Battle of Moscow

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a 600 km (370 mi) sector of the Eastern Front during World War II, between September 1941 and January 1942. The Soviet defensive effort frustrated Hitler's attack on Moscow, the capital and largest city of the Soviet Union. Moscow was one of the primary military and political objectives for Axis forces in their invasion of the Soviet Union.

| Battle of Moscow | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

Soviet anti-aircraft gunners on the roof of the Hotel Moskva | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| As of 1 October 1941: | As of 1 October 1941: | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

German strategic offensive: (1 October 1941 to 10 January 1942)

German estimated: 174,194 KIA, WIA, MIA (see §7)[14] Soviet estimated: 581,000 killed, missing, wounded and captured.[15] |

Moscow Defense:[16] (30 September 1941 to 5 December 1941)

| ||||||

The German Strategic Offensive, named Operation Typhoon, called for two pincer offensives, one to the north of Moscow against the Kalinin Front by the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies, simultaneously severing the Moscow–Leningrad railway, and another to the south of Moscow Oblast against the Western Front south of Tula, by the 2nd Panzer Army, while the 4th Army advanced directly towards Moscow from the west.

Initially, the Soviet forces conducted a strategic defence of the Moscow Oblast by constructing three defensive belts, deploying newly raised reserve armies, and bringing troops from the Siberian and Far Eastern Military Districts. As the German offensives were halted, a Soviet strategic counter-offensive and smaller-scale offensive operations forced the German armies back to the positions around the cities of Oryol, Vyazma and Vitebsk, and nearly surrounded three German armies. It was a major setback for the Germans, and the end of their belief in a swift German victory over the USSR.[17] As a result of the failed offensive, Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch was dismissed as supreme commander of the German Army, with Hitler replacing him in the position.

Background

Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion plan, called for the capture of Moscow within four months. On 22 June 1941, Axis forces invaded the Soviet Union, destroyed most of the Soviet Air Force on the ground, and advanced deep into Soviet territory using blitzkrieg tactics to destroy entire Soviet armies. The German Army Group North moved towards Leningrad, Army Group South took control of Ukraine, and Army Group Centre advanced towards Moscow. By July 1941, Army Group Centre crossed the Dnieper River, on the path to Moscow.[18]

On 15 July 1941, German forces captured Smolensk, an important stronghold on the road to Moscow.[19] At this stage, although Moscow was vulnerable, an offensive against the city would have exposed the German flanks. In part to address these risks, and to attempt to secure Ukraine's food and mineral resources, Hitler ordered the attack to turn north and south to eliminate Soviet forces at Leningrad and Kiev.[20] This delayed the German advance on Moscow.[20] When that advance resumed on 30 September 1941, German forces had been weakened, while the Soviets had raised new forces for the defence of the city.[20]

Initial German advance (30 September – 10 October)

Plans

For Hitler, the Soviet capital was secondary, and he believed the only way to bring the Soviet Union to its knees was to defeat it economically. He felt this could be accomplished by seizing the economic resources of Ukraine east of Kiev.[21] When Walther von Brauchitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the Army, supported a direct thrust to Moscow, he was told that "only ossified brains could think of such an idea".[21] Franz Halder, head of the Army General Staff, was also convinced that a drive to seize Moscow would be victorious after the German Army inflicted enough damage on the Soviet forces.[22] This view was shared by most within the German high command.[21] But Hitler overruled his generals in favor of pocketing the Soviet forces around Kiev in the south, followed by the seizure of Ukraine. The move was successful, resulting in the loss of nearly 700,000 Red Army personnel killed, captured, or wounded by 26 September, and further advances by Axis forces.[23]

With the end of summer, Hitler redirected his attention to Moscow and assigned Army Group Centre to this task. The forces committed to Operation Typhoon included three infantry armies (the 2nd, 4th, and 9th)[24] supported by three Panzer (tank) Groups (the 2nd, 3rd and 4th) and by the Luftwaffe's Luftflotte 2. Up to two million German troops were committed to the operation, along with 1,000–2,470 tanks and assault guns and 14,000 guns. German aerial strength, however, had been severely reduced over the summer's campaign; the Luftwaffe had lost 1,603 aircraft and 1,028 had been damaged. Luftflotte 2 had only 549 serviceable machines, including 158 medium and dive-bombers and 172 fighters, available for Operation Typhoon.[25] The attack relied on standard blitzkrieg tactics, using Panzer groups rushing deep into Soviet formations and executing double-pincer movements, pocketing Red Army divisions and destroying them.[26]

Facing the Wehrmacht were three Soviet fronts forming a defensive line based on the cities of Vyazma and Bryansk, which barred the way to Moscow. The armies comprising these fronts had also been involved in heavy fighting. Still, it was a formidable concentration consisting of 1,250,000 men, 1,000 tanks and 7,600 guns. The Soviet Air Force (VVS) had suffered appalling losses of some 7,500 to 21,200 aircraft.[27][28] Extraordinary industrial achievements had begun to replace these, and at the outset of Typhoon the VVS could muster 936 aircraft, 578 of which were bombers.[29]

Once Soviet resistance along the Vyazma-Bryansk front was eliminated, German forces were to press east, encircling Moscow by outflanking it from the north and south. Continuous fighting had reduced their effectiveness, and logistical difficulties became more acute. General Heinz Guderian, commander of the 2nd Panzer Army, wrote that some of his destroyed tanks had not been replaced, and there were fuel shortages at the start of the operation.[30]

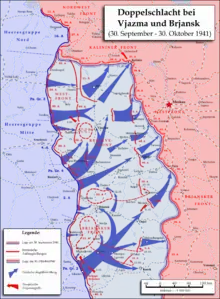

Battles of Vyazma and Bryansk

The German attack went according to plan, with 4th Panzer Group pushing through the middle nearly unopposed and then dividing its mobile forces north to complete the encirclement of Vyazma with 3rd Panzer Group, and other units south to close the ring around Bryansk in conjunction with 2nd Panzer Group. The Soviet defenses, still under construction, were overrun, and spearheads of the 3rd and 4th Panzer Groups met at Vyazma on 10 October 1941.[31][32] Four Soviet armies (the 16th, 19th, 20th, 24th and part of the 32nd) were encircled in a large pocket just west of the city.[33]

