Philippine resistance against Japan

During the Japanese occupation of the islands in World War II, there was an extensive Philippine resistance movement (Filipino: Kilusan ng Paglaban sa Pilipinas), which opposed the Japanese and their collaborators with active underground and guerrilla activity that increased over the years. Fighting the guerrillas – apart from the Japanese regular forces – were a Japanese-formed Bureau of Constabulary (later taking the name of the old Philippine Constabulary during the Second Republic),[12][13] the Kenpeitai (the Japanese military police),[12] and the Makapili (Filipinos fighting for the Japanese).[14] Postwar studies estimate that around 260,000 people were organized under guerrilla groups and that members of anti-Japanese underground organizations were more numerous.[15][16] Such was their effectiveness that by the end of World War II, Japan controlled only twelve of the forty-eight provinces.

| Philippine resistance against Japan Paglaban ng Pilipinas sa mga Hapon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||||

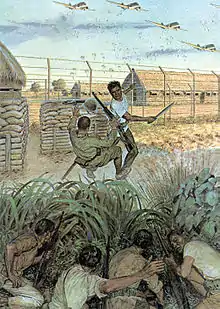

Propaganda poster depicting the Philippine resistance movement | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Moro people[lower-alpha 2] | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Moro-Bolo Battalion Maranao Militia and others... | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Unknown Japanese 30,000 Constabulary[4] 6,000 Makapili[5] |

30,000 guerrillas in ten sectors (spring 1944)[6] ~260,000 formally recognized members of the pro-US resistance following the war[7] ~30,000 Hukbalahap fighters[7] ~30,000 Moro Juramentados[7] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 8,000–10,000 dead (before the Allied invasion in October 1944)[7][8] |

8,000 dead (1942-1945)[9] | ||||||||

| Around 530,000[10] to 1,000,000[9][11] Filipinos died during the Japanese occupation. | |||||||||

Select units of the resistance would go on to be reorganized and equipped as units of the Philippine Army and Constabulary.[17] The United States Government officially granted payments and benefits to various ethnicities who have fought with the Allies by the war's end. However, only the Filipinos were excluded from such benefits, and since then these veterans have made efforts in finally being acknowledged by the United States. Some 277 separate guerrilla units made up of 260,715 individuals were officially recognized as having fought in the resistance movement.[18]

Background

The attack on Pearl Harbor (called Hawaii Operation or Operation AI[19][20] by the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters) was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941 (December 8 in Japan and the Philippines).[21][22] The attack was intended as a preventive action in order to keep the U.S. Pacific Fleet from interfering with military actions Japan was planning in Southeast Asia against the overseas territories of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.[23]

Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese operations to invade the Commonwealth of the Philippines began. Twenty-five twin engine planes bombed Tuguegarao and Baguio in the first preemptive strike in Luzon. The Japanese forces then quickly conducted a landing at Batan Island, and by December 17, General Masaharu Homma gave his estimate that the main component of the United States Air Force in the archipelago was destroyed. By January 2, Manila was under Japanese control and by January 9, Homma had cornered the remaining forces in Bataan. By April 9, the remaining of the combined American-Filipino force was forced to retire from Bataan to Corregidor. Meanwhile, Japanese invasions of Cebu (April 19) and Panay (April 20) were successful. By May 7, after the last of the Japanese attacks on Corregidor, General Jonathan M. Wainwright announced through a radio broadcast in Manila the surrender of the Philippines. Following Wainwright was General William F. Sharp, who surrendered Visayas and Mindanao on May 10.[24]

Afterwards came the Bataan Death March, which was the forcible transfer, by the Imperial Japanese Army, of 60,000 Filipino and 15,000 American prisoners of war after the three-month Battle of Bataan in the Philippines during World War II.[25] The death toll of the march is difficult to assess as thousands of captives were able to escape from their guards (although many were killed during their escapes), and it is not known how many died in the fighting that was taking place concurrently. All told, approximately 2,500–10,000 Filipino and 300–650 American prisoners of war died before they could reach Camp O'Donnell.[26]

