Erich Hoepner

Erich Kurt Richard Hoepner (14 September 1886 – 8 August 1944) was a German general during World War II. An early proponent of mechanisation and armoured warfare, he was a Wehrmacht army corps commander at the beginning of the war, leading his troops during the invasion of Poland and the Battle of France.

Erich Hoepner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 September 1886 Frankfurt (Oder), Brandenburg, Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 8 August 1944 (aged 57) Plötzensee Prison, Berlin, Nazi Germany |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ | Army |

| Years of service | 1905–42 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | World War I

|

| Awards | Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross |

Hoepner commanded the 4th Panzer Group on the Eastern Front during Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. During the invasion of Poland, he resisted mistreatment and murder of prisoners of war, but in Russia, units under his authority closely cooperated with the Einsatzgruppen and he implemented the Commissar Order that directed Wehrmacht troops to summarily execute Red Army political commissars immediately upon capture. Hoepner's Panzer group, along with the 3rd Panzer Group, spearheaded the advance on Moscow in Operation Typhoon, the failed attempt to seize the Soviet capital.

Dismissed from the Wehrmacht after the failure of the 1941 campaign, Hoepner restored his pension rights through a lawsuit. He was implicated in the failed 20 July plot against Adolf Hitler and executed in 1944.

Early years and World War I

Hoepner was born in Frankfurt (Oder), the son of Prussian medical officer Kurt Hoepner. He was commissioned into the Prussian Army as a cavalry lieutenant in 1906, joining the Schleswig-Holstein Dragoons Regiment No. 13 (de). In 1911 he attended the Prussian Staff College and was assigned to the General Staff of the XVI Corps. When the First World War began he was assigned to the Western Front, serving as a company commander and staff officer for several corps and armies. He fought with the 105th Infantry Division in the German spring offensive of 1918, ending the war in the cavalry.[1][2]

Interwar period

Hoepner remained in the Reichswehr during the Weimar Republic period.[1] He was promoted to the rank of Generalmajor in 1936 and in 1938 was given command of the 1st Light Division (later 6th Panzer Division), an early armoured unit that was part of the nucleus of the expanding German Panzerwaffe. Claus von Stauffenberg served on Hoepner's divisional staff.[3] After the Blomberg–Fritsch affair in early 1938, the result of which was the subjugation of the Wehrmacht to dictator Adolf Hitler, and as the Sudetenland Crisis unfolded, Hoepner joined the Oster conspiracy. The group planned to kill Hitler and overthrow the Nazi SS, should Hitler move to invade Czechoslovakia. Hoepner's role in the plan was to lead the 1st Light Division toward Berlin and seize key objectives against the SS forces in the city. The conspiracy collapsed with the appeasement by Neville Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier and the signing of the Munich Agreement. Upon his rival Heinz Guderian's assumption of command of the XIX Army Corps, Hoepner replaced him as the commander of the XVI Army Corps. He led the corps in the occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 and was promoted the next month to General of the Cavalry.[4]

World War II

Invasion of Poland and Battle of France

Hoepner commanded the XVI Army Corps in the Invasion of Poland where he covered the 230 km (140 mi) to Warsaw in only a week as part of the 10th Army.[5] Hoepner and his corps were transferred to the 6th Army for the Battle of France, where he spearheaded attacks on Liège and then Dunkirk and Dijon. On 22 May, the SS Division Totenkopf was assigned to XVI Corps, starting what was to be a long period of friction and mutual dislike between Hoepner and the SS. During the Battle of Dunkirk, rumours began to spread of SS troops mistreating prisoners and on 24 May Hoepner issued a special order to his units that any soldiers caught mistreating prisoners would face immediate court-martial.[6]

Three days later troops from the SS Division Totenkopf killed almost a hundred British prisoners in the Le Paradis massacre. When word of the massacre reached Hoepner he ordered an investigation into the allegations, demanding that the SS division commander, Theodor Eicke be dismissed if evidence could be found that British prisoners had been mistreated or killed by SS forces. Eicke made an excuse to Himmler that the British had used dum-dum bullets against his forces. He and the Totenkopf unit suffered no consequences and the matter was officially forgotten.[7] However, Hoepner continued to hold a personal and professional dislike of Eicke, calling him a "butcher" for his disregard of casualties. He also maintained his existing low opinion of the Waffen-SS.[8]