The encircled Soviet forces continued to fight, and the Wehrmacht had to employ 28 divisions to eliminate them, using troops which could have supported the offensive towards Moscow. The remnants of the Soviet Western and Reserve Fronts retreated and manned new defensive lines around Mozhaisk.[33] Although losses were high, some of the encircled units escaped in small groups, ranging in size from platoons to full rifle divisions.[32] Soviet resistance near Vyazma also provided time for the Soviet high command to reinforce the four armies defending Moscow (the 5th, 16th, 43rd and 49th Armies). Three rifle and two tank divisions were transferred from East Siberia with more to follow.[33]

The weather began to change, hampering both sides. On 7 October, the first snow fell and quickly melted, turning roads and open areas into muddy quagmires, a phenomenon known as rasputitsa in Russia. German armored groups were greatly slowed, allowing Soviet forces to fall back and regroup.[34][35]

Soviet forces were able to counterattack in some cases. For example, the 4th Panzer Division fell into an ambush set by Dmitri Leliushenko's hastily formed 1st Guards Special Rifle Corps, including Mikhail Katukov's 4th Tank Brigade, near the city of Mtsensk. Newly built T-34 tanks were concealed in the woods as German armor rolled past them; as a scratch team of Soviet infantry contained their advance, Soviet armor attacked from both flanks and savaged the German Panzer IV tanks. For the Wehrmacht, the shock of this defeat was so great that a special investigation was ordered.[32] Guderian and his troops discovered, to their dismay, that the Soviet T-34s were almost impervious to German tank guns. As the general wrote, "Our Panzer IV tanks with their short 75 mm guns could only explode a T-34 by hitting the engine from behind". Guderian also noted in his memoirs that "the Russians already learned a few things".[36][37] In 2012, Niklas Zetterling disputed the notion of a major German reversal at Mtsensk, noting that only a battlegroup from the 4th Panzer Division was engaged while most of the division was fighting elsewhere, that both sides withdrew from the battlefield after the fighting and that the Germans lost only six tanks destroyed and three damaged. For German commanders like Hoepner and Bock, the action was inconsequential; their primary worry was resistance from within the pocket, not outside it.[38]

.jpg.webp)

Other counterattacks further slowed the German offensive. The 2nd Army, which was operating to the north of Guderian's forces with the aim of encircling the Bryansk Front, had come under strong Red Army pressure assisted by air support.[39]

According to German assessments of the initial Soviet defeat, 673,000 soldiers had been captured by the Wehrmacht in both the Vyazma and Bryansk pockets,[40] although recent research suggests a lower—but still enormous—figure of 514,000 prisoners, reducing Soviet strength by 41%.[41] Personnel losses of 499,001 (permanent as well as temporary) were calculated by the Soviet command.[42] On 9 October, Otto Dietrich of the German Ministry of Propaganda, quoting Hitler himself, forecast in a press conference the imminent destruction of the armies defending Moscow. As Hitler had never had to lie about a specific and verifiable military fact, Dietrich convinced foreign correspondents that the collapse of all Soviet resistance was perhaps hours away. German civilian morale—low since the start of Barbarossa—significantly improved, with rumors of soldiers home by Christmas and great riches from the future Lebensraum in the east.[43]

However, Red Army resistance had slowed the Wehrmacht. When the Germans arrived within sight of the Mozhaisk line west of Moscow on 10 October, they encountered another defensive barrier manned by new Soviet forces. That same day, Georgy Zhukov, who had been recalled from the Leningrad Front on 6 October, took charge of Moscow's defense and the combined Western and Reserve Fronts, with Colonel General Ivan Konev as his deputy.[44][45] On 12 October, Zhukov ordered the concentration of all available forces on a strengthened Mozhaisk line, a move supported by General Vasilevsky of the General Staff.[46] The Luftwaffe still controlled the sky wherever it appeared, and Stuka and bomber groups flew 537 sorties, destroying some 440 vehicles and 150 artillery pieces.[47][48]

On 15 October, Stalin ordered the evacuation of the Communist Party, the General Staff and various civil government offices from Moscow to Kuibyshev (now Samara), leaving only a limited number of officials behind. The evacuation caused panic among Muscovites. On 16–17 October, much of the civilian population tried to flee, mobbing the available trains and jamming the roads from the city. Despite all this, Stalin publicly remained in the Soviet capital, somewhat calming the fear and pandemonium.[32]

Mozhaisk defense line (13–30 October)

By 13 October 1941, the Wehrmacht had reached the Mozhaisk defense line, a hastily constructed set of four lines of fortifications[24] protecting Moscow's western approaches which extended from Kalinin towards Volokolamsk and Kaluga. Despite recent reinforcements, only around 90,000 Soviet soldiers manned this line—far too few to stem the German advance.[49][50] Given the limited resources available, Zhukov decided to concentrate his forces at four critical points: the 16th Army under Lieutenant General Konstantin Rokossovsky guarded Volokolamsk, Mozhaisk was defended by 5th Army under Major General Leonid Govorov, the 43rd Army of Major General Konstantin Golubev defended Maloyaroslavets, and the 49th Army under Lieutenant General Ivan Zakharkin protected Kaluga.[51] The entire Soviet Western Front—nearly destroyed after its encirclement near Vyazma—was being recreated almost from scratch.[52]

.jpg.webp)

Moscow itself was also hastily fortified. According to Zhukov, 250,000 women and teenagers worked building trenches and anti-tank moats around Moscow, moving almost three million cubic meters of earth with no mechanical help. Moscow's factories were hastily converted to military tasks: one automobile factory was turned into a submachine gun armory, a clock factory manufactured mine detonators, the chocolate factory shifted to food production for the front, and automobile repair stations worked fixing damaged tanks and military vehicles.[53] Despite these preparations, the capital was within striking distance of German tanks, with the Luftwaffe mounting large-scale air raids on the city. The air raids caused only limited damage because of extensive anti-aircraft defenses and effective civilian fire brigades.[54]