Resistance in Luzon

USAFFE and American sponsored guerrillas

After Bataan and Corregidor, many who escaped the Japanese reorganized in the mountains as guerrillas still loyal to the U.S. Army Forces Far East (USAFFE). One example would be the unit of Ramon Magsaysay in Zambales, which first served as a supply and intelligence unit. After the surrender in May 1942, Magsaysay and his unit formed a guerrilla force which grew to a 10,000-man force by the end of the war.[27] Another was the Hunters ROTC which operated in the Southern Luzon area, mainly near Manila. It was created upon dissolution of the Philippine Military Academy in the beginning days of the war. Cadet Terry Adivoso refused to simply go home as cadets were ordered to do, and began recruiting fighters willing to undertake guerrilla action against the Japanese.[28][29] This force would later be instrumental, providing intelligence to the liberating forces led by General Douglas MacArthur, and took an active role in numerous battles, such as the Raid at Los Baños. When war broke out in the Philippines, some 300 Philippine Military Academy and ROTC cadets, unable to join the USAFFE units because of their youth, banded together in a common desire to contribute to the war effort throughout the Bataan campaign. The Hunters originally conducted operations with another guerrilla group known as the Marking Guerrillas, with whom they went about liquidating Japanese spies. Led by Miguel Ver, a PMA cadet, the Hunters raided the enemy-occupied Union College in Manila and seized 130 Enfield rifles.[30]

Also, before being proven false in 1985 by the United States Military, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos claimed that he had commanded a 9,000-strong guerrilla force known as the Maharlika Unit.[31] Marcos also used maharlika as his personal pseudonym; depicting himself as a bemedalled anti-Japanese Filipino guerrilla fighter during World War II.[32][33] Marcos told exaggerated tales and exploits of himself fighting the Japanese in his self-published autobiography Marcos of the Philippines which was proven to be fiction.[34] His father, Mariano Marcos, did however collaborate with the Japanese and was executed by Filipino guerillas in April 1945 under the command of Colonel George Barnett, and Ferdinand himself was accused of being a collaborator as well.[35][36]

In July 1942, South West Pacific Area (SWPA) became aware of the resistance movements forming in occupied Philippines through attempted radio communications to Allies outside of the Philippines; by late 1942, couriers had made it to Australia confirming the existence of the resistance.[37] By December 1942, SWPA sent Captain Jesús A. Villamor to the Philippines to make contact with guerrilla organizations, eventually developing extensive intelligence networks including contacts within the Second Republic Government.[37][38][lower-alpha 3] A few months later SWPA sent Lieutenant Commander Chick Parsons, who returned to the Philippines in early 1943, vetting guerrilla leaders and established communications and supply for them with SWPA.[2][39] Through the Allied Intelligence Bureau's Philippine Regional Section, SWPA sent operatives and equipment into the Philippines to supply and assist guerrilla organizations, often by submarine.[37][40] The large cruiser submarines USS Narwhal and USS Nautilus, with a high capacity for personnel and supplies, proved especially useful in supporting the guerrillas.[41] Beginning in mid-1943, the assistance to the guerrillas in the Philippines became more organized, with the formation of the 5217th Reconnaissance Battalion, which was largely composed of volunteer Filipino Americans from the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments, which were established and organized in California.[42]

In Nueva Ecija, guerrillas led by Juan Pajota and Eduardo Joson protected the U.S. Army Rangers and Alamo Scouts who were conducting a rescue mission of Allied POWs from a counterattack by Japanese reinforcements.[43] Pajota and the Filipino guerrillas received Bronze Stars for their role in the raid.[44] Among the guerrilla units, the Blue Eagles were a specialized unit established for landmine and sniper detection, as well as in hunting Japanese spies who had blended in with the civilian population.[45]

Nonetheless, Japanese crackdowns on these guerrillas in Luzon were widespread and brutal. The Imperial Japanese Army, Kenpeitai and Filipino collaborators hunted down resistance fighters and anyone associated with them.[46] One example happened to resistance leader Wenceslao Vinzons, leader of the successful guerilla movement in Bicol.[47][48] After being betrayed to the Japanese by a Japanese collaborator, Vinzons was tortured to give up information on his resistance movement. Vinzons however refused to cooperate, and he and his family, consisting of his father Gabino, his wife Liwayway, sister Milagros and children Aurora and Alexander, were bayoneted to death.

Hukbalahap resistance

As originally constituted in March 1942, the Hukbalahap was to be part of a broad united front resistance to the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.[49] This original intent is reflected in its name: "Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon", which was "People's Army Against the Japanese" when translated into English. The adopted slogan was "Anti-Japanese Above All".[50] The Huk Military Committee was at the apex of Huk structure and was charged to direct the guerrilla campaign and to lead the revolution that would seize power after the war.[50] Luis Taruc, a communist leader and peasant-organizer from a barrio in Pampanga, was elected as head of the committee and became the first Huk commander called "El Supremo".[50] Casto Alejandrino became his second-in-command.