War against the Soviet Union

After the conclusion of the fighting in France, Hoepner was promoted to the rank of Generaloberst in July 1940.[1] The German High Command had commenced planning for Operation Barbarossa,[9] and Hoepner was appointed to command the 4th Panzer Group that was to drive toward Leningrad as part of Army Group North under Wilhelm von Leeb.[2] On 30 March 1941, Hitler delivered a speech to about two hundred senior Wehrmacht officers where he laid out his plans for an ideological war of annihilation (Vernichtungskrieg) against the Soviet Union.[10] He stated that "wanted to see the impending war against the Soviet Union conducted not according to the military principles, but as a war of extermination" against an ideological enemy, whether military or civilian. Many Wehrmacht leaders, including Hoepner, echoed the sentiment.[11] As a commander of the 4th Panzer Group, he issued a directive to his troops:

The war against Russia is an important chapter in the struggle for existence of the German nation. It is the old battle of Germanic against Slav peoples, of the defence of European culture against Muscovite-Asiatic inundation, and the repulse of Jewish-Bolshevism. The objective of this battle must be the destruction of present-day Russia and it must therefore be conducted with unprecedented severity. Every military action must be guided in planning and execution by an iron will to exterminate the enemy mercilessly and totally. In particular, no adherents of the present Russian-Bolshevik system are to be spared.

— 2 May 1941[12]

The order was transmitted to the troops on Hoepner's initiative, ahead of the official OKW (Wehrmacht High Command) directives that laid the groundwork for the war of extermination, such as the Barbarossa Decree of 13 May 1941 and other orders. Hoepner's directive predates the first OKH (Army High Command) draft of the Commissar Order.[14] Jürgen Förster wrote that Hoepner's directive represented an "independent transformation of Hitler's ideological intentions into an order" and illustrated a "degree of conformity or affinity" between Hitler and military leadership, which provided a sufficient basis for collaboration in the aims of conquest and annihilation against a perceived threat from the Soviet Union.[14]

Advance on Leningrad

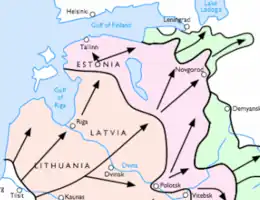

The 4th Panzer Group consisted of the LVI Panzer Corps (Erich von Manstein) and the XLI Panzer Corps (Georg-Hans Reinhardt).[15] The Army Group was to advance through the Baltic States to Leningrad. Barbarossa commenced on 22 June 1941 with a massive German attack along the whole front line. The 4th Panzer Group headed for the Dvina River to secure the bridges near the town of Daugavpils.[16] The Red Army mounted a number of counterattacks against the XLI Panzer Corps, leading to the Battle of Raseiniai.[17]

After Reinhardt's corps closed in, the two corps were ordered to encircle the Soviet formations around Luga. Again having penetrated deep into the Soviet lines with unprotected flanks, Manstein's corps was the target of a Soviet counteroffensive from 15 July at Soltsy by the Soviet 11th Army. Manstein's forces were badly mauled and the Red Army halted the German advance at Luga.[18] Ultimately, the army group defeated the defending Soviet Northwestern Front, inflicting over 90,000 casualties and destroying more than 1,000 tanks and 1,000 aircraft, then advanced northeast of the Stalin line.[19]

During his command on the Eastern Front, Hoepner demanded "ruthless and complete destruction of the enemy."[20] On 6 July 1941, Hoepner issued an order to his troops instructing them to treat the "loyal population" fairly, adding that "individual acts of sabotage should simply be charged to communists and Jews".[21] As with all German armies on the Eastern Front, Hoepner's Panzer Group implemented the Commissar Order that directed Wehrmacht troops to execute Red Army political officers immediately upon capture, contravening the accepted laws of war.[22] Between 2 July and 8 July, the 4th Panzer Group shot 101 Red Army political commissars, with the bulk of the executions coming from the XLI Panzer Corps.[21] By 19 July, 172 executions of commissars had been reported.[23]

By mid-July, the 4th Panzer Group seized the Luga bridgehead and had plans to advance on Leningrad. The staff and detachments 2 and 3 of Einsatzgruppe A, one of the mobile killing squads following the Wehrmacht into the occupied Soviet Union, were brought up to the Luga district with assistance from the army. "The movement of Einsatzgruppe A—which the army intended to use in Leningrad—was effected in agreement with Panzer Group 4 and at their express wish", noted Franz Walter Stahlecker, the commander of Einsatzgruppe A.[24] Stahlecker described army co-operation as "generally very good" and "in certain cases, as for example, with Panzer Group 4 under the command of General Hoepner, extremely close, one might say even warm."[25]