On 13 October 1941 (15 October, according to other sources), the Wehrmacht resumed its offensive. At first, the German forces attempted to bypass Soviet defenses by pushing northeast towards the weakly protected city of Kalinin and south towards Kaluga and Tula, capturing all except Tula by 14 October. Encouraged by these initial successes, the Germans launched a frontal assault against the fortified line, taking Mozhaisk and Maloyaroslavets on 18 October, Naro-Fominsk on 21 October, and Volokolamsk on 27 October after intense fighting. Because of the increasing danger of flanking attacks, Zhukov was forced to fall back,[32] withdrawing his forces east of the Nara river.[55]

In the south, the Second Panzer Army initially advanced towards Tula with relative ease because the Mozhaisk defense line did not extend that far south and no significant concentrations of Soviet troops blocked their advance. However, bad weather, fuel problems, and damaged roads and bridges eventually slowed the German army, and Guderian did not reach the outskirts of Tula until 26 October.[56] The German plan initially called for the rapid capture of Tula, followed by a pincer move around Moscow. The first attack, however, was repelled by the 50th Army and civilian volunteers on 29 October, after a fight within sight of the city. This was followed by the counter-offensive by the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps whose flanks were secured by the 10th Army, 49th Army and 50th Army who attacked from Tula.[57] On 31 October, the German Army high command ordered a halt to all offensive operations until increasingly severe logistical problems were resolved and the rasputitsa subsided.

Wehrmacht advance towards Moscow (1 November – 5 December)

Wearing down

By late October, the German forces were worn out, with only a third of their motor vehicles still functioning, infantry divisions at third- to half-strength, and serious logistics issues preventing the delivery of warm clothing and other winter equipment to the front. Even Hitler seemed to surrender to the idea of a long struggle, since the prospect of sending tanks into such a large city without heavy infantry support seemed risky after the costly capture of Warsaw in 1939.[58]

To stiffen the resolve of the Red Army and boost civilian morale, Stalin ordered the traditional military parade on 7 November (Revolution Day) to be staged in Red Square. Soviet troops paraded past the Kremlin and then marched directly to the front. The parade carried a great symbolic significance by demonstrating the continued Soviet resolve, and was frequently invoked as such in the years to come. Despite this brave show, the Red Army's position remained precarious. Although 100,000 additional Soviet soldiers had reinforced Klin and Tula, where renewed German offensives were expected, Soviet defenses remained relatively thin. Nevertheless, Stalin ordered several preemptive counteroffensives against German lines. These were launched despite protests from Zhukov, who pointed out the complete lack of reserves.[59] The Wehrmacht repelled most of these counteroffensives, which squandered Soviet forces that could have been used for Moscow's defense. The only notable success of the offensive occurred west of Moscow near Aleksino, where Soviet tanks inflicted heavy losses on the 4th Army because the Germans still lacked anti-tank weapons capable of damaging the new, well-armoured T-34 tanks.[58]

From 31 October to 13–15 November, the Wehrmacht high command stood down while preparing to launch a second offensive towards Moscow. Although Army Group Centre still possessed considerable nominal strength, its fighting capabilities had been vitiated by wear and fatigue. While the Germans were aware of the continuous influx of Soviet reinforcements from the east as well as the presence of large reserves, given the tremendous Soviet casualties, they did not expect the Soviets to be able to mount a determined defense.[60] But in comparison to the situation in October, Soviet rifle divisions occupied a much stronger defensive position: a triple defensive ring surrounding the city and some remnants of the Mozhaisk line near Klin. Most of the Soviet field armies now had a multilayered defense, with at least two rifle divisions in second echelon positions. Artillery support and sapper teams were also concentrated along major roads that German troops were expected to use in their attacks. There were also many Soviet troops still available in reserve armies behind the front. Finally, Soviet troops—and especially officers—were now more experienced and better prepared for the offensive.[58]

By 15 November 1941, the ground had finally frozen, solving the mud problem. The armored Wehrmacht spearheads, consisting of 51 divisions, could now advance, with the goal of encircling Moscow and linking up near the city of Noginsk, east of the capital. To achieve this objective, the German Third and Fourth Panzer Groups needed to concentrate their forces between the Volga Reservoir and Mozhaysk, then proceed past the Soviet 30th Army to Klin and Solnechnogorsk, encircling the capital from the north. In the south, the Second Panzer Army intended to bypass Tula, still held by the Red Army, and advance to Kashira and Kolomna, linking up with the northern pincer at Noginsk. The German 4th Field Army in the centre were to "pin down the troops of the Western Front."[45]: 33, 42–43

Failed pincer

On 15 November 1941, German tank armies began their offensive towards Klin, where no Soviet reserves were available because of Stalin's wish to attempt a counteroffensive at Volokolamsk, which had forced the relocation of all available reserve forces further south. Initial German attacks split the front in two, separating the 16th Army from the 30th.[58] Several days of intense combat followed. Zhukov recalled in his memoirs that "The enemy, ignoring the casualties, was making frontal assaults, willing to get to Moscow by any means necessary".[61] Despite the Wehrmacht's efforts, the multi-layered defense reduced Soviet casualties as the Soviet 16th Army slowly retreated and constantly harassed the German divisions which were trying to make their way through the fortifications.

The Third Panzer Army captured Klin after heavy fighting on 23 November, Solnechnogorsk as well by 24 November and Istra, by 24/25 November. Soviet resistance was still strong, and the outcome of the battle was by no means certain. Reportedly, Stalin asked Zhukov whether Moscow could be successfully defended and ordered him to "speak honestly, like a communist". Zhukov replied that it was possible, but reserves were urgently needed.[61] By 27 November, the German 7th Panzer Division had seized a bridgehead across the Moscow-Volga Canal—the last major obstacle before Moscow—and stood less than 35 km (22 mi) from the Kremlin;[58] but a powerful counterattack by the 1st Shock Army drove them back.[62] Just northwest of Moscow, the Wehrmacht reached Krasnaya Polyana, little more than 29 km (18 mi) from the Kremlin in central Moscow;[63] German officers were able to make out some of the major buildings of the Soviet capital through their field glasses. Both Soviet and German forces were severely depleted, sometimes having only 150–200 riflemen—a company's full strength—left in a regiment.[58]

.jpg.webp)

In the south, near Tula, combat resumed on 18 November 1941, with the Second Panzer Army trying to encircle the city.[58] The German forces involved were extremely battered from previous fighting and still had no winter clothing. As a result, initial German progress was only 5–10 km (3.1–6.2 mi) per day.[64] Moreover, it exposed the German tank armies to flanking attacks from the Soviet 49th and 50th Armies, located near Tula, further slowing the advance. Guderian nevertheless was able to pursue the offensive, spreading his forces in a star-like attack, taking Stalinogorsk on 22 November 1941 and surrounding a Soviet rifle division stationed there.

