded with the Order of the Red Banner in January 1944. During the following months it continued to advance through northwestern Russia but was halted by the defenses of the Panther Line in April. The division took part in the advance through the Baltic states in the summer of 1944 but in February 1945 it was transferred to 1st Ukrainian Front, rejoining 59th Army as part of 93rd Rifle Corps and fought in upper Silesia. In the last weeks of the war the 239th was advancing on Prague, but despite its distinguished record it was selected as one of the many divisions to be disbanded during the summer of 1945.

| 239th Motorized Division (March 1941 – July 12, 1941) 239th Rifle Division (July 12, 1941 – July 1945) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1941–1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Red Army |

| Type | Division |

| Role | Motorized Infantry, Infantry |

| Engagements | Battle of Moscow Tula offensive operation First Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive operation Operation Mars Operation Iskra Mga offensive Leningrad–Novgorod offensive Baltic offensive Riga offensive (1944) Battle of Memel Upper Silesian offensive Prague offensive |

| Decorations | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. Gayk Oganesovich Martirosyan Maj. Gen. Pyotr Nikolaevich Chernyshov Maj. Gen. Sergei Borisovich Kozachek Col. Aleksandr Yakovlevich Ordanovskii Maj. Gen. Vladimir Stepanovich Potapenko |

239th Motorized Division

The division began forming in March 1941 as part of the prewar buildup of Soviet mechanized forces, in the 1st Red Banner Army of the Far Eastern Front as part of the 30th Mechanized Corps. Its main order of battle was intended to be as follows:

- 813th Motorized Rifle Regiment

- 817th Motorized Rifle Regiment

- 122nd Tank Regiment

- 688th Howitzer Artillery Regiment

- Antitank Battalion

- Antiaircraft Battalion

- Reconnaissance Battalion

- Sapper Battalion[1]

Col. Gayk Oganesovich Martirosyan was appointed to command of the division on March 10 and would remain in this position after it was converted to a regular rifle division. The 30th Mechanized also contained the 58th and 60th Tank Divisions and the 29th Motorcycle Regiment.[2] On June 22 the 239th was stationed at Iman; in his memoirs Colonel Martirosyan stated that a large part of the division's cadre was recruited from Novosibirsk and Krasnoyarsk. On July 12 it left 30th Mechanized to come under direct command of 1st Army and begin converting.[3] The 122nd Tank Regiment and most of the division's motor vehicles were used to form the basis of the 112th Tank Division.[4]

Formation

The conversion required the addition of another rifle regiment and numerous other changes. When completed its order of battle was as follows:

- 511th Rifle Regiment

- 813th Rifle Regiment

- 817th Rifle Regiment

- 688th Artillery Regiment[5]

- 3rd Antitank Battalion

- 497th Reconnaissance Company

- 406th Sapper Battalion

- 614th Signal Battalion (later 614th Signal Company)

- 388th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 219th Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Company (later 189th)

- 95th Motor Transport Company

- 338th Field Bakery (later 1009th)

- 148th Divisional Veterinary Hospital (later 241st)

- 332nd Field Postal Station

- 333rd Field Office of the State Bank

The division continued forming up and training in Far Eastern Front into the first days of November, although it had received orders to prepare to be moved west as early as October 17. It was offloaded at Kuibyshev, where most of the Soviet government had been evacuated from Moscow, and paraded in the central square on November 7 in honor of the 24th anniversary of the October Revolution. After re-embarking the division entered the active army on November 8 when it arrived at Uzlovaya in Tula Oblast, southeast of Moscow,[6] where it was assigned to 3rd Army.

Tula Defensive Operation

Almost immediately after offloading, the division was involved in a running battle alongside the 413th Rifle Division and the 32nd Tank Brigade against the spearheads of the 2nd Panzer Army north and south of Tula. Although the attack was unsuccessful, it caused consternation and delay within the German command. During further fighting on November 17, led by the 239th and the 32nd Tanks, elements of the 112th Infantry Division, which lacked antitank weapons that could counter T-34 tanks, broke and ran and had to be rescued by the 167th Infantry Division, an unprecedented situation in the German army during WWII.[7]