By late July, Army Group North positioned 4th Panzer Group's units south and east of Narva, Estonia, where they could begin an advance on Leningrad in terrain conditions relatively suitable for armoured warfare. By that time, however, the army group lacked the strength to take Leningrad, which continued to be a high priority for the German high command. A compromise solution was worked out whereas the infantry would attack north from both sides of Lake Ilmen, while the Panzer Group would advance from its current position. Hoepner's forces began their advance on August 8, but the attack ran into determined Soviet defences. Elsewhere, Soviet counter-attacks threatened Leeb's southern flank. By mid to late August, the German forces were making gains again, with the 4th Panzer Group taking Narva on 17 August.[26]

On 29 August, Leeb issued orders for the blockade of Leningrad in anticipation that the city would soon be abandoned by the Soviets. On September 5, Hitler ordered Hoepner's 4th Panzer Group and an air corps transferred to Army Group Centre effective 15 September, in preparation for Operation Typhoon, the German assault on Moscow. Leeb objected and was given a reprieve in the transfer of his mobile forces, with the view of making one last push towards Leningrad. The 4th Panzer Group was to be the main attacking force, which reached south of the Neva River, where it was faced with strong Soviet counter-attacks. By 24 September, Army Group North halted its advance and transferred the 4th Panzer Group to Army Group Centre.[27]

Battle of Moscow

As part of Operation Typhoon, the 4th Panzer Group was subordinated to the 4th Army under the command of Günther von Kluge. In early October, the 4th Panzer Group completed the encirclement at Vyazma. Kluge instructed Hoepner to pause the advance, much to the latter's displeasure, as his units were needed to prevent break-outs of Soviet forces. Hoepner was confident that the clearing of the pocket and the advance on Moscow could be undertaken at the same time and viewed Kluge's actions as interference, leading to friction and "clashes" with his superior, as he wrote in a letter home on 6 October.[28] Hoepner did not seem to appreciate that his units were very short on fuel; the 11th Panzer Division, reported having no fuel at all. Only the 20th Panzer Division was advancing towards Moscow amid deteriorating road conditions.[29]

Once the Vyazma pocket was eliminated, other units were able to advance on 14 October. Heavy rains and onset of the rasputitsa (roadlessness) caused frequent damage to tracked vehicles and motor transport further hampering the advance.[30] By early November, Hoepner's forces were depleted from earlier fighting and the weather but he, along with other Panzer Group commanders and Fedor von Bock, commander of Army Group Center, was impatient to resume the offensive. In a letter home, Hoepner stated that just two weeks of the frozen ground would allow his troops to surround Moscow, not taking into account the stiffening Soviet resistance and the condition of his units.[31] David Stahel wrote that Hoepner displayed "steadfast determination, and often excessive confidence" during that period.[32]

On 17 November the 4th Panzer Group attacked again towards Moscow alongside the V Army Corps of the 4th Army, as part of the continuation of Operation Typhoon by Army Group Centre. The Panzer Group and the army corps represented Kluge's best forces, most ready for a continued offensive. In two weeks' fighting, Hoepner's forces advanced 60 km (37 mi) (4 km (2.5 mi) per day).[33] Lacking strength and mobility to conduct battles of encirclement, the Group undertook frontal assaults which proved increasingly costly.[34] A lack of tanks, insufficient motor transport and a precarious supply situation, along with tenacious Red Army resistance and the air superiority achieved by Soviet fighters hampered the attack.[35]

The 3rd Panzer Group further north saw slightly better progress, averaging 6 km (3.7 mi) a day. The attack by the 2nd Panzer Group on Tula and Kashira, 125 km (78 mi) south of Moscow, achieved only fleeting and precarious success, while Guderian vacillated between despair and optimism, depending on the situation at the front.[36] Facing pressure from the German High Command, Kluge finally committed his weaker south flank to the attack on 1 December. In the aftermath of the battle, Hoepner and Guderian blamed slow commitment of the south flank of the 4th Army to the attack for the German failure to reach Moscow. Stahel wrote that this assessment grossly overestimated the capabilities of Kluge's remaining forces.[37] It also failed to appreciate the reality that Moscow was a metropolis that German forces lacked the numbers to encircle. With the outer defensive belt completed by 25 November, Moscow was a fortified position which the Wehrmacht lacked the strength to take in a frontal assault.[38]