On 26 November 1941, the German 2nd Panzer Army under General Heinz Guderian began advancing towards Kashira, which was a strategic stronghold that lay 120 kilometres southwest of Moscow and 80 kilometres northeast of Tula. Kashira was of paramount importance, considering that it was the headquarters of the Soviet Western Front, one of the three main groups of resistance against the Nazi storm. The Germans were capable of seizing Venev and pushing towards storming formidably towards Kashira. Should Kashira fall, the road to Moscow would be open for the 2nd Panzer Group. In an attempt to halt the onslaught of the 2nd Panzer Group, the STAVKA High Command hurled Major General Pavel Belov's 1st Guards Cavalry Corps, General Andrei Getman's 112th Tank Division, an armoured brigade and a battalion of BM-13 Katyusha rocket launchers along with support from the air force against the armoured beast of the Wehrmacht. The cavalrymen of the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps, which was primarily armed with the SVT-41 semi-automatic battle rifle and Cossack shashkas, as well as the mechanized troops possessing T34 M1940 and KV-1 tanks, battled relentlessly against Heinz Guderian's 2nd Panzer Group. After much vicious fighting, the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps was able to repel the armoured forces of Guderian and subsequently drove them back by 40 kilometres to the town of Mordves.[65]

The Germans were driven back in early December, securing the southern approach to the city.[66] Tula itself held, protected by fortifications and determined defenders mostly from the 50th Army, made of both soldiers and civilians. In the south, the Wehrmacht never got close to the capital. The first stroke of the Western-Front's counter-offensive on the outskirts of Moscow fell upon Guderian's 2nd Panzer Army.[67]

Because of the resistance on both the northern and southern sides of Moscow, on 1 December the Wehrmacht attempted a direct offensive from the west along the Minsk-Moscow highway near the city of Naro-Fominsk. This offensive had limited tank support and was directed against extensive Soviet defenses. After meeting determined resistance from the Soviet 1st Guards Motorized Rifle Division and flank counterattacks staged by the 33rd Army, the German offensive stalled and was driven back four days later in the ensuing Soviet counteroffensive.[58] On the same day, the French-manned 638th Infantry Regiment, the only foreign formation of the Wehrmacht that took part in the advance on Moscow, went into action near the village of Diutkovo.[68] On 2 December, a reconnaissance battalion came to the town of Khimki—some 30 km (19 mi) away from the Kremlin in central Moscow reaching its bridge over the Moscow-Volga Canal as well as its railway station. This marked the closest approach of German forces to Moscow.[69][70]

The European Winter of 1941–42 was the coldest of the twentieth century.[71] On 30 November, von Bock claimed in a report to Berlin that the temperature was −45 °C (−49 °F).[72] General Erhard Raus, commander of the 6th Panzer Division, kept track of the daily mean temperature in his war diary. It shows a suddenly much colder period during 4–7 December: from −36 to −38 °C (−37 to −38 °F), although the method or reliability of his measurements is not known.[73] Other temperature reports varied widely.[74][75] Zhukov said that November's freezing weather stayed only around −7 to −10 °C (+19 to +14 °F).[76] Official Soviet Meteorological Service records show that at the lowest point, the lowest December temperature reached −28.8 °C (−20 °F).[76] These numbers indicated severely cold conditions, and German troops were freezing with no winter clothing, using equipment that was not designed for such low temperatures. More than 130,000 cases of frostbite were reported among German soldiers.[49] Frozen grease had to be removed from every loaded shell[49] and vehicles had to be heated for hours before use. The same cold weather hit the Soviet troops, but they were better prepared.[75] German clothing was supplemented by Soviet clothing and boots, which were often in better condition than German clothes as the owners had spent much less time at the front. Corpses were thawed out to remove the items; once when 200 bodies were left on the battlefield the "saw commandos" recovered sufficient clothing to outfit every man in a battalion.[77]

The Axis offensive on Moscow stopped. Heinz Guderian wrote in his journal that "the offensive on Moscow failed ... We underestimated the enemy's strength, as well as his size and climate. Fortunately, I stopped my troops on 5 December, otherwise the catastrophe would be unavoidable."[78]

Some historians have suggested that artificial floods played an important role in defending Moscow.[79] They were primarily meant to break the ice and prevent troops and heavy military equipment from crossing the Volga river and Ivankovo Reservoir.[80] This began with the blowing up of the Istra waterworks reservoir dam on 24 November 1941. On 28 November 1941, the water was drained into the Yakhroma and Sestra Rivers from six reservoirs (Khimki, Iksha, Pyalovskoye, Pestovskoye, Pirogovskoye, and Klyazma reservoirs), as well as from Ivankovo Reservoir using dams near Dubna.[79] This caused some 30–40 villages to become partially submerged even in the severe winter weather conditions of the time.[79][81] Both were results of Soviet General Headquarters' Order 0428 dated 17 November 1941. Artificial floods were also used as an unconventional weapon of direct impact.[82]

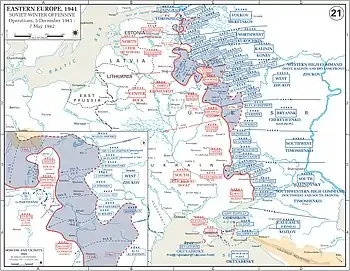

Soviet counter-offensive

Although the Wehrmacht's offensive had been stopped, German intelligence estimated that Soviet forces had no more reserves left and thus would be unable to stage a counteroffensive. This estimate proved wrong, as Stalin transferred over 18 divisions, 1,700 tanks, and over 1,500 aircraft from Siberia and the Far East after learning that Imperial Japan had no plans to invade the USSR in the near future from Richard Sorge.[83] The Red Army had accumulated a 58-division reserve by early December,[49] when the offensive proposed by Zhukov and Vasilevsky was finally approved by Stalin.[84] Even with these new reserves, Soviet forces committed to the operation numbered only 1,100,000 men,[74] only slightly outnumbering the Wehrmacht. Nevertheless, with careful troop deployment, a ratio of two-to-one was reached at some critical points.[49]