The Huks began their anti-Japanese campaign as five 100-man units. They obtained needed arms and ammunition from Philippine army stragglers, who were escapees from the Battle of Bataan and deserters from the Philippine Constabulary, in exchange of civilian clothes. The Huk recruitment campaign progressed more slowly than Taruc had expected, due to competition with U.S. Army Forces Far East (USAFFE) guerrilla units in enlisting new soldiers. The U.S. units already had recognition among the islands, had trained military leaders, and an organized command and logistical system.[50] Despite being restrained by the American sponsored guerrilla units, the Huks nevertheless took to the battlefield with only 500 men and much fewer weapons. Several setbacks at the hands of the Japanese and with less than enthusiastic support from USAFFE units did not hinder the Huks growth in size and efficiency throughout the war, developing into a well-trained, highly organized force with some 15,000 armed fighters by war's end.[50] The Huks attacked both the Japanese and other non-Huk guerrillas.[1] One estimate alleges that the Huks killed 20,000 non-Japanese during the occupation.[51]

Ethnic Chinese resistance

Unique to other guerrillas in the Philippines were the Wha-Chi; a resistance unit composed of Filipino-Chinese and Chinese immigrants.[52] They were established from the Chinese General Labour Union of the Philippines and the Philippine branch of the Chinese Communist Party and reached a strength of 700 men.[3] The movement served under the Huks until around 1943, when they started operating independently. They were also aided by the American guerrilla forces.[53][54]

Resistance in Visayas

Various guerrilla groups also sprang out throughout the central islands of Visayas. Like those in Luzon, many of these Filipino guerrillas were trained by the Americans to fight in case the Japanese set their sights on the Visayas. These soldiers continued to fight even as the Americans surrendered the islands to the Japanese.[56]

One significant achievement for the resistance in Visayas was the capture of the "Koga Papers" by Cebuano guerrillas led by Lt. Col. James M. Cushing in April 1, 1944.[57][58] Named after Admiral Mineichi Koga, these papers contained vital battle plans and defensive strategies of the Japanese Navy (code-named the "Z Plan"), information on the overall strength of the Japanese fleet and naval air units, and most importantly the fact that the Japanese had already deduced MacArthur's initial plans to invade the Philippines through Mindanao. These papers came into Filipino possession when Koga's seaplane, en route to Davao, crashed on the Cebu coast at San Fernando in the early hours of April 1, killing him and others. Koga's body (and many surviving Japanese) washing ashore, the guerrillas captured 12 high-ranking officers, including Vice Admiral Shigeru Fukodome, Chief of Staff of the Combined Fleet.[57][58] On April 3,[59] Cebuano fishermen found the papers inside a floating briefcase, then handed them over to the guerrillas, whereupon the Japanese ruthlessly hunted down both the documents and their captured officers, burning villages and detaining civilians in the process. They ultimately forced the guerrillas to release their captives in order to stop the aggression, but Cushing managed to summon a submarine which transported the documents to Allied headquarters in Australia. The contents of the papers were a factor in MacArthur's decision to move his planned invasion site from Mindanao to Leyte, and also aided the Allies in the Battle of the Philippine Sea.[58]

Waray guerrillas under a former school teacher named Nieves Fernandez fought the Japanese in Tacloban.[55] Nieves extensively trained her men in combat skills and making of improvised weaponry, as well as leading her men in the front. With only 110 men, Nieves managed to take out over 200 Japanese soldiers during the occupation. The Imperial Japanese Army posted a 10,000 pesos reward on her head in the hopes of capturing her but to no avail. The main commander of the resistance movement in the Island of Leyte was Ruperto Kangleon, a former Filipino soldier turned resistance fighter and leader. After the fall of the country, he successfully escaped capture by the Japanese and established a united guerrilla front in Leyte. He and his men, the Black Army, were successful in pushing the Japanese from the mainland province and further into the coastlands of Southern Leyte. Kangleon's guerrillas provided intelligence for the American guerrilla leaders such as Wendell Fertig, and assisted in the subsequent Leyte Landing and the Battle of Leyte soon after.[60] The guerrillas in Leyte were also instrumental not only in the opposition against Japanese rule, but also in the safety and aid of the civilians living in the island. The book The Hidden Battle of Leyte: The Picture Diary of a Girl taken by the Japanese Military by Remedios Felias, a former comfort woman, revealed how the Filipino guerrillas saved the lives of many young girls raped or at risk of rape by the Japanese. In her vivid account of the Battle of Burauen, she recounts how the guerrillas managed to wipe out entire Japanese platoons in the various villages in the municipality, eventually saving the lives of many.[61]