As late as 2 December, Hoepner urged his troops forward stating that "the goal [the encirclement of Moscow] can still be achieved". The next day, he warned Kluge that failure to break off the attack would "bleed white" his formations and make them incapable of defence. Kluge was sympathetic since the south flank of the 4th Army had already had to retreat under Red Army pressure and was on the defensive.[39] Hoepner was ordered to pause his attack, with the goal of resuming it on 6 December. In a letter home, Hoepner blamed Kluge for the inability to seize Moscow, "I alone came to within thirty kilometres to Moscow ... It's very bitter ... in the deciding moment to be left in the lurch and forced to resignation". Such "blinkered thinking" on Hoepner's part was common among the German commanders in charge of the operation, which in Stahel's opinion "even before it began, made little practical sense".[40] On 5 December 1941, with orders to attack the next day, Hoepner called a conference of chiefs-of-staff of his five corps. The reports were grim: only four divisions were deemed capable of attack, three of these with limited objectives. The attack was called off; the Red Army launched its winter counter-offensive on the same day.[41]

Dismissal and 20 July plot

In January 1942, Hoepner requested permission from Kluge, the new commander of Army Group Centre, to withdraw his over-extended forces. Kluge advised him that he would discuss the matter with Hitler and ordered Hoepner to get ready. Assuming that Hitler's permission was on the way and not wanting to risk the matter any longer, Hoepner ordered his troops to withdraw on 8 January 1942. Afraid of what Hitler might think, Kluge immediately reported Hoepner, causing Hitler's fury. Hoepner was dismissed from the Wehrmacht on the same day.[42] Hitler directed that Hoepner be deprived of his pension and denied the right to wear his uniform and medals, contravening the law and Wehrmacht regulations.[43] Hoepner filed a lawsuit against the Reich to reclaim his pension. Judges at the time could not be dismissed, even by Hitler, and Hoepner won his case.[44]

Hoepner was a participant in the 20 July plot against Hitler in 1944 and after the coup failed he was arrested and tortured by the Gestapo. He refused an opportunity to commit suicide and demanded a trial. A summary trial was conducted by the Volksgerichtshof and Hoepner was verbally attacked and sentenced to death. Like other defendants, including Erwin von Witzleben, Hoepner was humiliated during the trial by being made to wear ill-fitting clothes, and not being allowed to have his false teeth. Judge Roland Freisler berated Hoepner, but, in an extremely unusual move given his very aggressive personality, he objected to him being made to dress in such a way.[45] Hoepner was hanged by wire mounted from meat hooks on 8 August, at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin.[46]

Under the Nazi practice of Sippenhaft (collective punishment) Hoepner's wife, daughter, son (a major in the army), brother and sister were arrested.[47] The women were sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp. His sister was soon released but Frau Hoepner and her daughter were placed in the notorious Strafblock for four weeks' additional punishment.[48][49] Hoepner's son was first held at a specially created camp at Küstrin (now Kostrzyn nad Odrą) and then sent to Buchenwald concentration camp.[50]

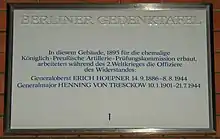

Commemoration

In 1956, a school in Berlin was named after Hoepner because he had joined the 20 July plot and was executed by the Nazi regime. The school voted to drop the name in 2008. In 2009, the school director attested to the fact that "the name had been controversial from the start and was repeatedly debated".[51]

Awards

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 27 October 1939 as General of the Cavalry and commander of XVI. Armee-Korps[52]

Citations

- Tucker 2016, p. 793.

- Zabecki 2014, p. 615.

- Mitcham 2006, p. 76.

- Fest 1997, p. 68.

- Tucker 2016, pp. 793–794.

- English 2011, p. 14.

- Sydnor 1977, pp. 108–109.

- English 2011, pp. 11–12.

- Evans 2008, p. 160.

- Förster 1998, pp. 496–497.

- Crowe 2013, p. 90.

- Burleigh 1997, p. 76.

- see also www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de

- Förster 1998, pp. 519–521.

- Melvin 2010, pp. 198–199.

- Melvin 2010, pp. 205.

- Melvin 2010, pp. 209–210.

- Melvin 2010, pp. 217–218.

- Glantz 2012.

- Friedmann, Jan (4 February 2009). "Dubious Role Models: Study Reveals Many German Schools Still Named After Nazis". Spiegel.de. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- Stein 2007, p. 301.

- Stahel 2015, p. 28.