On 5 December 1941, the counteroffensive for "removing the immediate threat to Moscow" started on the Kalinin Front. The South-Western Front and Western Fronts began their offensives the next day. After several days of little progress, Soviet armies retook Solnechnogorsk on 12 December and Klin on 15 December. Guderian's army "beat a hasty retreat towards Venev" and then Sukhinichi. "The threat overhanging Tula was removed".[45]: 44–46, 48–51 [85]

On 8 December, Hitler had signed his directive No.39, ordering the Wehrmacht to assume a defensive stance on the whole front. German troops were unable to organize a solid defense at their initial locations and were forced to pull back to consolidate their lines. Guderian wrote that discussions with Hans Schmidt and Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen took place the same day, and both commanders agreed the current front line could not be held.[86] On 14 December, Franz Halder and Günther von Kluge finally gave permission for a limited withdrawal to the west of the Oka river, without Hitler's approval.[87][88] On 20 December, during a meeting with German senior officers, Hitler cancelled the withdrawal and ordered his soldiers to defend every patch of ground, "digging trenches with howitzer shells if needed".[89][90] Guderian protested, pointing out that losses from cold were actually greater than combat losses and that winter equipment was held by traffic ties in Poland.[91][92] Nevertheless, Hitler insisted on defending the existing lines, and Guderian was dismissed by 25 December, along with generals Hoepner and Strauss, commanders of the 4th Panzer and 9th Army, respectively. Fedor von Bock was also dismissed, officially for "medical reasons".[93] Walther von Brauchitsch, Hitler's commander-in-chief, had been removed even earlier, on 19 December.[45][94][95]

Meanwhile, the Soviet offensive continued in the north. The offensive liberated Kalinin and the Soviets reached Klin on 7 December, overrunning the headquarters of the LVI Panzer Corps outside the city. As the Kalinin Front drove west, a bulge developed around Klin. The Soviet front commander, General Ivan Konev, attempted to envelop any German forces remaining. Zhukov diverted more forces to the southern end of the bulge, to help Konev trap the Third Panzer Army. The Germans pulled their forces out in time. Although the encirclement failed, it unhinged the German defenses. A second attempt was made to outflank Army Group Centre's northern forces, but met strong opposition near Rzhev and was forced to halt, forming a salient that would last until March 1943. In the south, the offensive went equally well, with Southwestern Front forces relieving Tula on 16 December 1941. A major achievement was the encirclement and destruction of the German XXXV Corps, protecting Guderian's Second Panzer Army's southern flank.[96]

The Luftwaffe was paralysed in the second half of December. The weather, recorded as –42 °C (–44 °F), was a meteorological record.[97] Logistical difficulties and freezing temperatures created technical difficulties until January 1942. In the meantime, the Luftwaffe had virtually vanished from the skies over Moscow, while the Red Air Force, operating from better prepared bases and benefiting from interior lines, grew stronger.[97] On 4 January, the skies cleared. The Luftwaffe was quickly reinforced, as Hitler hoped it would save the situation. The Kampfgruppen (Bomber Groups) II./KG 4 and II./KG 30 arrived from refitting in Germany, whilst four Transportgruppen (Transport Groups) with a strength of 102 Junkers Ju 52 transports were deployed from Luftflotte 4 (Air Fleet 4) to evacuate surrounded army units and improve the supply line to the front-line forces. It was a last minute effort and it worked. The German air arm was to help prevent a total collapse of Army Group Centre. Despite the Soviets' best efforts, the Luftwaffe had contributed enormously to the survival of Army Group Centre. Between 17 and 22 December the Luftwaffe destroyed 299 motor vehicles and 23 tanks around Tula, hampering the Red Army's pursuit of the German Army.[98][99]

In the centre, Soviet progress was much slower. Soviet troops liberated Naro-Fominsk only on 26 December, Kaluga on 28 December, and Maloyaroslavets on 2 January, after ten days of violent action. Soviet reserves ran low, and the offensive halted on 7 January 1942, after having pushed the exhausted and freezing German armies back 100–250 km (62–155 mi) from Moscow. Stalin continued to order more offensives in order to trap and destroy Army Group Centre in front of Moscow, but the Red Army was exhausted and overstretched and they failed.[100]

Aftermath

Furious that his army had been unable to take Moscow, Hitler dismissed his commander-in-chief, Walther von Brauchitsch, on 19 December 1941, and took personal charge of the Wehrmacht,[94] effectively taking control of all military decisions. Hitler surrounded himself with staff officers with little or no recent combat experience.[101]

The Red Army's winter counter-offensive drove the Wehrmacht from Moscow, but the city was still considered to be threatened, with the front line relatively close. Because of this, the Moscow theater remained a priority for Stalin.[102] In particular, the initial Soviet advance was unable to reduce the Rzhev salient, held by several divisions of Army Group Centre. Immediately after the Moscow counter-offensive, a series of Soviet attacks (the Battles of Rzhev) were attempted against the salient, each time with heavy losses on both sides. By early 1943, the Wehrmacht had to disengage from the salient as the whole front was moving west. Nevertheless, the Moscow front was not finally secured until October 1943, when Army Group Centre was decisively repulsed from the Smolensk landbridge and from the left shore of the upper Dnieper at the end of the Second Battle of Smolensk.