Besides their guerrilla activities, these groups also participated in many pivotal battles during the liberation of the islands. In Cebu, guerrillas and irregulars under Lieutenant James M. Cushing and Basilio J. Valdes aided in the Battle for Cebu City.[62] They also captured Maj. Gen. Takeo Manjom and his 2,000 soldiers and munitions. Panay guerrillas under Col. Macario Peralta helped in the seizing of the Tiring Landing Field and Mandurriao district airfield during the Battle of the Visayas.[63] Major Ingeniero commanded the guerrilla forces in Bohol,[64] in which they were credited in the liberation of the island from Japanese outposts at a cost of only seven men.

Moro resistance in Mindanao

While Moro rebels were still unsuccessfully at war with the United States, the Japanese invasion became the new perceived threat to their religion and culture.[65] Some of those who opposed the occupation and fought for Moro nationalism, were Sultan Jainal Abirin II of Sulu, the Sulu Sultanate of the Tausug, and the Maranao Moros living around Lake Lanao and ruled by the Confederation of sultanates in Lanao led by Salipada Pendatun. Another anti-Japanese Moro unit, the Moro-Bolo Battalion led by Datu Gumbay Piang, consisted of about 20,000 fighting men made up of both Muslims and Christians. As their name suggests, these fighters were known visibly by their large bolos and kris.[66] The Japanese Major Hiramatsu, a propaganda officer, tried convincing Datu Busran Kalaw of Maranao to join their side as "brother Orientals". Kalaw sent a response which goaded Major Hiramatsu into sending a force of Japanese soldiers to attack him, whom Kalaw butchered completely with no survivors.[67][68] The juramentados brigands, who were veterans in fighting the Filipinos, Spanish and the Americans, now focused their assaults on the Japanese, using their traditional hit and run as well as suicide charges.[69] The Japanese were anxious of being attacked by the resistance, and they fought back by murdering innocent civilians and destroying properties.[70]

During these times, the Moros had no allegiance with the Filipinos and the Americans, and they were largely unwelcoming of their assistance. In many cases, they would even indiscriminately attack them as well, especially following the fall of Corregidor, and establishment of a truce with the Moros by Wendell Fertig in mid 1943.[2]: 11–15 The Moros also performed various cruelties during the war, such as thoughtlessly assaulting Japanese immigrants already living in Mindanao before the war.[71] The warlord Datu Busran Kalaw was known for boasting that he "fought both the Americans, Filipinos and the Japanese", which took the lives of both American and Filipino agents and the Japanese occupiers.[72] Nonetheless, the Americans respected the success of the Moros during the war. American POW Herbert Zincke recalled in his secret diary that the Japanese guarding him and other prisoners were scared of the Moro warriors and tried to keep as far away from them as possible to avoid getting attacked.[73] The American Captain Edward Kraus recommended Moro fighters for a suggested plan to capture an airbase in Lake Lanao before eventually driving the Japanese occupiers out of the Philippines. The Moro Datu Pino sliced the ears off Japanese and cashed them in with the American guerrilla leader Colonel Fertig at the exchange rate of a pair of ears for one bullet and 20 centavos.[74]

Recognition

_-_NARA_-_6921767_(page_225).jpg.webp)

"Give me ten thousand Filipinos and I shall conquer the world!"

—Gen. Douglas MacArthur during his liberation of the Philippines, highly impressed with the Filipinos who fought with him[75][76]

The Filipino guerrillas were successful in their resistance against the Japanese occupation. Of the 48 provinces in the Philippines, only 12 were in firm control of the Japanese.[77] Many provinces in Mindanao were already liberated by the Moros well before the Americans came, as well as major islands in the Visayas such as Cebu, Panay and Negros. During the occupation, many Filipino soldiers and guerrillas never lost hope of the United States.[7] Their objective was to both continue the fight against the Japanese and prepare for the return of the Americans. They were instrumental in helping the United States liberate the rest of the islands from the Japanese.