Soon after, on November 19 the 239th was successfully fighting off attacks by a German infantry division and cavalry regiment along the line Zareche–Cheremukhovka–Durovka–Velmino–Smorodino. The next day it was re-assigned to 50th Army and was attempting to hold along a line from Kostornya to Shakhovskoe to Donskoi and Dubovoe. In connection with a breakthrough on the 299th Rifle Division's front, it began falling back to the north under pressure from tank units of 2nd Panzer Army. Following the fighting in the Stalinogorsk area, on November 23-24 the division was encircled by up to two German infantry divisions, plus tanks, and from 1600 hours on November 25 began to fall back to the northeast, having lost contact with the 50th Army's headquarters.[8] By the end of the month the division had been pulled back into the reserves of Western Front.[9]

Tula Offensive Operation

On December 6 10th (Reserve) Army became active and was subordinated to Western Front, just as that Front was going over to the counteroffensive against Army Group Center. It consisted of the 325th, 323rd, 324th, 328th, 322nd, 326th and 330th Rifle Divisions, plus the 239th, which was added to its command, and three cavalry divisions. On the previous day the Army's commander, Lt. Gen. F. I. Golikov, had received a preliminary directive from the Front:

The 10th Reserve Army is to launch its main attack in the direction of Mikhaylov and Stalinogorsk from its jumping-off point in the area of Zakharovo and Pronsk. A division-sized supporting attack from the Zaraysk and Kolomna area will move through Serebryanye Prudy in the direction of Venyov and Kurakovo.

The beginning of the offensive from the jumping-off point is slated for the morning of December 6.

Overall, the Army was deployed along a frontage about 100km in width.[10]

Golikov chose to retain the 239th as his Army reserve, with the task of reaching the area Durnoe–Telyatniki by the end of December 6. The German 29th and 10th Motorized Divisions were determined to be in the areas of Serebryanye Prudy and Mikhaylov, while units of the 18th Panzer Division were located further south, and the 112th Infantry Division was also operating along the Army's front. By December 7 the divisions of 2nd Panzer Army, which had advanced to the north and east of Tula, began to fall back; Serebryanye Prudy and Mikhaylov were liberated while the German forces were swiftly falling back on Stalinogorsk under pressure from 50th Army and 1st Guards Cavalry Corps. The advance continued and on December 13 the 239th, still in the Army's second echelon, reached the area Sukhanovo–Buchalki–Krasnoe.[11]

The second phase of the offensive began that day when the Front issued Directive No. 0106/op which laid down the following task for 10th Army: launch its main blow in the direction of Bogoroditsk, Plavsk, and Arsenevo and, in cooperation with the 1st Guards Cavalry, to destroy the German grouping in the area Uzlovaya–Bogoroditsk–Plavsk by the end of December 16. The Plava River and Plavsk itself were reached by December 18 but the desired encirclement was not achieved. The 239th was on the march and by the end of December 20 its leading elements were passing through Sorochinka as the 324th Division moved into the Army's second echelon. The German grouping was withdrawing to the Oka River in an effort to establish a strongpoint at Belyov. This town, along with Kozelsk, Sukhinichi, Kirov and Lyudinovo, were the Army's objectives in the next phase. General Golikov planned to quickly seize Belyov before pursuing in the direction of Sukhinichi. By the latter half of December 24 the division was concentrated in the area of Odoevo and was tasked with reaching the Oka the next day in the area of Moshchena.[12]

Battle for Belyov

By the end of December 25 the 322nd Division had begun fighting on the approaches to Belyov, and by the end of the next day the 239th was on the west bank of the Oka, north of the town, near Kryukovka and Zenovo. To this point the 10th Army had covered a distance of about 220km in the 20 days since the start of the offensive. The fighting for Belyov proper began on the morning of December 27; it had been transformed into a powerful fortified defensive area equipped with a considerable amount of artillery, mortars and machine guns. It was considered an important covering position on the Oryol axis. During the latter half of December 28 the 239th and 324th Divisions advanced in fighting to the line Kudrino–Davydovo and continued to attack to the west. The next day the two divisions reached the Kozelsk area, where they linked up with the 1st Guards Cavalry. Meanwhile, the 322nd and 330th Divisions enveloped the German Belyov grouping along several axes, forcing it to withdraw into the town with heavy casualties; The dogged fighting continued all through December 30, and finally concluded around 1300 hours on December 31 when it was finally liberated. Large quantities of equipment were captured and the survivors withdrew to the west and southwest.[13]