- Lemay 2010, p. 252.

- Jones 2008, p. 35.

- Stahel 2015, p. 37.

- Megargee 2006, pp. 104–106.

- Megargee 2006, pp. 115–116.

- Stahel 2013, pp. 74–75, 95.

- Stahel 2013, p. 95.

- Stahel 2013, pp. 173–174.

- Stahel 2015, pp. 78–80.

- Stahel 2015, p. 77.

- Stahel 2015, p. 228.

- Stahel 2015, p. 223.

- Stahel 2015, pp. 240–244.

- Stahel 2015, p. 186−189, 228.

- Stahel 2015, pp. 229–230.

- Stahel 2015, pp. 235–237, 250.

- Stahel 2015, pp. 295–296.

- Stahel 2015, pp. 304–305.

- Stahel 2015, pp. 306–307.

- Evans 2008, p. 206.

- Lemay 2010, p. 219.

- Kershaw 2009, pp. 837, 899.

- Gill 1994, p. 256.

- Tucker 2016, p. 794.

- Loeffel 2012, p. 130.

- Ravensbruck: Life and Death in Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women by Sarah Helm

- Helm 2015, pp. 396–397.

- Loeffel 2012, pp. 162–164.

- Crossland, David (16 February 2009). "Nazi era lives on in German schools". thenational.ae. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017.

- Fellgiebel 2000, p. 230.

References

- Burleigh, Michael (1997). Ethics and Extermination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511806162. ISBN 9780521582117.

- Crowe, David M. (2013). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-98681-2.

- English, John A. (2011). Surrender Invites Death: Fighting the Waffen SS in Normandy. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4437-9.

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War: 1939–1945. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Fest, Joachim (1997). Plotting Hitler's Death: The Story of German Resistance. Basingstoke, United Kingdom: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-5648-8.

- Förster, Jürgen (1998). "Operation Barbarossa as a War of Conquest and Annihilation". In Boog, Horst; Förster, Jürgen; Hoffmann, Joachim; Klink, Ernst; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd R. (eds.). Germany and the Second World War: Attack on the Soviet Union. Vol. IV. Oxford and New York: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822886-8.

- Gill, Anton (1994). An Honourable Defeat, The Fight Against National Socialism in Germany 1933–1945. London: Mandarin. ISBN 978-0-7493-1457-6.

- Glantz, David (2012). Operation Barbarossa: Hitler's invasion of Russia 1941. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6070-3.

- Helm, Sarah (2015). If This Is A Woman. Inside Ravensbrück: Hitler's Concentration Camp for Women. London, United Kingdom: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0538-4.

- Jones, Michael (2008). Leningrad: State of Siege. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01153-7.

- Kershaw, Ian (2009). Hitler. London, United Kingdom: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-103588-8.

- Lemay, Benoit (2010). Erich Von Manstein: Hitler's Master Strategist. Philadelphia, PA: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-935149-55-2.

- Loeffel, Robert (2012). Family Punishment in Nazi Germany: Sippenhaft, Terror and Myth. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-34305-4.

- Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2006). War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4482-6.

- Melvin, Mungo (2010). Manstein: Hitler's Greatest General. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84561-4.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2006). Panzer Legions: A Guide to the German Army Tank Divisions of World War II and Their Commanders. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-1-4617-5143-4.

- Patzwall, Klaus D.; Scherzer, Veit (2001). Das Deutsche Kreuz 1941–1945 Geschichte und Inhaber Band II [The German Cross 1941–1945 History and Recipients] (in German). Vol. 2. Norderstedt, Germany: Verlag Klaus D. Patzwall. ISBN 978-3-931533-45-8.

- Stahel, David (2015). The Battle for Moscow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08760-6.

- Stahel, David (2013). Operation Typhoon: Hitler's March on Moscow, October 1941. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03512-6.

- Stein, Marcel (2007). Field Marshal von Manstein: The Janushead – A Portrait. Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-906033-02-6.

- Sydnor, Charles (1977). Soldiers of Destruction: The SS Death's Head Division, 1933–1945. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ASIN B001Y18PZ6.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2016). World War II: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-969-6.

- Zabecki, David T. (2014). Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-981-3.

External links

- Operation Typhoon on YouTube, lecture by the historian David Stahel discussing operations of the 4th Panzer Group; via the official channel of USS Silversides Museum

- Biography at the German Historical Museum of Berlin (in German)

- Umstrittener Patron, article in Der Tagesspiegel (in German)