After the war, the American and Philippines governments officially recognized some of the units and individuals who had fought against the Japanese, which led to benefits for the veterans, but not all claims were upheld. There were 277 recognized guerrilla units out of over 1,000 claimed, and 260,715 individuals were recognized from nearly 1.3 million claims.[78] These benefits are only available to the guerrillas and veterans who have served for the Commonwealth, and don't include the brigand groups of the Huks and the Moros.[79] Resistance leaders Wendell Fertig, Russell W. Volckmann and Donald Blackburn would incorporate what they learned fighting with the Filipino guerrillas in establishing what would become the U.S. Special Forces.[80][81][82]

In 1944, only Filipino soldiers were denied from being given benefits by the GI Bill of Rights, which was supposed to give welfare to all those who have served in the United States Military irrespective of race, color or nationality. Over 66 countries were inducted into the bill but only the Philippines was left out, describing the Filipino soldiers as mere "Second Class Veterans".[83] Then in 1946, the Rescission Act was enacted to mandate some aid to Filipino veterans, but only to those who had disabilities or serious injuries.[84] The only benefit the United States could give at that time was the Immigrant Act, which made it easier for Filipinos who served in World War II to get American citizenship. It was not until 1996 that the veterans started seeking recognition from the United States. Representative Colleen Hanabusa submitted legislation to award Filipino Veterans with a Congressional Gold Medal, which became known as the Filipino Veterans of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act.[85] The Act was referred to the Committee on Financial Services and the Committee on House Administration.[86] The Philippine government has also enacted laws concerning the benefits of Filipino guerrillas.[87]

The World War II guerrilla movement in the Philippines has also garnered attention in Hollywood films such as Back to Bataan, Back Door to Hell, American Guerrilla in the Philippines, Cry of Battle and the more contemporary John Dahl film The Great Raid.[88][89][90] Filipino and Japanese films have also paid homage to the valor of the Filipino guerrillas during the occupation, such as Yamashita: The Tiger's Treasure, In the Bosom of the Enemy, Aishite Imasu 1941: Mahal Kita and the critically acclaimed Japanese film Fires on the Plain.[91][92][93] There have been various memorials and monuments erected to commemorate the actions of the Filipino guerrillas. Among such are the Filipino Heroes Memorial in Corregidor,[94] the Luis Taruc Memorial in San Luis, Pampanga, the bronze statue of a Filipino guerrilla in Corregidor, Balantang National Shrine in Jaro, Iloilo City to commemorate the 6th Military District that liberated the provinces of Panay, Romblon, and Guimaras,[95] and the NL Military Shrine and Park in La Union.[96] The Libingan ng mga Bayani (translated to Cemetery of the Heroes), which contains many Filipino national heroes, erected a special monument to pay respect to the numerous unnamed Filipino guerrillas who fought in the occupation.[97]

Notes

References

- Sinclair, II, Major Peter T. (December 1, 2011), "Men of Destiny: The American and Filipino Guerillas During the Japanese Occupation of the Philippines" (PDF), dtic.mil, School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College, archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2014, retrieved September 2, 2014

- Nypaver, Thomas R. (May 25, 2017). Command and Control of Guerrilla Groups in the Philippines, 1941-1945 (PDF) (Monograph). Command and General Staff College. Docket School of Advanced Military Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Tan, Chee-Beng (2012). Routledge Handbook of the Chinese Diaspora. Routledge. pp. 335–336.

- Hunt, Ray C.; Bernard Norling (2000). Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerrilla in the Philippines. University Press of Kentucky. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8131-0986-2. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Stein Ugelvik Larsen, Fascism Outside Europe, Columbia University Press, 2001, p. 785

- MacArthur, Douglas (1966). Reports of General MacArthur: Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area Volume 2, Part 1. JAPANESE DEMOBILIZATION BUREAUX RECORDS. p. 311. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Gordon L. Rottman (2002). World War 2 Pacific Island Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 287–289. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–2000. McFarland & Company. p. 566. ISBN 9780786412044.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (May 9, 2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. McFarland. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-7864-7470-7.

- Werner Gruhl, Imperial Japan's World War Two, 1931–1945 Transaction 2007 ISBN 978-0-7658-0352-8 p. 143-144

- Anne Sharp Wells (September 28, 2009). The A to Z of World War II: The War Against Japan. Scarecrow Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8108-7026-0.

"Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II". New Orleans, United States: The National WWII Museum. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

"AJR-27 War crimes: Japanese military during World War II". California Legislative Information. State of California. August 26, 1999. Retrieved July 23, 2019.WHEREAS, At the February 1945 "Battle of Manila," 100,000 men, women, and children were killed by Japanese armed forces in inhumane ways, adding to a total death toll that may have exceeded one million Filipinos during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, which began in December 1941 and ended in August 1945;

- "The Guerrilla War". American Experience. PBS. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- Jubair, Salah. "The Japanese Invasion". Maranao.Com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2010. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- "Have a bolo will travel". Asian Journal. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- "People & Events: Filipinos and the War". PBS.org. WGBH. 1999. Archived from the original on August 23, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

Rottman, Gordon (August 20, 2013). US Special Warfare Units in the Pacific Theater 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-1472805249. Retrieved September 2, 2014. - Lapham, Robert; Norling, Bernard (1996). Lapham's Raiders: Guerrillas in the Philippines, 1942–1945. University Press of Kentucky. p. 225. ISBN 978-0813126661. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- Rottman, Godron L. (2002). World War 2 Pacific island guide. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- Schmidt, Larry S. (1982). American Involvement in the Filipino Resistance Movement on Mindanao During the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945 (PDF) (Master of Military Art and Science thesis). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Prange, Gordon W., Goldstein, Donald, & Dillon, Katherine. The Pearl Harbor Papers (Brassey's, 2000), p.17ff; Google Books entry on Prange et al.

- For the Japanese designator of Oahu. Wilford, Timothy. "Decoding Pearl Harbor", in The Northern Mariner, XII, #1 (January 2002), p.32fn81.

- Fukudome, Shigeru, "Hawaii Operation". United States Naval Institute, Proceedings, 81 (December 1955), pp.1315–1331

- Morison, Samuel Eliot The Liberation of the Philippines: Luzon, Mindanao, the Visayas 1944–1945 (History of United States Naval Operations in World War II) Castle Books (2001). pp. 101, 120, 250. ISBN 978-0785813149

- Fukudome, Shigeru. Shikan: Shinjuwan Kogeki (Tokyo, 1955), p. 150.

- "Chapter VI: Conquest of the Philippines". Reports of General MacArthur: Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area. Vol. II – Part I. Department of the Army. 1994 [1950]. LCCN 66060007. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- Bataan Death March. Britannica Encyclopedia Online

- Lansford, Tom (2001). "Bataan Death March". In Sandler, Stanley (ed.). World War II in the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0-8153-1883-5.

- Manahan, Manuel P. (1987). Reader's Digest November 1987 issue: Biographical Tribute to Ramon Magsaysay. pp. 17–23.

- "Philippine Resistance: Refusal to Surrender". Asia at War. October 17, 2009. History Channel Asia.

- Mojica, Proculo (1960). Terry's Hunters: The True Story of the Hunters ROTC Guerillas.

- "Remember Los Banos 1945". Los Banos Liberation Memorial Scholarship Foundation, Inc. 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- McCoy, Alfred W. (1999). Closer than brothers: manhood at the Philippine Military Academy. Yale University Press. pp. 167–170. ISBN 978-0-300-07765-0.

- Paul Morrow (January 16, 2009). "Maharlika and the ancient class system". Pilipino Express. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- Quimpo, Nathan Gilbert. Filipino nationalism is a contradiction in terms, Colonial Name, Colonial Mentality and Ethnocentrism, Part One of Four, "Kasama" Vol. 17 No. 3 / July–August–September 2003 / Solidarity Philippines Australia Network, cpcabrisbance.org

- Robles, Raissa (May 17, 2011). "Eminent Filipino war historian slams Marcos burial as a "hero"". Raissa Robles: Inside Politics and Beyond.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Joseph A. Reaves (September 29, 1989). "Marcos Was More Than Just Another Deposed Dictator". Chicago Tribune."US Department of Defense official database of Distinguished Service Cross recipients".

- Robert Lapham, Bernard Norling (April 23, 2014). Lapham's Raiders: Guerrillas in the Philippines, 1942–1945. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813145709.

- Hogan, David W. Jr. (1992). "Chapter 4: Special Operations in the Pacific". U.S. Army Special Operations in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. pp. 64–96. ISBN 9781410216908. OCLC 316829618. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- Cannon, M. Hamlin (1954). War in the Pacific: Leyte, Return to the Philippines. Government Printing Office. p. 19. ASIN B000JL8WEG. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- Eisner, Peter (September 2017). "Without Chick Parsons, General MacArthur May Never Have Made His Famed Return to the Philippines". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- "Guerrillas in the Philippines". West-Point.Org. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

In May 1943 The Philippine Regional Section (PRS) was created as part of AIB and given the task of coordinating all activities in the Philippines

Bigelow, Michael E. (July 26, 2016). "Allied Intelligence Bureau plays role in World War II". United States Army. Retrieved July 26, 2019. - "Narwhal II (SC-1)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command.