For the first time since June 1941, Soviet forces had stopped the Germans and driven them back. This resulted in an overconfident Stalin further expanding the offensive. On 5 January 1942, during a meeting in the Kremlin, Stalin announced that he was planning a general spring offensive, which would be staged simultaneously near Moscow, Leningrad, Kharkov, and the Crimea. This plan was accepted over Zhukov's objections.[103] Low Red Army reserves and Wehrmacht tactical skill led to a bloody stalemate near Rzhev, known as the "Rzhev meat grinder", and to a string of Red Army defeats, such as the Second Battle of Kharkov, the failed attempt at elimination of the Demyansk pocket, and the encirclement of General Andrey Vlasov's army in a failed attempt to lift the siege of Leningrad, and the destruction of Red Army forces in Crimea. Ultimately, these failures would lead to a successful German offensive in the south and to the Battle of Stalingrad.

A documentary film, Moscow Strikes Back, (Russian: Разгром немецких войск под Москвой, "Rout of the German Troops near Moscow"), was made during the battle and rapidly released in the Soviet Union. It was taken to America and shown at the Globe in New York in August 1942. The New York Times reviewer commented that "The savagery of that retreat is a spectacle to stun the mind".[104] As well as the Moscow parade and battle scenes, the film included images of German atrocities committed during the occupation, "the naked and slaughtered children stretched out in ghastly rows, the youths dangling limply in the cold from gallows that were rickety, but strong enough".[104]

Legacy

The defense of Moscow became a symbol of Soviet resistance against the invading Axis forces. To commemorate the battle, Moscow was awarded the title of "Hero City" in 1965, on the 20th anniversary of Victory Day. A Museum of the Defence of Moscow was created in 1995.[105]

In the Russian capital of Moscow, an annual military parade on Red Square on 7 November was held in honor of the October Revolution Parade and as substitute for the October Revolution celebrations that haven't been celebrated on a national level since 1995. The parade is held to commemorate the historical event as a Day of Military Honour. The parade includes troops of the Moscow Garrison and the Western Military District, which usually numbers to close to 3,000 soldiers, cadets, and Red Army reenactors. The parade is presided by the Mayor of Moscow who delivers a speech during the event. Prior to the start of the parade, an historical reenactment of the Battle of Moscow is performed by young students, volunteers, and historical enthusiasts.[106]

The parade commands are always given by a high ranking veteran of the armed forces (usually with a billet of a Colonel) who gives the orders for the march past from the grandstand near the Lenin Mausoleum. On the command of Quick March! by the parade commander, the parade begins with the tune of Song of the Soviet Army, to which the historical color guards holding wartime symbols such as the Banner of Victory and the standards of the various military fronts march to. Musical support during the parade is always provided by the Massed Bands of the Moscow Garrison, which includes various military bands in the Western Military District, The Regimental Band of the 154th Preobrazhensky Regiment, and the Central Military Band of the Ministry of Defense of Russia.[107][108]

Casualties

Both German and Soviet casualties during the battle of Moscow have been a subject of debate, as various sources provide somewhat different estimates. Not all historians agree on what should be considered the "Battle of Moscow" in the timeline of World War II. While the start of the battle is usually regarded as the beginning of Operation Typhoon on 30 September 1941 (or sometimes on 2 October 1941), there are two different dates for the end of the offensive. In particular, some sources (such as Erickson[109] and Glantz[110]) exclude the Rzhev offensive from the scope of the battle, considering it as a distinct operation and making the Moscow offensive "stop" on 7 January 1942—thus lowering the number of casualties.

There are also significant differences in figures from various sources. John Erickson, in his Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies, gives a figure of 653,924 Soviet casualties between October 1941 and January 1942.[109] Glantz, in his book When Titans Clashed, gives a figure of 658,279 for the defense phase alone, plus 370,955 for the winter counteroffensive until 7 January 1942.[110] The official Wehrmacht daily casualty reports show 35,757 killed in action, 128,716 wounded, and 9,721 missing in action for the entire Army Group Centre between 1 October 1941 and 10 January 1942.[111] However, this official report does not match unofficial reports from individual battalion and divisional officers and commanders at the front, who record suffering far higher casualties than was officially reported.[112]

On the Russian side, discipline became ferocious. The NKVD blocking groups were ready to shoot anyone retreating without orders. NKVD squads went to field hospitals in search of soldiers with self-inflicted injuries, the so-called 'self shooters' – Those who shot themselves in the left hand to escape fighting. A surgeon in a field hospital of the Red Army admitted to amputating the hands of boys who tried this 'self-shooting' idea to escape fighting, to protect them from immediate execution via punishment squad.[113] In the first three months, blocking detachments shot 1,000 penal troops and sent 24,993 to penal battalions. By October 1942, the idea of regular blocking detachments was quietly dropped; by October 1944, the units were officially disbanded.[114][115]

See also

Footnotes

- Zetterling & Frankson 2012, p. 253.

- Mercatante (2012). Why Germany Nearly Won: A New History of the Second World War in Europe. Abc-Clio. p. 105. ISBN 978-0313395932.

- Stahel, David (2013). Operation Typhoon: Hitler's March on Moscow, October 1941. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1107035126.

- Stahel, David (2011). Kiev 1941. Cambridge University Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-1139503600.

- Glantz, David M. (2001). Barbarossa: Hitler's Invasion of Russia 1941. Tempus Publishing Ltd. p. 141. ISBN 978-0739417973.

- Glantz (1995), p. 78.

- Liedtke 2016, p. 148.

- Bergström 2007 p. 90.

- Williamson 1983, p. 132.

- Both sources use Luftwaffe records. The often quoted figures of 900–1,300 do not correspond with recorded Luftwaffe strength returns. Sources: Prien, J.; Stremmer, G.; Rodeike, P.; Bock, W. Die Jagdfliegerverbande der Deutschen Luftwaffe 1934 bis 1945, parts 6/I and II; U.S National Archives, German Orders of Battle, Statistics of Quarter Years.

- Bergström 2007, p. 111.

- Liedtke, Enduring the Whirlwind, 3449. Kindle.

- "РОССИЯ И СССР В ВОЙНАХ XX ВЕКА. Глава V. ВЕЛИКАЯ ОТЕЧЕСТВЕННАЯ ВОЙНА". rus-sky.com.

- "1941". Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.

- "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Исследования ]-- Мягков М.Ю. Вермахт у ворот Москвы, 1941-1942". militera.lib.ru.

- David M. Glantz. When Titans Clashed. pp. 298, 299.

- Shirer, William L. "24, Swedish (Book III)". The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. pp. 275–87.