Drive on Yukhnov

During the first 10 days of January 1942, the left-wing armies of Western Front, including the 10th, also recaptured Meshchovsk, Lyudinovo, and Kirov. By January 1 the 239th was making a fighting approach to the line Khoten–Klesovo, trying to outflank Sukhinichi from the north. The next day it joined the 324th in the fighting for that place, but the initial frontal attack ended unsuccessfully, as did the succeeding efforts that continued until January 5. Golikov then decided to maintain the offensive by blocking Sukhinichi, primarily with the 324th, but also with two companies of the 239th. The remainder of the division was directed against Meshchovsk, which was soon freed. From this time the left wing armies of Western Front focused on the attempt to reach the Minsk–Warsaw highway and the Vyazma–Bryansk lateral railroad. The key to breaking the highway was the city of Yukhnov, but the main forces of 10th Army were directed to the area of Kirov and Lyudinovo against the railroad. In the afternoon of January 7 the 239th occupied Serpeysk and continued its attack to the northwest. The 1st Guards Cavalry Corps, which had failed to take Yukhnov earlier, turned toward Mosalsk on January 8, which it was to capture in conjunction with 10th Army. It accomplished this overnight on January 8/9, assisted by the 325th Division. By January 12 the 239th was fighting in the area Kirsanova–Pyatnitsa–Shershnevo–Krasnyi Kholm and attacking in the direction of Chiplyaevo station. On January 16 the division was directly subordinated to the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps, as had been the 325th earlier.[14]

In mid-January an operation was planned for 43rd Army to capture Myatlevo, in conjunction with 49th and 50th Armies and the 1st Guards Cavalry, in an effort to surround and destroy the German Kondrovo-Yukhnov grouping. The operation would also involve the employment of airborne troops, some of which had been dropped in the Myatlevo area as early as January 3. The 250th Airborne Regiment was to aid the 1st Guards Cavalry's offensive and to secure the advance of 33rd Army to the west. The first part of the landing took place on the pre-dawn of January 18, with more men following the next afternoon. Two battalions reached Petrishchevo on January 22 and on January 28 linked up with 1st Guards Cavalry in the Tynovka area. On January 30 the balance of the 250th Regiment came into contact with the Corps and on February 4 was subordinated to Colonel Martirosyan's command.[15]

Battles of Rzhev

The first Rzhev-Vyazma Offensive had begun on January 8 and eventually involved most of the armies of Western and Kalinin Fronts. The push on Yukhnov by 1st Guards Cavalry and 50th Army is considered part of the opening phase of this offensive, and the objective of the Corps was to form one prong of the encirclement of the German 4th and 9th Armies. Overnight on January 27/28 7,000 mounted men of five of the Corps' cavalry divisions slipped through a gap in the German lines and began a raid toward Vyazma, although its attached rifle divisions and most of its heavy equipment were forced to remain south of the Warsaw highway.[16] Under the circumstances the 239th returned to the command of 50th Army during February.[17]

As Army Group Center received reinforcements and its position began to stabilize, some of the counterattacking armies of the two Fronts became partially or entirely encircled. 33rd Army fell into such a position near Yukhnov and the 49th and 50th Armies were ordered to bring relief. Between February 17 and 23 additional airborne troops were dropped to link up with 50th Army in order to assist its attack in the direction of Vyazma, but this proved unsuccessful. However, Yukhnov was finally liberated on March 5. Soon the 43rd, 49th and 50th Armies were ordered to link up with the 33rd Army and 1st Guards Cavalry Corps by March 27. This effort failed, as did another attempt by the 50th on April 14 which got to within 2,000m of the Cavalry before being halted and turned back. The Cavalry group finally began an effort to break out in the direction of Yelnya on June 9 and reached the lines of 10th Army south of the Warsaw highway on June 23.[18] By this time the 239th had been shifted back to this Army.[19]