"Nautilus III (SS-168)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. - Gordon L. Rottman (August 20, 2013). US Special Warfare Units in the Pacific Theater 1941–45: Scouts, Raiders, Rangers and Reconnaissance Units. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 39–43. ISBN 978-1-4728-0546-1.

Fabros, Alex S. Jr., ed. (October 5, 1998). "Bahalan Na News Letter 1st Reconnaissance Battalion" (PDF). The Filipino American Experience Research Project. Retrieved July 26, 2019 – via Salinas Public Library.

Bielakowski, Alexander M. (2013). Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military: A-L. ABC-CLIO. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-1-59884-427-6. - Sides, Hampton (2001). Ghost Soldiers: The Forgotten Epic Story of World War II's Most Dramatic Mission. pp. 291–293. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-49564-1

- Hunt, Ray C.; Norling, Bernard (2000). Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerrilla in the Philippines. University of Kentucky Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0813127552. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- Ceniza, Christian. "10 Chilling Photos That Show The Atrocities Of War In The Philippines". Ten Minutes. February 2, 2015

- "WORLD WAR II AND HUK EXPANSION". History.Army. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- Vaflor, Marc (September 10, 2015). "This Unsung WWII Hero Will Inspire You To Be A Better Filipino". Filipiknow.

- Mari-An C., Santos. "REVIEW: "Bintao" recalls the struggles of revolutionary leader Wenceslao Vinzons". PEP. February 15, 2008

- Saulo, Alfredo B., Communism in the Philippines: an Introduction, Enlarged Ed., Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1990, p. 31

- Greenberg, Major Lawrence M. (1986). "Chapter 2: World War II and Huk Expansion". The Hukbalahap Insurrection. U.S. Government Printing Office. LCCN 86600597. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- Lembke, Andrew E. (2013). Lansdale, Magsaysay, America, and the Philippines: A Case Study of Limited Intervention Counterinsurgency (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780988583764.

The Huks are alleged to have killed 25,000 people in the Philippines during the occupation; of that number only 5,000 were Japanese.

- "How Chinese guerrillas fought for Philippine freedom". ABS-CBN Corporation. February 19, 2015. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022.

- "World War II".

- "How Chinese guerrillas fought for Philippine freedom". ABS-CBN News. February 2, 2015

- The Lewiston Daily Sun – Nov 3, 1944

- "Philippine Resistance: Refusal to Surrender". Tivarati Entertainment. Archived from the original on December 29, 2021. October 13, 2009

- Augusto V. de Viana. "THE CAPTURE OF THE KOGA PAPERS AND ITS EFFECT ON THE PLAN TO RETAKE THE PHILIPPINES IN 1944" (PDF). Micronesian: Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "How Cebuano Fishermen Helped Defeat the Japanese in World War II". Filipiknow. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- The "Z Plan" Story Japan's 1944 Naval Battle Strategy Drifts into U.S. Hands, Greg Bradsher, Prologue Magazine, Fall 2005, Vol. 37, No. 3

- Prefer, N.N., 2012, Leyte 1944, Havertown: Casemate Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9781612001555

- Felias, Remedios, The Hidden Battle of Leyte – the Picture Diary of a Girl Taken By the Japanese Military, Bucong Bucong (1999), pp. 12–18. Asin: B000JL8WEG

- Lofgren, Stephen (1996). Southern Philippines. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0160481406. p. 98

- "Tiring Landing Field, located in Cabatuan, Iloilo". Cabatuan.com Center for Cabatuan Studies, IloiloAirport.com.

- Barreveld, Dick J. (2015). Cushing's Coup: The True Story of How Lt. Col. James Cushing and his Filipino Guerrillas Captured Japan's Plan Z. Philadelphia: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-612-00308-5.

- Gross, p. 178.

- Arnold 2011, p. 271.

- Keats 1990, pp. 354–355.

- Schmidt (1982), p. 165.

- "Terror in Jolo". Time Magazine. December 1, 1941. Archived from the original on November 22, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- "Maniacal Moros". Black Belt. Active Interest Media Inc. 26 (12): 56. December 1988. ISSN 0277-3066.

- "80 Japanese Troop Ships Are Sighted Off Luzon" 1941, p. 7.

- First National Scientific Workshop on Muslim Autonomy, January 14–18, 1987, p. 19.