- Bellamy 2007, p. 243.

- Bellamy 2007, p. 240.

- Alan F. Wilt. "Hitler's Late Summer Pause in 1941". Military Affairs, Vol. 45, No. 4 (December 1981), pp. 187–91

- Flitton 1994.

- Niepold, Gerd (1993). "Plan Barbarossa". In David M. Glantz (ed.). The Initial Period of War on the Eastern Front, 22 June – August 1941: Proceedings of the Fourth Art of War Symposium, Garmisch, FRG, October 1987. Cass series on Soviet military theory and practice. Vol. 2. Psychology Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0714633756.

- Glantz & House 1995, p. 293.

- Stahel, David (2014). Operacja "Tajfun" [Operation Typhoon: Hitler's March on Moscow, October 1941] (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. p. 89. ISBN 978-83-05-136402.

- Bergstöm 2007, p. 90.

- Guderian, pp. 307–309.

- Hardesty, 1991, p. 61.

- Bergström 2007, p. 118.

- Bergström 2007, pp. 90–91.

- Guderian, p. 307

- Clark Chapter 8,"The Start of the Moscow Offensive", p. 156 (diagram)

- Glantz, chapter 6, sub-ch. "Viaz'ma and Briansk", pp. 74 ff.

- Vasilevsky, p. 139.

- Guderian, p. 316.

- Clark, pp. 165–66.

- Guderian, p. 318.

- David M. Glantz. When Titans Clashed. pp. 80, 81.

- Zetterling & Frankson 2012, p. 100.

- Bergström 2007, p. 91.

- Geoffrey Jukes, The Second World War – The Eastern Front 1941–1945, Osprey, 2002, ISBN 1-84176-391-8, p. 29.

- Jukes, p. 31.

- Glantz, When Titans Clashed p. 336 n15.

- Smith, Howard K. (1942). Last Train from Berlin. Knopf. pp. 83–91.

- The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970–1979). 2010 The Gale Group, Inc.

- Zhukov, Georgy (1974). Marshal of Victory, Volume II. Pen and Sword Books Ltd. pp. 7, 19. ISBN 978-1781592915.

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 10.

- Plocher 1968, p. 231.

- Bergström 2007, p. 93

- Jukes, p. 32.

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 17.

- Marshal Zhukov's Greatest Battles p. 50.

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 18.

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 22.

- Braithwaite, pp. 184–210.

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 24.

- Guderian, pp. 329–330.

- Zhukov, tome 2, pp. 23–25.

- Glantz, chapter 6, sub-ch. "To the Gates", pp. 80ff.

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 27.

- Klink, pp. 574, 590–92

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 28.

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 30.

- Guderian, p. 345.

- Guderian, p. 340.

- Bellamy, Chris. Absolute War: Soviet Russia In The Second World War.

- Belov, p. 106.

- John S Harrel

- Beyda, Oleg (7 August 2016). "'La Grande Armée in Field Gray': The Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism, 1941". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 29 (3): 500–18. doi:10.1080/13518046.2016.1200393. S2CID 148469794.

- Henry Steele Commager, The Story of the Second World War, p. 144

- Christopher Argyle, Chronology of World War II Day by Day, p. 78

- Lejenäs, Harald (1989). "The Severe Winter in Europe 1941–42: The large scale circulation, cut-off lows, and blocking". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 70 (3): 271–81. Bibcode:1989BAMS...70..271L. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1989)070<0271:TSWIET>2.0.CO;2.

- Chew (1981), p. 34.

- Raus (2009), p. 89.

- Glantz, ch.6, subchapter "December counteroffensive", pp. 86ff.

- Moss (2005), p. 298.

- Chew (1981), p. 33.

- Stahel 2019, p. 317.

- Guderian, pp. 354–55.

- Iskander Kuzeev, "Moscow flood in autumn of 1941", Echo of Moscow, 30 June 2008

- Mikhail Arkhipov, "Flooding north of Moscow Oblast in 1941", Private blog, 2 October 2007

- Igor Kuvyrkov, "Moscow flood in 1941: new data", Moscow Volga channel, 23 February 2015

- Operational overview of military activities on Western Front in year 1941, Central Archive of the Soviet Ministry of Defence, Stock 208 inventory 2511 case 1039, p. 112

- Goldman p. 177

- Zhukov, tome 2, p. 37.

- History of the Second World War. Marshall Cavendish". pp. 29–32.

- Guderian, pp. 353–55.

- Guderian, p. 354.

- "Battle of Moscow". WW2DB. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Guderian, pp. 360–61.

- STAHEL, DAVID. (2020). RETREAT FROM MOSCOW : a new history of germany's winter campaign 1941-1942. PICADOR. ISBN 978-1-250-75816-3. OCLC 1132236223.

- Guderian, pp. 363–64.

- Bergström", Christer. Operation Barbarossa 1941: Hitler Against Stalin. p. 245.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Moscow, 1973–78, entry "Battle of Moscow 1941–42"

- Guderian, p. 359.

- "Walther von Brauchitsch | German military officer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Glantz and House 1995, pp. 88–90.

- Bergstrom 2003, p. 297.

- Bergström 2007, pp. 112–13.

- Bergström 2003, p. 299.

- Glantz and House 1995, pp. 91–97.

- Guderian, p. 365.

- Roberts, Cynthia A. (December 1995). "Planning for war: the Red Army and the catastrophe of 1941". Europe-Asia Studies. 47 (8): 1293–1326. doi:10.1080/09668139508412322. JSTOR 153299.

Marshal Georgii K. Zhukov, who had pressed Stalin on several occasions to alert and reinforce the army, nonetheless recalled the shock of the German attack when he noted that 'neither the defence commissariat, myself, my predecessors B.M. Shaposhnikov and K.A. Meretskov, nor the General Staff thought the enemy could concentrate such a mass of ... forces and commit them on the first day ...

- Zhukov, tome 2, pp. 43–44.

- T.S. (17 August 1942). "Movie Review: Moscow Strikes Back (1942) 'Moscow Strikes Back,' Front-Line Camera Men's Story of Russian Attack, Is Seen at the Globe". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Rodric Braithwaite, "Moscow 1941: A City and Its People at War", p. 345.