First Rzhev-Sychyovka Offensive

Prior to the start of the summer offensive against 9th Army the division had been again reassigned, now to 31st Army, still in Western Front.[20] Western Front began its part in the operation on August 4. A powerful artillery preparation reportedly knocked out 80 percent of German weapons, after which the German defenses were penetrated on both sides of Pogoreloe Gorodishche and the 31st Army's mobile group rushed through the breaches towards Zubtsov. By the evening of August 6 the breach in 9th Army's front had expanded up to 30km wide and up to 25km deep. The following day the STAVKA appointed Army Gen. G. K. Zhukov to coordinate the offensives of Western and Kalinin Fronts; Zhukov proposed to liberate Rzhev with 31st and 30th Armies as soon as August 9. However, heavy German counterattacks, complicated by adverse weather, soon slowed the advance drastically. On August 23 the 31st Army, in concert with elements of the 29th Army, finally liberated Zubtsov. While this date is officially considered the end of the offensive in Soviet sources, in fact bitter fighting continued west of Zubtsov into mid-September. At dawn on September 8, 29th and 31st Armies went on a determined offensive to seize the southern part of Rzhev. Despite resolute attacks through the following day against the German 161st Infantry Division the 31st made little progress. It suspended its attacks temporarily on September 16 but resumed them with three divisions on its right flank on September 21–23 with similar lack of success. Over the course of the fighting from August 4 to September 15 the Army suffered a total of 43,321 total losses in personnel.[21]

Operation Mars

On August 29 Colonel Martirosyan had been severely shell-shocked and had to be hospitalized. After he recovered he spent most of 1943 and 1944 in the training establishment and was promoted to the rank of major general on September 1, 1943. He returned to the front in November 1944 and briefly commanded the 90th Rifle Corps in 1945. His replacement in command of the 239th was Maj. Gen. Pyotr Nikolaevich Chernyshov, who had previously led the 11th Guards Rifle Division. In the planning for Operation Mars a directive was sent on September 28/29 from the command of Western Front to 31st Army, "consisting of the 88th, 239th, 336th and 20th Guards Rifle Divisions, the 32nd and 145th Tank Brigades... [to advance] along the Osuga, Artemovo, and Ligastaevo axis." The offensive finally began on November 25 when the Army's shock group, consisting of the above forces minus the 20th Guards, attacked the German 102nd Infantry Division. That division's history recorded:

At 7:30 a.m., the brown masses of Russian infantry emerged from their assembly places in the woods. Tanks, 25 thundering, spitting monsters, rolled forward to support them. Wave after wave of Russians advanced against the 102nd Infantry Division. The Germans were ready. Standing in their trenches they fired over their parapets into the enemy masses sweeping forward over the barren fields. Their machine-guns raked the Russians. Anti-tank guns cracked flatly; field guns roared. And the Russians fell. A handful reached the German lines and were captured. Others charged forward. But at 9:40 they paused to catch their breath. When they renewed their attacks, this time in a light snowfall, the men of the 102nd again drove them back. The end of the day found the Germans firmly in possession of their lines.[22]

In three days of fighting the tank brigades were decimated and the rifle divisions suffered heavy losses, up to 50 percent on the first day alone.[23] The Army then went over to the defense. On December 11 it went back to the attack, in support of 20th Army. These attacks continued until the 18th.[24] Soon after, what remained of the 239th left the front lines and began moving north, entering the reserves of Volkhov Front before the beginning of January 1943.[25]

Battles for Leningrad

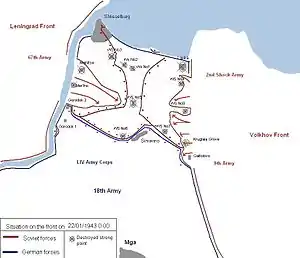

Volkhov and Leningrad Fronts began planning a new offensive to break the German blockade of that city in November 1942. As part of the preparations reinforcements were requested and the STAVKA complied in part by moving five rifle divisions, including the 239th, into Volkhov Front during December/January. The division was assigned to 2nd Shock Army, which formed the Front's shock group. It was intended to link up with the shock group of Leningrad Front, 67th Army, near Sinyavino and then protect the reconstruction of the rail line along the Ladoga Canal, restoring normal ground communications between the besieged city and the country as a whole. Although the two Fronts managed to complete their offensive preparations by January 1, on December 27 poor ice conditions on the Neva River forced a postponement to January 10-12. 2nd Shock was to smash the German defenses on a 12km-wide sector from Lipka to Gaitolovo, destroy the German forces in the eastern part of the salient in cooperation with 8th Army, and link up with 67th Army. For this task it had 11 rifle divisions, several brigades (including four of tanks), and a total of 37 artillery and mortar regiments.[26]