- Zincke & Mills 2002, p. 47.

- A. P. 1942, p. 24.

- Vaflor, Marc. "The 10 Most Fearsome One-Man Armies in Philippine History". Filipiknow. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- MacArthur, Douglas (1964). Reminiscences of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Annapolis: Bluejacket Books. ISBN 1-55750-483-0. p.103

- Caraccilo, Dominic J. (2005). Surviving Bataan And Beyond: Colonel Irvin Alexander's Odyssey As a Japanese Prisoner Of War. Stackpole Books. pp. 287. ISBN 978-0-8117-3248-2.

- Schmidt (1984) p. 5.

- Schmidt (1984) p.6

- Keats, John. (1965). They Fought Alone. Pocket Books, Inc. OCLC 251563972 p.445

- Bernay A. (2002). "Shuttle Camp Wendell Fertig ." (PDF). In The Tribble Times. page 14. Retrieved September 7, 2009. (An interview with Fertig's daughter: Patricia Hudson, of Coeur D Alene, Idaho.) p.14

- "The History of PsyWar after WWII and Its Relationship to Special Forces". Timyoho. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- Nakano, Satoshi (June 2004). "The Filipino World War II veterans equity movement and the Filipino American community" (PDF). Seventh Annual International Philippine Studies. Center for Pacific And American Studies: 53–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2015. Alt URL

- Tiongson, Antonio T.; Gutierrez, Edgardo V.; Gutierrez, Ricardo V. (2006). Positively No Filipinos Allowed: Building Communities and Discourse. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-592-13123-5.

- Richard Simon (January 30, 2013). "Philippine vets still fighting their battle over WWII". Stars and Stripes. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- "Committees: H.R.111 [113th]". Congress.gov. Library of Congress. January 3, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- "Philippine government pensions for war veterans". Official Gazette. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

- Richard Jewell and Vernon Harbin, The RKO Story. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House, 1982. p. 204

- Barber, Mike (August 25, 2005). "Leader of WWII's "Great Raid" looks back on real-life POW rescue". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Bulkley, Robert J.; Kennedy, John F.; Eller, Ernest MacNeill (2003). At Close Quarters: PT Boats in the United States Navy, Naval Institute Press, p. 24.

- "51 Countries In Race For Oscar". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. November 19, 2001. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.

- Yamashita: The Tiger's Treasure 2001 directed by Chito S. Rono, retrieved March 19, 2012

- "JAPANESE FILM CITED; ' Nobi,' War Movie, Wins First Prize at Locarno Festival". The New York Times. July 31, 1961. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- Gonzalez, Vernadette V. (2013). Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawai'i and the Philippines. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-822-39594-2.

- Villalón, Augusti (2007). Living Landscapes and Cultural Landmarks: World Heritage Sites in the Philippines. ArtPost Asia Books. ISBN 978-9-7193-1708-1.

- Fllipino government (2007). "Memorials for Fllipino veterans". Official Gazette. Fllipino national Press. 95 (32): 1981. ISSN 0115-0421.

- Laputt, Juny. "Republic Memorial Cemetery at Fort McKinley". Corregidor Island. Retrieved July 26, 2015.

Further reading

- "U.S. Army Recognition Program of Philippine Guerrillas" (PDF). Headquarters, Philippine Command, United States Army. National Archives and Records Administration. 1948. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- General MacArthur's General Staff (June 20, 2006) [1966]. "CHAPTER X; GUERRILLA ACTIVITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES". Reports of General MacArthur. United States Army. pp. 295–326. LCCN 66-60005. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Morningstar, James K. (2021). War and Resistance in the Philippines, 1942-1944. Naval Institute Press.

- Schmidt, Major Larry S. (1982). American Involvement in the Filipino Resistance Movement on Mindanao During the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014.

- Villanueva, James A. (2022). Awaiting MacArthur's Return: World War II Guerrilla Resistance against the Japanese in the Philippines. University Press of Kansas.

- Hogan, Jr., David W. (1992) "Chapter 4: Special Operations in the Pacific" in U.S. Army Special Operations in World War II, CMH Publication 70-42, Center of Military History, Department of the Army.

External links

- "Alphabetical List of Guerrilla Units and Their File Codes in the Guerrilla Unit Recognition Files". Philippine Archives Collection. National Archive. August 15, 2016.

- "Roderick Hall Collection: On World War II in the Philippines". Filipinas heritage Library. Ayala Foundation.