- For example "Russia re-enacts historic WW2 parade in Moscow". BBC News. 7 November 2019.

- AnydayGuide. "Anniversary of the 1941 October Revolution Day Parade in Russia / November 7, 2016". AnydayGuide. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- "Russia marks anniversary of 1941 military parade". Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- John Erickson, Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies, table 12.4

- Glantz, Table B

- "Heeresarzt 10-Day Casualty Reports per Army/Army Group, 1941". Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- Jones, Michael (2009). The Retreat. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 107, 126–27, 292. ISBN 978-0719569265.

- Antony Beevor, "The Second World War". pg. 283

- Звягинцев, Вячеслав Егорович (2006). Война на весах Фемиды: война 1941-1945 гг. в материалах следственно-судебных дел (in Russian). Терра. ISBN 978-5-275-01309-2.

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. Yale University Press. p. 132.

Sources

- Bellamy, Chris (2007). Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-72471-8..

- Braithwaite, Rodric. Moscow 1941: A City and Its People at War. London: Profile Books Ltd., 2006. ISBN 1-86197-759-X.

- Collection of legislative acts related to State Awards of the USSR (1984), Moscow, ed. Izvestia.

- Belov, Pavel Alekseevich (1963). Za nami Moskva. Moscow: Voenizdat.

- Bergström, Christer (2007). Barbarossa – The Air Battle: July–December 1941. London: Chevron/Ian Allan. ISBN 978-1-85780-270-2.

- Boog, Horst; Förster, Jürgen; Hoffmann, Joachim; Klink, Ernst; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd R. (1998). Attack on the Soviet Union. Germany and the Second World War. Vol. IV. Translated by Dean S. McMurry; Ewald Osers; Louise Willmot. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822886-8.

- Chew, Allen F. (December 1981). "Fighting the Russians in Winter: Three Case Studies" (PDF). Leavenworth Papers. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas (5). ISSN 0195-3451. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Erickson, John; Dilks, David (1994). Barbarossa: The Axis and the Allies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0504-0.

- Glantz, David M.; House, Jonathan M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0717-4.

- Goldman, Stuart D. (2012). Nomonhan, 1939; The Red Army's Victory That Shaped World War II. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-098-9.

- Heinz Guderian, Воспоминания солдата (Memoirs of a soldier), Smolensk, Rusich, 1999 (Russian translation of Guderian, Heinz (1951). Erinnerungen eines Soldaten. Heidelberg: Vowinckel.)

- Hill, Alexander (2009)."British Lend-Lease Tanks and the Battle of Moscow, November–December 1941 – Revisited." Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 22: 574–87. doi:10.1080/13518040903355794.

- Hill, Alexander (2017), The Red Army and the Second World War, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-1070-2079-5.

- Hardesty, Von. Red Phoenix. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991. ISBN 1-56098-071-0

- Jukes, Geoffrey (2002). The Second World War: The Eastern Front 1941–1945. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-391-0.

- Liedtke, Gregory (2016). Enduring the Whirlwind: The German Army and the Russo-German War 1941–1943. Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1910777756.

- Lopukhovsky, Lev (2013). Britton Stuart (ed.). The Viaz'ma Catastrophe, 1941 The Red Army's Disastrous Stand Against Operation Typhoon. Translated by Britton Stuart. West Midlands: Helion. ISBN 978-1-908916-50-1.

- Moss, Walter G. (2005). A History of Russia: Since 1855. Anthem Russian and Slavonic studies. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-034-1.

- Nagorski, Andrew (2007). The Greatest Battle: Stalin, Hitler, and the Desperate Struggle for Moscow That Changed the Course of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-8110-2.

- Flitton, Dave (director, producer, writer) (1994). The Battle of Russia (television documentary). US: PBS.

- Plocher, Hermann (1968). Luftwaffe versus Russia, 1941. New York: USAF: Historical Division, Arno Press.

- Prokhorov, A. M. (ed.). Большая советская энциклопедия (in Russian). Moscow. or Prokhorov, A. M., ed. (1973–1978). Great Soviet Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan.

- Raus, Erhard; Newton, Steven H. (2009). Panzer Operations: The Eastern Front Memoir of General Raus, 1941–1945. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-3970-7.

- Reinhardt, Klaus. Moscow: The Turning Point? The Failure of Hitler's Strategy in the Winter of 1941–42. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1992. ISBN 0-85496-695-1.

- Sokolovskii, Vasilii Danilovich (1964). Razgrom Nemetsko-Fashistskikh Voisk pod Moskvoi (with map album). Moscow: VoenIzdat. LCCN 65-54443.

- Stahel, David (2019). Retreat from Moscow: A New History of Germany's Winter Campaign, 1941–1942. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-03742-49526.

- Stahel, David (2015). The Battle for Moscow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107087606.

- Tooze, Adam (2006). The Wages of Destruction: The making and breaking of the Nazi economy. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-100348-1.

- Vasilevsky, A. M. (1981). Дело всей жизни (Lifelong cause) (in Russian). Moscow: Progress. ISBN 978-0-7147-1830-9.

- Williamson, Murray (1983). Strategy for Defeat: The Luftwaffe 1933–1945. Maxwell AFB: Air University Press. ISBN 978-1-58566-010-0.

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1987). Moscow to Stalingrad. Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 978-0880292948.

- Zetterling, Niklas; Frankson, Anders (2012). The Drive on Moscow, 1941: Operation Taifun and Germany's First Great Crisis of World War II. Havertown: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61200-120-3.

- Жуков, Г. К. (2002). Воспоминания и размышления. В 2 т. (in Russian). М. ISBN 978-5-224-03195-5. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (English translation Zhukov, G. K. (1971). The Memoirs of Marshal Zhukov. London: Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-61924-0.)

External links

- "Operation Typhoon": Video on YouTube, lecture by David Stahel, author of Operation Typhoon. Hitler's March on Moscow (2013) and The Battle for Moscow (2015); via the official channel of USS Silversides Museum

- Map: Deployment of troops before the battle of Moscow

- Map (detailed): Battle of Moscow 1941. German offensive

- WW2DB: Battle of Moscow