The offensive began on January 12 with a 140-minute artillery preparation on the 2nd Shock Army's front. All regimental and divisional artillery was mounted on skis or sleighs to improve mobility. The 239th was in the Army's second echelon. By the end of January 13 the Army had penetrated German defenses in two sectors along the 10km front between Lipka and Gaitolovo, one of which was 3km deep. As the advance slowed to a crawl the division, along with the 11th Rifle Division, the 12th and 13th Ski Brigades, and the 122nd Tank Brigade were all committed over the next three days. By January 17 the command of Army Group North understood the perilous situation its forces faced as the two Soviet Fronts were about to link up, as they did at 0930 hours on January 18, just east of Workers Settlement No. 1. At this point the joint force was ordered to wheel southward to capture Sinyavino and the Gorodok settlements. By this time the victorious forces were exhausted and the offensive was halted on January 31.[27] On January 21 General Chernyshov was removed from his command and placed at the disposal of Volkhov Front. He would later lead the 382nd and 17th Guards Rifle Divisions. He was replaced the following day by Col. Sergei Borisovich Kozachek, who had previously led the 2nd Cavalry Corps. On March 31 he would gain the rank of major general.

Mga Offensives

During February the division returned to direct command of Volkhov Front before joining 8th Army in March.[28] On March 19 this Army began a new assault toward Mga from its sector south of Voronovo after having been delayed:

The headquarters of the 8th Army... carefully planned the preparation and conduct of the operation under the chief of staff of the front... However, the forested swampy terrain spring conditions, the absence of roads, inadequate intelligence data about the enemy, especially concerning his system of fires in the depths of the first defensive belt, created definite difficulties in planning the employment of artillery, tanks and aviation. Greater difficulties were encountered with organizing supply of ammunition and other material and also with the creation of the required force grouping. All this led to the fact that the commencement of the offensive had to be delayed from 8 to 19 March.

The Army contained nine rifle divisions plus two rifle brigades, two tank brigades and four tank regiments, and the 239th was in second echelon; it faced the three infantry divisions of XXVI Army Corps. The assault began after a 135-minute artillery preparation and during the first three days of intense fighting the first echelon divisions penetrated 3-4km along a 7km front at the junction of the defending 1st and 223rd Infantry Divisions. The Army commander then committed a small mobile group with orders to cut the rail line between Mga and Kirishi, and then wheel northwest towards Mga Station. Despite heavy rain which prevented any air support, the group reached the rail line east of Turyshkino Station before being halted by hastily assembled German reinforcements. Despite the initial failure, Marshal Zhukov insisted the attacks continue through the rest of March, including the commitment of the second echelon formations, but further gains were marginal.[29]

The next month the 239th was shifted to 59th Army, still in Volkhov Front, but during June it went back to direct Front command before returning to 8th Army in the buildup to the Mga (5th Sinyavino) Offensive.[30] This began on July 22 with 8th Army attacking east of Mga, on an attack front of 13.6km and aiming to link up with 67th Army at or near Mga while detaching two rifle divisions and a tank brigade to strike at Sinyavino from the south. In order to penetrate the strong German defenses the Army commander, Lt. Gen. F. N. Starikov, organized his main forces into two shock groups. The 239th was in the second echelon of the northern shock group along with the 379th Rifle Division. The offensive was preceded by six days of artillery fire on the enemy positions, which were held by the 132nd Infantry Division. Despite the careful preparations the attack stalled after capturing the forward German trenches. Starikov made several efforts to renew the drive but was forced to call a halt on August 16, and his Army went over to the defense on August 22. By this time one soldier of the 132nd Infantry wrote that his division was "reduced by casualties and exhausted to the point of incoherence", but losses on the Soviet side were also heavy.[31]

Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive

By the end of the month the 239th was back in the reserves of Volkhov Front, but during September it returned to 59th Army where it joined the 6th Rifle Corps with the 256th and 310th Rifle Divisions.[32] Planning for the final offensive to drive Army Group North away from Leningrad began in November. The largest army and main strike force of Volkhov Front was the 59th, and the 6th and 14th Rifle Corps were tasked with penetrating the defenses of the XXXVIII Army Corps 50km north of Novgorod and sever German communications routes into that city from the west.[33] Prior to the offensive, on December 11 General Kozachek was moved to command of the 115th Rifle Corps, which he would lead for the duration of the war, being promoted to the rank of lieutenant general shortly after. Col. Aleksandr Yakovlevich Ordanovskii took over the 239th; he had been serving as commander of the 511th Rifle Regiment.

The assault began on January 14, 1944. The 6th Corps was in a bridgehead west of the Volkhov River on the Front's right flank. The 239th was in the Corps' first echelon along with the 310th, with the 65th Rifle Division in reserve, the 2nd Rifle Division of the 112th Rifle Corps in flank support, and the 16th Tank Brigade awaiting orders. In total the army fired 133,000 artillery rounds in preparation, and the ground assault went in at 1050 hours. However, 6th Corps stalled after just 1,000m, in large part due to poor use of the infantry support tanks. Just to the south, however, two regiments of the 378th Rifle Division of the 14th Corps staged a premature and unauthorized attack which tore through the first two German trench lines, easing the way for 6th Corps. The following day, the Corps' attack was reinforced with the 16th and 29th Tank Brigades, 65th Rifle Division, and a self-propelled artillery regiment. This was sufficient to secure an advance of 7km against heavy resistance, encircling and defeating elements of the German 28th Jäger Division. Later in the day the two tank brigades, along with the 239th, approached the Chudovo-Novgorod road and engaged a regiment of the 24th Infantry Division, forced it back, and cut a vital rail line. By late on January 16, the division had helped to tear a 20km wide hole in main German defense belt.[34] On January 21 the division would be recognized for its part in this victory with the Order of the Red Banner.[35]

Advance on Luga

On January 17, despite bad weather, difficult terrain and lack of transport, the 59th Army was clearly threatening to encircle the German XXXVIII Corps at Novgorod. On the night of January 19 these forces got the order to break out along the last remaining route. The city was liberated on the morning of the 20th, and on the next day most of the survivors of the German Corps were surrounded and soon destroyed by the 6th Corps and the 372nd Rifle Division. Following this success, 59th Army was directed to penetrate the second defensive belt, with 6th Corps attacking westward through Batetsky to Luga, supported on the right by 112th Corps. However, this advance quickly broke down as Army Group North reinforced the junction between its 16th and 18th Armies with an assortment of combat groups drawn from other sectors. On January 24 the 6th Corps' advance, still supported by 29th Tanks, faltered after only minimal gains. After-action reports stated that the Corps was exhausted and woefully understrength from its earlier fighting, and the 29th had only eight operational tanks. The advance turned into a slugfest in difficult terrain as the troops waded forward in waist-deep water, with artillery and tanks lagging far behind. The Corps made little progress in four days of fighting along the Batetsky-Luga railroad. By late on January 26 it had finally penetrated the second defensive line and reached the Luga River, but only by committing its second echelon.[36]

When the advance resumed the next day the 6th Corps seized a small bridgehead over the Luga but then utterly stalled east of Batetsky. On February 2 Volkhov Front resumed the offensive following the arrival of reinforcements. 59th Army was ordered to advance on Luga via Oredezh and Batetsky. It resumed its offensive westward but accomplished very little until February 8 due to heavy resistance from the remnants of XXXVIII Corps. Once 54th Army captured Orodezh on the same date the German withdrawal began in earnest. 6th Corps pursued but was again held up until February 12 by strong German defenses at Batetsky Station, while Luga was liberated by other forces.[37] Volkhov Front was disbanded on February 13, and the division was reassigned to the Leningrad Front, first in the 67th Army, where it was reassigned to 7th Rifle Corps.[38]

To the Panther Line

The next objectives for the southern forces of the Front were the cities of Pskov and Ostrov:

The main forces of the front's left wing, consisting of three armies (nine rifle corps), will be directed to capture the Ostrov region by enveloping Pskov from the north and forcing the Velikaia River. After which it will develop an offensive in the general direction of Riga.

The offensive was resumed on February 16. The remnants of XXVIII Army Corps stubbornly defended the approaches to the railroad south of Plyussa for three days against 67th Army's forces as part of its withdrawal to Pskov. The Army was now ordered to capture the German strongpoint at Strugi Krasnye on February 24 prior to breaching the central part of the Pskov-Ostrov fortified zone (Panther Line) in March. After taking Strugi Krasnye the Army resumed its pursuit, covering 65-90km from February 23-29. Near the end of this period the 7th and 110th Rifle Corps forced the Cherekha River from the march and then cut the Pskov-Opochka rail line. After reaching the Panther Line the 67th began making preparations to penetrate it, but by this point, after 45 days of almost continuous combat, most of its rifle divisions had decreased in strength to 2,500 - 3,500 personnel each. Efforts to breach the line continued until April 18 with scant results and at considerable cost in casualties.[39] During March the 7th Corps was transferred to 54th Army but in April the 239th left that Corps and returned to 67th Army (now in 3rd Baltic Front), where it was assigned to the 123rd Rifle Corps.[40]

Baltic Offensives

During June the division was moved to the 14th Rifle Corps which was in the reserves of the 1st Baltic Front.[41] The main Soviet summer offensive, Operation Bagration, had created an extensive gap between Army Groups Center and North and this Corps, temporarily assigned to 6th Guards Army, was in the vicinity of Sharkovshchina in the second week of July.[42] Later in the month the Corps was shifted to 4th Shock Army in 2nd Baltic Front, but the Army was moved to 1st Baltic a few weeks later.[43] Colonel Ordanovskii was wounded and hospitalized on July 26; after he recovered in November he went on to lead the 85th and 173rd Rifle Divisions but was killed in East Prussia in March 1945. He was replaced in command of the 239th by Maj. Gen. Konstantin Vladimirovich Vvedenskii, who had previously commanded the 85th Division.

By the beginning of August the division had advanced into Latvia and was located in the area of Ilūkste. As the advance continued into mid-September it reached the Biržai region in northern Lithuania.[44] General Vvedenskii had left the division on September 2 to take command of the 33rd Guards Rifle Division; he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Vladimir Stepanovich Potapenko, who had previously led the 279th Rifle Division and would remain in command of the 239th for the duration of the war. In the first week of October the forces of 14th Corps were near Žagarė as 4th Shock Army moved westward toward Memel.[45] On October 22 the 511th and 813th Rifle Regiments were both awarded the Order of Alexander Nevsky for their roles in breaking through the German defenses southwest of Riga.[46] By about this time the 688th Artillery Regiment was reduced to just three guns or howitzers per battery instead of four, and a total of just 64 men in each battery.[47]

Silesian Campaign

During December the division was moved to the 83rd Rifle Corps, still in 4th Shock Army in 1st Baltic Front, but in January 1945 it was again reassigned, now to the 42nd Army in 2nd Baltic Front, where it was under direct Army command.[48] This Army was part of the force containing the German units trapped in the Courland Pocket, but as this was increasingly a backwater the division could be more profitably employed elsewhere. On February 7 it entered the Reserve of the Supreme High Command for rebuilding and redeployment; this ended on February 28 when it joined the 93rd Rifle Corps in 1st Ukrainian Front,[49] which was currently operating in Silesia. The 239th would remain under these commands for the duration of the war. The Corps also contained the 98th and 391st Rifle Divisions and was soon assigned to 59th Army, which was in the Ratibor area.[50]

On February 24, immediately following the Lower Silesian Offensive, the Front commander, Marshal I. S. Konev, presented his plan for subsequent operations. Upon the arrival of the Front's main group of forces in the Neisse area the 59th and 60th Armies were to develop the attack from the bridgehead north of Ratibor to the west and southwest. Ultimately this operation would encircle and destroy the German group of forces in the Oppeln salient. 59th Army would launch its main attack along the left flank with the 93rd and 115th Rifle Corps and the 7th Guards Mechanized Corps in the general direction of Kostenthal and Zultz. 93rd Corps would have just the 98th Division in the first echelon. The 391st would be committed on the second day while the main forces of the 239th, less one rifle regiment in Army reserve, comprised the third echelon to develop the offensive's success.[51]

The offensive on the 59th and 60th Army's sector began at 0850 hours on March 15 following an 80-minute artillery preparation and went largely according to plan although more slowly than expected. The main German defense zone was broken through on a 12km front and the Armies advanced 6-8km during the day. Bad weather prevented air support before noon, and the advancing forces also had to repel ten counterattacks. In response Konev ordered that the advance continue through the night. During the day on March 16 the 59th Army managed to advance another 3-9km, and the 93rd Corps and 7th Guards Mechanized Corps cleared the entire depth of the German defenses and set the stage for the success of the attack over the next two days. By the end of March 17 the two corps had reached the line Tomas–Schenau–Kittledorf while the 115th Corps covered against flank attacks from the north. By noon on the next day the 93rd and 7th Guards forced the Hotzenplotz River and began to pursue the remnants of the defeated German forces. During the day the 59th Army linked up with the 21st Army, encircling the 20th SS, 168th and 344th Infantry Divisions, part of the 18th SS Panzergrenadier Division, and several independent regiments and battalions in the area southwest of Oppeln.[52]

With the encirclement completed the 93rd Corps was tasked with preventing the encircled grouping from breaking out to the southwest. The 239th was located along the line Glesen–Pommerswitz–Steubendorf, ready to repel possible German attempts to break out of the encirclement or any relief attempts from outside. On March 19 an attack against several units the Corps was quickly recognized as a feint to disguise the actual direction of the planned breakout, which was in the 21st Army's sector. All these efforts were beaten back, as was a break-in attempt by the Hermann Göring Panzer Division towards Steinau. At the same time the remaining encircling forces attacked into the pocket to break up and liquidate the defenders. By March 20 this task was largely completed, with total German casualties of 30,000 killed, 15,000 prisoners, 21 aircraft, 57 tanks and assault guns and 464 guns of various calibers. On March 21 the 59th Army resumed its advance in the direction of Jägerndorf which it reached but did not take on March 31. Due to the toll of casualties during the offensive and inadequate supplies of ammunition, the Army was ordered to go over to the defense.[53] During this advance the town of Leobschütz was taken on March 24 and on April 26 the 511th Rifle Regiment would be awarded the Order of Kutuzov, 3rd Degree, for its part in this victory.[54]

Postwar

Beginning on May 6 the division advanced with its Corps and Army in the Prague offensive, and took part in the final encirclement of Army Group Center. When the fighting ended its personnel shared the full title 239th Rifle, Order of the Red Banner Division. (Russian: 239-я стрелковая Краснознамённая дивизия.) According to STAVKA Order No. 11096 of May 29, 1945, part 8, the 239th is listed as one of the rifle divisions to be "disbanded in place".[55] It was disbanded in accordance with the directive in July 1945.

References

Citations

- Charles C. Sharp, "The Deadly Beginning", Soviet Tank, Mechanized, Motorized Divisions and Tank Brigades of 1940 - 1942, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. I, Nafziger, 1995, p. 67. Grylev (see Bibliography) has no order of battle for the 239th Motorized.

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 13

- Walter S. Dunn, Jr., Stalin's Keys to Victory, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2007, p. 77

- Sharp, "The Deadly Beginning", p. 67

- Sharp, "Red Tide", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed From June to December 1941, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, vol. IX, Nafziger, 1996, p. 39

- Sharp, "Red Tide", p. 39

- David M. Glantz, Before Stalingrad, Tempus Publishing Ltd., Stroud, UK, 2003, pp. 161, 255-56

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd. Solihull, UK, 2015, Kindle ed., Part III, ch. 5

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 75

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part III, ch. 2; Part IV, ch. 4

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part IV, ch. 4

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part IV, ch. 4

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part IV, ch. 4; Part V, chs. 1, 5

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part V, chs. 5, 8

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part V, ch. 9

- Svetlana Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, ed. & trans S. Britton, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2013, pp. 26-27, 32

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 45

- Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, pp. 41, 43, 45, 48, 58

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 102

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 145

- Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, pp. 74, 82-83, 85-87, 94-95, 99

- Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999, p. 82

- Glantz, After Stalingrad, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2011, pp. 43, 475

- Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, pp. 111-12, 117

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 10

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2002, pp. 264-67

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 269, 274-75, 280, 282-84

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 58, 81

- Glantz, After Stalingrad, pp. 438-39

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 105, 157, 185

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 306-09, 311-14

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 214, 244

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 333, 335

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 345-47

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 257.

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 347-49, 360-61

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 362-63, 384-85, 388

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 66

- Glantz, The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944, pp. 388-89, 392-94, 396, 405, 408

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 96, 127

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 189

- The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, Multi-Man Publishing, Inc., Millersville, MD, 2009, p. 14

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 217, 250

- The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, pp. 22, 29

- The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, p. 35

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 519.

- Sharp, "Red Tide", p. 39

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, pp. 9, 41

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, p. 90

- Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, pp. 471, 477

- Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 469, 477-78

- Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 503-04, 506-09

- Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 510-14, 519-20

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 159.

- STAVKA Order No. 11096

Bibliography

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967a). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть I. 1920 - 1944 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part I. 1920–1944] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967b). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть II. 1945 – 1966 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part II. 1945–1966] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. p. 109

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. pp. 221-22

External links

- Gayk Oganesovich Martirosyan

- Pyotr Nikolaevich Chernyshov

- Sergei Borisovich Kozachek

- Konstantin Vladimirovich Vvedenskii

- Vladimir Stepanovich Potapenko